Construction-In-Progress

Biographies of Prominent

Utah Deaf Men

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Published in 2012

Updated in 2021

Updated in 2023

Published in 2012

Updated in 2021

Updated in 2023

Acknowledgement

I want to express my sincere gratitude to Valerie G. Kinney for her essential support in proofreading this document and interviewing sources close to prominent individuals for more biographical details.

I am deeply thankful to Anne Leahy for her generosity in assisting and contributing to the hard-to-find archive collections of specific individuals.

I would like to show my appreciation and thanks to Helen Salas-McCarty for donating her time to proofread and edit the documents.

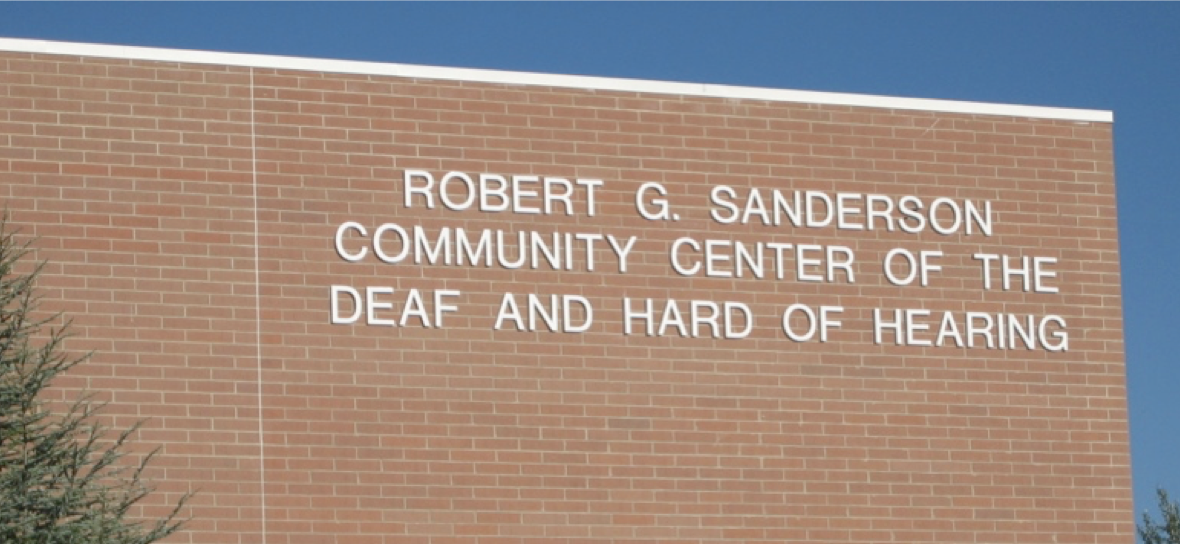

I also want to thank Dr. Robert G. Sanderson (via Valerie G. Kinney), Kenneth L. Kinner, and Doug Stringham for recommending the names of prominent individuals.

I am deeply thankful to Anne Leahy for her generosity in assisting and contributing to the hard-to-find archive collections of specific individuals.

I would like to show my appreciation and thanks to Helen Salas-McCarty for donating her time to proofread and edit the documents.

I also want to thank Dr. Robert G. Sanderson (via Valerie G. Kinney), Kenneth L. Kinner, and Doug Stringham for recommending the names of prominent individuals.

I would also like to express my gratitude to Anne Leahy, Doug Stringham, and David Samuelson for their valuable direction and guidance. Moreover, I extend special thanks to those who provided important biographical details about the subjects of these biographies.

I want to express my gratitude to Eleanor McCowan for suggesting that I take on the Utah Deaf History project. Without her suggestion, none of this would have been possible.

I also want to thank my colleague, James Fenton, for recommending that I include a summary of each biography.

I am incredibly appreciative of the support and patience of my spouse, Duane Kinner, and my children, Joshua and Danielle, throughout the completion of this project. The "Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Women" webpage would not have been possible without their support. Thank you!

I want to express my gratitude to Eleanor McCowan for suggesting that I take on the Utah Deaf History project. Without her suggestion, none of this would have been possible.

I also want to thank my colleague, James Fenton, for recommending that I include a summary of each biography.

I am incredibly appreciative of the support and patience of my spouse, Duane Kinner, and my children, Joshua and Danielle, throughout the completion of this project. The "Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Women" webpage would not have been possible without their support. Thank you!

Why Does The Biographies

of Prominent Utah Deaf Men Matter?

of Prominent Utah Deaf Men Matter?

"The Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Men" is an invaluable resource for the ASL community, particularly for the younger Deaf generation in Utah. It provides insight into the lives of local Deaf role models, helping future generations learn from their leadership traits. By studying these biographies, individuals can effectively advocate for causes and become more literate, educated, prosperous, and productive citizens.

I admire the Utah Deaf individuals featured on this webpage for their unwavering dedication to improving the lives of the Deaf community in Utah. I hope their biographies encourage readers to follow in their extraordinary footsteps. Finally, I appreciate these leaders' selfless dedication and contributions to our Utah Deaf community.

Have fun while reading!

Jodi Becker Kinner

I admire the Utah Deaf individuals featured on this webpage for their unwavering dedication to improving the lives of the Deaf community in Utah. I hope their biographies encourage readers to follow in their extraordinary footsteps. Finally, I appreciate these leaders' selfless dedication and contributions to our Utah Deaf community.

Have fun while reading!

Jodi Becker Kinner

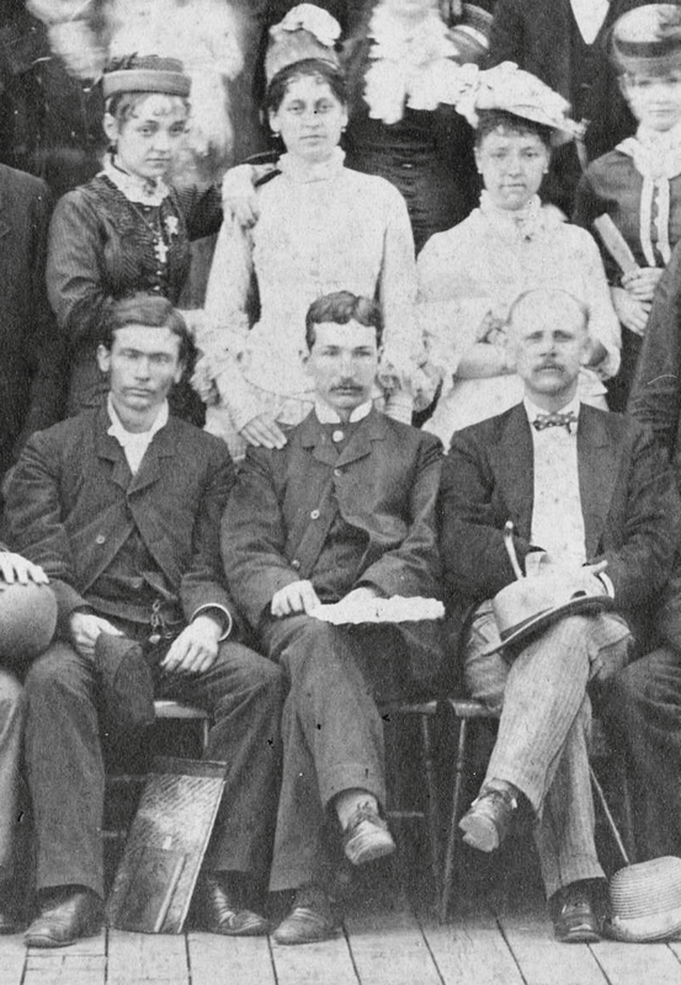

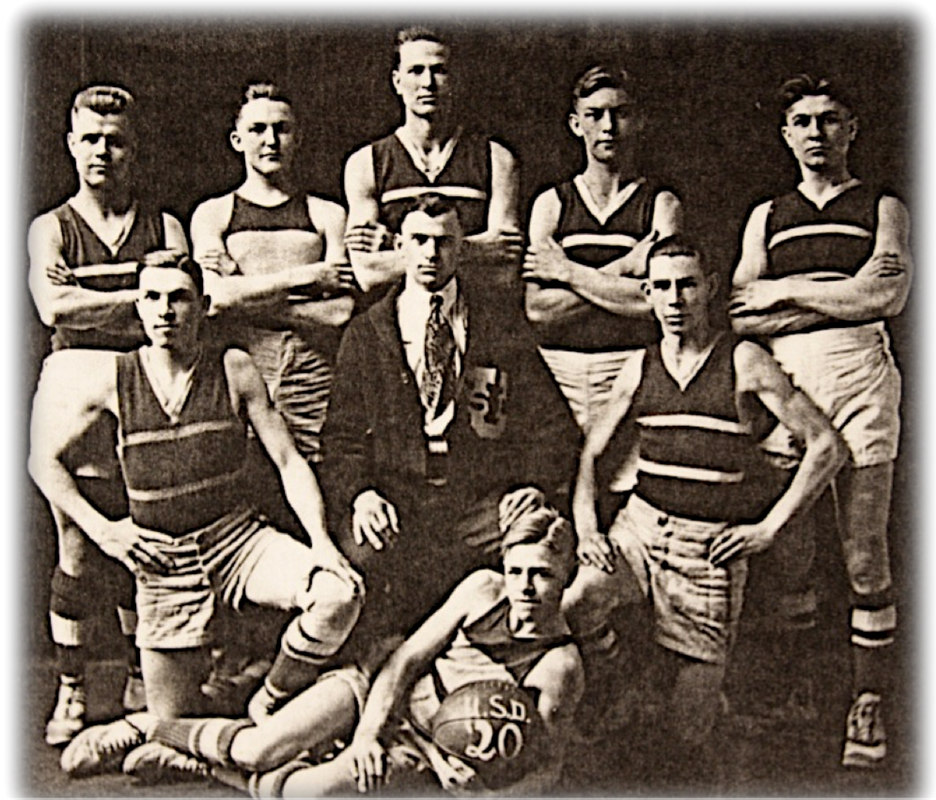

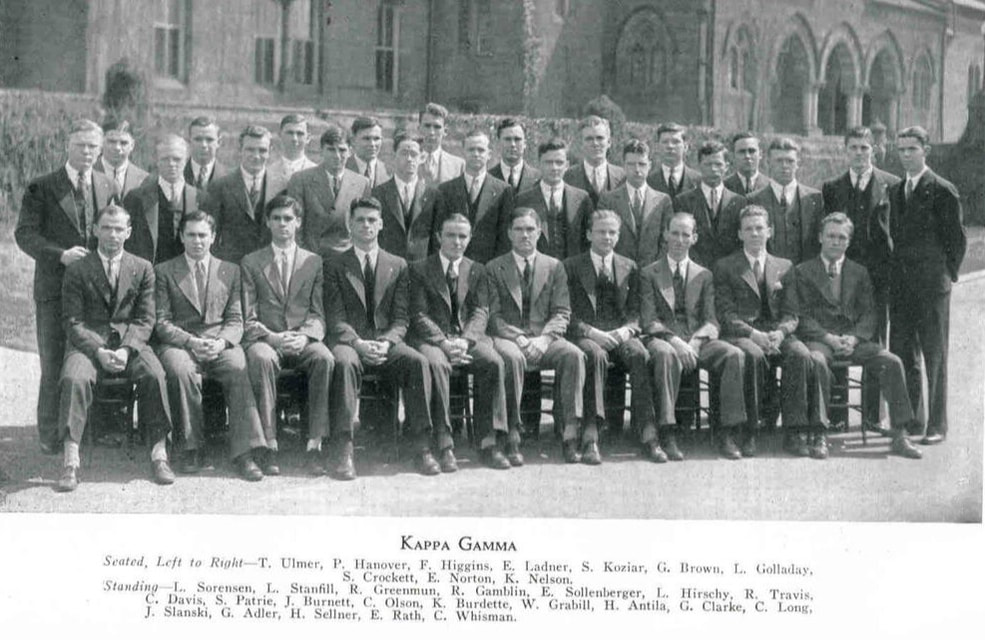

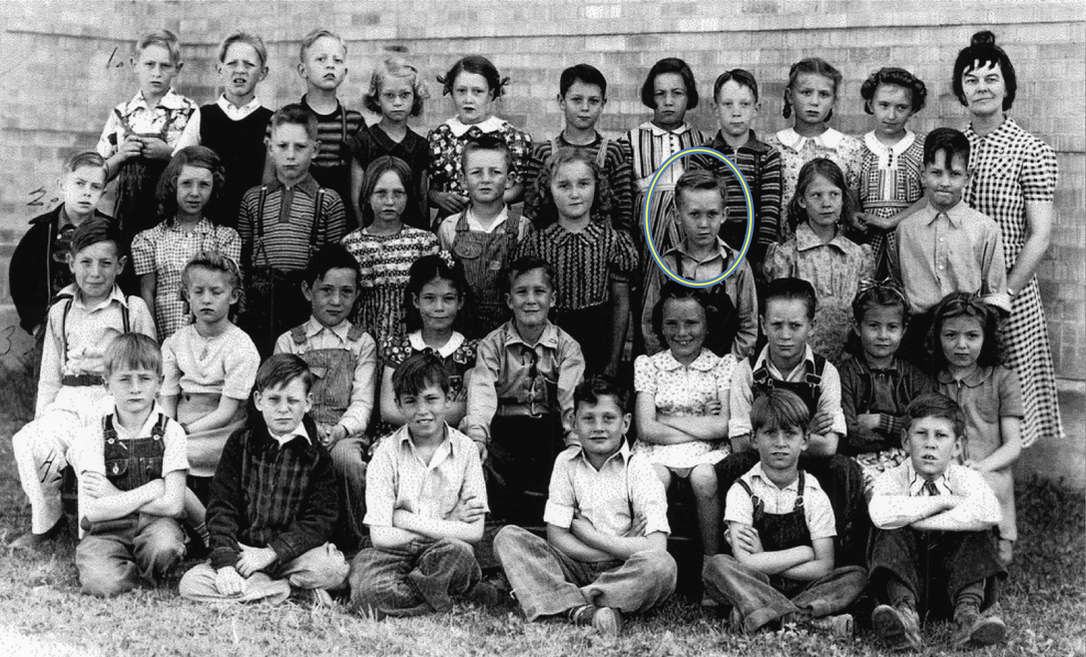

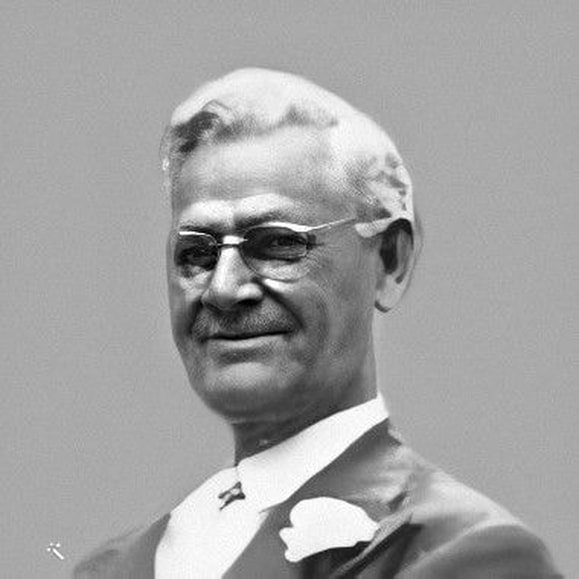

Students of Utah School for the Deaf, 1928-1930. Back L-R: Wayne Stewart, William Woodward, Alton Fisher, John (Jack) White, Joseph Burnett, possible Leon Edwards, Arvel Christensen, Virgil Greenwood, ____

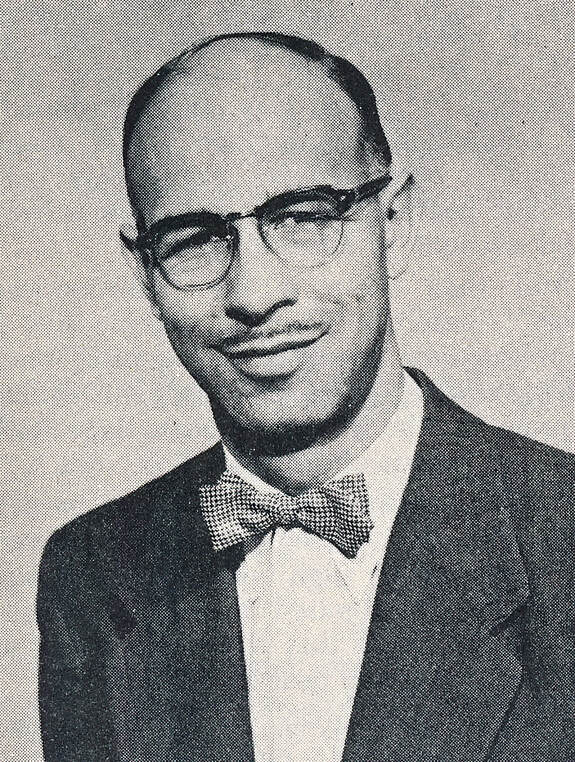

Front L-R: J. Sherwood Messerly, Rodney Walker, Melvin Penman, Wesley Perry, Verl Throup, _____

“The price of success is hard work, dedication to the job at hand, and the determination that whether we win or lose, we have applied the best of ourselves to the task at hand.”

~Vince Lombardi~

~Vince Lombardi~

Note

Some biographies included religion, specifically The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has had a significant and lasting impact on Utah's history. This influence also extends to the Utah Deaf community, making it an important part of our collective heritage.

The biographies will be valuable for the individuals' families, aiding in preserving history and exploring their lineage. Additionally, these biographies will help preserve the life stories of these individuals for future generations to appreciate and remember.

To avoid confusion, I will refer to the organization as the Utah Association of the Deaf on this webpage, as they used the word "of" in their name from 1909 to 1962. The organization changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963 and then reversed it in 2012 to become the Utah Association of the Deaf.

The biographies will be valuable for the individuals' families, aiding in preserving history and exploring their lineage. Additionally, these biographies will help preserve the life stories of these individuals for future generations to appreciate and remember.

To avoid confusion, I will refer to the organization as the Utah Association of the Deaf on this webpage, as they used the word "of" in their name from 1909 to 1962. The organization changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963 and then reversed it in 2012 to become the Utah Association of the Deaf.

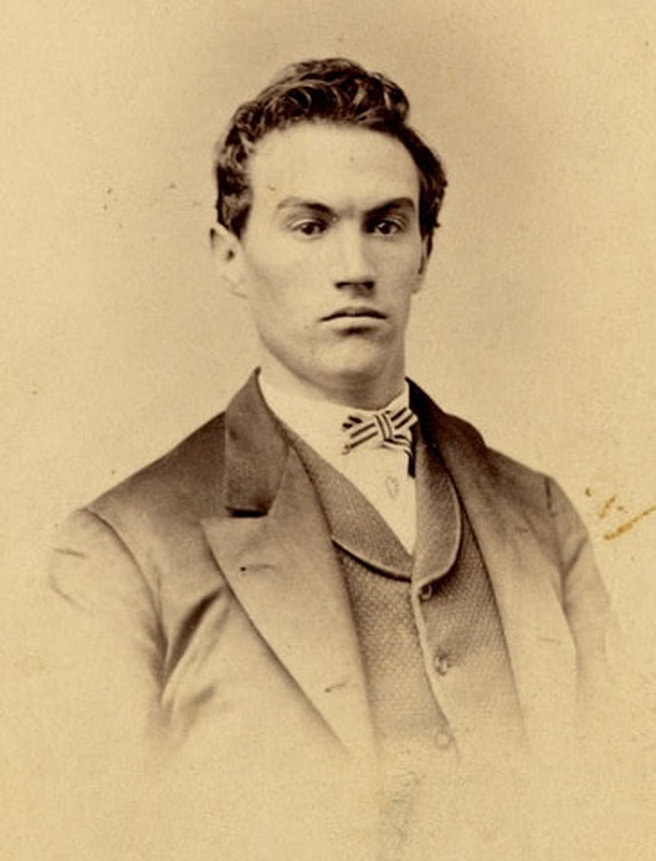

Laron Pratt,

the Utah's first Deaf leader in the 1800s

the Utah's first Deaf leader in the 1800s

On January 10, 1892, Laron Pratt was appointed assistant superintendent of the Deaf Mute Sunday School in Salt Lake City's 19th Ward. He eventually became a stake Sunday School missionary and started giving talks at local and general church gatherings and signing hymns with his daughter as an interpreter. Laron is believed to have been the first and only Deaf leader in Utah of the newly formed Deaf community in the 1800s before establishing the Utah School for the Deaf in 1880. He has made significant contributions to the Utah Deaf community and Deaf members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Laron Pratt was born in Florence, Douglas County, Nebraska, on April 14, 1847. He was the son of the late Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Apostle Orson Pratt and his first wife (of 10), Sarah Marinda Bates. Plural marriage was common at the time.

Laron was three years old when he developed a high fever and went deaf. He had some spoken language skills as an adult. He was also fluent in sign language. He could also read lips and speak well (The Utah Eagle, March 1917).

Laron arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with his father's Pioneer Company from Winter Quarters on October 4, 1851, at the age of four (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011). Apostle Pratt was a member of President Brigham Young's pioneering company, the "Vanguard Company.

Laron relocated to St. George with his family ten years later, in October 1861. In August 1864, he went to Salt Lake City, where he became the first Deaf leader of the newly formed Deaf community (Doug Stringham, personal communication, June 2, 2011; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Like other Deaf people in Utah between 1850 and 1880, they were most likely educated or tutored at home by their parents (Doug Stringham, personal communication, June 2, 2011). Laron was one of them. He authored and published a few articles for the Deseret News as a well-educated man.

He started working for the Deseret News in 1862 and stayed for nearly 50 years (Deseret News, August 24, 1908). He rose through the ranks to become a well-known compositor (typesetter) (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

On June 7, 1876, while working for the Deseret News, Laron's essay "The English of Deaf Mutes" was reprinted from an unknown newspaper exchange source (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

According to the 1880 census, Laron's household included a hearing wife, Ethelwynne Clarissa Brown, and six children. He hired a young Swiss woman to do housekeeping. He married Ethelwynne on June 27, 1869, in Salt Lake City, Utah. Their children were Laron Jr., Maude Eudora, Ethelwynne Clarissa, Sarah Marinda, Hermie Estelle, and Pemelia Pearl. Laron's eldest son, Laron Jr., died at the age of 15 in 1885 (Deseret News, November 18, 1885).

Laron, at 37, had two essays published in the Deseret Evening News. On April 16, 1884, he submitted his first article, "Deaf Mutes: A Good Word on Behalf of the Unfortunates." It was printed on page 211, seven days later. Loran praised the legislature's provision for the education of Deaf children in Utah Territory and provided an insider's view of Deaf culture for a hearing audience (Pratt, Deseret Evening News, April 16, 1884; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

On June 22, 1884, he authored his second article, "A Kind Word in Behalf of Deaf Mutes," which was submitted and published in the Deseret Evening News, p. 379. He quoted Marquis L. Brock from a lecture at the American Instructors of the Deaf and Dumb convention in his essay: "The whole world of sound is a sealed book [to deaf people]." Laron also advocated for religious and moral education. This suggests that he subscribed to the American Annals of the Deaf, which published his paper (Pratt, Deseret News, June 22, 1884; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Laron was three years old when he developed a high fever and went deaf. He had some spoken language skills as an adult. He was also fluent in sign language. He could also read lips and speak well (The Utah Eagle, March 1917).

Laron arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with his father's Pioneer Company from Winter Quarters on October 4, 1851, at the age of four (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011). Apostle Pratt was a member of President Brigham Young's pioneering company, the "Vanguard Company.

Laron relocated to St. George with his family ten years later, in October 1861. In August 1864, he went to Salt Lake City, where he became the first Deaf leader of the newly formed Deaf community (Doug Stringham, personal communication, June 2, 2011; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Like other Deaf people in Utah between 1850 and 1880, they were most likely educated or tutored at home by their parents (Doug Stringham, personal communication, June 2, 2011). Laron was one of them. He authored and published a few articles for the Deseret News as a well-educated man.

He started working for the Deseret News in 1862 and stayed for nearly 50 years (Deseret News, August 24, 1908). He rose through the ranks to become a well-known compositor (typesetter) (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

On June 7, 1876, while working for the Deseret News, Laron's essay "The English of Deaf Mutes" was reprinted from an unknown newspaper exchange source (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

According to the 1880 census, Laron's household included a hearing wife, Ethelwynne Clarissa Brown, and six children. He hired a young Swiss woman to do housekeeping. He married Ethelwynne on June 27, 1869, in Salt Lake City, Utah. Their children were Laron Jr., Maude Eudora, Ethelwynne Clarissa, Sarah Marinda, Hermie Estelle, and Pemelia Pearl. Laron's eldest son, Laron Jr., died at the age of 15 in 1885 (Deseret News, November 18, 1885).

Laron, at 37, had two essays published in the Deseret Evening News. On April 16, 1884, he submitted his first article, "Deaf Mutes: A Good Word on Behalf of the Unfortunates." It was printed on page 211, seven days later. Loran praised the legislature's provision for the education of Deaf children in Utah Territory and provided an insider's view of Deaf culture for a hearing audience (Pratt, Deseret Evening News, April 16, 1884; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

On June 22, 1884, he authored his second article, "A Kind Word in Behalf of Deaf Mutes," which was submitted and published in the Deseret Evening News, p. 379. He quoted Marquis L. Brock from a lecture at the American Instructors of the Deaf and Dumb convention in his essay: "The whole world of sound is a sealed book [to deaf people]." Laron also advocated for religious and moral education. This suggests that he subscribed to the American Annals of the Deaf, which published his paper (Pratt, Deseret News, June 22, 1884; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Laron personally called President Wilford W. Woodruff of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on January 24, 1881, to express a desire to teach the Deaf (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011). Eleven years later, on January 10, 1892, Laron established the Deaf Mute Sunday School in Salt Lake City's 19th Ward and was called as assistant superintendent. He became a stake Sunday School missionary, traveling to local and general church meetings to give talks and sign hymns with his daughter as an interpreter (The Daily Enquirer, February 11, 1892; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Following the relocation of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1896, the Deaf Mute Sunday School was relocated to the Ogden 4th Ward. He began his weekly train trips to continue serving as a teacher and assistant superintendent until he was appointed as an honorary member of the superintendency on October 7, 1907, "as a reward for his faithful service" (Desert News, November 21, 1896; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Laron was featured in Orson F. Whitney's History of Utah, p. 29, in 1904, as one of the seventeen most prominent of Orson Pratt's forty-five children (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Laron passed away in Salt Lake City, Utah, on August 22, 1908. His dedicated friends organized his funeral in the Seventeenth Ward chapel, packed with relatives and friends. Students from the Utah School for the Deaf came to pay their respects at the funeral. His former colleagues from the Deseret News, where he had worked as a printer, were also present. Many florals were on exhibit, expressing the community's esteem and affection for Elder Laron Pratt (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Following the relocation of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1896, the Deaf Mute Sunday School was relocated to the Ogden 4th Ward. He began his weekly train trips to continue serving as a teacher and assistant superintendent until he was appointed as an honorary member of the superintendency on October 7, 1907, "as a reward for his faithful service" (Desert News, November 21, 1896; Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Laron was featured in Orson F. Whitney's History of Utah, p. 29, in 1904, as one of the seventeen most prominent of Orson Pratt's forty-five children (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Laron passed away in Salt Lake City, Utah, on August 22, 1908. His dedicated friends organized his funeral in the Seventeenth Ward chapel, packed with relatives and friends. Students from the Utah School for the Deaf came to pay their respects at the funeral. His former colleagues from the Deseret News, where he had worked as a printer, were also present. Many florals were on exhibit, expressing the community's esteem and affection for Elder Laron Pratt (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Laron's memorial service featured three speakers. Elder J.M. Sjodahl, an editor for the Deseret News, was the first to speak. He highlighted Laron's noble and honest life and his condolences to Loran's family (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Elder John Henry Smith, who had known Laron since his youth, remarked on his heroic life and how he faced "almost insurmountable obstacles that made a success of the great battle of life." John also praised Laron for raising his honored family, remaining faithful, and earning the respect of all who knew him. Laron's life, according to John, was "truly an exemplary one, and he was a worthy son of his distinguished father, Orson Pratt, one of the earliest standard bearers of Mormonism and a Utah pioneer" (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Lastly, Elder Fred W. Chambers, superintendent of the Deaf Mute Sunday school, Ogden, spoke feelingly of the devotion of Elder Pratt [who lived in Salt Lake City], who went to Ogden every Sabbath for nearly nine years to teach Deaf children the gospel (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Elder Fred W. Chambers, superintendent of the Deaf Mute Sunday school in Ogden, talked movingly of Elder Pratt [who lived in Salt Lake City], who traveled to Ogden every Sunday for over nine years to teach Deaf children the gospel (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Elder John Henry Smith, who had known Laron since his youth, remarked on his heroic life and how he faced "almost insurmountable obstacles that made a success of the great battle of life." John also praised Laron for raising his honored family, remaining faithful, and earning the respect of all who knew him. Laron's life, according to John, was "truly an exemplary one, and he was a worthy son of his distinguished father, Orson Pratt, one of the earliest standard bearers of Mormonism and a Utah pioneer" (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Lastly, Elder Fred W. Chambers, superintendent of the Deaf Mute Sunday school, Ogden, spoke feelingly of the devotion of Elder Pratt [who lived in Salt Lake City], who went to Ogden every Sabbath for nearly nine years to teach Deaf children the gospel (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Elder Fred W. Chambers, superintendent of the Deaf Mute Sunday school in Ogden, talked movingly of Elder Pratt [who lived in Salt Lake City], who traveled to Ogden every Sunday for over nine years to teach Deaf children the gospel (Deseret News, August 24, 1908).

Notes

Anne Leahy, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, June 3, 2011.

Doug Stringham, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, June 2, 2011.

Doug Stringham, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, June 2, 2011.

References

"A Brief History of the Sunday School for the Deaf." The Utah Eagle, Vol. 28, No. 6, March 1917.

"A Sunday School Organized for the Deaf Mutes." The Daily Enquirer, February 11, 1892. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Aug. 2006. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_organization.html

"Bereaved." Deseret News, November 18, 1885. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_son_dies.html

“For Blind, Deaf, and Dumb.” Deseret News, November 21, 1896. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Aug. 2006. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_organization.html

“Funeral of Laron Pratt: Veteran Printer Laid to Rest After Impressive Service

Attended by Host of Devoted Friends.” Deseret News, August 24, 1908. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Aug. 2006. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_obituary.html

Pratt, Laron. "Deaf Mutes: A good word in behalf of the unfortunates." Deseret News, April 16, 1884. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Apr. 2006 http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_good_word.html

Pratt, Larson. “A Kind Word in Behalf of Deaf Mutes.” Deseret News, June 22, 1884. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Apr. 2006. (Online). Available HTTP: http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_kind_word.html

"A Sunday School Organized for the Deaf Mutes." The Daily Enquirer, February 11, 1892. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Aug. 2006. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_organization.html

"Bereaved." Deseret News, November 18, 1885. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_son_dies.html

“For Blind, Deaf, and Dumb.” Deseret News, November 21, 1896. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Aug. 2006. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_organization.html

“Funeral of Laron Pratt: Veteran Printer Laid to Rest After Impressive Service

Attended by Host of Devoted Friends.” Deseret News, August 24, 1908. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Aug. 2006. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_obituary.html

Pratt, Laron. "Deaf Mutes: A good word in behalf of the unfortunates." Deseret News, April 16, 1884. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Apr. 2006 http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_good_word.html

Pratt, Larson. “A Kind Word in Behalf of Deaf Mutes.” Deseret News, June 22, 1884. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Apr. 2006. (Online). Available HTTP: http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_kind_word.html

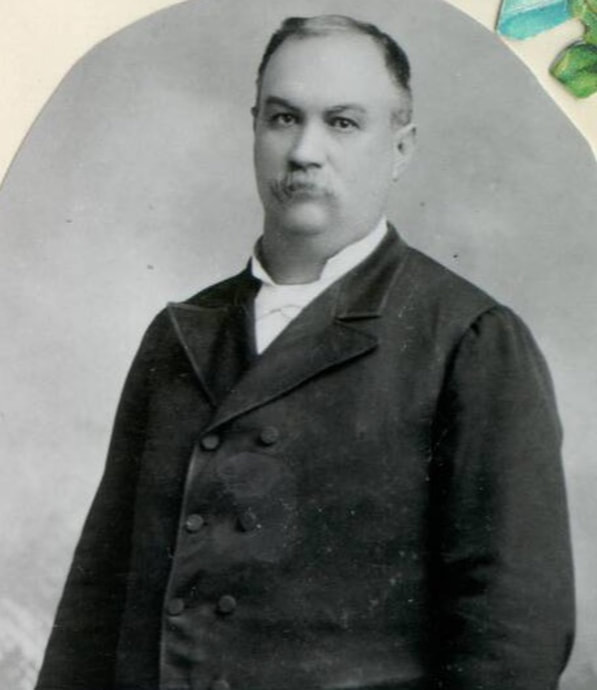

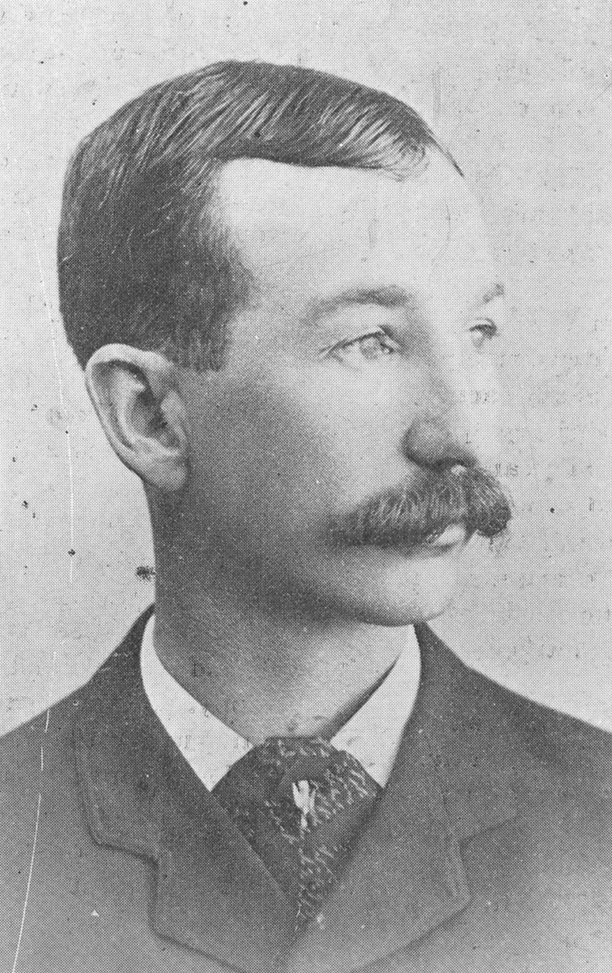

Henry C. White, Outspoken Leader

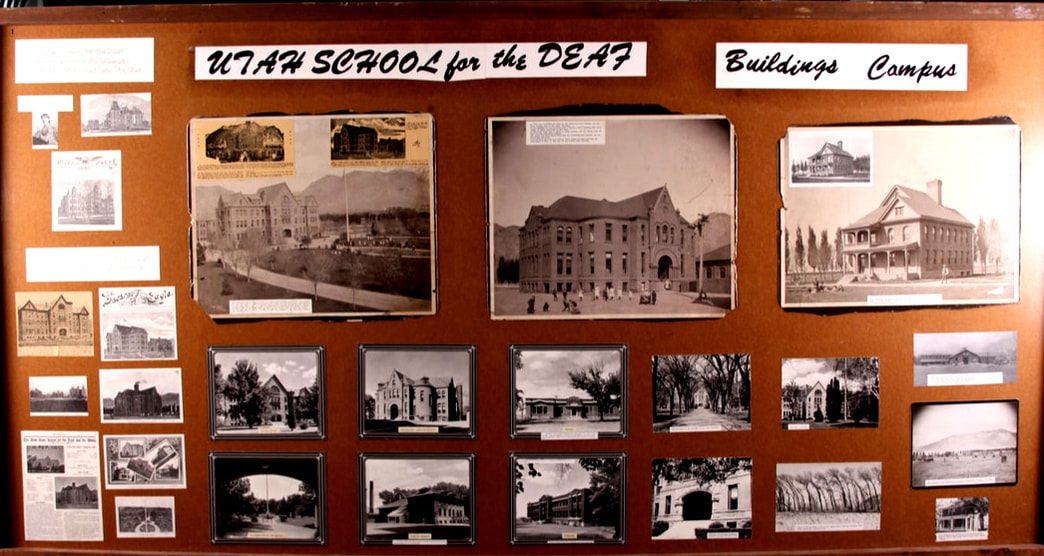

Henry C. White was named principal of the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) in Salt Lake City, Utah in 1884 by Dr. John R. Park, president of the University of Utah, following the recommendation of Dr. Edward M. Gallaudet, president of Gallaudet College. He remained at USD until 1890, serving as a teacher, principal, and headmaster. Henry established the Arizona School for the Deaf at the University of Arizona in 1911, similar to the Utah School for the Deaf. He graduated from Gallaudet College in 1880 and was one of the first attendees at the first convention of the National Association of the Deaf in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the same year.

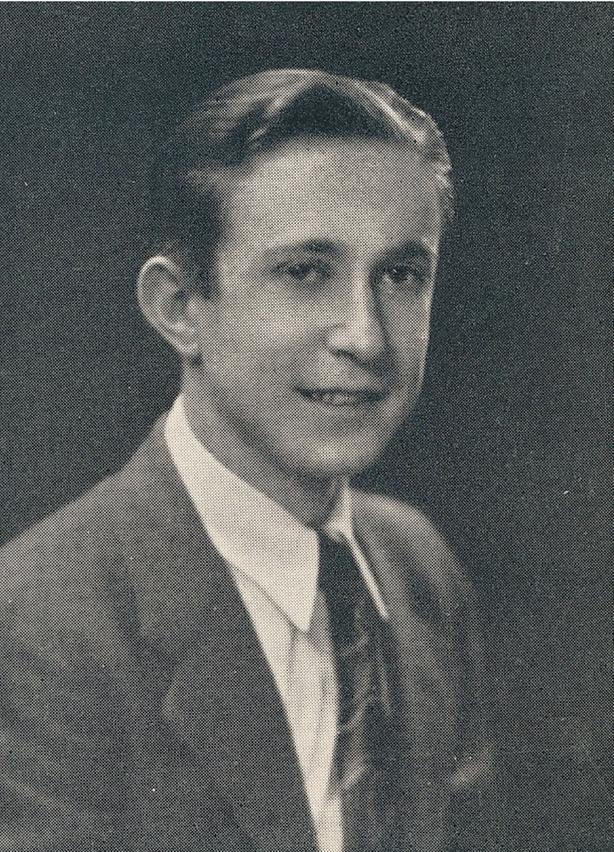

Henry C. White was born hearing on November 9, 1856 in Roxbury, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts. He lost his hearing at age four from scarlet fever (Census of Henry C. White). He was raised in Roxbury, Massachusetts. He first attended the Horace Mann Day School for the Deaf in Boston. In 1866, when he was nine years old, he went to the Hartford School for the Deaf as a student (The Utah Eagle, February 1922). After graduating from Hartford in 1880, he went to the Columbia Institute for the Deaf and Dumb (later renamed Gallaudet University) in Washington, D.C., where he got a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1880 (Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866–1957; The Utah Eagle, February 1922). The same year, he attended the National Association of the Deaf's first Cincinnati convention (Gannon, 1981).

Soon after he graduated, Henry became the manager of a home for older Deaf people in Allston, Massachusetts (Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866–1957). Then, on the advice of Dr. Edward M. Gallaudet, president of Gallaudet College, Dr. John R. Park, president of the University of Utah, made Henry the first principal of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1884. The Legislature created the school as a part of the state university because John Beck and William Wood, both parents of Deaf children, pushed for it. It opened in a room in the University building on August 26, 1884 (The Utah Eagle, February 1922). Henry stayed at USD as a teacher, principal, and head teacher until 1890. Although Henry C. White did not found the Utah School for the Deaf, he is credited with leading and maintaining it, which still exists today, as a leader and administrator despite limited financial resources and a lack of support from the hearing community.

Before Henry left USD in 1890, he was the principal for five years. However, the impact of oralism spread across the country after the infamous Milan Conference of 1880 passed a resolution requiring using the oral method in deaf education. As a result, Henry's job was jeopardized. The oral movement in Utah reflected Henry's replacement as principal in 1889 by a hearing teacher from the Kansas School for the Deaf, Frank W. Metcalf (Evans, 1999).

When Frank was appointed principal in 1889, Henry took over as head teacher. He was enmity toward his successor, Frank and this conflict caused disputes between them. The Board of Regents investigated the situation and terminated Henry's employment with the school (The Utah Eagle, February 1922). He severed his ties with the school in February 1890 (White, 1890; Fay, 1893; Pace, 1946; Burdett; Utah School for the Deaf Brochure).

Professor White was not, in fact, alone in this situation. Deaf men who founded state schools for the deaf faced a similar challenge and were fired as principals for no reason other than being deaf. The Deaf community believed hearing people preferred hearing people to hold the positions. Professor White, along with three other Deaf principals, J.M. Koehler of Pennsylvania, A.R. Spear of North Dakota, and Mr. Long of the Indian Territory, were recognized as "shining lights in this particular, all men who built on firm foundations at the price of great discomfort and in the face of great sacrifices, only to be told to "get out" and make room for hearing men" (The Silent Worker, March 1900, p. 101). At the time, the national Deaf community regarded Professor White as one of the founders, completely unaware of the involvement of two parents, John Beck, and William Wood, in establishing the Utah School for the Deaf.

During Professor White's last year at the school, Frank M. Driggs, the school's then-boys' supervisor and long-time superintendent, got to know him and found him to be "well-educated, bright, alert, and active." Mr. Driggs was praised for 'his efforts to keep the school going during those early years when it required money and courage' (The Utah Eagle, February 1922, p. 2).

While Deaf leaders were battling Alexander Graham Bell, a well-known oral advocate, and attempting to halt the spread of oral day schools across the United States in 1894, Henry C. White, a gifted rhetorician, condemned school administrators for failing to consult directly with Deaf adults. "What of the Deaf themselves?" he wondered. "Have they no say in a matter which means intellectual life and death to them?" (Buchanan, 1850-1950, p. 28). During this time, Henry was one of the most foresighted Deaf activists, predicting that Deaf activists would be unable to mount the type of national campaign. Henry, according to Buchanan (1850-1950), "believed that deaf instructors had a moral claim in teaching positions, but he understood that such assertions were nothing if they were not based in law and protected by vigilant Deaf adults" (p. 32). Henry urged his peers at the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City in 1885 to define, organize, and defend a new set of rights. "One thing must be made clear, and if we wish to combat this lingering prejudice and secure justice...we must assert our claims to justice, or we will never receive it," he said (p. 32). Henry had clearly not forgotten the incident in Utah.

Soon after he graduated, Henry became the manager of a home for older Deaf people in Allston, Massachusetts (Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866–1957). Then, on the advice of Dr. Edward M. Gallaudet, president of Gallaudet College, Dr. John R. Park, president of the University of Utah, made Henry the first principal of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1884. The Legislature created the school as a part of the state university because John Beck and William Wood, both parents of Deaf children, pushed for it. It opened in a room in the University building on August 26, 1884 (The Utah Eagle, February 1922). Henry stayed at USD as a teacher, principal, and head teacher until 1890. Although Henry C. White did not found the Utah School for the Deaf, he is credited with leading and maintaining it, which still exists today, as a leader and administrator despite limited financial resources and a lack of support from the hearing community.

Before Henry left USD in 1890, he was the principal for five years. However, the impact of oralism spread across the country after the infamous Milan Conference of 1880 passed a resolution requiring using the oral method in deaf education. As a result, Henry's job was jeopardized. The oral movement in Utah reflected Henry's replacement as principal in 1889 by a hearing teacher from the Kansas School for the Deaf, Frank W. Metcalf (Evans, 1999).

When Frank was appointed principal in 1889, Henry took over as head teacher. He was enmity toward his successor, Frank and this conflict caused disputes between them. The Board of Regents investigated the situation and terminated Henry's employment with the school (The Utah Eagle, February 1922). He severed his ties with the school in February 1890 (White, 1890; Fay, 1893; Pace, 1946; Burdett; Utah School for the Deaf Brochure).

Professor White was not, in fact, alone in this situation. Deaf men who founded state schools for the deaf faced a similar challenge and were fired as principals for no reason other than being deaf. The Deaf community believed hearing people preferred hearing people to hold the positions. Professor White, along with three other Deaf principals, J.M. Koehler of Pennsylvania, A.R. Spear of North Dakota, and Mr. Long of the Indian Territory, were recognized as "shining lights in this particular, all men who built on firm foundations at the price of great discomfort and in the face of great sacrifices, only to be told to "get out" and make room for hearing men" (The Silent Worker, March 1900, p. 101). At the time, the national Deaf community regarded Professor White as one of the founders, completely unaware of the involvement of two parents, John Beck, and William Wood, in establishing the Utah School for the Deaf.

During Professor White's last year at the school, Frank M. Driggs, the school's then-boys' supervisor and long-time superintendent, got to know him and found him to be "well-educated, bright, alert, and active." Mr. Driggs was praised for 'his efforts to keep the school going during those early years when it required money and courage' (The Utah Eagle, February 1922, p. 2).

While Deaf leaders were battling Alexander Graham Bell, a well-known oral advocate, and attempting to halt the spread of oral day schools across the United States in 1894, Henry C. White, a gifted rhetorician, condemned school administrators for failing to consult directly with Deaf adults. "What of the Deaf themselves?" he wondered. "Have they no say in a matter which means intellectual life and death to them?" (Buchanan, 1850-1950, p. 28). During this time, Henry was one of the most foresighted Deaf activists, predicting that Deaf activists would be unable to mount the type of national campaign. Henry, according to Buchanan (1850-1950), "believed that deaf instructors had a moral claim in teaching positions, but he understood that such assertions were nothing if they were not based in law and protected by vigilant Deaf adults" (p. 32). Henry urged his peers at the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City in 1885 to define, organize, and defend a new set of rights. "One thing must be made clear, and if we wish to combat this lingering prejudice and secure justice...we must assert our claims to justice, or we will never receive it," he said (p. 32). Henry had clearly not forgotten the incident in Utah.

After Henry quit his job at the Utah School for the Deaf, he moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where he worked as a printer for Acheson & Co. and published his newspaper, The National Gazette (The Silent Worker, June 1895; The Utah Eagle, February 1922; Gannon, 1981).

He eventually became an attorney and worked as a legal advisor. He also wrote a book called Law Points for Everybody, which sold 60,000 copies in New England in a month. Copies of a second edition were on order. His book about law covered New England and New York (The Silent Worker, June 1898). He sometimes worked with other lawyers in court cases involving the deaf and often acted as an interpreter on behalf of other deaf people. For example, he once assisted John L. Bates, a former governor of Massachusetts, with a critical case. Even though Henry didn't practice law, he became known as a teacher of the deaf in eastern cities (The Silent Worker, July 1912). He was a brilliant person.

Edward Allen Fay, a professor at Gallaudet College and the editor of the American Annals of the Deaf, wrote about Henry's strong English skills in March 1916 (The Silent Worker, April 1916):

"The value of this means of acquiring languages seems to have been discovered by a man who was himself deaf Henry C. White, then a student at Gallaudet College. Seeing that some of his fellow-students who were congenitally or quasicongenitally deaf had a much better command of the English language than others of equally good natural advantages and an equally long term of instruction, he sought the cause of this difference. He found it in the circumstance that those who understood and wrote English well were eager reader of books, while those whose command of English was inferior bad, like the great majority of deaf-born people, no taste for reading, and did little more of it than was required by the instructors."

He eventually became an attorney and worked as a legal advisor. He also wrote a book called Law Points for Everybody, which sold 60,000 copies in New England in a month. Copies of a second edition were on order. His book about law covered New England and New York (The Silent Worker, June 1898). He sometimes worked with other lawyers in court cases involving the deaf and often acted as an interpreter on behalf of other deaf people. For example, he once assisted John L. Bates, a former governor of Massachusetts, with a critical case. Even though Henry didn't practice law, he became known as a teacher of the deaf in eastern cities (The Silent Worker, July 1912). He was a brilliant person.

Edward Allen Fay, a professor at Gallaudet College and the editor of the American Annals of the Deaf, wrote about Henry's strong English skills in March 1916 (The Silent Worker, April 1916):

"The value of this means of acquiring languages seems to have been discovered by a man who was himself deaf Henry C. White, then a student at Gallaudet College. Seeing that some of his fellow-students who were congenitally or quasicongenitally deaf had a much better command of the English language than others of equally good natural advantages and an equally long term of instruction, he sought the cause of this difference. He found it in the circumstance that those who understood and wrote English well were eager reader of books, while those whose command of English was inferior bad, like the great majority of deaf-born people, no taste for reading, and did little more of it than was required by the instructors."

In June 1885, Henry married Mary Elizabeth Mann, who was also deaf and a graduate of the Ohio School for the Deaf (Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866–1957; The Salt Lake Herald, June 20, 1885; The Utah Eagle, February 1922). They were parents of three children: Emma Frances, Howard M., and Harriet Tuttle.

In 1911, Henry founded the Arizona School for the Deaf at the University of Arizona. It was similar to the one in Utah. During his three years as a principal, "he worked hard and put the school and its students first." Unfortunately, when ASD became an oral school, Henry's job was terminated in the middle of the school year for no reason, and he couldn't find another job (The Silent Worker, March 1920). In March 1913, Henry wrote the following about oralism in "The Silent Worker" magazine:

"Oralists never taught by any method but their own and cannot be expected to appreciate the utility of other methods than their own. They are not in touch with the deaf at all, for their own graduates turn against them and their method, after they have gone out into the stress and strife of life's battles and found themselves worse handicapped than their more fortunate brethren and sisters whose lives had been rounded out by the combined system."

After a few years, John T. Hughes, Chancellor of the University of Arizona, brought a bill to the Legislature to honor Henry's work at the ASD on March 12, 1919 (The Silent Worker, March 1920). Henry passed away at the County Hospital in Chicago, Illinois on December 31, 1921 (Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866–1957; The Utah Eagle, February 1922).

In 1911, Henry founded the Arizona School for the Deaf at the University of Arizona. It was similar to the one in Utah. During his three years as a principal, "he worked hard and put the school and its students first." Unfortunately, when ASD became an oral school, Henry's job was terminated in the middle of the school year for no reason, and he couldn't find another job (The Silent Worker, March 1920). In March 1913, Henry wrote the following about oralism in "The Silent Worker" magazine:

"Oralists never taught by any method but their own and cannot be expected to appreciate the utility of other methods than their own. They are not in touch with the deaf at all, for their own graduates turn against them and their method, after they have gone out into the stress and strife of life's battles and found themselves worse handicapped than their more fortunate brethren and sisters whose lives had been rounded out by the combined system."

After a few years, John T. Hughes, Chancellor of the University of Arizona, brought a bill to the Legislature to honor Henry's work at the ASD on March 12, 1919 (The Silent Worker, March 1920). Henry passed away at the County Hospital in Chicago, Illinois on December 31, 1921 (Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866–1957; The Utah Eagle, February 1922).

Did You Know?

Dr. Edward Allen Fay said, "One of the most important aids in the acquisition of language by the deaf is much reading of books. From the frequent repetition of words and phrases, by which the hearing child unconsciously acquires language through the ear, the deaf are wholly shut off: reading and reading alone can give them this needed repetition" (The Silent Worker, April 1916).

References

Buchanan, Robert M. Illusion of Equality: Deaf Americans in school and factory 1850 -1950 (Online. Available HTTP: http://books.google.com/books?id=Tahfhls7TKYC&pg=PA28&sig=VbCZINlmYggHd34t9GD_udkD_dY&dq=this+of+utah+school+for+the+deaf+%221894%22+%22In+1894,+Portland%27s+newspapers+carried+a+series+of+exchanges+that+pitted+American+School+officials+and+deaf+activists+against+Bell+and+Yale.%22

Burdett, Kenneth C. (1960s). Utah School for the Deaf Brochure.

Census of Henry C. White.

Fay, Edward Allen. History of the Utah School for the Deaf - History of American Schools for the Deaf. 1817 – 1893. School of Education Library; Stanford University Libraries: The Volta Bureau, 1893. http://books.google.com/books?id=tjEWAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA21-PA10&lpg=RA21-PA10&dq=Frank+M.+Driggs,+deaf&source=web&ots=il1POQSsle&sig=5L_Ewyv3YcTrbGyafwB4psnD-k0&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#PRA21-PA10,M1

Evans, David S. A Silent World In The Intermountain West: Records From The Utah School For The Deaf and Blind, 1884-1941. Utah State University: Logan, Utah. 1999.

Fay, Edward Allen. History of the Utah School for the Deaf - History of American Schools for the Deaf. 1817 – 1893.School of Education Library; Stanford University Libraries: The Volta Bureau, 1893.

http://books.google.com/books?id=tjEWAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA21-PA10&lpg=RA21-PA10&dq=Frank+M.+Driggs,+Deaf&source=web&ots=il1POQSsle&sig=5L_Ewyv3YcTrbGyafwB4psnD-k0&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#v=onepage&q=Frank%20M.%20Driggs%2C%20Deaf&f=false

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. American Annals of the Deaf.Washington, D.C. Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf: American Annals of the Deaf, 1911.

http://books.google.com/books?id=d8AJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA455&lpg=PA455&dq=Elsie+Christiansen,+utah+and+deaf&source=bl&ots=ovSqzoQyv4&sig=0BXfmLY9_R5wE_G1LSU4KUbTUDc&hl=en&ei=_VdyTqSYJ8GlsQKSuPTCCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&sqi=2&ved=0CDgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Elsie%20Christiansen%2C%20utah%20and%20deaf&f=false

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. American Annals of the Deaf.Washington, D.C. Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf, 1916. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZqlKAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA461&lpg=PA461&dq=Mary+Woolslayer+utah+deaf&source=bl&ots=lmFN_lM-J8&sig=GoVttIsw68vn5YTT0kn21OCyGow&hl=en&ei=-X5zTuOLFa6EsALR68yLBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CDsQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Mary%20Woolslayer%20utah%20deaf&f=false

Gannon, Jack, R. Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America. Silver Spring, Maryland: National Association of the Deaf, 1981.

“Henry C. White.” The Utah Eagle, Vol. 33, no. 5 (February 1922): 1-2.

“Industrial Department." The Silent Worker, vol. 7. no. 10 (June 1895): 12. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/31446

“Mr. White Awarded.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32, no. 6. (June 1920): 149. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38064

“Mutely Married: Their wedding bells heard only by their happy hearts.” The Salt Lake Herald 1870-1909 (June 20, 1885): 8.

Pace, Irma Acord. “A History of the Utah School for the Deaf.” The Utah Eagle, vol. 58, no. 1 (October 1946): 1-33.

“The Kinetoscope and Telephone” The Silent Worker, vol. 12 no. 7 (March 1900): 101. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/32729

“The Silent Worker.” The Silent Worker, vol. 10 no. 10 (June 1898): 155. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/32324

White, Henry C.: B.A., 1880. Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866-1957. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/45187

White, Henry C. American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb. vol. 35 (July 1890): 221.

Burdett, Kenneth C. (1960s). Utah School for the Deaf Brochure.

Census of Henry C. White.

Fay, Edward Allen. History of the Utah School for the Deaf - History of American Schools for the Deaf. 1817 – 1893. School of Education Library; Stanford University Libraries: The Volta Bureau, 1893. http://books.google.com/books?id=tjEWAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA21-PA10&lpg=RA21-PA10&dq=Frank+M.+Driggs,+deaf&source=web&ots=il1POQSsle&sig=5L_Ewyv3YcTrbGyafwB4psnD-k0&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#PRA21-PA10,M1

Evans, David S. A Silent World In The Intermountain West: Records From The Utah School For The Deaf and Blind, 1884-1941. Utah State University: Logan, Utah. 1999.

Fay, Edward Allen. History of the Utah School for the Deaf - History of American Schools for the Deaf. 1817 – 1893.School of Education Library; Stanford University Libraries: The Volta Bureau, 1893.

http://books.google.com/books?id=tjEWAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA21-PA10&lpg=RA21-PA10&dq=Frank+M.+Driggs,+Deaf&source=web&ots=il1POQSsle&sig=5L_Ewyv3YcTrbGyafwB4psnD-k0&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#v=onepage&q=Frank%20M.%20Driggs%2C%20Deaf&f=false

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. American Annals of the Deaf.Washington, D.C. Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf: American Annals of the Deaf, 1911.

http://books.google.com/books?id=d8AJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA455&lpg=PA455&dq=Elsie+Christiansen,+utah+and+deaf&source=bl&ots=ovSqzoQyv4&sig=0BXfmLY9_R5wE_G1LSU4KUbTUDc&hl=en&ei=_VdyTqSYJ8GlsQKSuPTCCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&sqi=2&ved=0CDgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Elsie%20Christiansen%2C%20utah%20and%20deaf&f=false

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. American Annals of the Deaf.Washington, D.C. Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf, 1916. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZqlKAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA461&lpg=PA461&dq=Mary+Woolslayer+utah+deaf&source=bl&ots=lmFN_lM-J8&sig=GoVttIsw68vn5YTT0kn21OCyGow&hl=en&ei=-X5zTuOLFa6EsALR68yLBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CDsQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Mary%20Woolslayer%20utah%20deaf&f=false

Gannon, Jack, R. Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America. Silver Spring, Maryland: National Association of the Deaf, 1981.

“Henry C. White.” The Utah Eagle, Vol. 33, no. 5 (February 1922): 1-2.

“Industrial Department." The Silent Worker, vol. 7. no. 10 (June 1895): 12. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/31446

“Mr. White Awarded.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32, no. 6. (June 1920): 149. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38064

“Mutely Married: Their wedding bells heard only by their happy hearts.” The Salt Lake Herald 1870-1909 (June 20, 1885): 8.

Pace, Irma Acord. “A History of the Utah School for the Deaf.” The Utah Eagle, vol. 58, no. 1 (October 1946): 1-33.

“The Kinetoscope and Telephone” The Silent Worker, vol. 12 no. 7 (March 1900): 101. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/32729

“The Silent Worker.” The Silent Worker, vol. 10 no. 10 (June 1898): 155. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/32324

White, Henry C.: B.A., 1880. Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866-1957. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/45187

White, Henry C. American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb. vol. 35 (July 1890): 221.

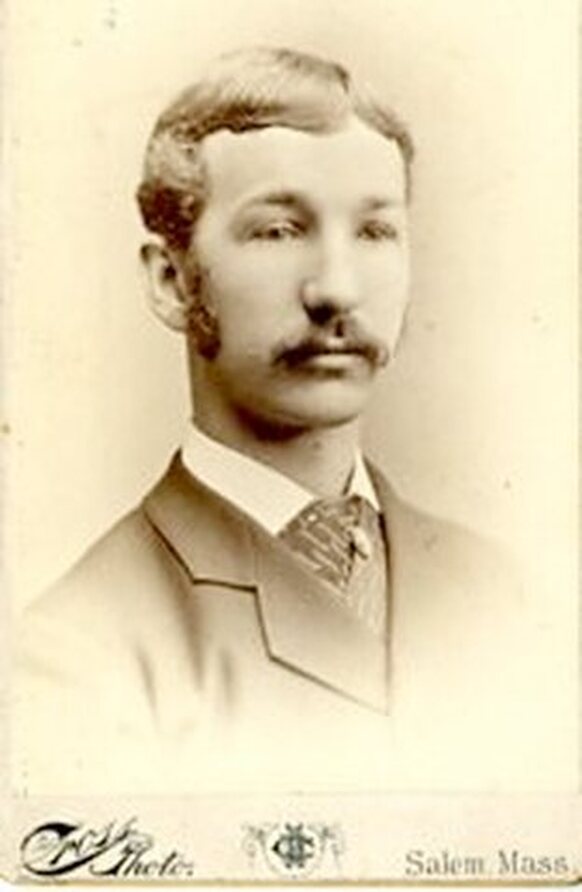

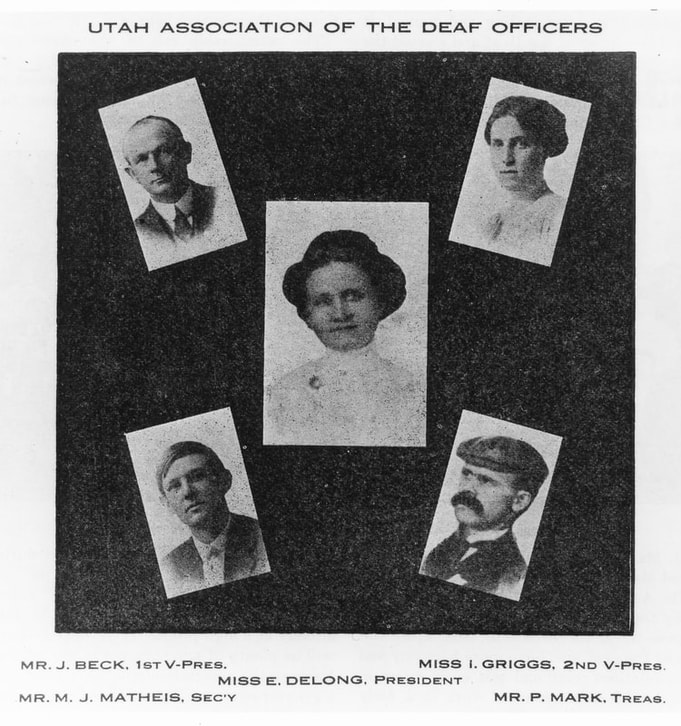

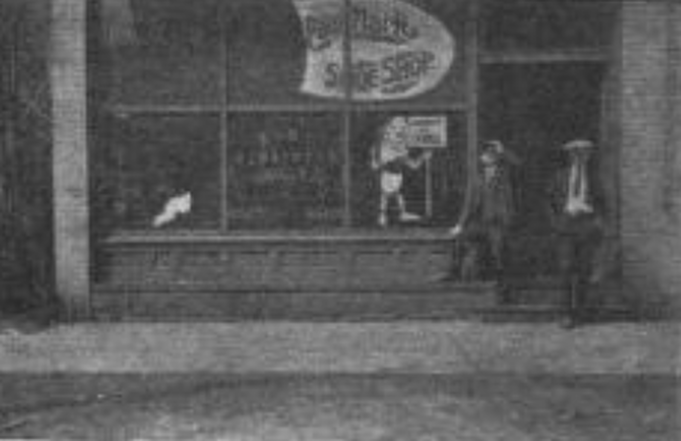

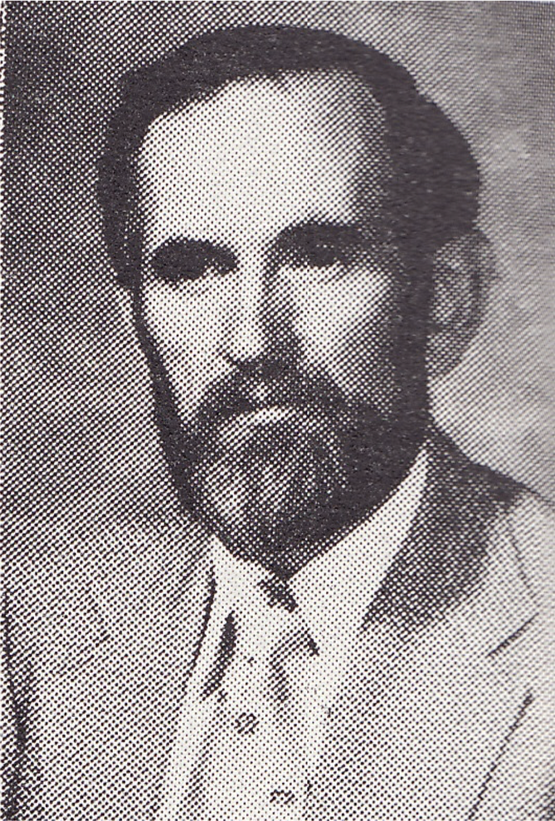

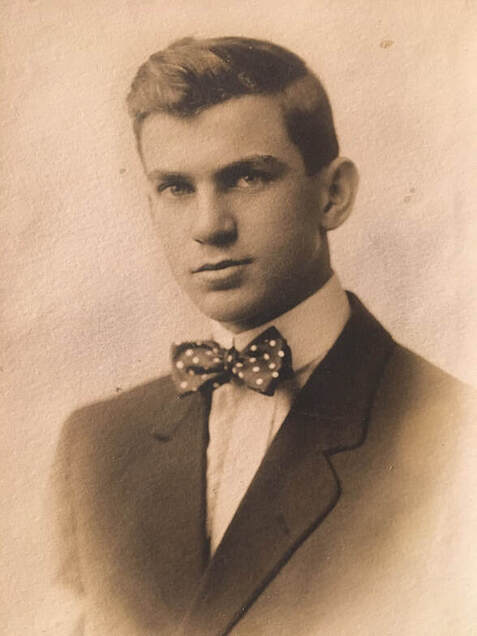

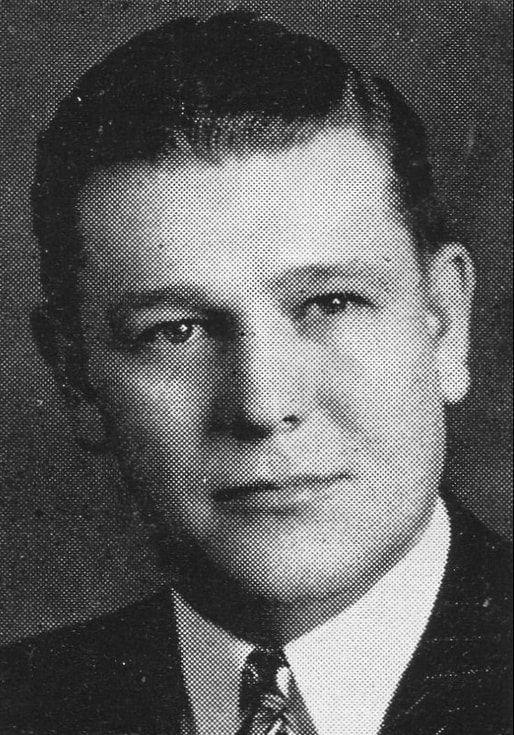

Paul Mark, Popular Leader

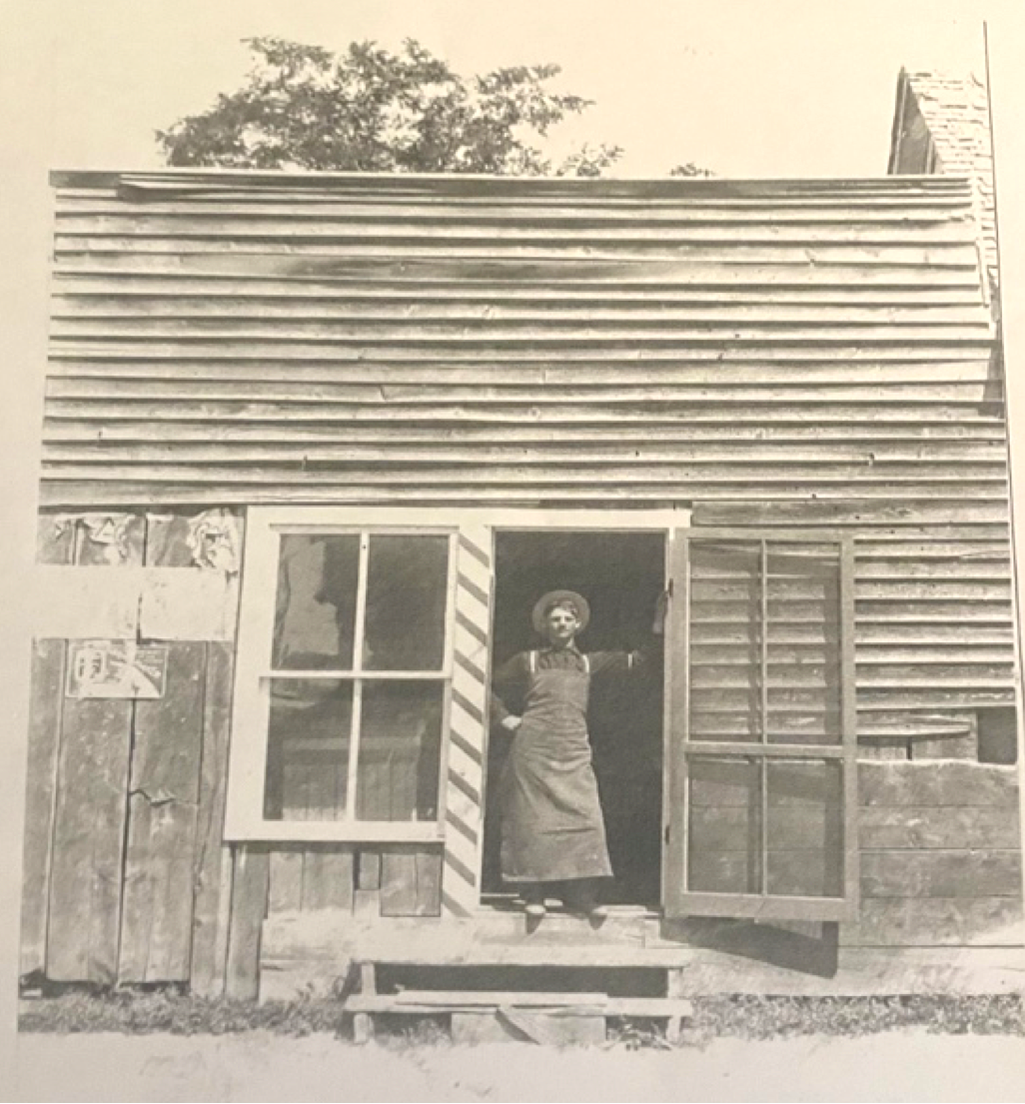

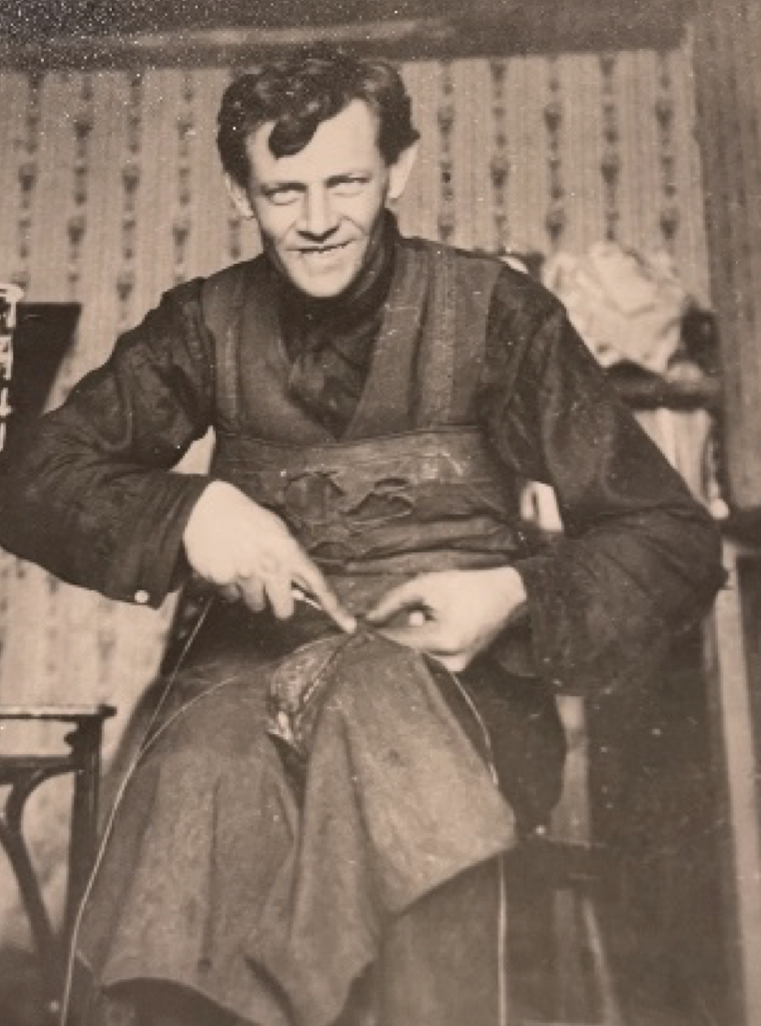

Paul Mark was elected president of the Utah Association of the Deaf in 1915. He held this position for three years, from 1915 to 1918. He was also the president of the local chapter of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf. He owned a shoe shop called "Dunn and Bradstreet" on 25th Street in Ogden, Utah. In his spare time, he enjoyed driving his Peerless car. In the year 1920, Paul was Utah's most popular Deaf leader. Members of the Deaf community would always call Mark for the most up-to-date information on the Deaf community. He held meetings in his shoe shop and invited Deaf members to stay with him.

Paul Mark was born in Utah on September 17, 1872, in Brigham City, Utah.

In the 1880 census, Paul is listed as living in Terrace, Box Elder County, with his parents, Nicholas and Ann Mark. Terrace is now a ghost town in the Great Salt Lake Desert in west-central Box Elder County.

Paul graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1892 (The Utah Eagle, November 15, 1909).

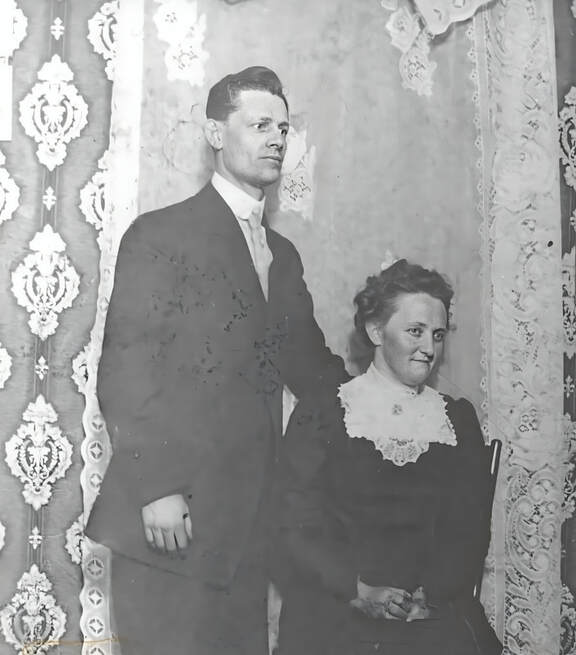

Paul married Theresa Maria Rasche, also deaf, on November 15, 1899, and had four children: Pauline Veronica, Theodore Paul, Nathaniel Cullen, and Nicholas Paul. The family belonged to the Catholic faith.

In the 1880 census, Paul is listed as living in Terrace, Box Elder County, with his parents, Nicholas and Ann Mark. Terrace is now a ghost town in the Great Salt Lake Desert in west-central Box Elder County.

Paul graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1892 (The Utah Eagle, November 15, 1909).

Paul married Theresa Maria Rasche, also deaf, on November 15, 1899, and had four children: Pauline Veronica, Theodore Paul, Nathaniel Cullen, and Nicholas Paul. The family belonged to the Catholic faith.

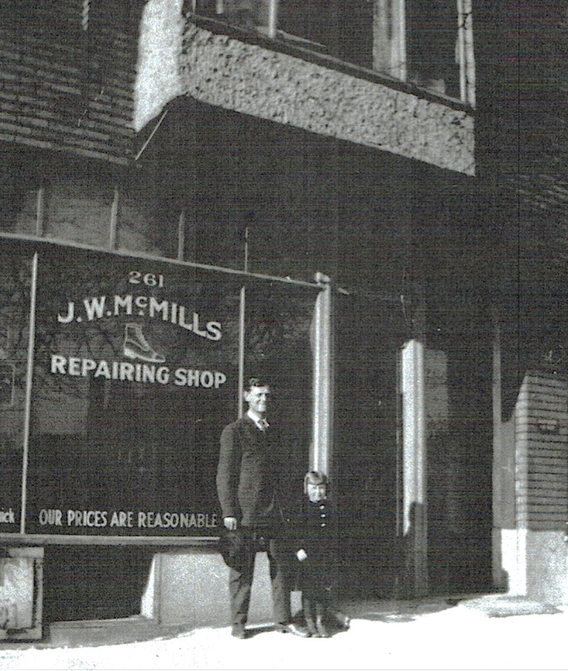

Paul ran for president of the Utah Association of the Deaf on June 10, 1909, but lost to Elizabeth DeLong, the association's first woman president. He did not become president of the Utah Association of the Deaf until 1915, a position he held for three years until 1918. He was also the president of the local chapter of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf. He had a family, owned a house, and spent his spare time driving his Peerless (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920).

Paul was the most popular leader of the Utah Deaf community in 1920. He was a very modest man. He lived in Ogden, Utah, for many years and was well-liked by everyone who knew him (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920). On 25th Street, he ran a "Dunn and Bradstreet" shop. Paul became a successful business owner and stockholder in several of Ogden's leading industries (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920; White, The Silent Worker, October 1920). More than 150 pairs of shoes were sometimes repaired in a single day. Paul's business became so busy one day that he was forced to work past his regular closing time. Cyril Jones, the Deaf father of two Deaf sons, Von and Rollin Jones of Logan, became his assistant and eventually secured employment with his "Prince of Good Fellows" shop (White, The Silent Worker, June 1920).

When members of the Utah Deaf community needed to know what was going on with other deaf people, they checked with Mark. He held the gatherings in his shoe shop and invited Deaf members from all over the state to attend (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920).

When members of the Utah Deaf community needed to know what was going on with other deaf people, they checked with Mark. He held the gatherings in his shoe shop and invited Deaf members from all over the state to attend (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920).

In 1920, Paul invited Harry C. Anderson, president of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, to ride in his "prairie shooner," a Peerless car, through the trail from Ogden Canyon to the Heritage Hotel, where President Anderson and his wife stayed during their visit to Ogden, Utah (White, The Silent Worker, November 1920).

Paul passed away on December 28, 1945, Culver City, Los Angeles, California, and is buried at the Aultorest Memorial Park in Ogden with his wife and his parents.

References

Paul Mark, 92. School for the Deaf. The Utah Eagle. November 15, 1909.

White, Bob. "Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons." The Silent Worker vol. 32 no. 7, April 1920. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38096

White, Bob. “Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32, no. 9, June 1920.

White, Bob. “Ogden’s Social and Religious Center.” The Silent Worker vol. 33 no. 1, October 1920. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38209

White, Bob. “Winding Trails.” The Silent Worker, vol. 33, no. 2, November 1920. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38227

White, Bob. "Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons." The Silent Worker vol. 32 no. 7, April 1920. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38096

White, Bob. “Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32, no. 9, June 1920.

White, Bob. “Ogden’s Social and Religious Center.” The Silent Worker vol. 33 no. 1, October 1920. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38209

White, Bob. “Winding Trails.” The Silent Worker, vol. 33, no. 2, November 1920. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/38227

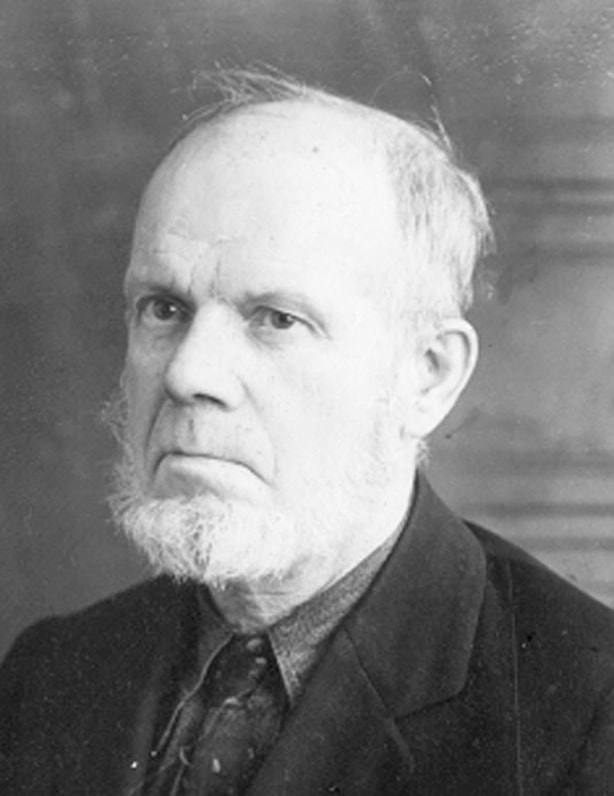

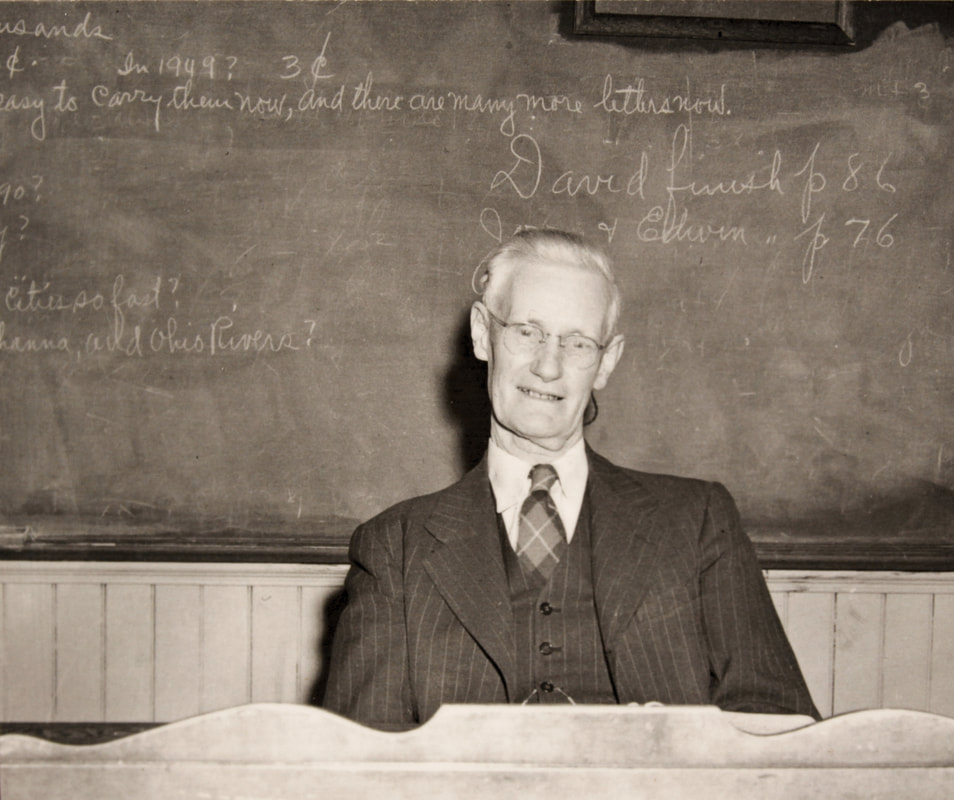

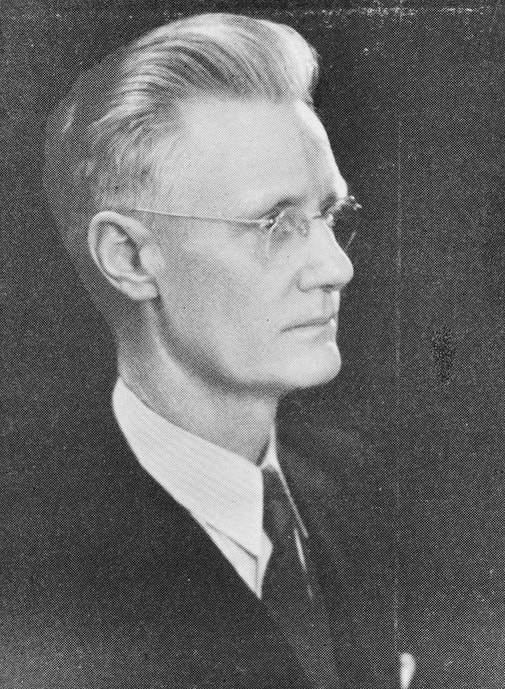

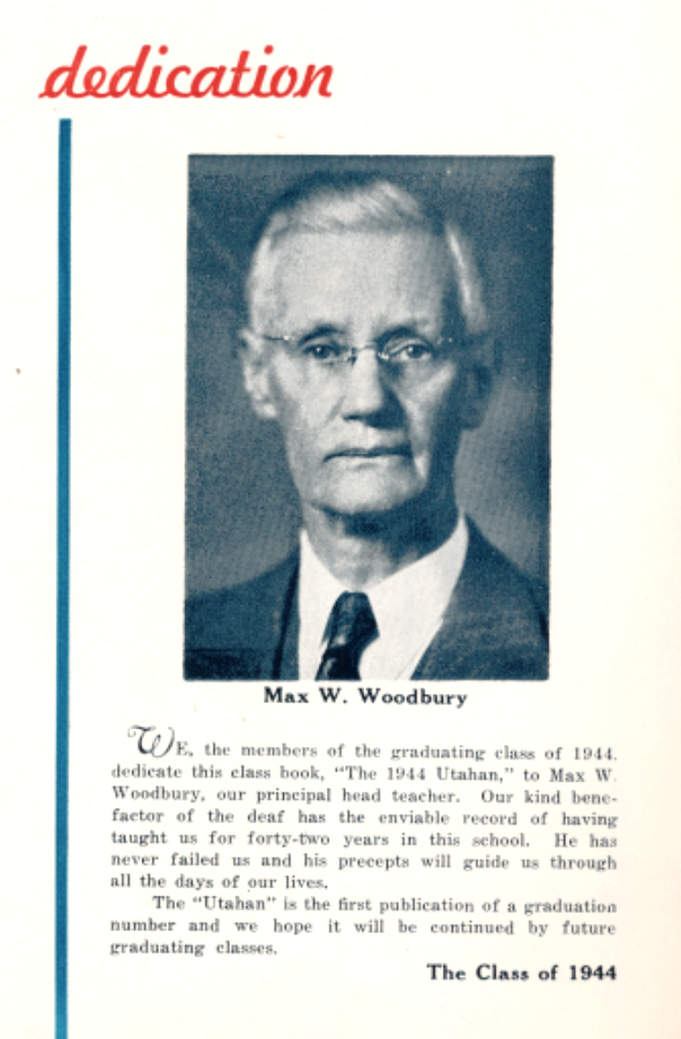

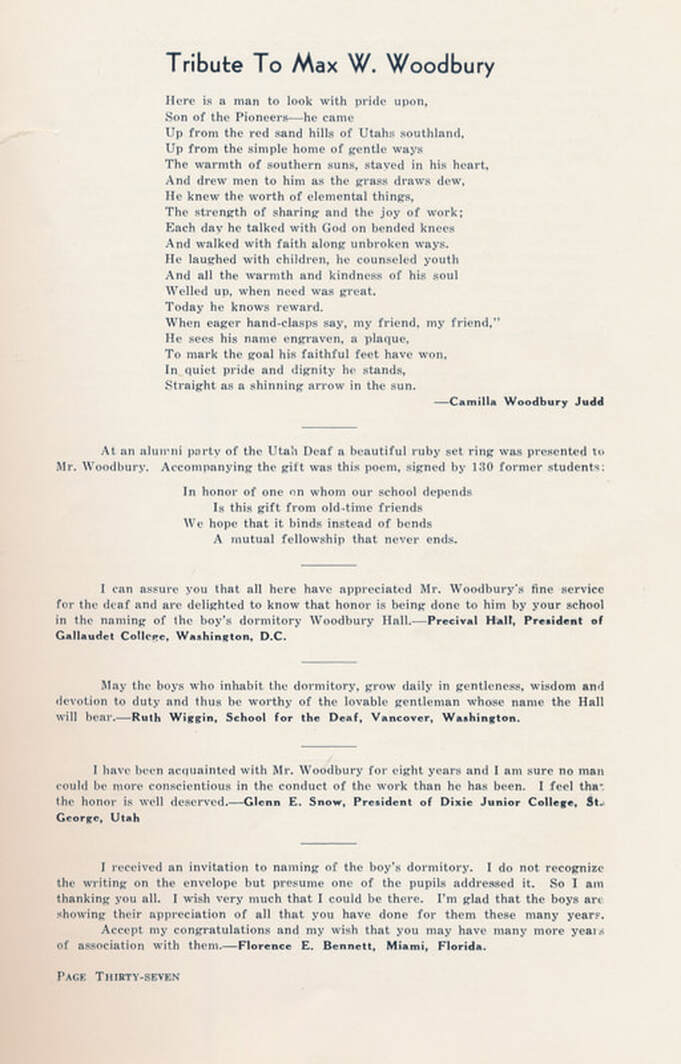

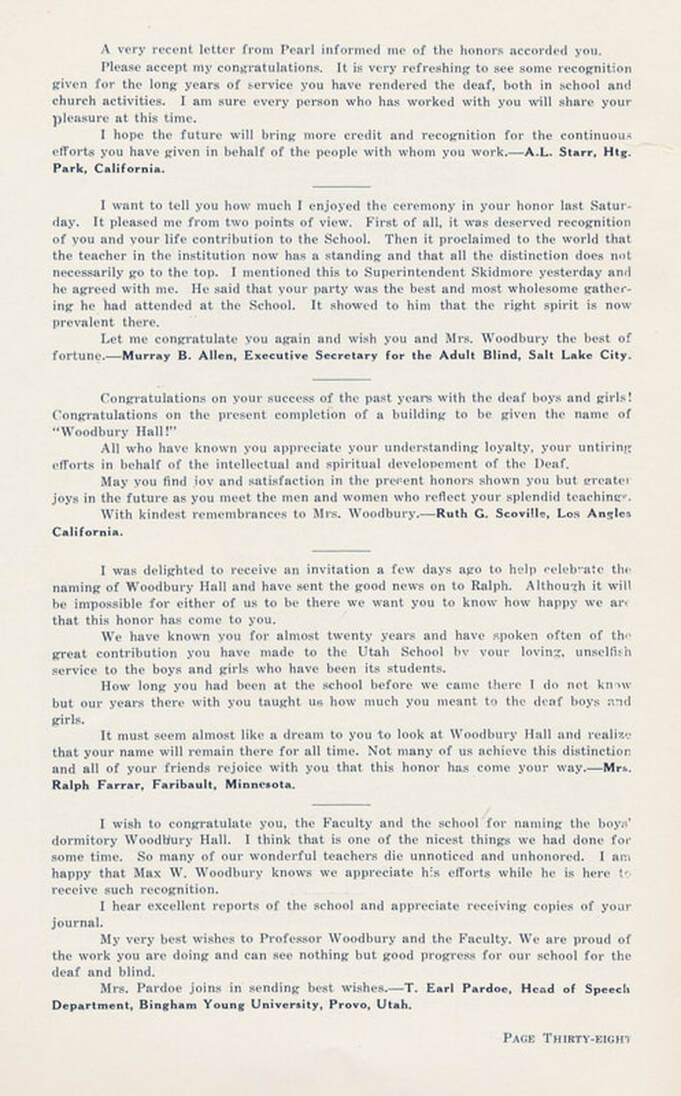

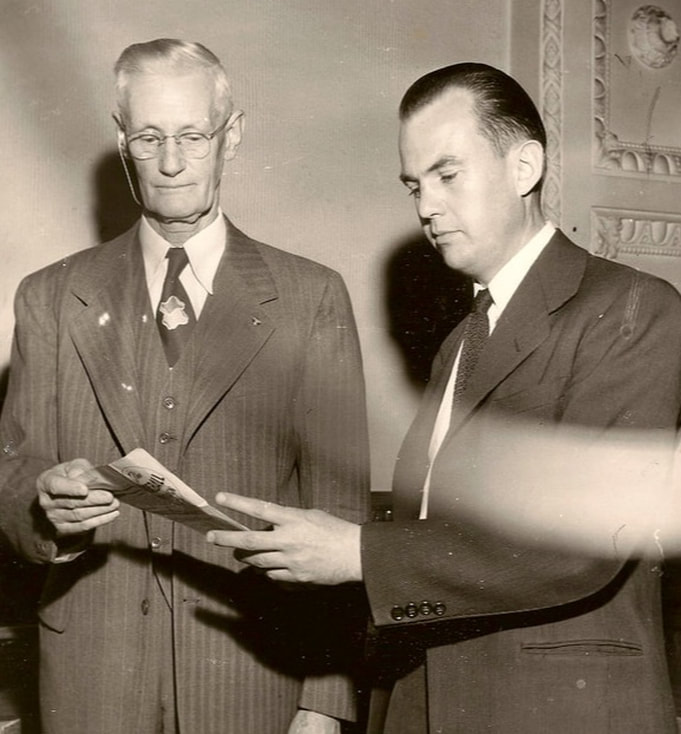

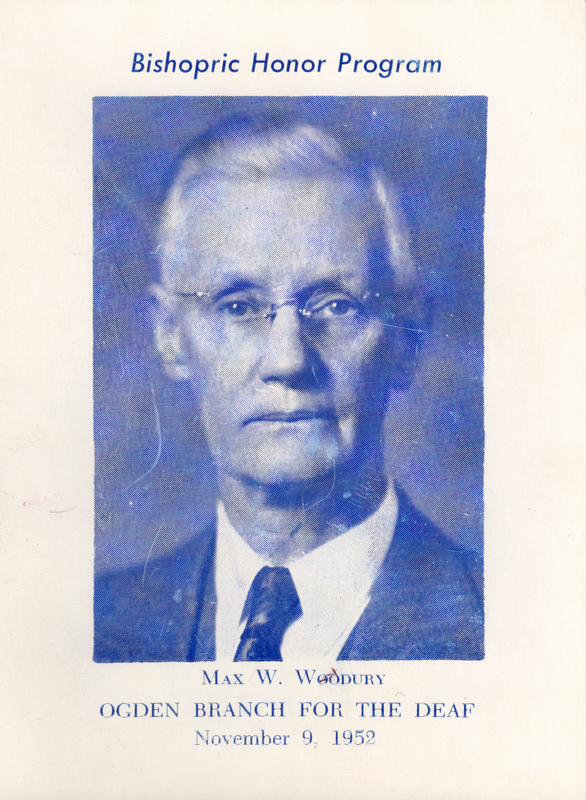

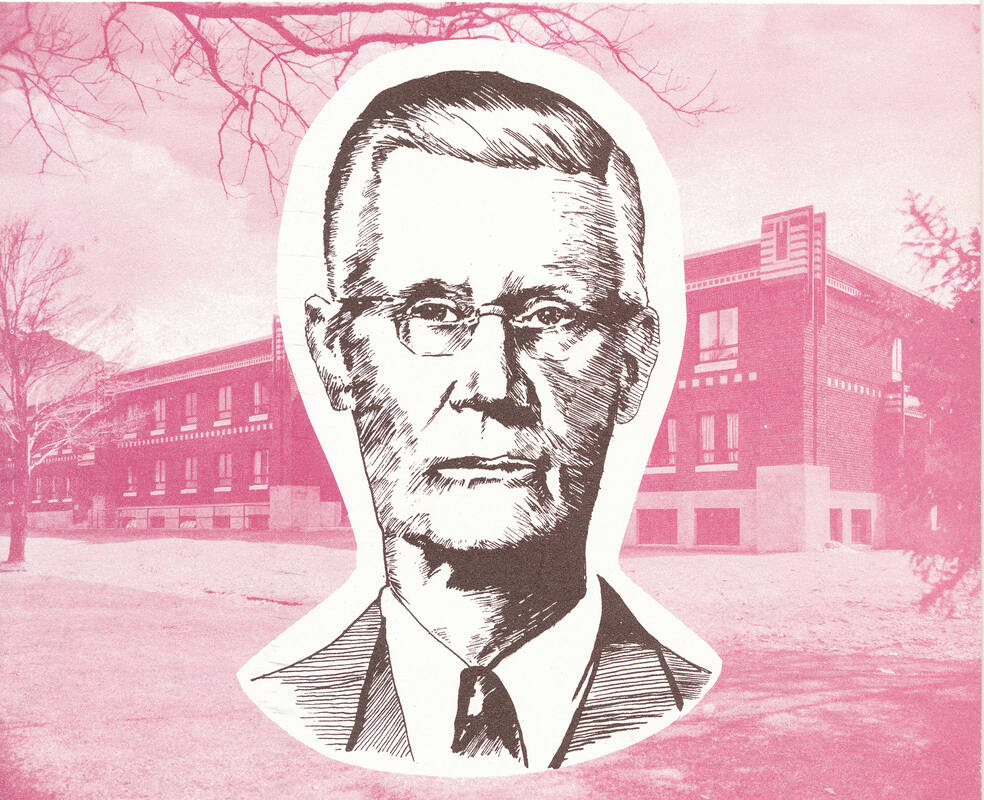

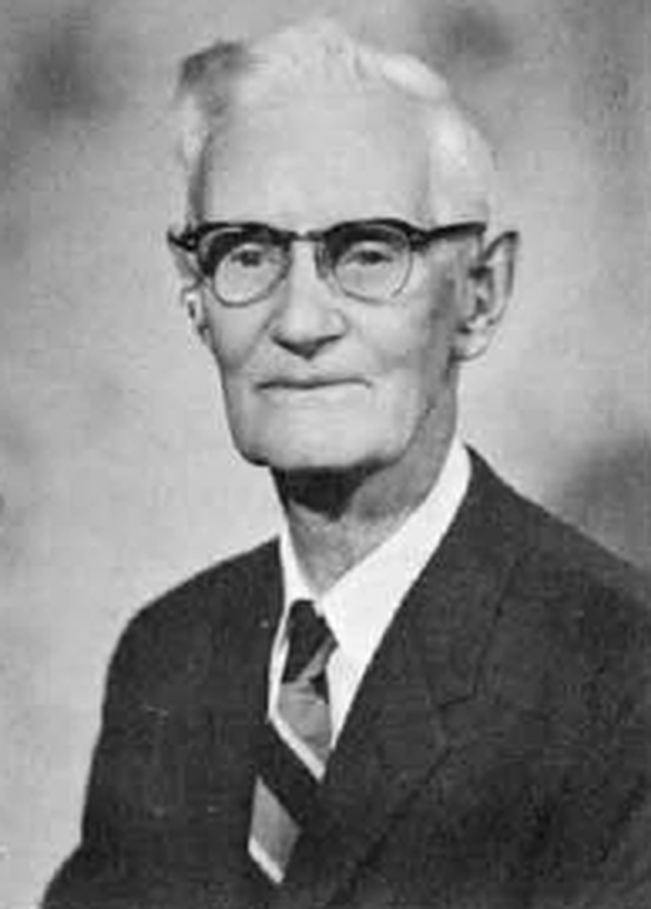

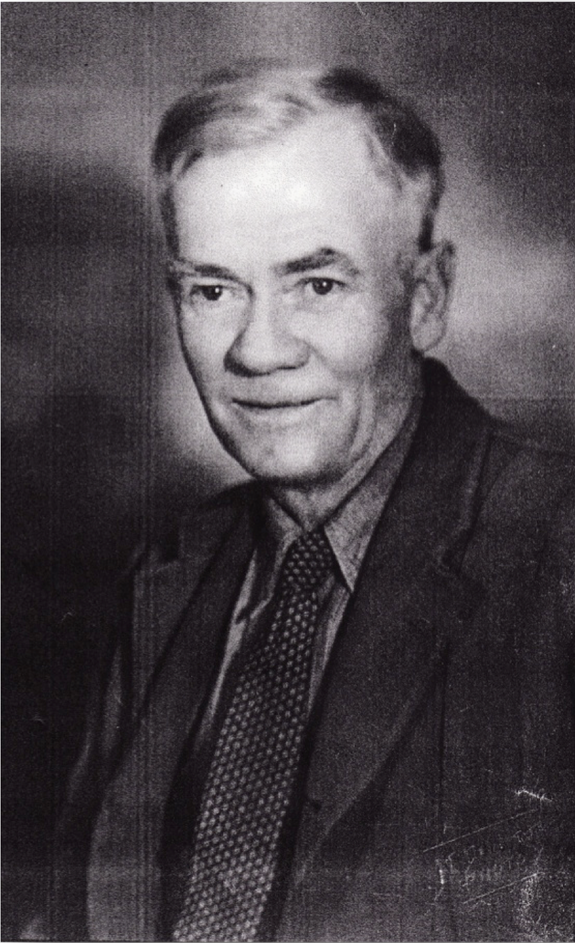

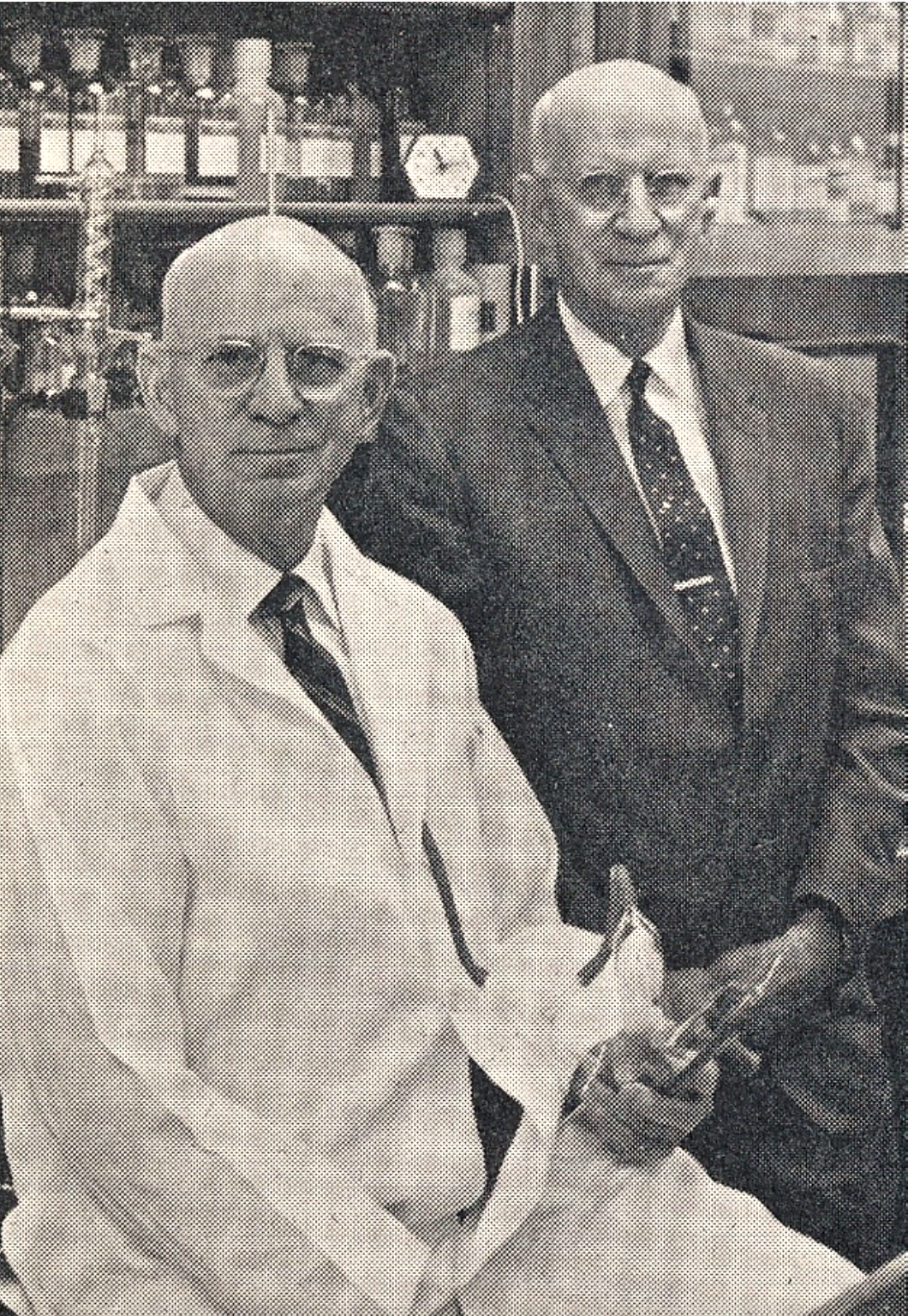

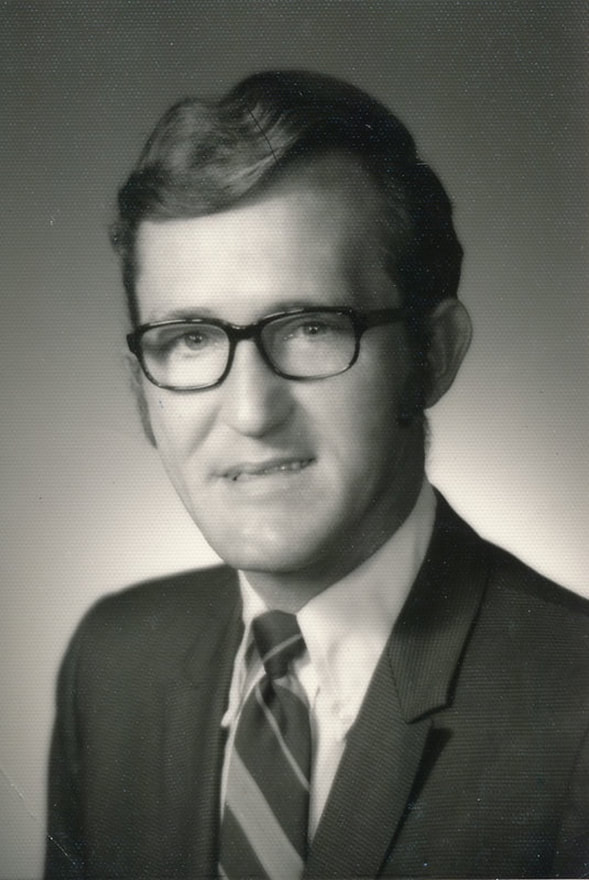

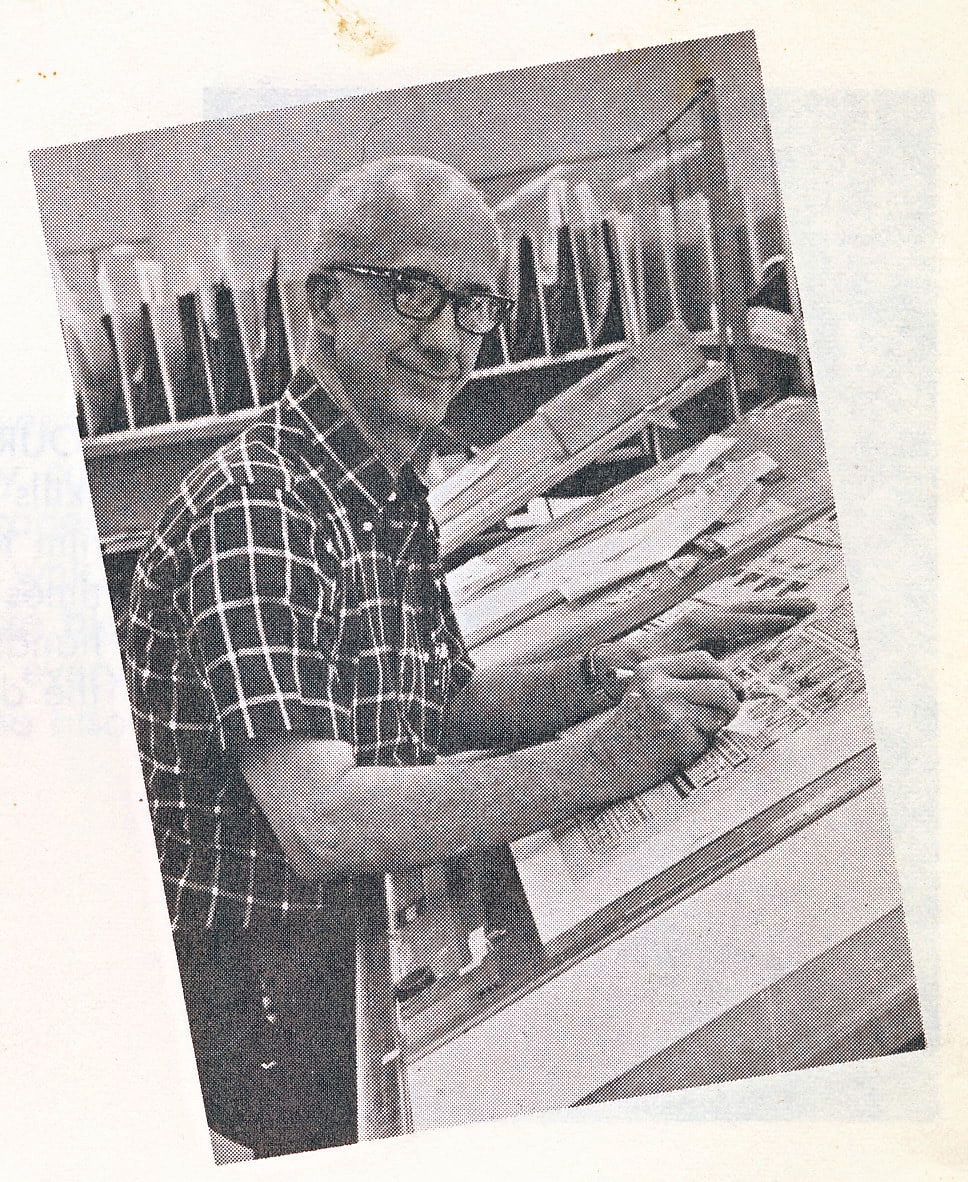

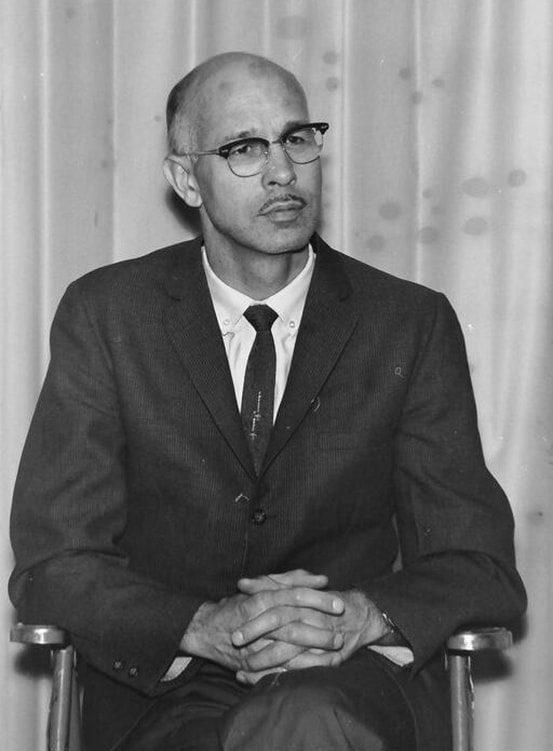

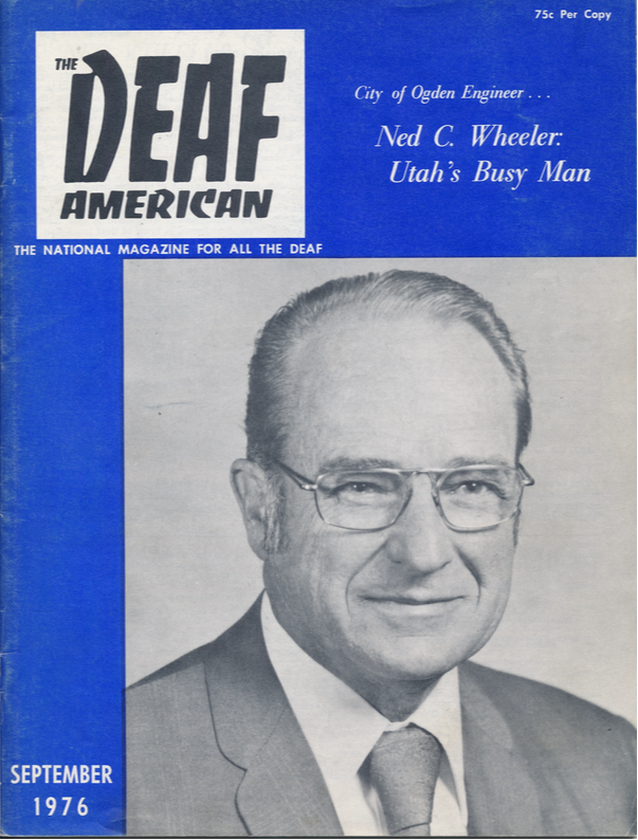

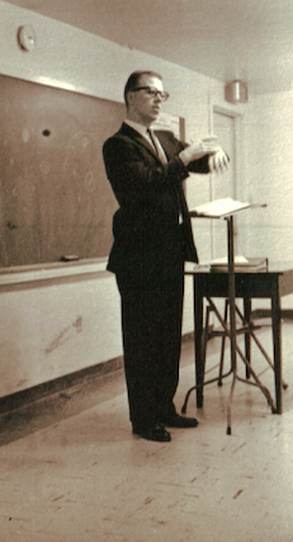

Max W. Woodbury, Ecclesiastical Leader

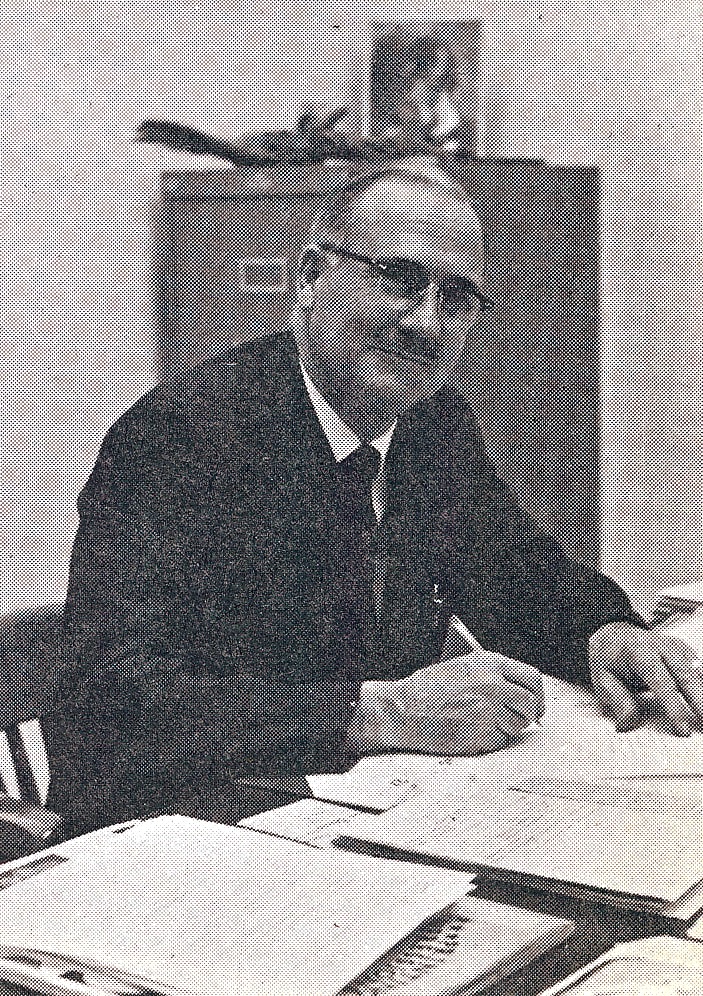

Max W. Woodbury dedicated his life to deaf education at the Utah School for the Deaf, where he worked as a teacher, teacher-supervising teacher, and finally, principal. From 1917 through 1968, he was president of the Ogden Branch for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for 51 years. He is "believed to have set a record in the Church" for serving the Utah Deaf community, Utah School for the Deaf staff, and students. Max earned recognition as a long-time ecclesiastical leader for his work in the Ogden Branch for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which led to the establishment of new Deaf/ASL units in Utah and beyond.

Max W. Woodbury was born in St. George, Utah, on June 13, 1877. Robert W. Tegeder, a former superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind and an author, noted in his "Utah Loses Its Foremost Educator of the Deaf," article published in "The Utah Eagle," the school's magazine, that during the 1940s, "Max was one of the few educators of the deaf on the west side of the Rocky Mountains who was well known on the east side." Max was president of the Ogden Branch for the Deaf for 51 years while working at the Utah School for the Deaf (USD). Max's accomplishments in the field of deaf education included serving as a USD principal and spiritual leader of the Ogden Branch (The Utah Eagle, January 1974).

C. Roy Cochran, a former USD student and long-time leader of the Ogden Branch, stated that Max began to lose hearing and finally became hard of hearing while attending the University of Utah. He couldn't hear his professor's lecture one day, so he moved to the front row, which drew his professor's attention. His professor advised Max to seek a job at the Utah School for the Deaf (Roy Cochran, personal communication, July 9, 2011). Kenneth L. Kinner, a USD student, and long-time Ogden Branch leader, recalled Max wearing his hearing aid with a wire loop around his head (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, July 9, 2011).

C. Roy Cochran, a former USD student and long-time leader of the Ogden Branch, stated that Max began to lose hearing and finally became hard of hearing while attending the University of Utah. He couldn't hear his professor's lecture one day, so he moved to the front row, which drew his professor's attention. His professor advised Max to seek a job at the Utah School for the Deaf (Roy Cochran, personal communication, July 9, 2011). Kenneth L. Kinner, a USD student, and long-time Ogden Branch leader, recalled Max wearing his hearing aid with a wire loop around his head (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, July 9, 2011).

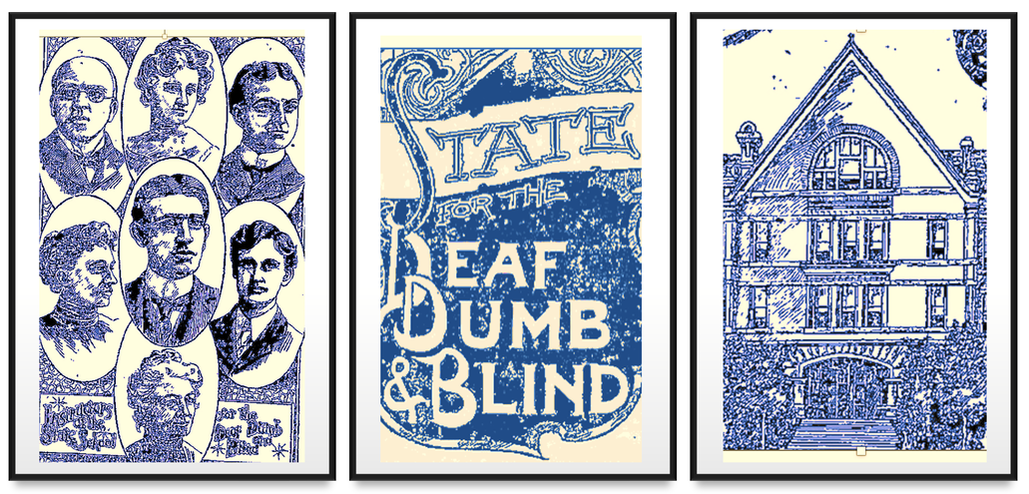

The Utah School for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind, as it was called back then, was featured in the Ogden Daily Standard on December 20, 1902. The staff members were, from top to bottom, L-R: Albert Talage, Catherine King, Elizabeth DeLong, Superintendent Frank M. Driggs (Center), Sarah Whalen, E.S. Henne, and Max W. Woodbury

Max began his teaching career as an assistant superintendent of Sunday School at the Utah School for the Deaf and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on September 1, 1902, the same year he learned sign language (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945; Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf—Compiled February 11, 1992; Roy Cochran, personal communication, July 18, 2011).

In 1907, Max was appointed assistant superintendent of the Ogden 4th Ward Sunday School. Max was promoted to superintendent of the Sunday school in 1911, and Elsie M. Christiansen (Deaf) to assistant superintendent. In 1912, Max and Elsie wrote to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints President Joseph F. Smith, describing the conditions of the Sunday School for the Deaf in the Ogden 4th Ward and requesting that a suitable place of worship be erected solely for the use of the Deaf members (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945).

Another letter followed, with the signatures of many older Deaf members who asked for their place of worship. Furthermore, Max and Elsie met with the Church's Presidency twice to discuss concerns. (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945) The request was granted.

On February 14, 1917, President Smith dedicated the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, and it was established and made an independent branch of the Ogden Stake. Max was sustained as branch president, while Elsie served as branch clerk and secretary (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945; Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf—Compiled February 11, 1992).

Another letter followed, with the signatures of many older Deaf members who asked for their place of worship. Furthermore, Max and Elsie met with the Church's Presidency twice to discuss concerns. (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945) The request was granted.

On February 14, 1917, President Smith dedicated the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, and it was established and made an independent branch of the Ogden Stake. Max was sustained as branch president, while Elsie served as branch clerk and secretary (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945; Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf—Compiled February 11, 1992).

Max supervised 75 boys in the hostel while teaching at USD. Max was a teacher when the Utah Association of the Deaf was formed on June 10th and 11th, 1909, at the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. At the Utah Association of the Deaf's First Triennial Convention on campus, he addressed the audience on "What Other Associations Have Done for Their Respective States?" and briefly discussed the future of the Utah Association of the Deaf (1909 First Convention Minutes; UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963).

During the summers, he pursued his education at Utah State Agricultural College (later renamed Utah State University). He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in June 1915 and a Certificate in School Administration from the same college in 1932 (The Utah Eagle, January 1974).

During the summers, he pursued his education at Utah State Agricultural College (later renamed Utah State University). He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in June 1915 and a Certificate in School Administration from the same college in 1932 (The Utah Eagle, January 1974).

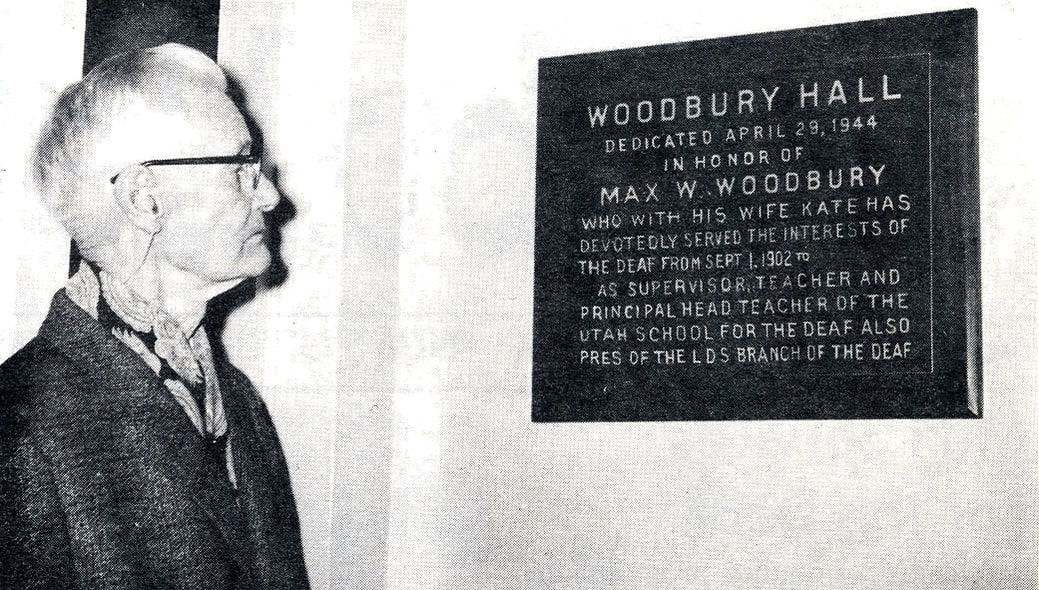

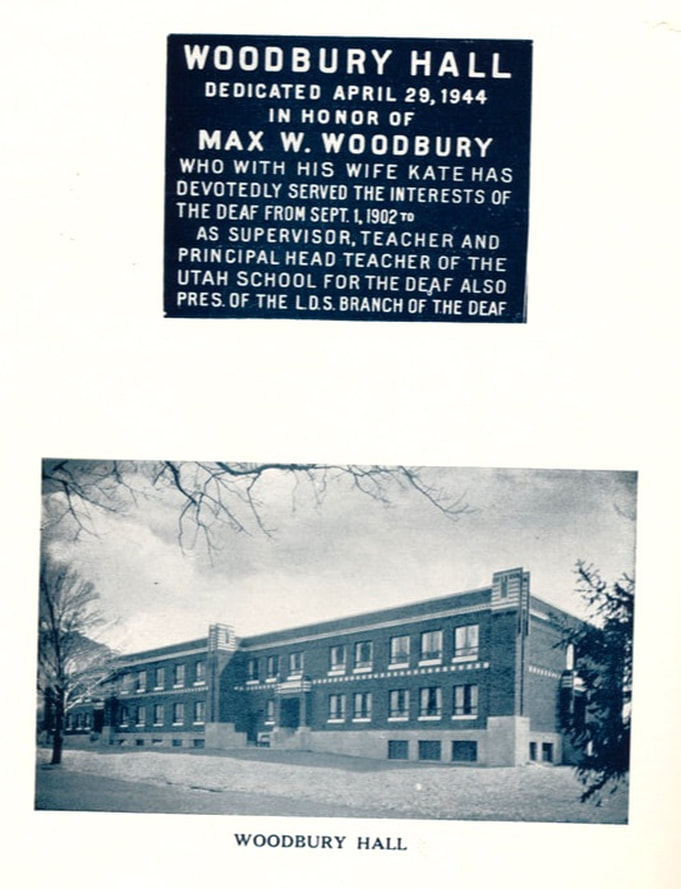

Max became a principal of USD in 1922, a position he held for the next 25 years. He has given the school 45 years of continuous service. After retiring in 1947, he worked as a part-time substitute teacher for five years (The Utah Eagle, January 1974). On April 28, 1944, the boys' dormitory building was named in honor of Max W. Woodbury, who had served the USD and Deaf community for 42 years. The dormitory was officially named "Woodbury Hall" (Pace, 1946, p. 21). Unfortunately, this dormitory building was demolished in the fall of 2012. After Max died in 1973, USD alumni were grateful that he was remembered on the campus of "his school," and they "considered that building as his campus shrine," according to Robert W. Tegeder (The Utah Eagle, January 1974).

According to Robert W. Tegeder, Max found time to contribute to society in addition to his many duties as an educator and church leader. During World War I, he served in the Home Guard; he was a charter member and first president of the Lorin Farr School Parent-Teacher Association; he was secretary-treasurer of the Utah State Teachers' Association; and he was chairman of his party's political precinct for twenty-five years, during which time he served as delegate to many state conventions. He was also heavily involved in the Boy Scout movement. Max also worked as an interpreter at religious functions, weddings, funerals, the courtroom, and other places (The Utah Eagle, January 1974, p. 2).

For 50 years, Max served as president of the Ogden Branch for the Deaf. According to the Winter 1967 UAD Bulletin, he is "believed to have set a record in the church," serving the faculty and students of Utah School for the Deaf and members of the deaf community (p. 1). During his 50 years of service, Max has seen many changes in the branch and USD, where he worked as a teacher, houseparent, and principal for 46 years. According to the Winter 1967 UAD Bulletin, Max "never lost his enthusiasm and faith in the people he has served so well." The Deaf members described him as "straight and trim of figure, with wavy silver hair; his 90 years rest lightly on his shoulders." His sign language remained consistent, clear, and strong. It influenced deaf and hearing people (UAD Bulletin, Winter 1967, p. 1). When Max started teaching at the USD in early 1902, Fred Chambers, Superintendent of Sunday School, invited him to teach Sunday School on weekends. He admitted to Superintendent Chambers that he did not know sign language. Brother Chambers would not accept "no" for an answer. Max accepted and studied sign language (Ogden Branch History).

Members who served under President Woodbury became leaders in the Salt Lake Valley Branch for the Deaf, which had 286 members, the Los Angeles Branch for the Deaf, which had 225 members, and a small new branch in San Jose, California. At the time, another branch was planned for Provo, Utah (The Ogden Standard Examiner, February 4, 1967). Max earned recognition as a long-time ecclesiastical leader for his work in the Ogden Branch for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which led to the establishment of new Deaf/ASL units in Utah and beyond.

President Woodbury was released from the position he had held for 51 years a year later, in February 1968, at the age of 91, during a special program at the sacrament meeting led by a new stake president, Gunn McKay (The Ogden Standard Examiner, February 4, 1967; UAD Bulletin, Winter 1967).

President Woodbury was released from the position he had held for 51 years a year later, in February 1968, at the age of 91, during a special program at the sacrament meeting led by a new stake president, Gunn McKay (The Ogden Standard Examiner, February 4, 1967; UAD Bulletin, Winter 1967).

Max married Kate Forsha on September 10, 1901, and they celebrated their 72nd wedding anniversary on September 10, 1973. They had one son, Max S. Woodbury of Indianapolis, and one daughter, Miriam Woodbury of Ogden (she, like her father, taught at USD for several years before retiring in the 1970s). Max passed away on December 29, 1973, at 96, in Ogden, Utah (R.W.T., The Utah Eagle, January 1974). According to Robert W. Tegeder, "Max was the type of educator and person who could serve well as a model for all modern-day educators and society in general," and "he was also a champion for deaf people everywhere" (The Utah Eagle, January 1974).

After Max died in 1973, Robert W. Tegeder wrote, "of those forty-five years, he [Max] was devoted to the education of the deaf at the Utah School for the Deaf, the institution that he so ably served with such great distinction and devotion as teacher, teacher-supervising teacher, and finally as teacher-principal" (The Utah Eagle, January 1974, p. 1).

According to Robert W. Tegeder, Max was a champion for Deaf people everywhere. Excerpts from some Deaf people who wrote what they recalled about Max for the January 1974 Utah Eagle magazine are as follows:

According to Robert W. Tegeder, Max was a champion for Deaf people everywhere. Excerpts from some Deaf people who wrote what they recalled about Max for the January 1974 Utah Eagle magazine are as follows:

I REMEMBER MAX W. WOODBURY…

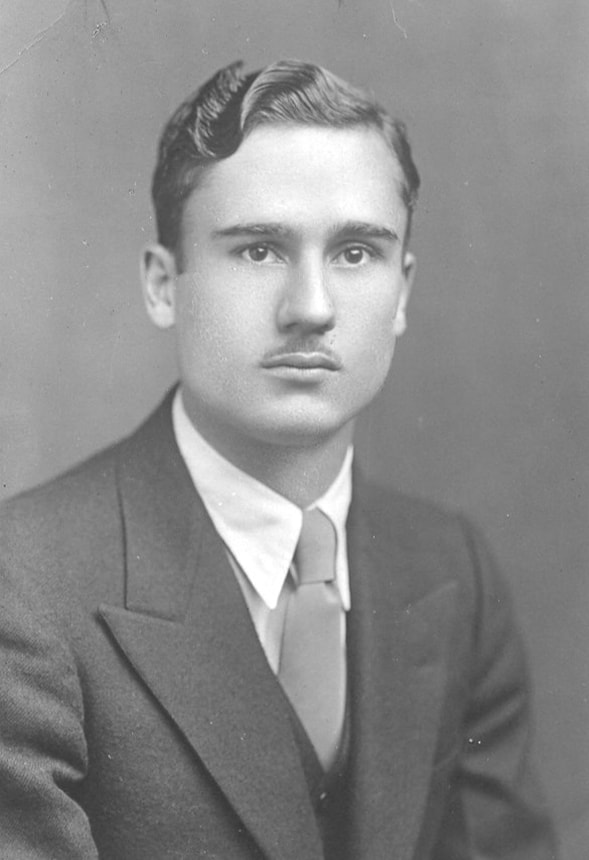

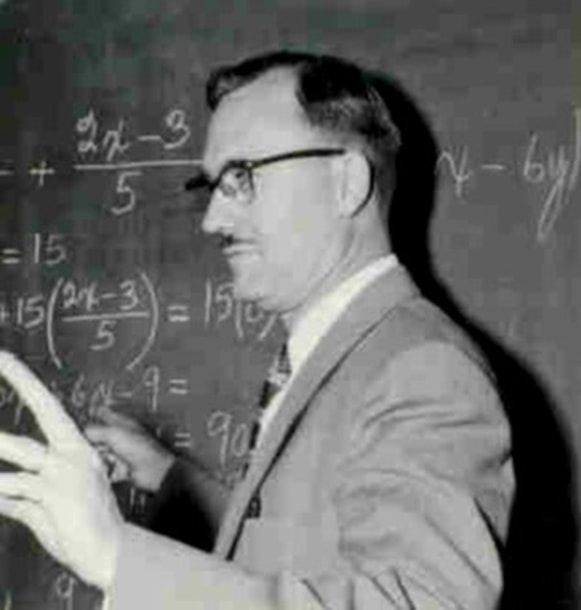

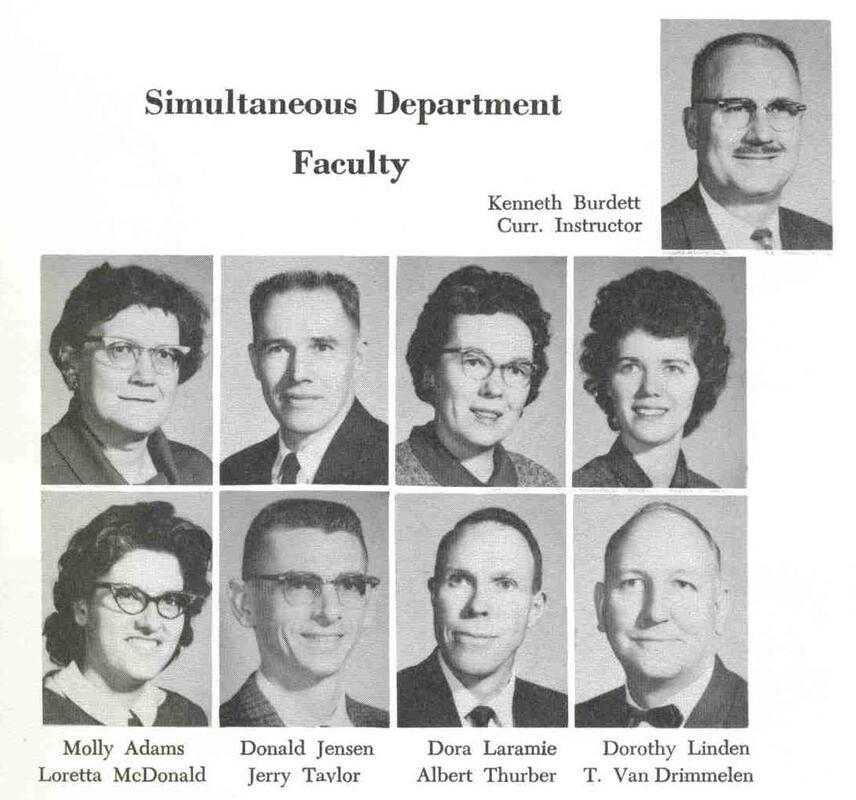

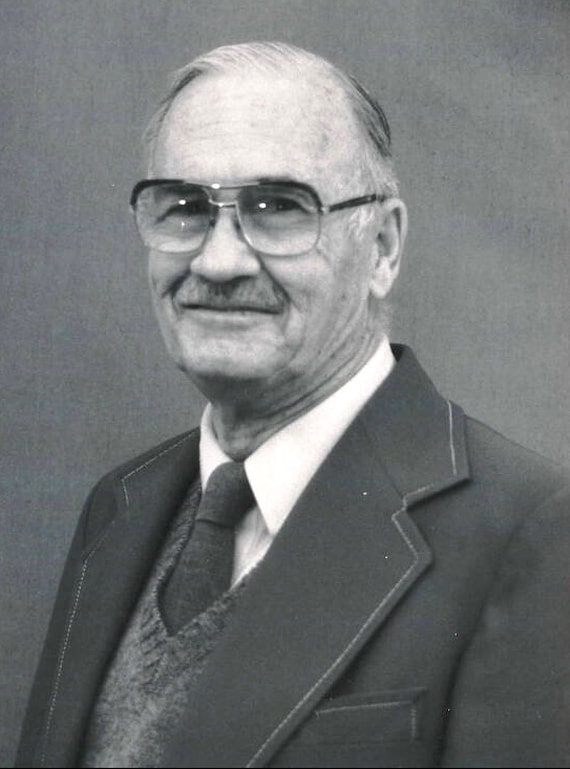

I had known Brother Max W. Woodbury for over fifty years. I was with him as a student and later as a teacher in the Utah School for the Deaf as well as the Latter Day Saints Branch for the Deaf. All the deaf people in Utah looked up to Brother Woodbury as a great man who served not because a task had been assigned, but one of the desires of his heart. By the measure he achieved true greatness. He never flinched from what was right and just and his values were high. Kenneth C. Burdett, Curriculum Coordinator of the Total Communication Division, Utah School for he Deaf (R.W.T., The Utah Eagle, January 1974, p. 1-2).

On behalf of the members of the Branch for the Deaf, we pay our last tribute to resident Max W. Woodbury. We feel deeply the loss of a fine dedicated teacher and spiritual leader who taught us a philosophy of life that helps us meet the challenges of this world. The gospel of Jesus Christ, which he taught us, will make us better men and women and help us to receive joy and happiness in our lives.

No man that we have known has ever lived a more useful life of service to deaf people than President Max W. Woodbury. His untiring service in furthering our education and religion was greatly appreciated. It is our desire and responsibility to so live that we will ever reflect credit to his sincere efforts. We will never forget his kindness, fatherly advice and love shown to us. He leaves with us the memory of his fine leadership and sweet personality. He was a man of superior courage, one we have loved and respected during the years we have spent together.

Ogden LDS Branch for the Deaf

Kenneth L. Kinner, Branch President

C. Roy Cochran, First Counselor

W. Ronald Johnson, Second Counselor

No man that we have known has ever lived a more useful life of service to deaf people than President Max W. Woodbury. His untiring service in furthering our education and religion was greatly appreciated. It is our desire and responsibility to so live that we will ever reflect credit to his sincere efforts. We will never forget his kindness, fatherly advice and love shown to us. He leaves with us the memory of his fine leadership and sweet personality. He was a man of superior courage, one we have loved and respected during the years we have spent together.

Ogden LDS Branch for the Deaf

Kenneth L. Kinner, Branch President

C. Roy Cochran, First Counselor

W. Ronald Johnson, Second Counselor

Notes

C. Roy Cochran, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, July 9, 2011.

Kenneth L. Kinner, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, July 9, 2011.

Kenneth L. Kinner, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, July 9, 2011.

References

History of the Ogden Branch.

Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf – Compiled February 11, 1992.

Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941 – 1945, p. 123 – 134.

Tegeder, Robert W. "Utah Loses its Foremost Educator of the Deaf." The Utah Eagle (January 1974): 1-2.

"Two Events Will Honor Deaf Branch President." Ogden Standard-Examiner, February 4, 1967.

UAD's First Convention Minutes: 1909 Minutes.

"UAD's Unveiling Ceremony at Ogden Branch." UAD Bulletin, Vol. 111, No. 3 (October 1976): 2.

Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf – Compiled February 11, 1992.

Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941 – 1945, p. 123 – 134.

Tegeder, Robert W. "Utah Loses its Foremost Educator of the Deaf." The Utah Eagle (January 1974): 1-2.

"Two Events Will Honor Deaf Branch President." Ogden Standard-Examiner, February 4, 1967.

UAD's First Convention Minutes: 1909 Minutes.

"UAD's Unveiling Ceremony at Ogden Branch." UAD Bulletin, Vol. 111, No. 3 (October 1976): 2.

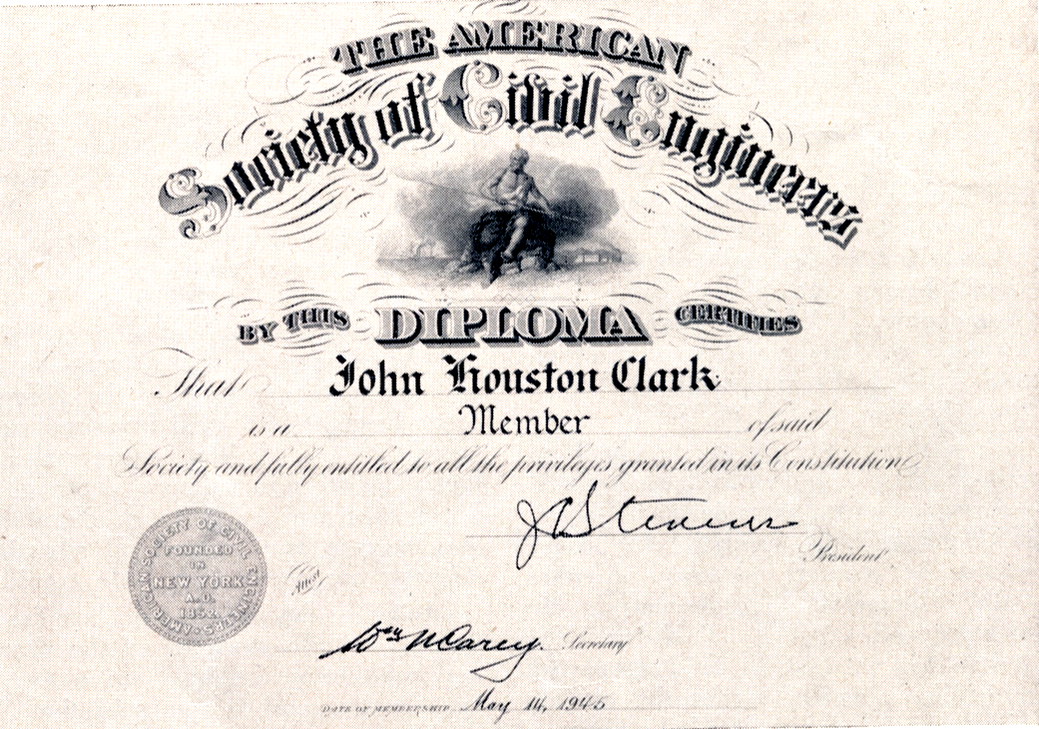

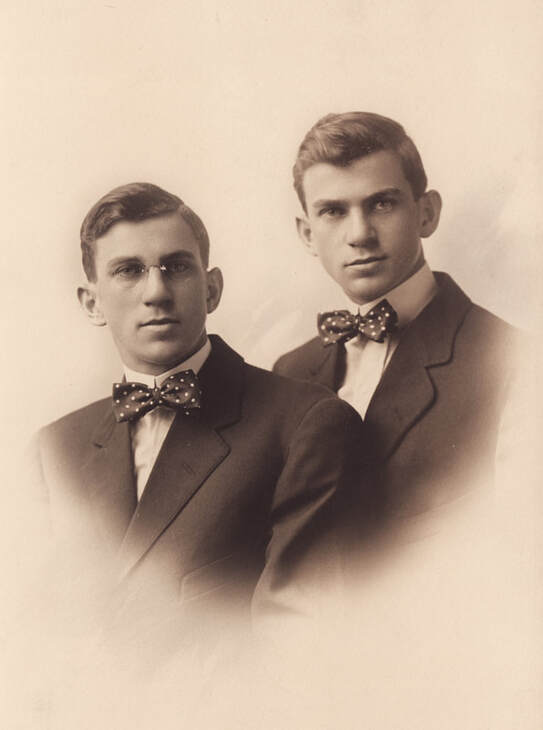

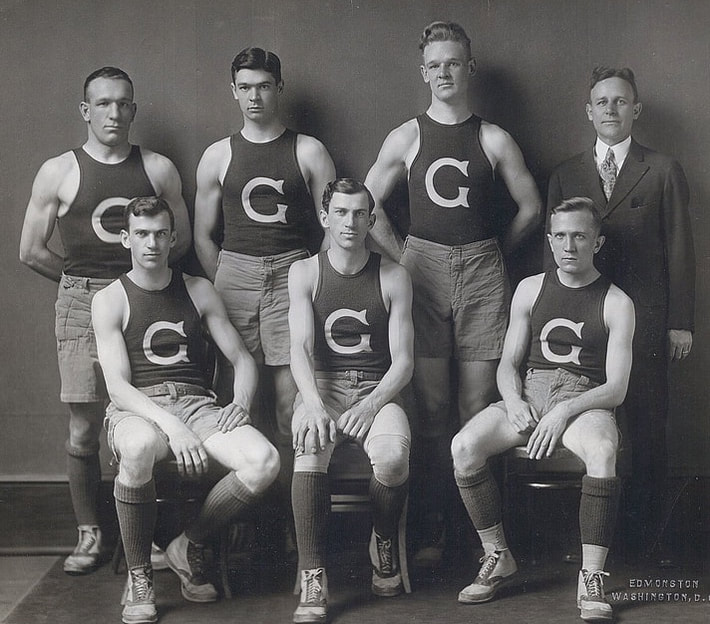

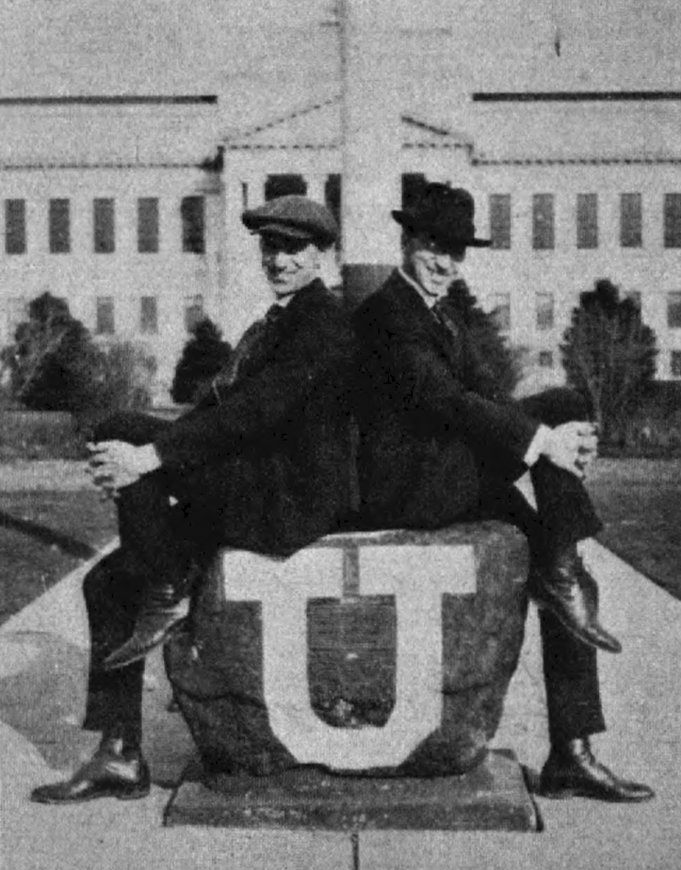

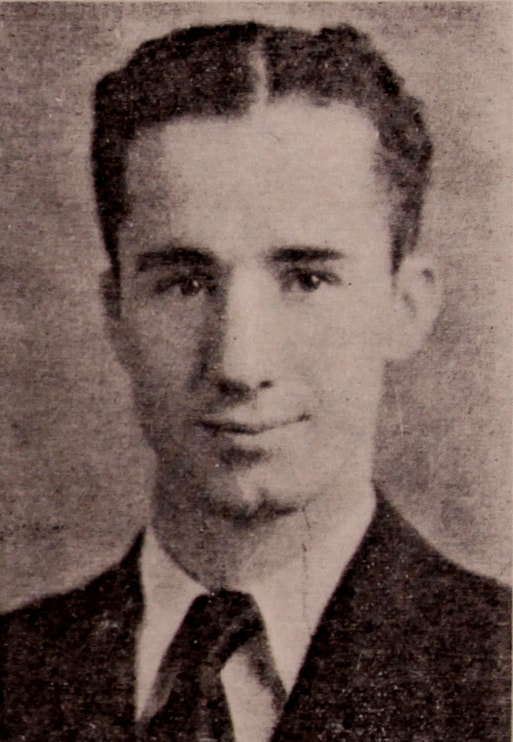

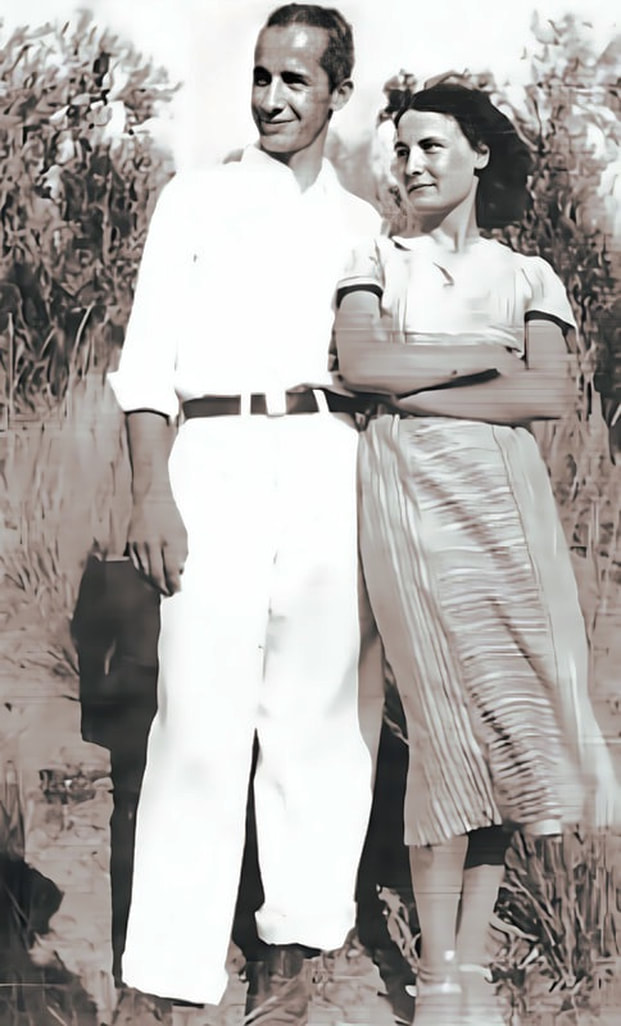

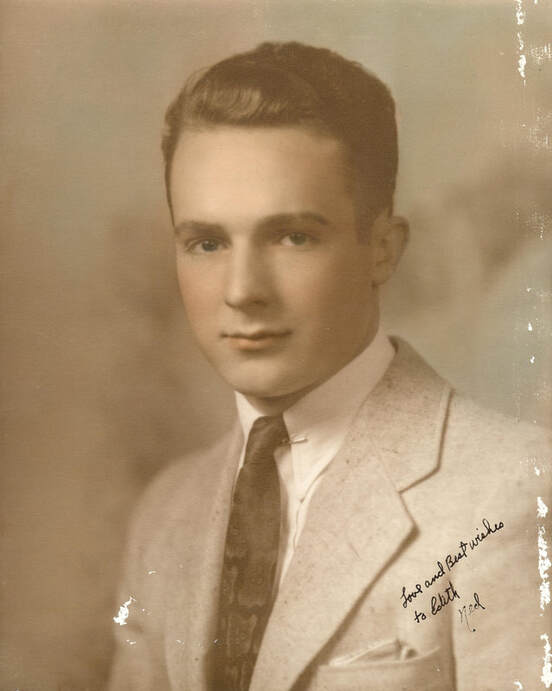

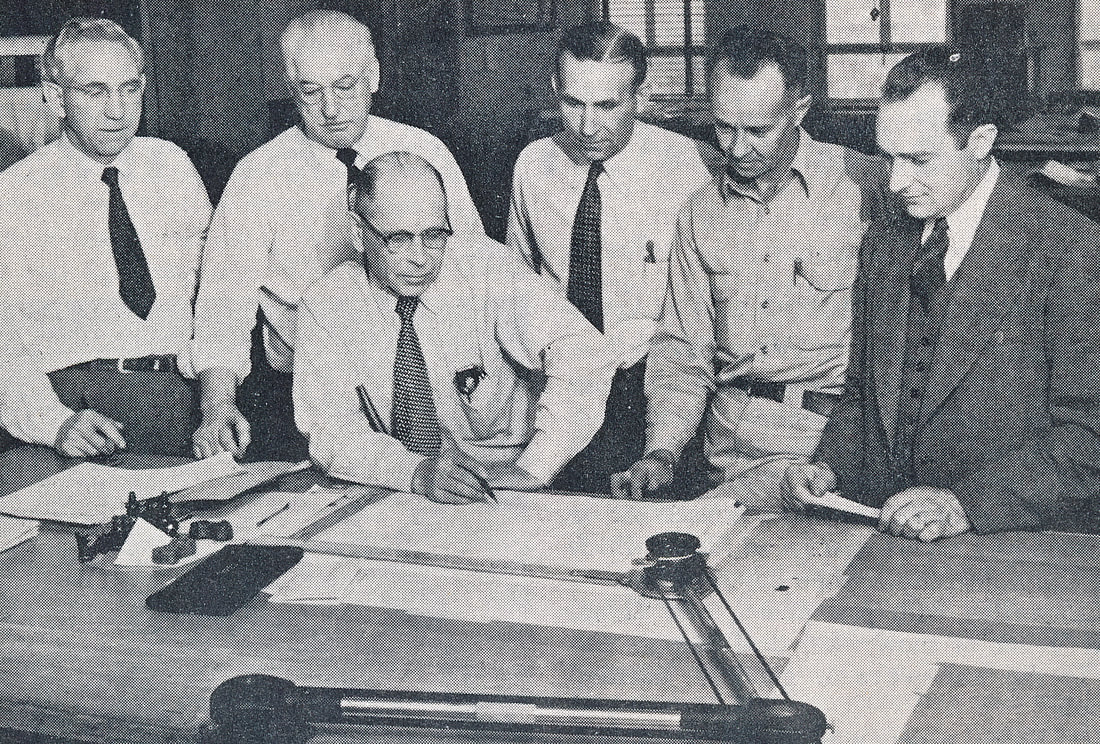

John H. Clark, Conservation Leader

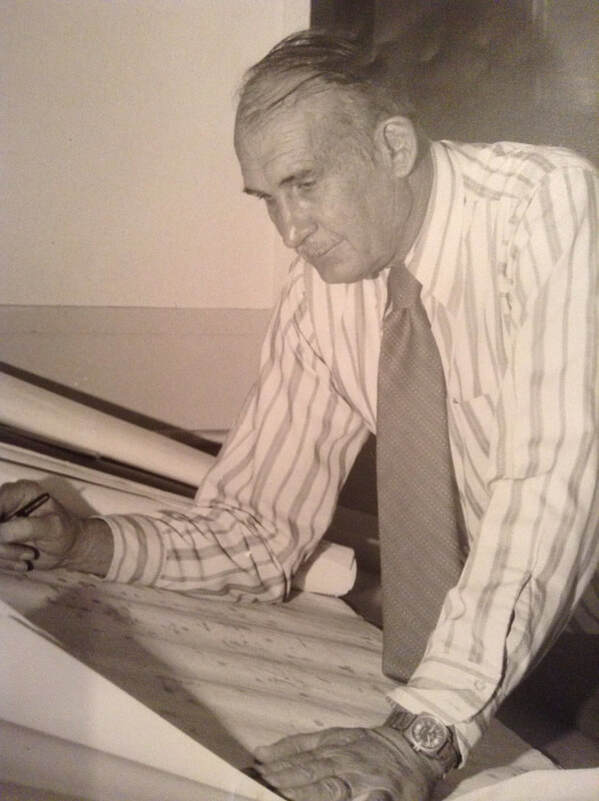

During John H. Clark's time at the Utah School for the Deaf, he was one of the editors of the school newspaper, The Eaglet. Upon graduation, he and his cousin, Elizabeth DeLong, were the first students to enter Gallaudet College in 1897. During his senior year at Gallaudet, he wrote stories and was elected editor-in-chief of Buff and Blue. He graduated from Gallaudet College in 1902 with a major in mathematics, which sparked his interest in field surveying, where he was tutored by then Professor Percival Hall, the 2nd Gallaudet president. After obtaining his Bachelor of Science from Gallaudet College in 1902, John returned to Utah to continue his civil engineering and field surveying education. Local, state, and city officials learned about his work and offered him jobs in Southern Utah and nearby states. He surveyed and oversaw water systems, hydroelectric plants, bridges, and roadways in Southern Utah and nearby states, which led him to form his Clark Construction Company. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt praised him for his dedication to protecting the conservation of natural resources. In June 1924, Gallaudet College awarded the honorary degree of Master of Science to John H. for his civil engineering and surveying expertise.

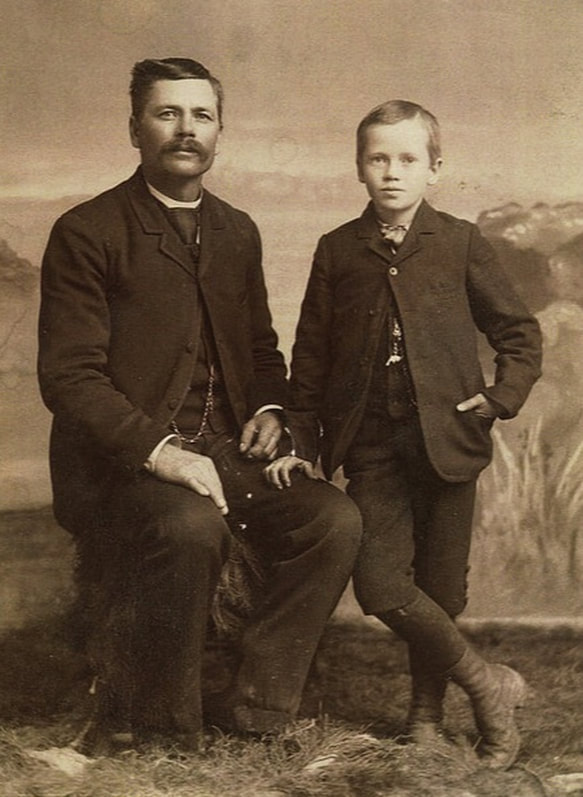

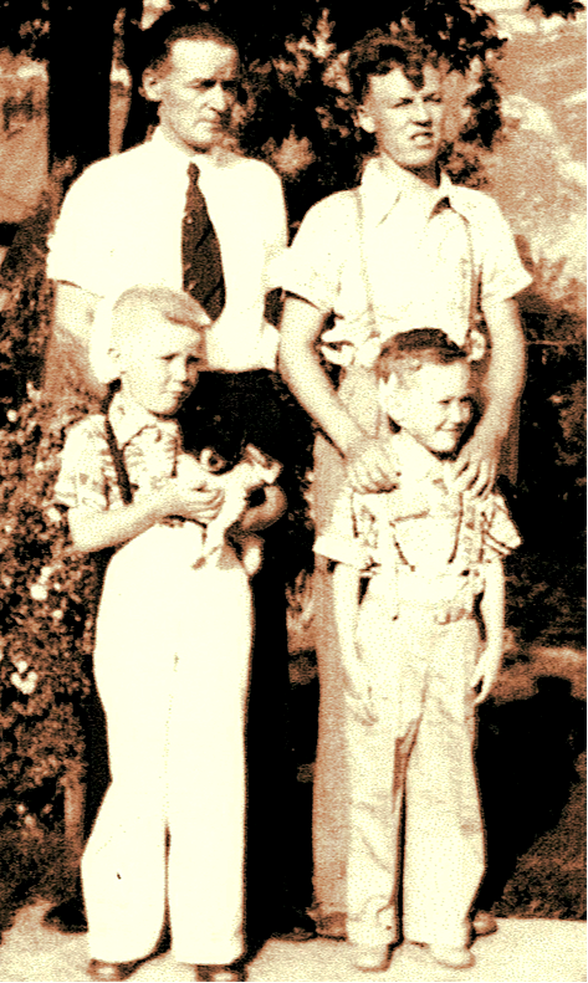

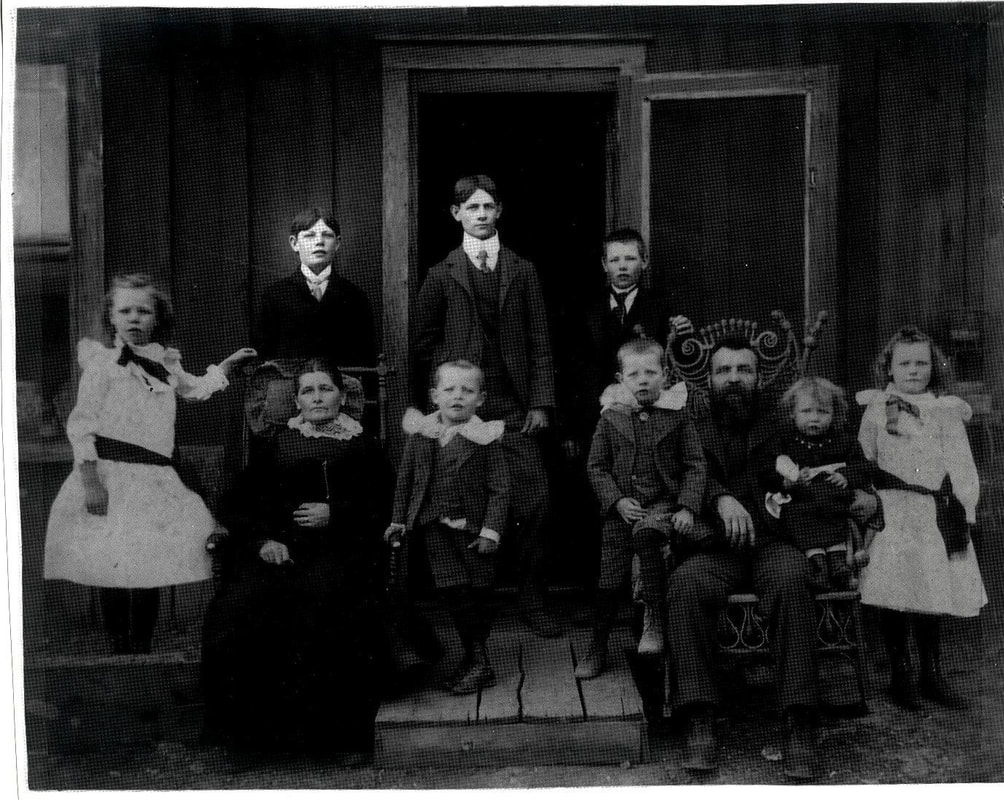

John Houston Clark, commonly known as John H., was born hearing in Panguitch, Utah, on May 17, 1880, to Riley Garner Clark and Margaret Houston. Together, they had ten children: Arthur, Riley Garner III, John Houston, James Cecil, Joseph Clark, Ernest Clark, Margaret Fern, Ivy Amanda, Stanley M., and Elden Dewey.

When John H. was ten, his two brothers, Arthur and Ernest, died of spinal meningitis, leaving him completely deaf. His life hung in the balance for several days while in a coma. Following his recovery, he was homeschooled for one year. In 1891, at the age of 11, he enrolled in the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) housed at the University of Deseret (later renamed the University of Utah) in Salt Lake City, Utah, where his cousin, Elizabeth DeLong, the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, who became deaf at the age of five, was also attended. He excelled in all his classes. He was also a brilliant debater in the Park Literary Society (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956; Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008).

When John H. was ten, his two brothers, Arthur and Ernest, died of spinal meningitis, leaving him completely deaf. His life hung in the balance for several days while in a coma. Following his recovery, he was homeschooled for one year. In 1891, at the age of 11, he enrolled in the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) housed at the University of Deseret (later renamed the University of Utah) in Salt Lake City, Utah, where his cousin, Elizabeth DeLong, the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, who became deaf at the age of five, was also attended. He excelled in all his classes. He was also a brilliant debater in the Park Literary Society (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956; Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008).

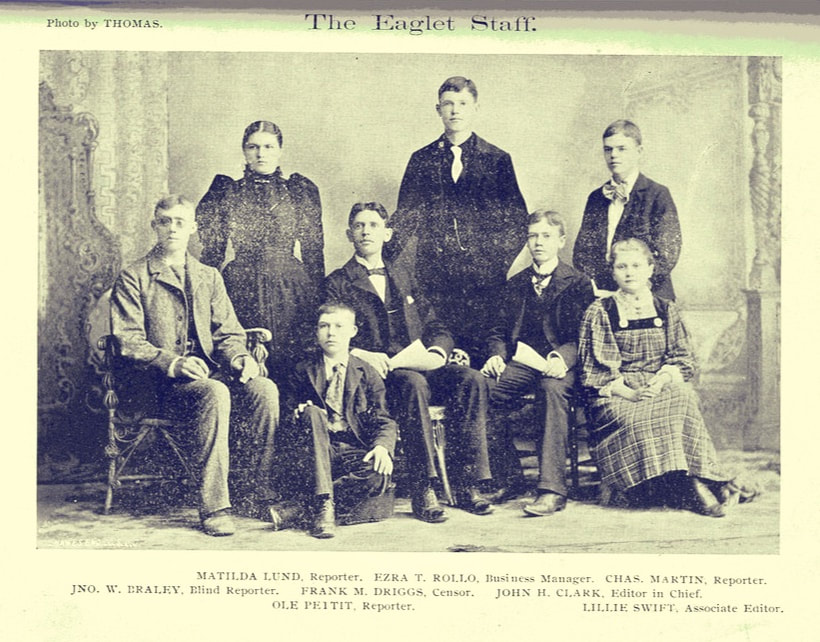

Dr. Thomas C. Clark, his son, recalls his father being registered as "student #70 on September 12, 1891." During his stay at the institution, John H. was a student newspaper editor for The Eaglet (Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008). John H. and Libbie were storytellers at the gathering in 1893 as members of the Park Literacy Society (Banks & Banks).

John H. was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While the Utah School for the Deaf was located at the University of Deseret, John H. was most likely one of the first Deaf Mute Sunday School students of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (The Daily Enquirer, February 11, 1892). When USD moved to Ogden in 1896, he continued to attend and even teach Sunday School in the old Ogden Fourth Ward Amusement Hall (Deseret News, November 21, 1896).

While a student at the Utah School for the Deaf, John H.'s teachers pushed him to apply to Gallaudet College. In the fall of 1897, he entered Gallaudet College after passing all eight required written examinations (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956). John H. and Libbie were the only two students to graduate from USD on June 8, 1897 (The Ogden Standard, May 8, 1897). It appears that they graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1897 in Ogden, Utah, a year after the school relocated to this area in 1896.

John H. and Libbie were also the first students from Utah to enroll at Gallaudet College in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1897. On September 15, 1897, Frank M. Driggs, superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf and the Blind, accompanied them by train to their first year at Gallaudet for a four-year college. At the same time, Frank was enrolled in a one-year teacher training program at Gallaudet College (The Ogden Examiner-Standard, September 15, 1897). If he hadn't been present, John H. and Libbie would not have had the opportunity to travel so far.

John H. and Libbie were also the first students from Utah to enroll at Gallaudet College in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1897. On September 15, 1897, Frank M. Driggs, superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf and the Blind, accompanied them by train to their first year at Gallaudet for a four-year college. At the same time, Frank was enrolled in a one-year teacher training program at Gallaudet College (The Ogden Examiner-Standard, September 15, 1897). If he hadn't been present, John H. and Libbie would not have had the opportunity to travel so far.

John H. was a good student at Gallaudet College and dressed well. As small in stature, John H. did not participate in sports except tennis and his regular gymnasium routine (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956). He was the Gallaudet football team's assistant coach (The Silent Worker, December 1900).

John H.'s proficiency in English led to his writing stories and numerous articles for The Buff and Blue, the student magazine at Gallaudet College. During his senior year, he was elected editor-in-chief of the publication (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956). His cousin, Libbie, also a senior, was named associate editor (The Ogden Examiner-Standard, June 19, 1901; Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008). According to an Ogden Standard article from 1901, "to be elected editor-in-chief of the college paper has always been considered one of the highest honors."

While a junior at Gallaudet College, John H. was picked to deliver the senior farewell address to the entire school. His address was clear, elegant, and powerful (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956).

At Gallaudet College, John H. also excelled in mathematics, which sparked his interest in field surveying, where he was tutored by then-Professor Percival Hall, the 2nd Gallaudet president, a Harvard graduate, and the son of a famous astronomer, Asaph Hall (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956; Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008).

According to "The Deseret Weekly" article, being a Mormon boy at that college [Gallaudet] and being so far away from home was new to John H. He defended his Mormon beliefs as a sophomore in this article after a respected Gallaudet professor made false claims about Mormon teachings. The professor thought Brigham Young had given the order for the infamous Mountain Meadows Massacre, presumably at John Doyle Lee's request. "It is astounding how little most eastern people know about our faith," John H. wrote in The Deseret Weekly on January 15, 1898. [The author's spouse, Duane Lee Kinner, is the direct descendant of John Doyle Lee, who was convicted as a mass murderer for his involvement in the Mountain Meadows massacre, sentenced to death, and executed in 1877.]

John H.'s proficiency in English led to his writing stories and numerous articles for The Buff and Blue, the student magazine at Gallaudet College. During his senior year, he was elected editor-in-chief of the publication (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956). His cousin, Libbie, also a senior, was named associate editor (The Ogden Examiner-Standard, June 19, 1901; Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008). According to an Ogden Standard article from 1901, "to be elected editor-in-chief of the college paper has always been considered one of the highest honors."

While a junior at Gallaudet College, John H. was picked to deliver the senior farewell address to the entire school. His address was clear, elegant, and powerful (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956).

At Gallaudet College, John H. also excelled in mathematics, which sparked his interest in field surveying, where he was tutored by then-Professor Percival Hall, the 2nd Gallaudet president, a Harvard graduate, and the son of a famous astronomer, Asaph Hall (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956; Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008).

According to "The Deseret Weekly" article, being a Mormon boy at that college [Gallaudet] and being so far away from home was new to John H. He defended his Mormon beliefs as a sophomore in this article after a respected Gallaudet professor made false claims about Mormon teachings. The professor thought Brigham Young had given the order for the infamous Mountain Meadows Massacre, presumably at John Doyle Lee's request. "It is astounding how little most eastern people know about our faith," John H. wrote in The Deseret Weekly on January 15, 1898. [The author's spouse, Duane Lee Kinner, is the direct descendant of John Doyle Lee, who was convicted as a mass murderer for his involvement in the Mountain Meadows massacre, sentenced to death, and executed in 1877.]

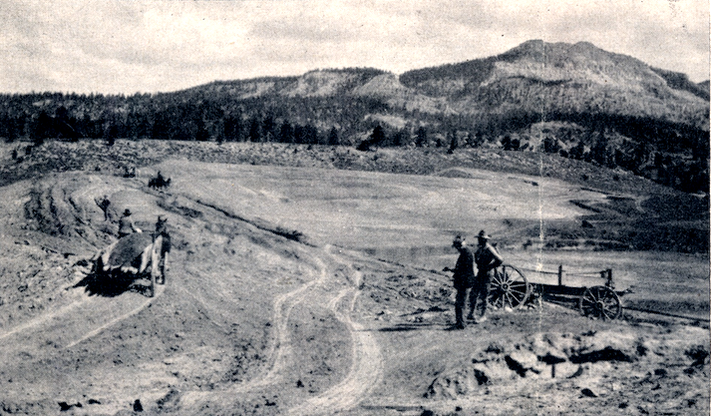

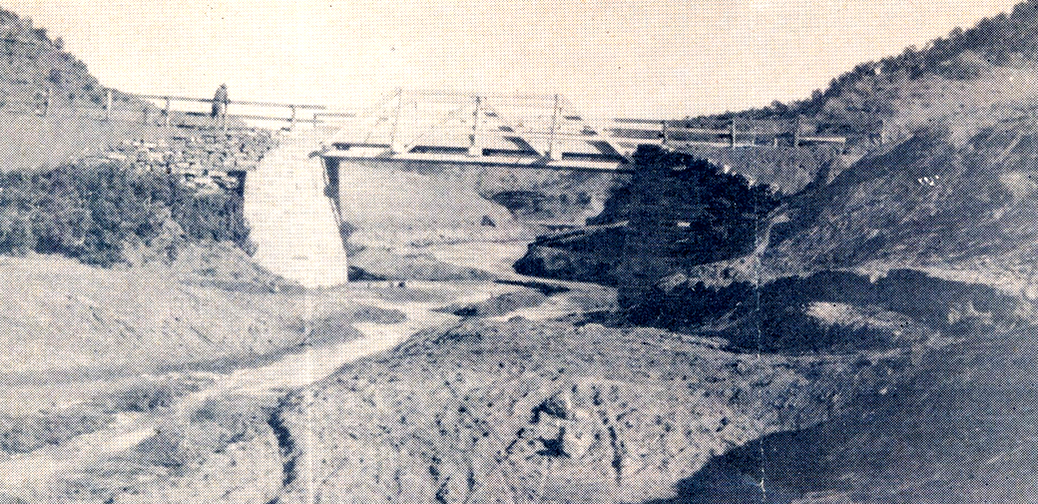

After obtaining his Bachelor of Science from Gallaudet College in 1902, John H. returned to Utah to continue his civil engineering and field surveying education. Local, state, and city officials learned about his work and offered him jobs in Southern Utah and nearby states. He surveyed and oversaw water systems, hydroelectric plants, bridges, and roadways for these. Locals and government officials praised him for his exceptional skill and knowledge of the different areas, difficult terrain, and geologic formations. His hearing loss didn't get in the way of him doing his job every day. He was always at ease and tackled any situation, easily getting through it (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956).

John H.'s career began in 1904 in the Forest Service of Utah. He did surveying and supervising in the Grand Canyon and Kaibab Forest. In 1907, he made a map of Idaho's Snake River. John claimed to be the first white person to walk through the wild parts of what is now called "Hell's Canyon." At the time, his group went unnoticed; it was thought that everyone might have died or been lost for good. Fortunately, everything worked out. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt later praised him for his dedication to protecting the conservation of natural resources (Runde, The Silent Worker, May 1956).

John H. was a member of the American Military Engineers and a licensed professional engineer and land surveyor in Utah and New Mexico. He was appointed a surveyor by the United States government for some specific work in southern Utah in 1906. His promotion was based on his previous surveying work for Uncle Sam (The Silent Worker, June 1906).