The History of

Utah Deaf Sports

Utah Deaf Sports

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2014

Updated in 2024

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2014

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

The Utah School for the Deaf (USD) has been providing sports programs since the early 1900s, just like other state schools for the deaf around the country (Roberts, 1994). Sports have always been an integral part of the Utah Deaf community, as well as the national Deaf community.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading 'The History of Utah Sports' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading 'The History of Utah Sports' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Utah Deaf Sports Organizations

The Utah School for the Deaf (USD) has offered athletic programs since the early 1900s. Sports play a significant role in both the Utah and national Deaf communities. Our community has a rich history of participating in sports, marked by numerous achievements and successes. Participation in sports can aid in developing physical, social, and leadership skills. Through sports, participants can improve their ability to interact with people, communicate effectively, and work as a team. Additionally, sports can help develop strategic thinking and problem-solving skills. Above all, sports build confidence, and winning a game gives athletes a sense of accomplishment, further enhancing their confidence.

The following six sections comprise: 1. Athletic Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf; 2. Utah Athletic Club for the Deaf; 3. Golden Spike Athletic Club for the Deaf; and 4. Wasatch Golf Association for the Deaf. The 16th Winter Deaflympics in Utah, as well as Dennis Platt as torchbearer, are highlighted below.

The following six sections comprise: 1. Athletic Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf; 2. Utah Athletic Club for the Deaf; 3. Golden Spike Athletic Club for the Deaf; and 4. Wasatch Golf Association for the Deaf. The 16th Winter Deaflympics in Utah, as well as Dennis Platt as torchbearer, are highlighted below.

The Athletic Programs at the

Utah School for the Deaf

Utah School for the Deaf

As stated above, the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) has offered sports programs since the early 1900s, as have other state schools for the deaf around the country (Roberts, 1994). Sports have always been an important element of the Deaf community in Utah and the national Deaf community.

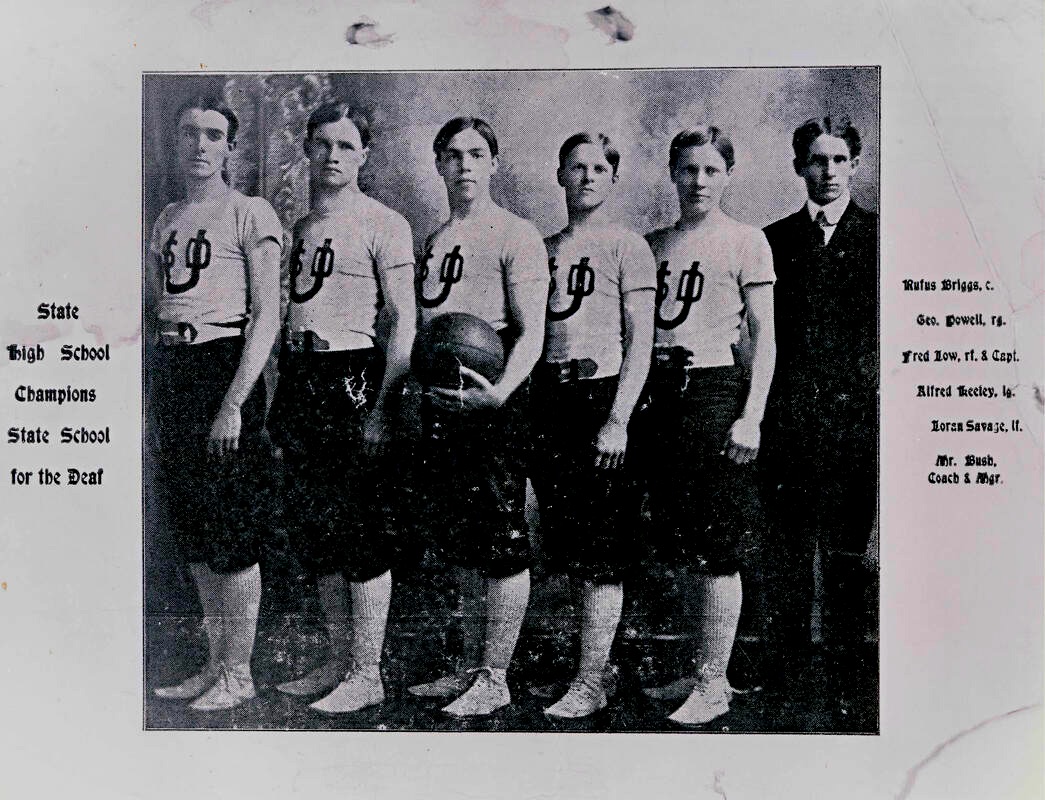

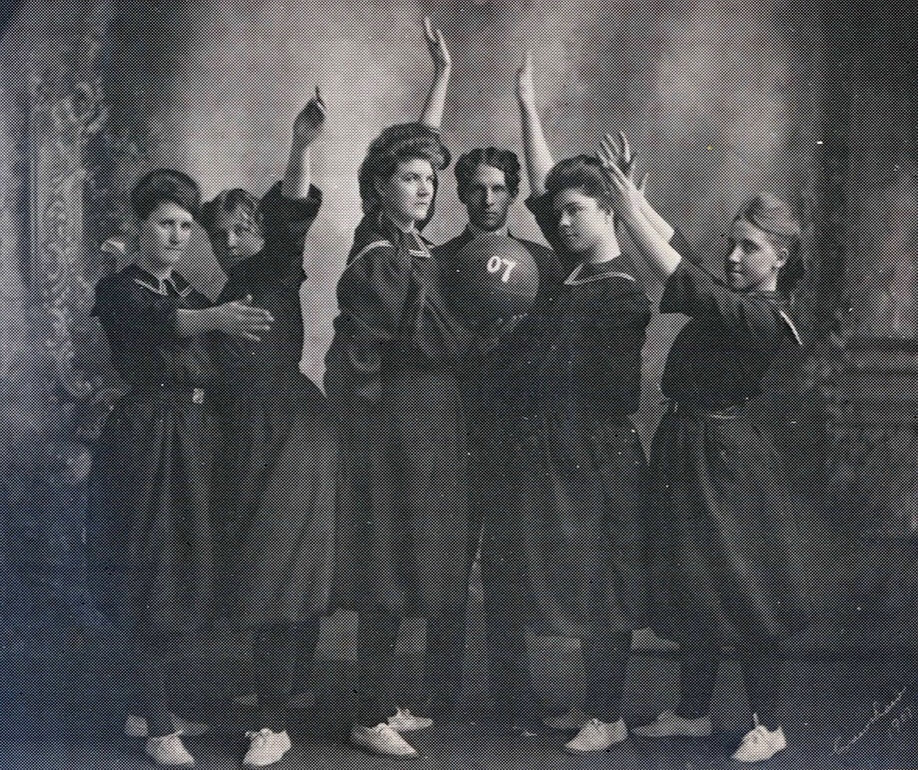

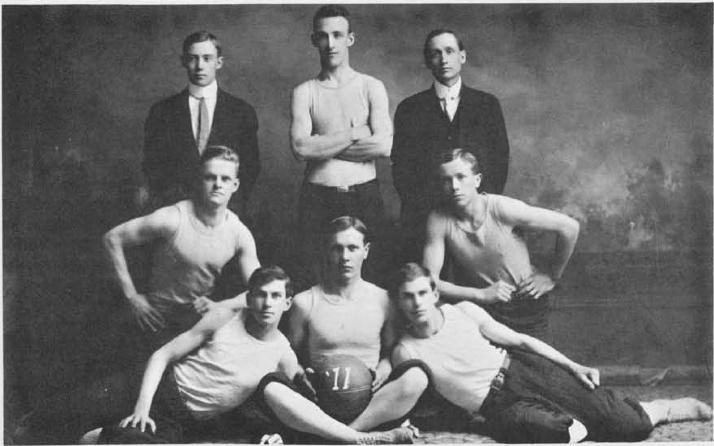

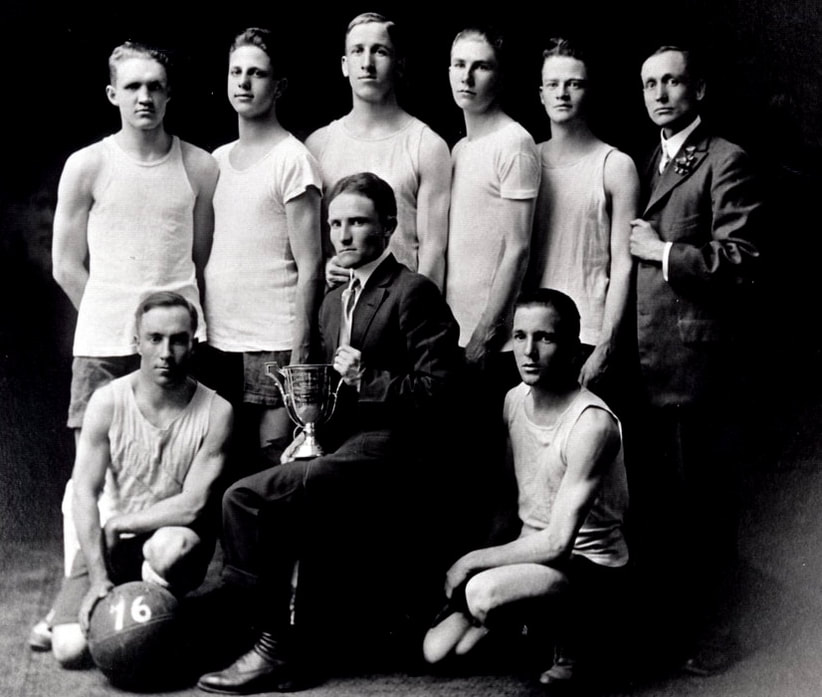

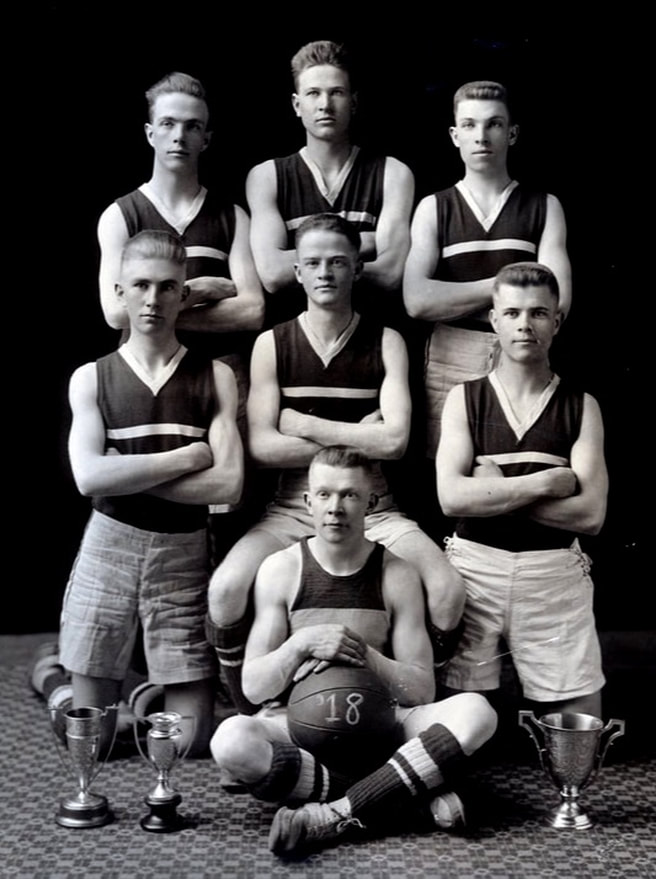

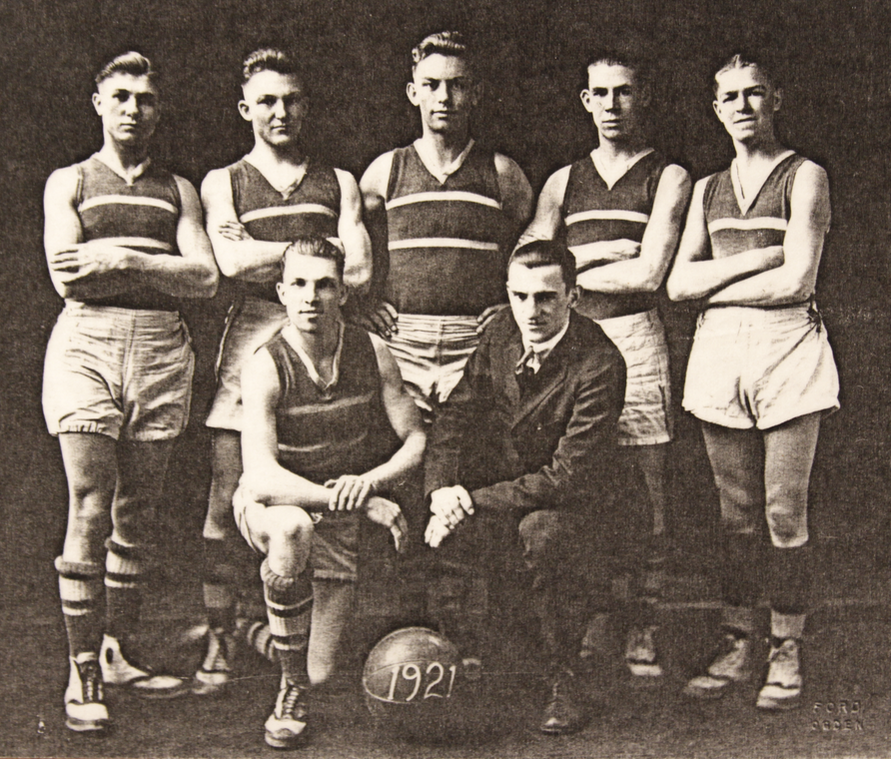

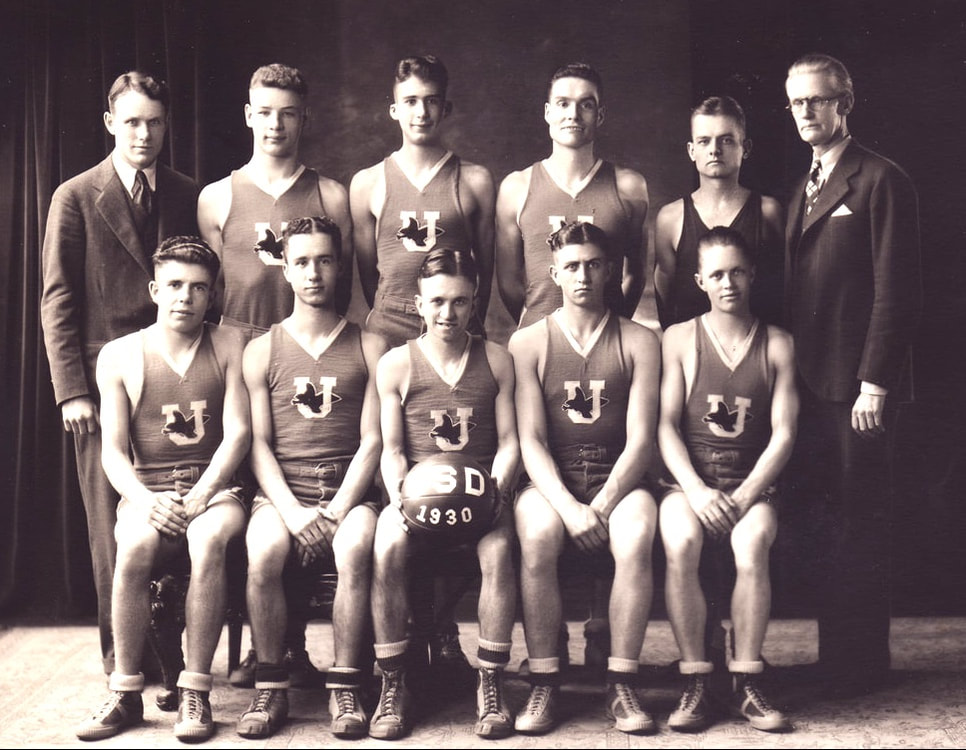

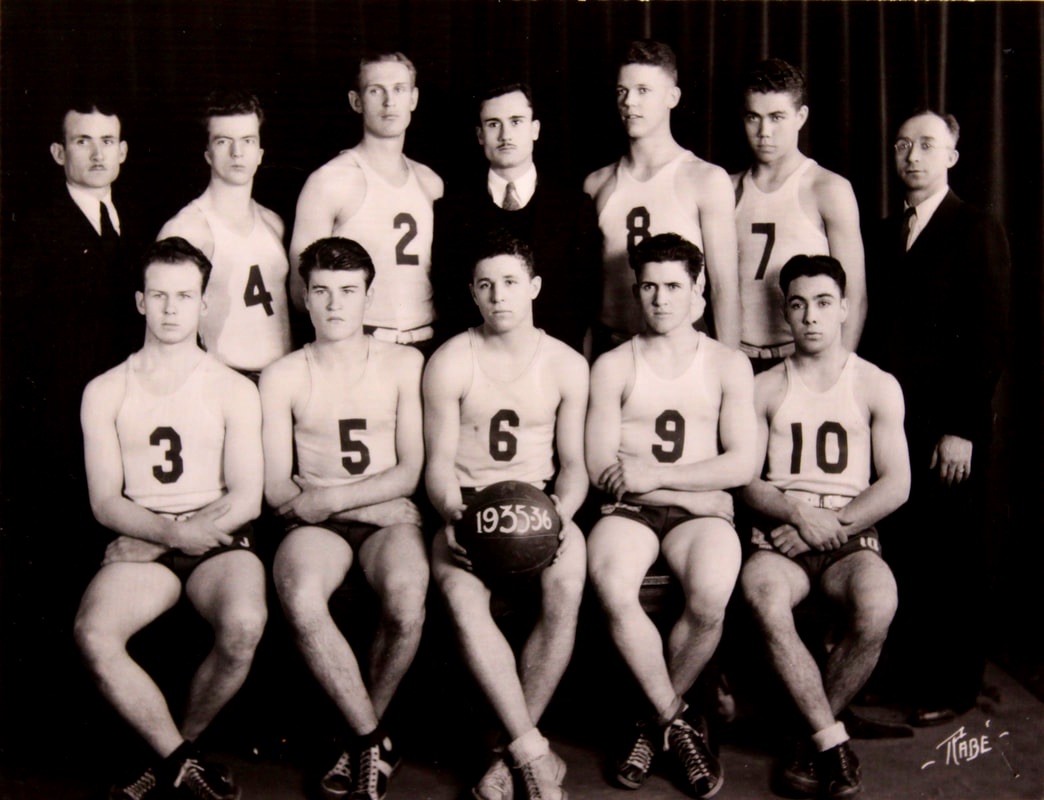

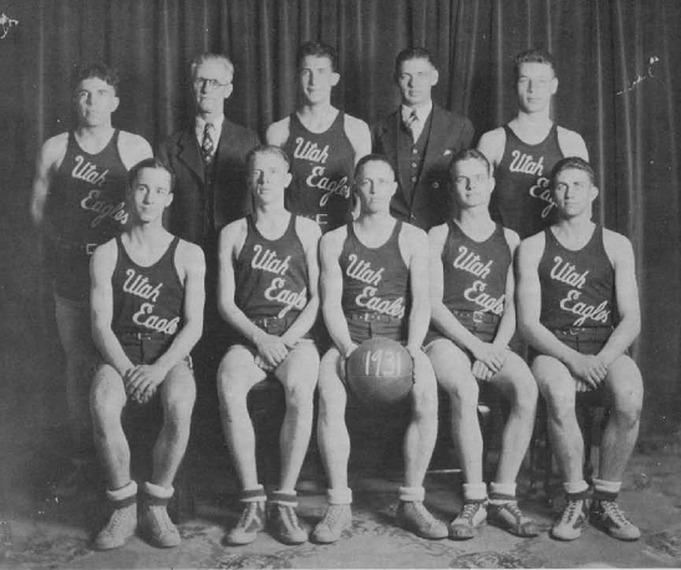

In 1921, Arthur W. Wenger, a sports enthusiast and a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1913, founded the Arthur Wenger Athletic Association. Wenger observed that the Utah School for the Deaf had students with mixed abilities. Some were too aggressive or clumsy, while others were too timid. Arthur believed that playing sports helped these students learn to interact with each other and, in turn, softened their rough edges. Arthur mentioned that some students came from fields and found it hard to catch a ball, but after learning to play sports, they could do so. The Utah School for the Deaf taught various sports, including baseball, volleyball, soccer, basketball, and medicine ball, as shown in the photos below (Wenger, Silent Worker, January 1921).

In 1921, Arthur W. Wenger, a sports enthusiast and a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1913, founded the Arthur Wenger Athletic Association. Wenger observed that the Utah School for the Deaf had students with mixed abilities. Some were too aggressive or clumsy, while others were too timid. Arthur believed that playing sports helped these students learn to interact with each other and, in turn, softened their rough edges. Arthur mentioned that some students came from fields and found it hard to catch a ball, but after learning to play sports, they could do so. The Utah School for the Deaf taught various sports, including baseball, volleyball, soccer, basketball, and medicine ball, as shown in the photos below (Wenger, Silent Worker, January 1921).

Arthur encouraged athletic programs that included games that presented unexpected situations that required players to think and move in time with the rhythm of the games, much like a piano and not a music box. This instilled in the students a sense of balance and composure throughout the year (Wenger, Silent Worker, January 1921, p. 3).

The Sports Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf

from 1903 to 1957

from 1903 to 1957

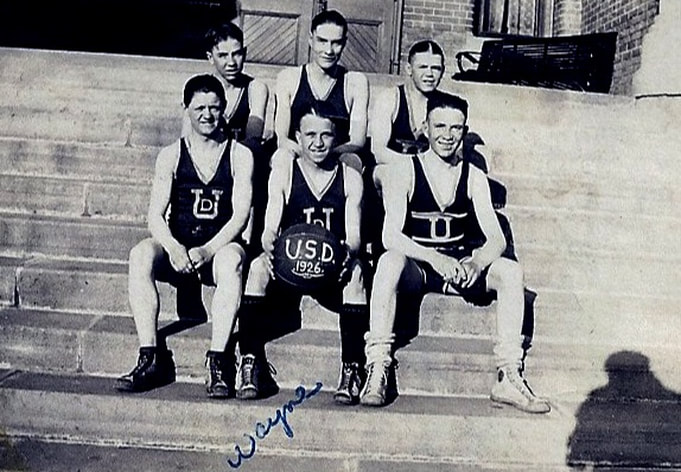

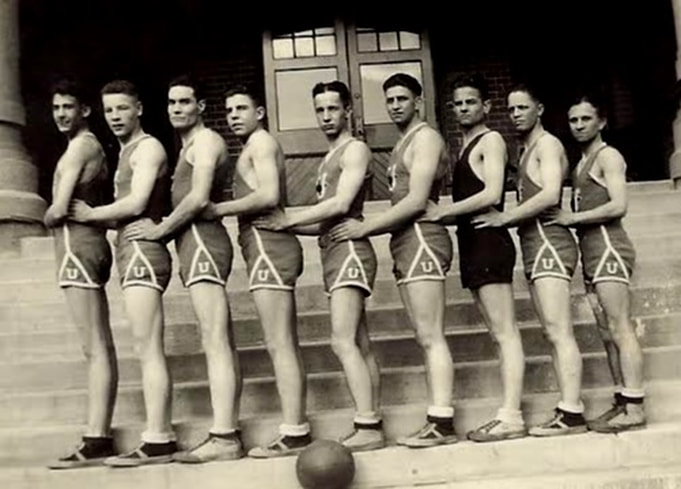

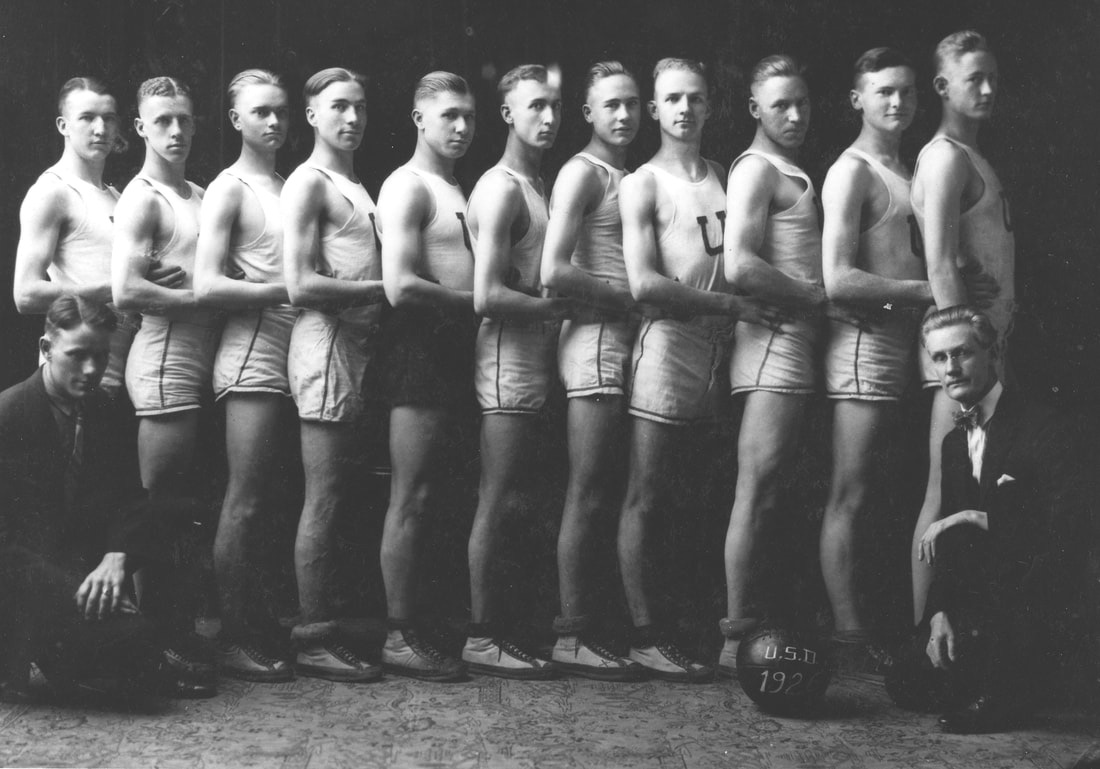

The Utah School for the Deaf Basketball Team, 1926. Kneeling L:-R: Coach A. LeRoy Stour and Manager Max W. Woodbury. Standing L-R: _ Despain, Wheelock Freston, Ferdinand Billiter, Arnold Moon, Andrew Loga, Charles Fowbae, Kenneth Burdett, Heber Christensen, Donald Robinson, George Laramie, Ross Thurston (Won 16 games. Lost two)

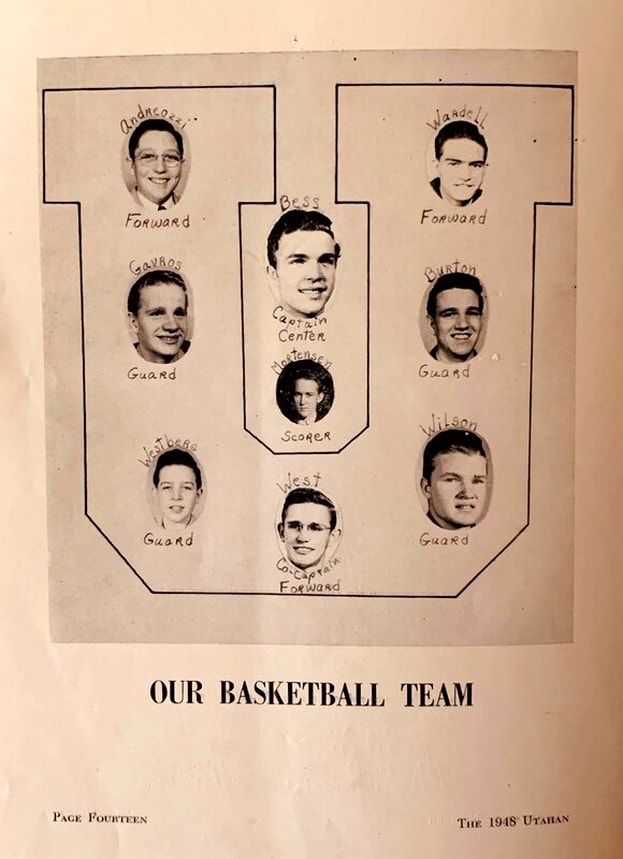

The Utah School for the Deaf Basketball Team, 1937-38. Front Row, L-R: Paul Baldridge, Forward; Paul Wood, Guard; Jesse Hales, Guard; Bill Watson, Caption, Forward; Phil Thornton, Center; David Wallace, Guard; Victor Lyon, Forward; Paul Gines, Forward,. Back Row, L-R: Kenneth C. Burdett, Coach; Eugene Plumby, Forward; Wayne Christiansen, Guard; Done Jacobs, Guard; Monroe Pedersen, Center; Joseph B. Burdett, Manager

The Utah School for the Deaf Basketball Team, 1944. In the front row: Kenneth Burdett, coach, kneeling at the left side, front row; Superintendent Boyd Nelson standing behind Kenneth Burdett Player 2 Marlo Honey Player 7 Mike Patterakis Player 7 Kirk Allred Player 2 Merrill Bauer Player 4 Pete Koukasatkis In the back row, Superintendent Boyd Nelson, standing at left side; Max Woodbury, standing at right side Player 3 Bruce Eyre Player 8 Lloyd Perkins Player 9 Tony Jelaco Player 4 Paul Loveland Player 5 Melwin Sorenson Player 6 Sam Judd

The Utah School for the Deaf Volleyball Team, 1955. First row, L-R: Elaine Sprouse, Dixie Lee Larson, Laura Williams, Afton Curtis Burdett, Instructor; Romona Vasquez, Lawana Simmons. Second Row, L-R: Carola Sell, Lois Williams, Virginia Brown, Darlene Green, Beverly Squire, Dorothy Mahoney. Third Row, L-R: Sue Wessman, Betty Jo Alldredge, Judy Jenkins, Gayle Marlow, Ilene Coles, Lucile Simmons

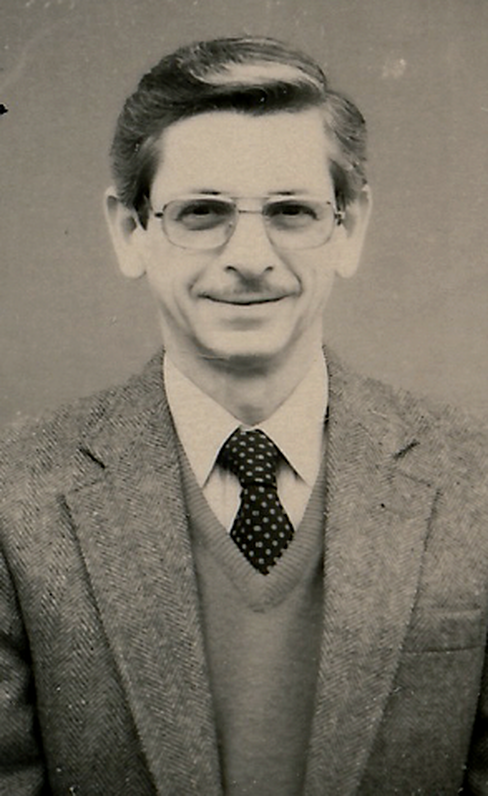

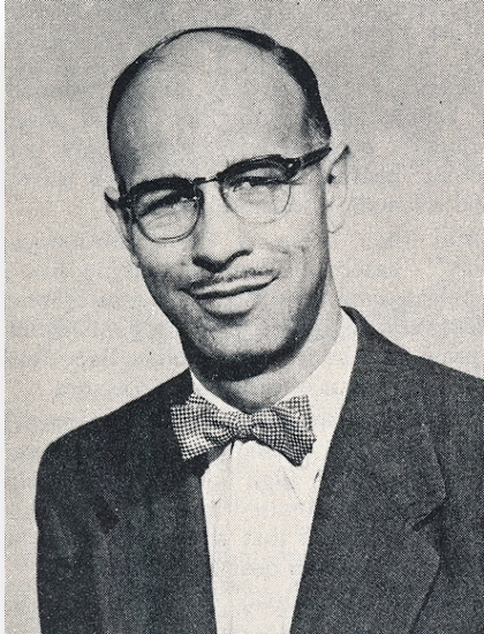

The Utah Association of the Deaf (UAD) had expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of coaches at the Utah School for the Deaf. In April 1959, the school hired Jerry Taylor as its physical education and athletic coaching director. Jerry recently graduated from Gallaudet College, where he majored in physical education. UAD hoped that Jerry's appointment would lead to room for progress, as success in sports requires good equipment and strong coaching. Despite Idaho and Colorado having excellent athletic students and great coaches, Jerry's drive and enthusiasm for progress never wavered. He impressed the UAD and became the school's athletic director, successfully leading USD's athletic programs.

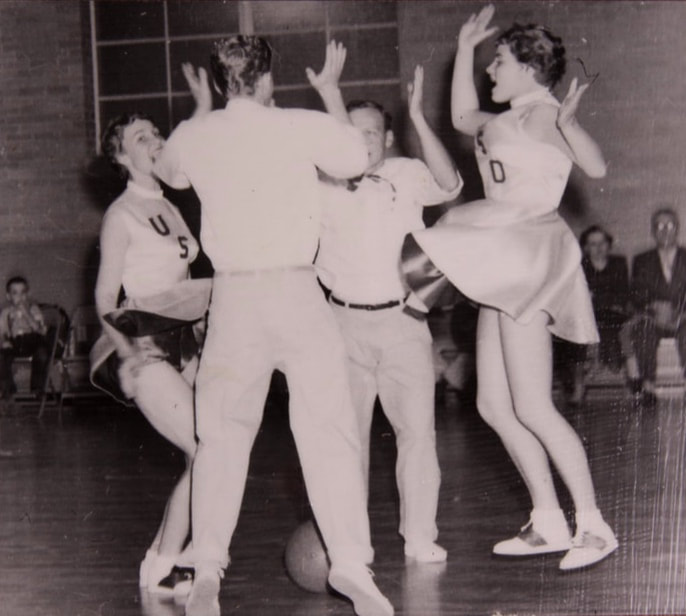

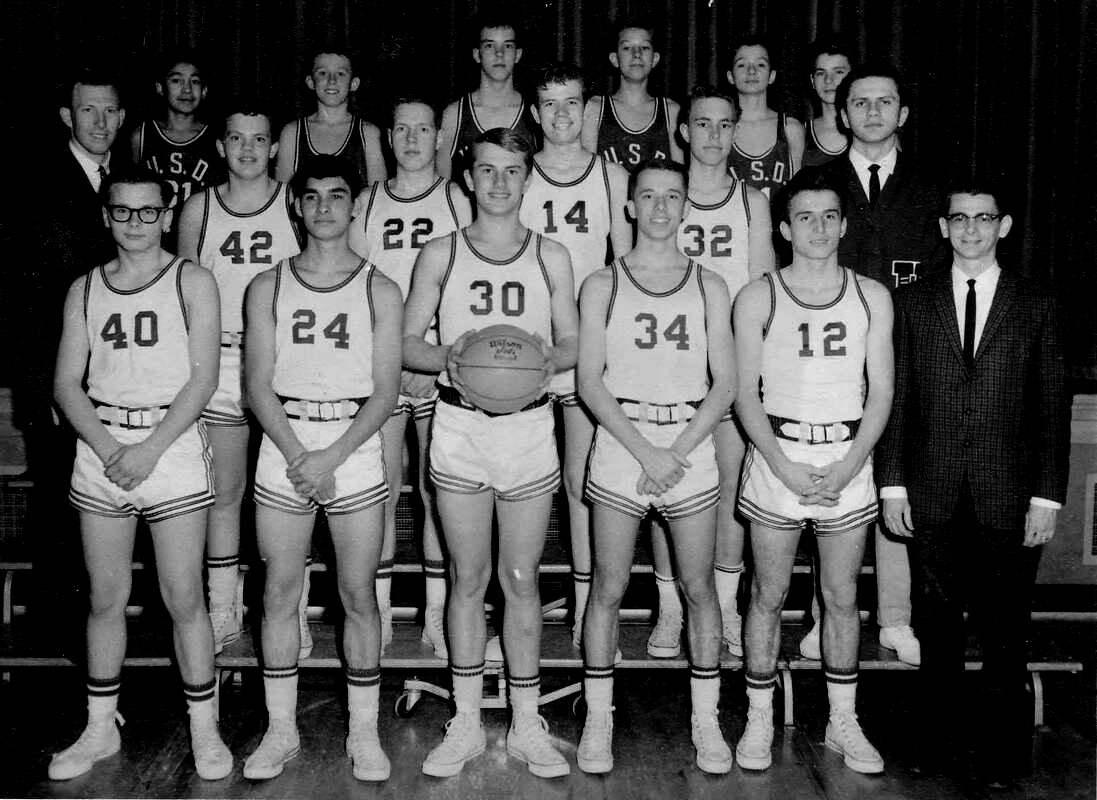

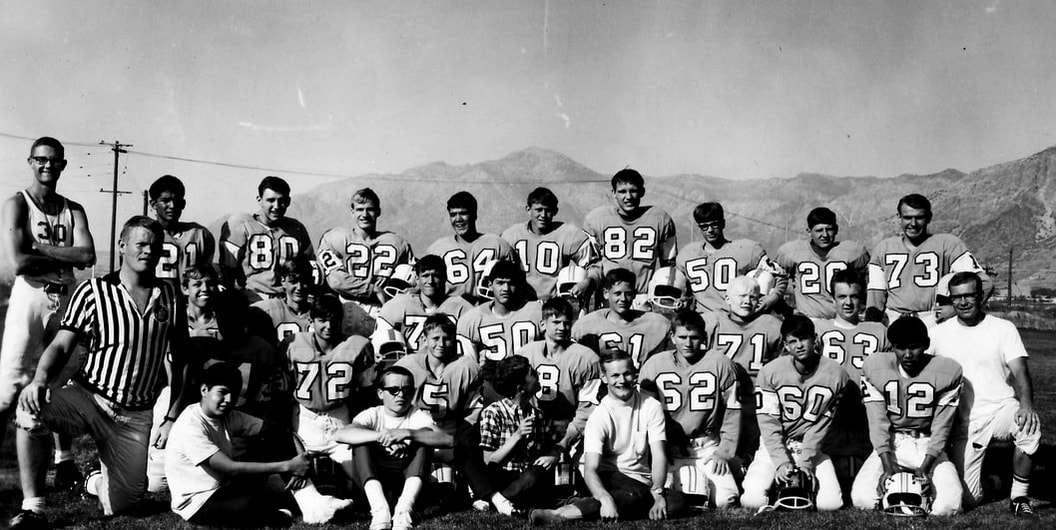

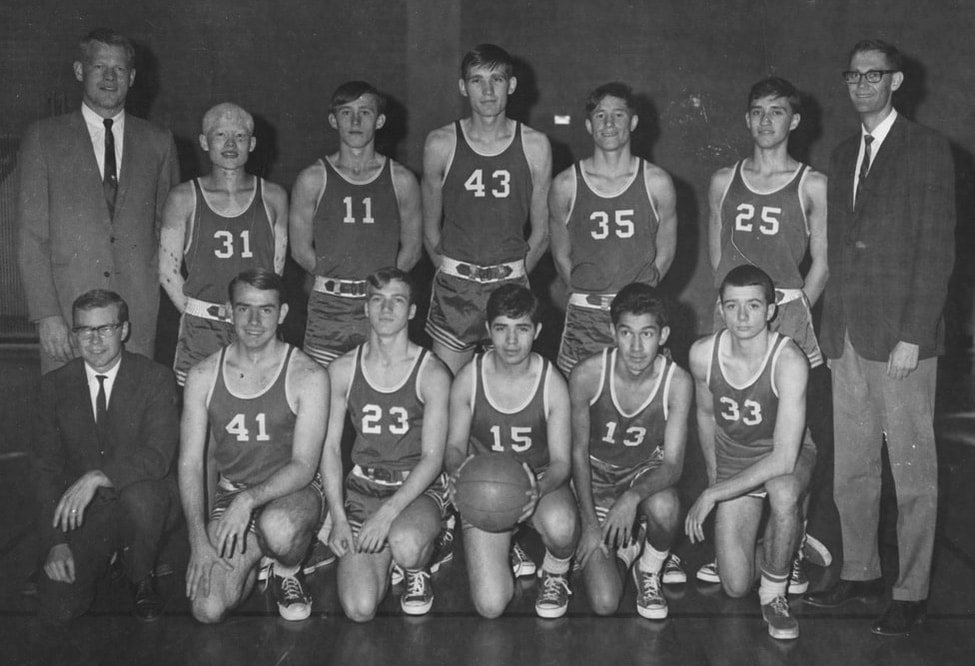

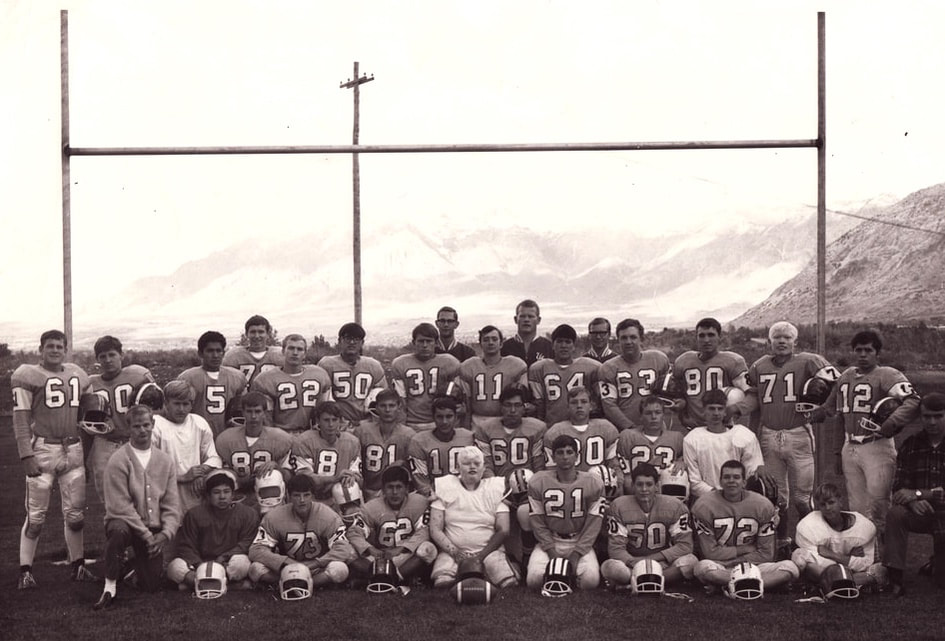

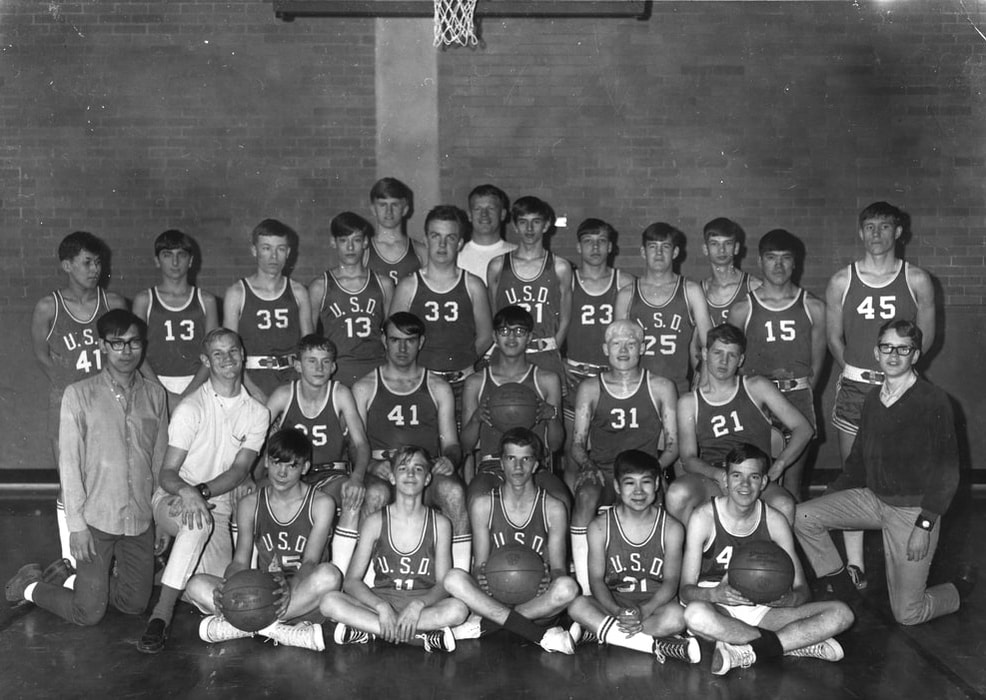

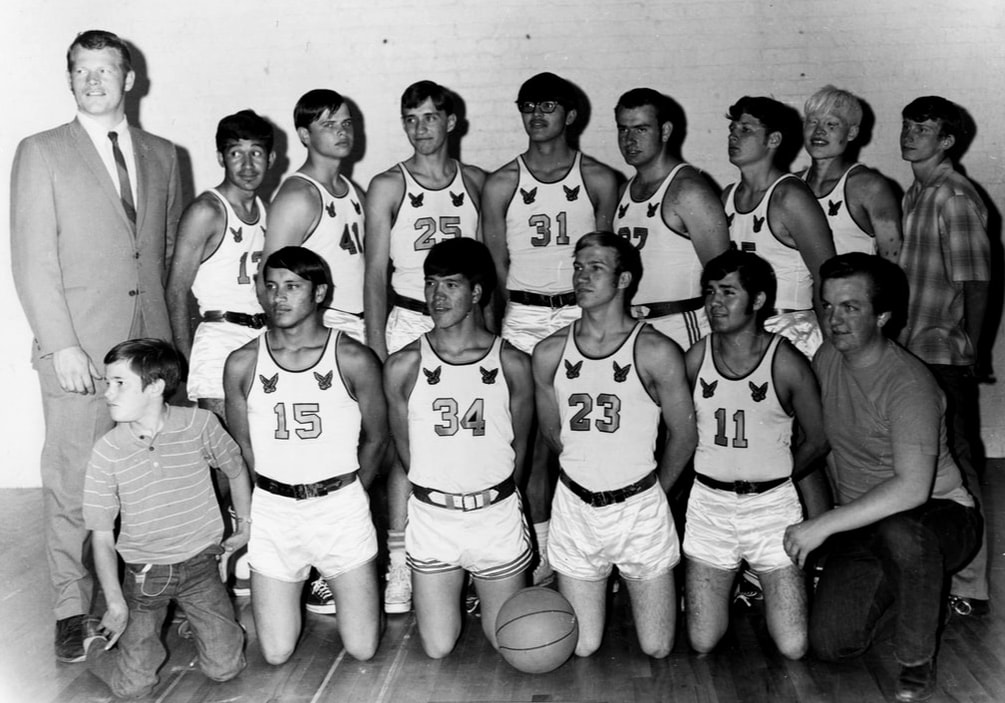

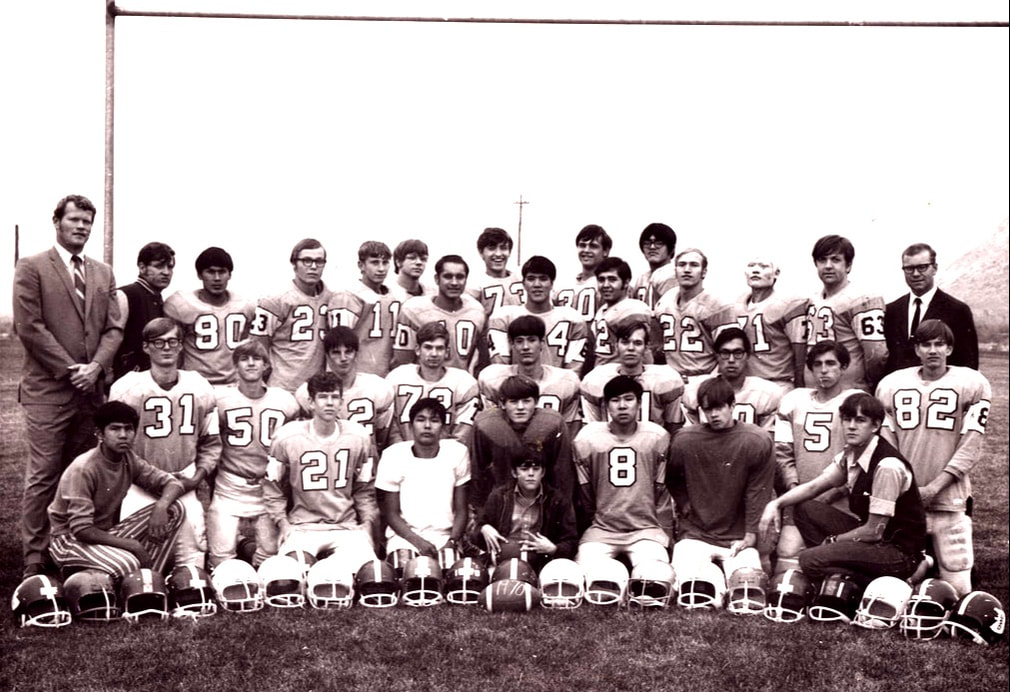

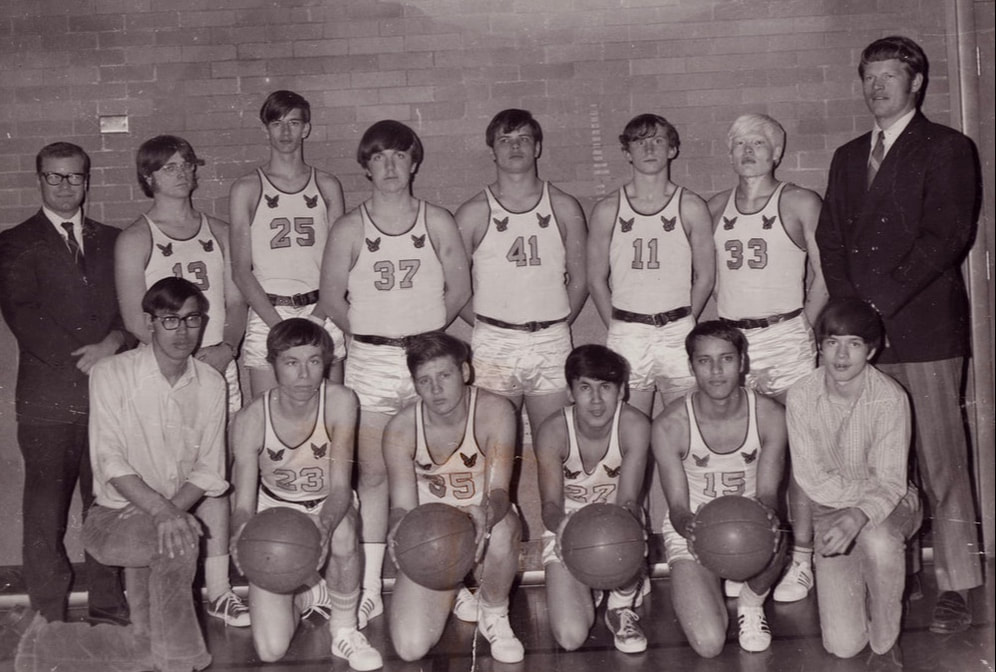

Over the years, USD has offered various sports, including cross country, volleyball, basketball, baseball, football, soccer, cheerleading, track, and pep club, as shown in the photos below. The games were started by the vibration of a drum.

Over the years, USD has offered various sports, including cross country, volleyball, basketball, baseball, football, soccer, cheerleading, track, and pep club, as shown in the photos below. The games were started by the vibration of a drum.

Did You Know?

In the late 1800s, the Utah School for the Deaf became affiliated with the University of Utah (U of U). During this time, several football games were played between deaf school boys and university students. Since they shared a campus, athletic events became the main way USD and U of U students interact. After the Utah School for the Deaf moved to Ogden, Utah, the boys continued to play football games among themselves. On at least one occasion, they invited the team from the Agricultural College in Logan, Utah, to play in Ogden. (Roberts, 1994).

The Impact of the "Y" System on Athletic Programs

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

In the fall of 1962, the Utah Deaf community was surprised by the revolutionary changes at the Utah School for the Deaf, which introduced the dual-track program, also commonly known as the "Y" system. The unexpected change had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children, evoking a sense of empathy within the community. The Utah Association of the Deaf, which advocated for sign language, was unaware that the Utah Council for the Deaf had spearheaded the change, advocating for speech-based instruction and successfully pushing for its implementation at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962). It is believed that Dr. Bitter was a member of this council. The dual-track program provided an oral program in one department and a simultaneous communication program in another department, which was later replaced by a combined system. However, the dual-track policy mandated that all Deaf children begin with the oral program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Gannon, 1981). The Utah State Board of Education, a key player in educational policy, approved this policy reform on June 14, 1962, with endorsement from the Special Study Committee on Deaf Education (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). The newly hired superintendent, Robert W. Tegeder, accepted the parents' proposals and initiated changes to the school system (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter, 1962; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). This new program not only affected the lives of Deaf children but also their families.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

At the time, Jerry Taylor was the coach of the signing team, while Bert Chaston, a staff member of the oral department, was the head coach of the oral team (Ruth Taylor, personal communication, February 11, 2015). For more information on the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf, please visit the "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream" webpage.

The 1962 and 1969 protests were sparked by dissatisfaction with the dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, the separation of oral and sign language situations, and the school administration's dismissal of their outcry.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

At the time, Jerry Taylor was the coach of the signing team, while Bert Chaston, a staff member of the oral department, was the head coach of the oral team (Ruth Taylor, personal communication, February 11, 2015). For more information on the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf, please visit the "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream" webpage.

The 1962 and 1969 protests were sparked by dissatisfaction with the dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, the separation of oral and sign language situations, and the school administration's dismissal of their outcry.

Following the 1962 protest against social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a steadfast advocate for oral and mainstream education, and his oral supporters suspected that the Utah Association of the Deaf had organized the student strike. The Utah State Board of Education conducted an investigation but found no evidence of any connection between the students and the Utah Association for the Deaf (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). In the face of societal segregation, the simultaneous communication students demonstrated their unwavering determination and courage by staging their own protests.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

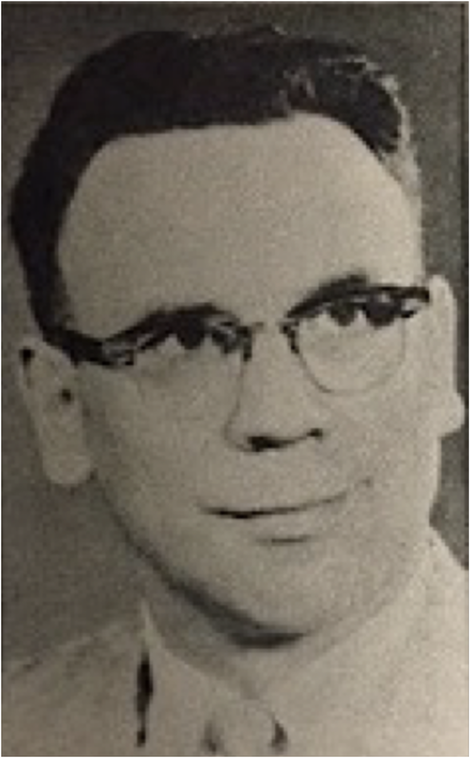

Kenneth L. Kinner, a 1954 Utah School for the Deaf graduate and father of two Deaf children, Deanne (Class of 1979) and Duane (Class of 1991 from the Idaho School for the Deaf), shared an incident from the 1970s. The mother of an oral girl insisted on her daughter's transfer to Ben Lomond High School, part of the USD extension program, situated between 7th and 9th Streets and Harrison Blvd. Other parents also requested the same option for their children, as they wanted them to attend everyday social activities and sports with hearing peers. They urged their best-prepared children to integrate into mainstream society. As predicted by the Utah Association of the Deaf, this resulted in the crippling of the USD athletic programs. When Ben Lomond High School grew overcrowded, some students transferred to Ogden High School for two years, from 1973 to 1975. Some oral students participated in hearing sports teams, while others did not. Only Bruce Aldridge, an oral student, had his parents' consent to participate in USD sports (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2010).

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

Kenneth L. Kinner, a 1954 Utah School for the Deaf graduate and father of two Deaf children, Deanne (Class of 1979) and Duane (Class of 1991 from the Idaho School for the Deaf), shared an incident from the 1970s. The mother of an oral girl insisted on her daughter's transfer to Ben Lomond High School, part of the USD extension program, situated between 7th and 9th Streets and Harrison Blvd. Other parents also requested the same option for their children, as they wanted them to attend everyday social activities and sports with hearing peers. They urged their best-prepared children to integrate into mainstream society. As predicted by the Utah Association of the Deaf, this resulted in the crippling of the USD athletic programs. When Ben Lomond High School grew overcrowded, some students transferred to Ogden High School for two years, from 1973 to 1975. Some oral students participated in hearing sports teams, while others did not. Only Bruce Aldridge, an oral student, had his parents' consent to participate in USD sports (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2010).

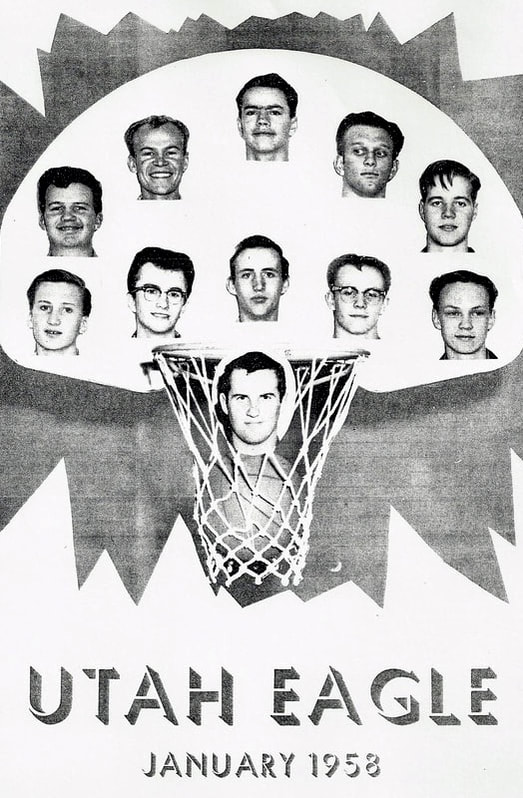

The Sports Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf

from 1959 to 1976

from 1959 to 1976

The Utah School for the Deaf Participates

in the Western State Basketball Classic Tournament

in the Western State Basketball Classic Tournament

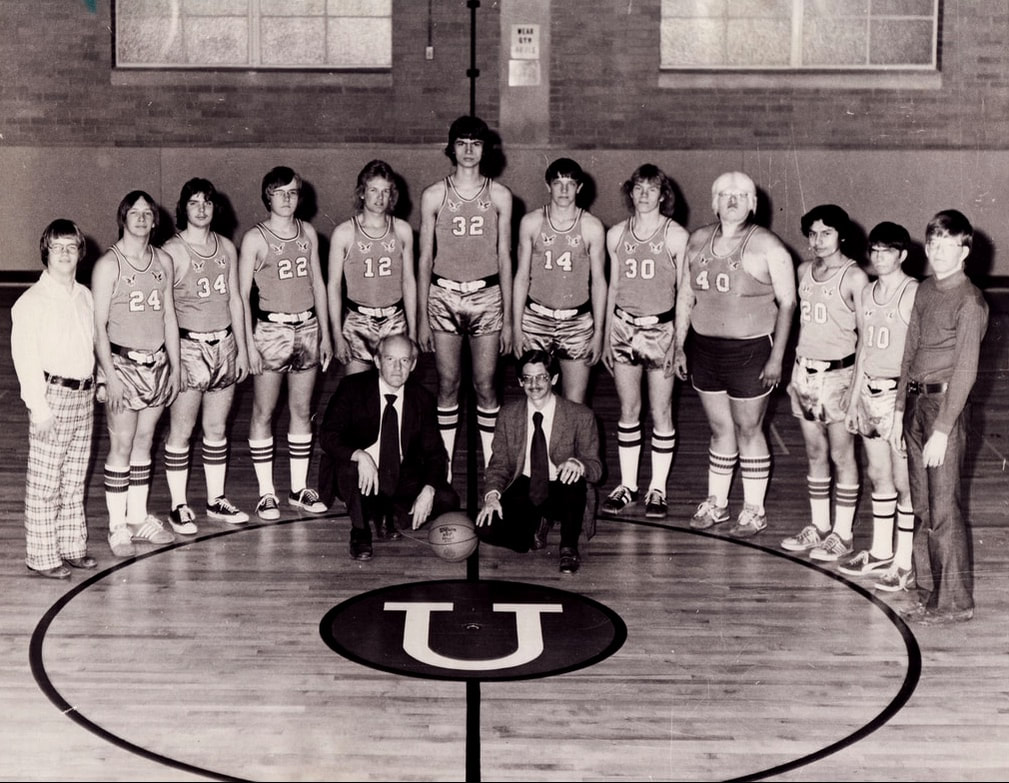

A small group of basketball players from USD's Total Communication Division were able to participate in the Western State Basketball Classic (WSBC) during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The WSBC was a basketball tournament specifically designed for teams with Deaf players, and it included teams from schools such as the California School for the Deaf-Riverside, California School for the Deaf-Fremont, Oregon School for the Deaf, Washington School for the Deaf, Arizona School for the Deaf and the Blind, and Phoenix Day School for the Deaf. In previous years, other schools had also participated, including the Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind, Marlton School, a Los Angeles-based program for Deaf students, the Colorado School for the Deaf and the Blind, and the New Mexico School for the Deaf. Each school took turns hosting the competition.

The tournament provided an opportunity for USD basketball teams to interact with their peers from several state schools for the deaf before, during, and after games. In addition to basketball games between the eight boys' and eight girls' teams and cheerleading competitions between the participating schools, WSBC also offered social events for the participants. The superintendents of the eight participating schools and the athletic directors of the institutions convened for a meeting. Furthermore, fans from the Deaf community flocked to watch the games. Every year, Deaf school students eagerly anticipate competing against their peers while communicating in American Sign Language, their natural language.

The tournament provided an opportunity for USD basketball teams to interact with their peers from several state schools for the deaf before, during, and after games. In addition to basketball games between the eight boys' and eight girls' teams and cheerleading competitions between the participating schools, WSBC also offered social events for the participants. The superintendents of the eight participating schools and the athletic directors of the institutions convened for a meeting. Furthermore, fans from the Deaf community flocked to watch the games. Every year, Deaf school students eagerly anticipate competing against their peers while communicating in American Sign Language, their natural language.

The Impact of Mainstreaming on

Athletic Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf

Athletic Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf

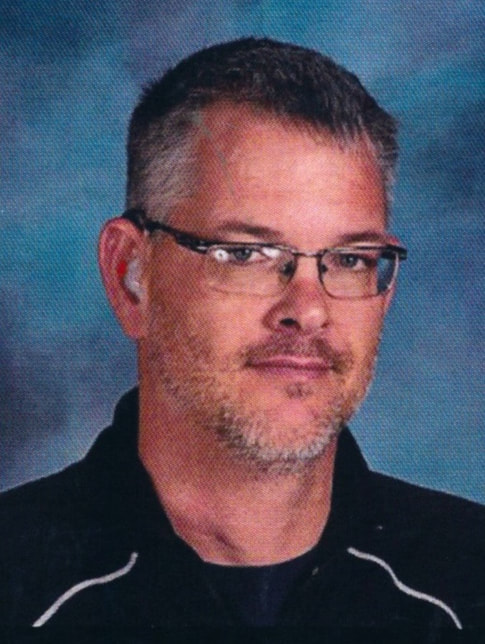

During the 1980s, the number of students at USD decreased due to mainstreaming. After Jerry Taylor retired as athletic director in 1987, Mike Hillstrom took over as coach and eventually phased out all sports except basketball and volleyball. In 1986 and 1987, the sports program only had a junior varsity basketball team, with Tintic High School serving as the varsity team. The team competed against other small schools across the country, including teams from Tintic High School, Rowland Hall High School, Dugway High School, and Rich County High School. Despite being among the few basketball teams with perfect records, USD lost all ten games. The following year, in 1987–88, USD's low numbers and struggling situation led to its expulsion from the Utah High School Athletic Association. The team relocated to the Christian Athletic Association (CAA), hosting games at the USDB campus in Ogden. The CAA also organized a volleyball league, in which USD participated. According to Mike Hillstrom, the athletic programs closed due to the ongoing decline in numbers (Mike Hillstrom, personal communication, May 30, 2014). You can find more information about "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective" on this webpage.

The athletic program's closure in 1989 devastated the Utah Deaf community. The popularity of mainstreaming since the 1960s led to widespread integration in Utah, and the implementation of the Dual-Track Program and mainstreaming in the early 1960s also led to the closure of the Ogden residential campus in the early 1990s. In 1993, the Utah School for the Deaf and the Utah School for the Blind consolidated on a new campus at 742 Harrison Boulevard in Ogden, Utah (Leers, November 1, 1988, p. B1; Deseret News, November 4, 1988; Bannister, UAD Bulletin, February 1989). Regrettably, all of the school's sports trophies disappeared during the move. The exact location of the trophies remains unknown (Jerry Taylor, Personal Communication, February 2012).

Following the closure of USD's athletic programs, the local Deaf community, particularly former USD mainstreamed students, displayed remarkable perseverance. They continued participating in Deaf sports outside of school, a testament to their unwavering spirit. Many Deaf individuals in Utah joined local sports organizations like the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf and the Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf. Members of the Utah Deaf community also competed on regional and national sports teams. They actively participated in four organizations: the Far West Athletic Association of the Deaf, the Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf, the American Athletic Association of the Deaf, and the USA Deaf Sports Federation.

Following the closure of USD's athletic programs, the local Deaf community, particularly former USD mainstreamed students, displayed remarkable perseverance. They continued participating in Deaf sports outside of school, a testament to their unwavering spirit. Many Deaf individuals in Utah joined local sports organizations like the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf and the Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf. Members of the Utah Deaf community also competed on regional and national sports teams. They actively participated in four organizations: the Far West Athletic Association of the Deaf, the Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf, the American Athletic Association of the Deaf, and the USA Deaf Sports Federation.

Did You Know?

In about 1895, the Utah School for the Deaf added a physical education program in Salt Lake City, Utah. After moving to Ogden, Utah, in 1896, the school built a gymnasium and hired a physical education instructor (Roberts, 1994).

The Rebirth of the Athletic Programs

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

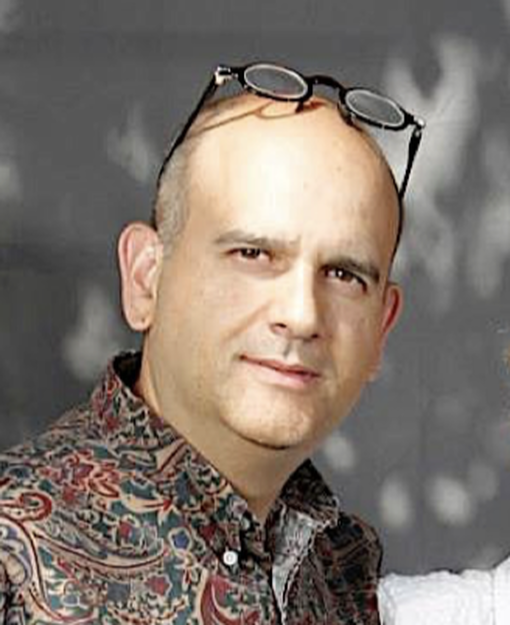

Julio Diaz, a sports enthusiast, 1983 graduate of the Florida School for the Deaf, husband of JMS co-founder Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, and father of three Deaf children, requested a restatement of the athletics program shortly after the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf (JMS) merged with the Utah School for the Deaf in 2005. Linda Rutledge, superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, approved this request.

In 2006, Julio Diaz's hard work finally paid off when the Utah High School Activities Association board of trustees decided to revive activities and athletics for Deaf and blind students, irrespective of where they attended school, marking a significant development. The new rule permitted the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind (USDB) teams to utilize students from any high school, provided the board designated them as students using their services. However, building athletic programs from scratch proved daunting, and it took a long time for the USDB to establish them. Mike Hillstrom, a long-time teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf and activities director, says that when USD had 200 students living in a residential setting, they used to field relatively large teams. However, in the late 1980s, an increasing number of students began attending public schools, and the USD started providing its services and teachers in those high schools rather than requiring students to live away from their families on an Ogden residential campus. As a result, the school's residential part was getting smaller and smaller, which led to activities and athletic programs dying as students transferred away from campuses (Donaldson, Deseret News, March 6, 2007).

Julio was hopeful that opportunities for sports would increase in the future despite the mainstreaming situation. However, during the 2008-2009 school year, the USDB faced a budget cut of $2.25 million under the administration of Interim Superintendent Timothy W. Smith. At that time, Superintendent Smith did not recognize the value of athletic programs and moved to discontinue them. Members of the Utah Deaf community urged him not to close the programs. Eventually, Superintendent Smith agreed to reinstate the athletic program, and Deaf volunteers stepped in to help with volleyball, basketball, and track and field.

Julio was hopeful that opportunities for sports would increase in the future despite the mainstreaming situation. However, during the 2008-2009 school year, the USDB faced a budget cut of $2.25 million under the administration of Interim Superintendent Timothy W. Smith. At that time, Superintendent Smith did not recognize the value of athletic programs and moved to discontinue them. Members of the Utah Deaf community urged him not to close the programs. Eventually, Superintendent Smith agreed to reinstate the athletic program, and Deaf volunteers stepped in to help with volleyball, basketball, and track and field.

After two years of planning, in 2008, the USD boys' and girls' basketball teams finally competed in a national tournament in Oregon. According to Jen Byrnes, a graduate of the Idaho School for the Deaf and the Deafhead coach of the girls' basketball team, the event was an eye-opener for USD athletes. "The girls were in a national environment," she explained. They're so isolated that it was the first time for several of them to see conversations among the Deaf population. "Hey, they're teens just like us," they said. They're talking about boys and schools. "As a result, they gain access to a larger community. "Some students have identity issues," said Craig Radford, the Deaf USD head boys' coach. "Being part of the larger community helps them build more confidence as Deaf individuals." Jen and Craig agreed that the teams' skills improved, and that the students are now receiving excellent community support as individuals associated with the school become accustomed to the idea that sports are returning to USD (Sights & Sounds, May 2008).

The Utah Deaf community had a dream that finally came true. Despite facing budget constraints and a shortage of students, the Utah School for the Deaf and Jean Massiue School of the Deaf students could participate in sporting programs. With the help of more coaches, even more mainstream students could practice and play games at the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. It was fortunate that they had access to the gym!

Did You Know?

Sports have always played a significant role in the Deaf community. Deaf children attending state deaf schools across the United States, such as the Utah School for the Deaf, enjoyed participating in sports with their peers. The older Utah School for the Deaf graduates who participated in sports on the Ogden residential campus wanted the mainstream students to have the same opportunities. While the Utah Community Center for the Deaf (later renamed the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing) was being built in Taylorsville, Utah, the Utah Deaf community suggested including a gym. The committee tasked Norman Williams, a 1962 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, with finding the ideal gym for the facility. Norman visited several gyms in the area, but none of them met his expectations. He later visited the Idaho School for the Deaf, where he saw a new full-size basketball court with bleachers and was impressed with its size. He recommended that the center follow suit, and consequently, they built the gym to accommodate a basketball court with movable bleachers (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2008; Norman Williams, personal communication, May 8, 2012). Their goal was to provide sports opportunities to individuals who would not have equal access to public school athletic programs.

The Rebirth of the Western States Basketball Classic

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Since the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Western States Basketball Classic (WSBC) has been an annual tournament featuring teams from eight schools for the deaf. After a long absence due to a lack of students to form a team, the Utah School for the Deaf returned to the tournament in 2007 and has since competed in four classics. However, maintaining a spot at the WSBC is challenging, as only eight schools receive invitations annually. If one school leaves, another takes its place. The teams that played at the Sanderson Community Center gym were open to students from the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf. The WSBC invited Utah School for the Deaf in 2009, allowing students to connect and learn while competing against other state schools for the deaf. In the March 2009 issue of the UAD Bulletin, Mike Hillstrom reported that twenty-five students attended WSBC, describing the event as so worthwhile and life-changing (Hillstrom, UAD Bulletin, March 2009).

During the Great Recession of 2008–2012, Julio Diaz reported that the Utah School for the Deaf and the Blind faced significant financial challenges in 2012. Dr. Jennifer Howell, who was the then-Associate Superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf, informed Jill Radford, then-principal of Jean Massieu School, that the Utah School for the Deaf would have to withdraw from the 2011 WSBC tournament. Jill Radford, a graduate of the Idaho School for the Deaf, offered to volunteer to take over the 2011 WSBC rather than have USDB cancel it, despite her other responsibilities, which included being the only full-time administrator in charge of 97 students from preschool through high school. Jill believed in the event and thought it would be a valuable experience for Deaf students. She also considered WSBC a terrific way for Deaf students to compete in sports, socialize, and establish life-long friendships that would help them thrive in life, just like the rest of the Utah Deaf community. She also stated that the students and superintendents who met during the event benefited from WSBC. It provided opportunities for Deaf students from small towns to interact with Deaf students from other areas, allowing them to recognize that there was a bigger world out there for them (Julio Diaz, personal communication, October 2010).

During the Great Recession of 2008–2012, Julio Diaz reported that the Utah School for the Deaf and the Blind faced significant financial challenges in 2012. Dr. Jennifer Howell, who was the then-Associate Superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf, informed Jill Radford, then-principal of Jean Massieu School, that the Utah School for the Deaf would have to withdraw from the 2011 WSBC tournament. Jill Radford, a graduate of the Idaho School for the Deaf, offered to volunteer to take over the 2011 WSBC rather than have USDB cancel it, despite her other responsibilities, which included being the only full-time administrator in charge of 97 students from preschool through high school. Jill believed in the event and thought it would be a valuable experience for Deaf students. She also considered WSBC a terrific way for Deaf students to compete in sports, socialize, and establish life-long friendships that would help them thrive in life, just like the rest of the Utah Deaf community. She also stated that the students and superintendents who met during the event benefited from WSBC. It provided opportunities for Deaf students from small towns to interact with Deaf students from other areas, allowing them to recognize that there was a bigger world out there for them (Julio Diaz, personal communication, October 2010).

Despite the financial challenges that USDB faced, Julio Diaz noted that Jill Radford and two chairpersons, Brian Thornsberry, USD Athletic Director and 1991 graduate of the Idaho School for the Deaf, and Craig Radford, an alumnus of the Idaho School for the Deaf and a long-time volunteer high school basketball head coach, were able to host the 35th Annual Western States Basketball Classic in 2009. They worked extremely hard to ensure that the event went off without a hitch for everyone involved. Julio said that it worked absolutely perfectly (Julio Diaz, personal communication, October 2010).

Julio Diaz believed that the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) should have the same opportunity as public high schools to participate in the Utah High School Athletic Association (UHSAA) and compete against other high school teams. However, to compete in the Western States Basketball Classic (WSBC), USD had to become a UHSAA member. Diaz warned Dr. Jennifer Howell that leaving the UHSAA would make it difficult to re-enter and fit USD's players into the existing teams' schedules. Even if a new superintendent revived athletics and restored funding, the UHSAA's lengthy and selective application process would still limit participation (Julio Diaz, personal communication, October 2010). After much persuasion, Dr. Howell agreed to keep the athletic programs running. However, Steven W. Noyce, a former student of Dr. Bitter's oral training program and a vocal advocate for mainstreaming, became the superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind in 2009. He was not fond of sporting activities and believed that Deaf and hard of hearing students should participate in public school sports programs. The Utah Deaf community speculated that Superintendent Noyce pressured Dr. Howell to cancel sporting events. Fortunately, the Utah Deaf community triumphed and won, saving the USD sporting programs.

In 2015, the Utah School for the Deaf hosted the Western State Basketball and Cheerleading Classics from January 28th to January 31st at the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center and Taylorsville High School. The event was a success thanks to months of planning and preparation. Under the guidance of Deaf coach Wade Hester, the Utah School for the Deaf boys' team won the WSBC championship. In the final game, the USD boys' team defeated Phoenix School for the Deaf with a score of 59 to 40 (Tanner, UAD Bulletin, February 2015; Montalette, UAD Bulletin, February 2015). Craig Radford, the then-Director of Business Development at ZVRS, flew from Florida to Utah to support the team. Having coached these boys for ten years, he knew them from a young age, and they regarded him as a mentor, teacher, and friend. Craig must have been ecstatic to see such a strong array of players win the championship match.

Following the end of Steven W. Noyce's tenure in 2013, Joel Coleman, a former Utah State Board of Education member, assumed the role of superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. He also appointed Michelle Tanner as an associate superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf. Their leadership was instrumental in the continued expansion and success of the school's athletic program.

Since 2006, the Utah School for the Deaf has run a sports program, participating in UHSAA-sponsored activities in the 1A region and the Western States Basketball and Cheerleading Classic each year. The program includes three deaf schools: Jean Massieu School of the Deaf (Salt Lake City), Kenneth Burdett School of the Deaf (Ogden), and Elizabeth DeLong School of the Deaf (Springville), which compete against other teams within and outside the state. These athletic programs are integral to motivating student-athletes and are a significant part of their deaf experience. Moreover, all-deaf sports provide an opportunity for Deaf students to compete against their peers from state schools for the deaf across the western United States and connect with other Deaf and hard of hearing students as well.

Since 2006, the Utah School for the Deaf has run a sports program, participating in UHSAA-sponsored activities in the 1A region and the Western States Basketball and Cheerleading Classic each year. The program includes three deaf schools: Jean Massieu School of the Deaf (Salt Lake City), Kenneth Burdett School of the Deaf (Ogden), and Elizabeth DeLong School of the Deaf (Springville), which compete against other teams within and outside the state. These athletic programs are integral to motivating student-athletes and are a significant part of their deaf experience. Moreover, all-deaf sports provide an opportunity for Deaf students to compete against their peers from state schools for the deaf across the western United States and connect with other Deaf and hard of hearing students as well.

In conclusion, the athletics program has achieved its current status thanks to Julio's hard work and the contributions of other volunteers like Jill, Craig, and others. Although athletics may not be part of the official curriculum, it is important to note that students deserve the same opportunities as their non-hearing peers. Participating in sports teaches students valuable lessons in discipline, sportsmanship, and physical control, among other things. More importantly, the social aspect of athletics allows students to develop leadership skills, work as a team, embrace the discipline required for regular practice and training, and recognize the need for good sportsmanship in their efforts. These skills are equally, if not more, important than physical ones.

Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf

Note

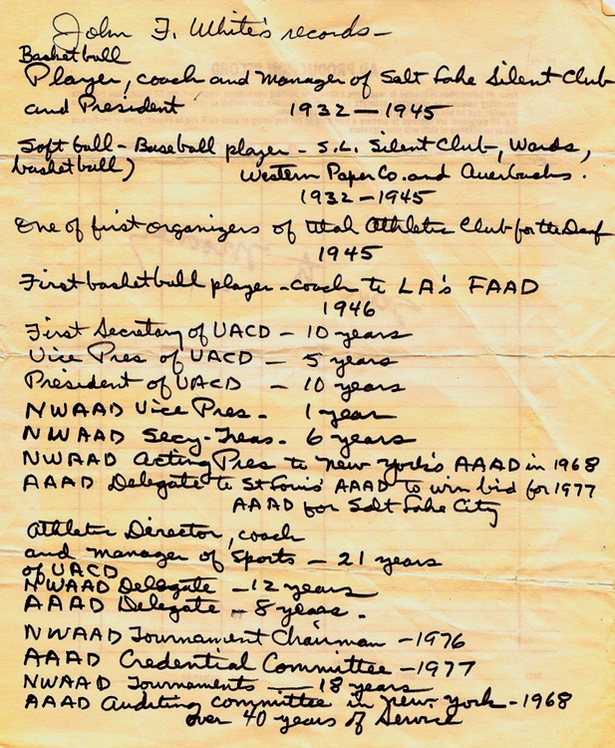

Deaf athletes from Utah participated in the first competition of the Far West Athletic Association of the Deaf as The Silent Club, leading to the founding of the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf in 1945. John (Jack) F. White, a sports enthusiast, collected most of the historical material published in the "Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf: 50th Anniversary Celebration 1947–1997" Program Book.

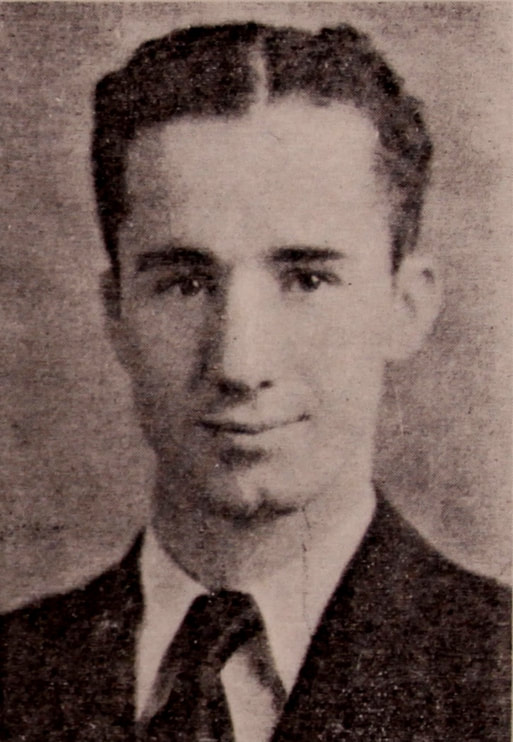

The Salt Lake Silent Club is Formed

John "Jack" F. White, a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1932, founded the Salt Lake Silent Club and sponsored a basketball team. His team would compete against other teams from Fort Douglas, a military training base near the University of Utah, the Salt Lake City Fire and Police Departments, and the Utah School for the Deaf. In 1945, they were given the opportunity to compete in out-of-state and regional competitions alongside other Deaf athletes. Jack then formed the Far West Athletic Association of the Deaf (FAAD) to unite and compete with other Deaf athletic clubs. Art Kruger, a well-known Gallaudet College graduate, founded the FAAD, which covers Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Idaho, Utah, and the rest of the western United States. In March 1946, Art asked Jack White if the Salt Lake Silent Club would participate in the FAAD basketball competition in Los Angeles, promising $350 if they agreed to compete against other Deaf club teams. Seeing this as a great opportunity, Jack convened a meeting of basketball players from Salt Lake City and Ogden (White, 1997).

The Establishment of the

Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf

Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf

Jack White convened a special meeting for a group of ballplayers from Ogden and Salt Lake City, informing them of Art Kruger's request. During the meeting, he encouraged them to start a new club and outlined how it would help the squad create a competitive relationship with FAAD. He proposed renaming the team "Salt Lake Athletic Club for the Deaf," but some players from Ogden felt that the name did not accurately represent them. After discussing potential team names, they finally agreed on "Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf," or UACD. George L. Laramie was chosen as the president and coach, while Jack was selected as the vice president and assistant coach. Larry Anderson was named the secretary and treasurer (White, 1997).

A newly formed club needed a gym to practice in before the upcoming tournament in Los Angeles, California. Jack approached a hearing acquaintance, John M. Knight, who happened to be the Salt Lake Police Commissioner, and requested permission for the UACD basketball team to practice and play games at the police precinct's basketball gym on State Street and First South. After the approval of the request, the team practiced and played games with various teams, such as the Salt Lake City Police Department, the Salt Lake Fire Department, and Fort Douglas (White, 1997).

As the tournament date approached, several UACD players dropped out, leaving the team with only six members. However, Jack, with his characteristic dedication, didn't panic. He recognized a few potential candidates in the 'woods' and sought out Edwin Ross Thurston. He also sought out Hooper, Alton Fisher from Utah, and Jack Downey from Boise, Idaho. His proactive approach to recruiting new players is a testament to his commitment to the team (White, 1997).

As the tournament date approached, several UACD players dropped out, leaving the team with only six members. However, Jack, with his characteristic dedication, didn't panic. He recognized a few potential candidates in the 'woods' and sought out Edwin Ross Thurston. He also sought out Hooper, Alton Fisher from Utah, and Jack Downey from Boise, Idaho. His proactive approach to recruiting new players is a testament to his commitment to the team (White, 1997).

The club coach, George Laramie, couldn't join the team in Los Angeles, California. Jack White took his place. However, the team faced a problem; they didn't have enough money to cover the cost of the trip and their stay in a hotel. Jack White wanted his team to take advantage of the opportunity to compete in an out-of-state tournament. So, he decided to take $200 from his savings to support the team and cover the costs of a $22 round-trip Greyhound bus ticket and hotel bookings. Larry Anderson's car carried three players, and Jack chose Ross Thurston as the team's delegate during the tournament. On their way to Los Angeles, the team stopped in Las Vegas, a small town with a general store and a motel. They boarded the bus to Los Angeles, excited to compete against other Deaf clubs (White, 1997).

Despite the setback of losing four of its top players to the Los Angeles Club for the Deaf, the UACD team showed resilience. They defeated the Utah team in the first game and went on to win the next two, earning the consolation title. The tournament secretary, Art Kruger, maintained his word and gave UACD $350 from the tournament cash. Jack received $200 of the sum, with the remaining $150 going to the UACD Treasury (White, 1997).

In 1947, Oakland, California, hosted the FAAD basketball tournament. The UACD team, under the guidance of coach Jack, showcased their prowess. They won the consolation bracket, triumphing over Hollywood 46-44 and San Francisco 32-15. Despite not clinching the championship, UACD's performance was commendable. They also secured the bid to host the 1948 tournament in Salt Lake City on February 27 and 28, a testament to their potential for future success (White, 1997).

Despite the setback of losing four of its top players to the Los Angeles Club for the Deaf, the UACD team showed resilience. They defeated the Utah team in the first game and went on to win the next two, earning the consolation title. The tournament secretary, Art Kruger, maintained his word and gave UACD $350 from the tournament cash. Jack received $200 of the sum, with the remaining $150 going to the UACD Treasury (White, 1997).

In 1947, Oakland, California, hosted the FAAD basketball tournament. The UACD team, under the guidance of coach Jack, showcased their prowess. They won the consolation bracket, triumphing over Hollywood 46-44 and San Francisco 32-15. Despite not clinching the championship, UACD's performance was commendable. They also secured the bid to host the 1948 tournament in Salt Lake City on February 27 and 28, a testament to their potential for future success (White, 1997).

Ross Thurston was appointed chairman of the 1948 FAAD competition in Salt Lake City, Utah. He then formed a committee, which included Larry Anderson (secretary and program), John "Jack" F. White (entertainment), Rodney Walker (treasurer), Eugene Plumby (trophies), George L. Laramie (reservations), Earl P. Smith (concessions), Joseph Burnett (entertainment for the Ogden Division), and Earl Rogerson (entertainment for the Ogden Division). Verl W. Thorup (chairman), Catherine J. Morgan, and Gladys Hind were also members of the UACD Board of Trustees. Deseret Gymnasium, located at 37 College Place, hosted the tournament. The committee paid $200 to book the gymnasium for two nights. In addition, they sold a lot of raffle tickets and held several parties and dinners to raise funds for the tournament. These events took place on the plaza where the large water fountain stands today, between State and Main Streets and South and North Temple Streets, behind the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, and near the current Church Office Building (White, 1997; Gary L. Leavitt, personal communication, 1995; Walker, 2006).

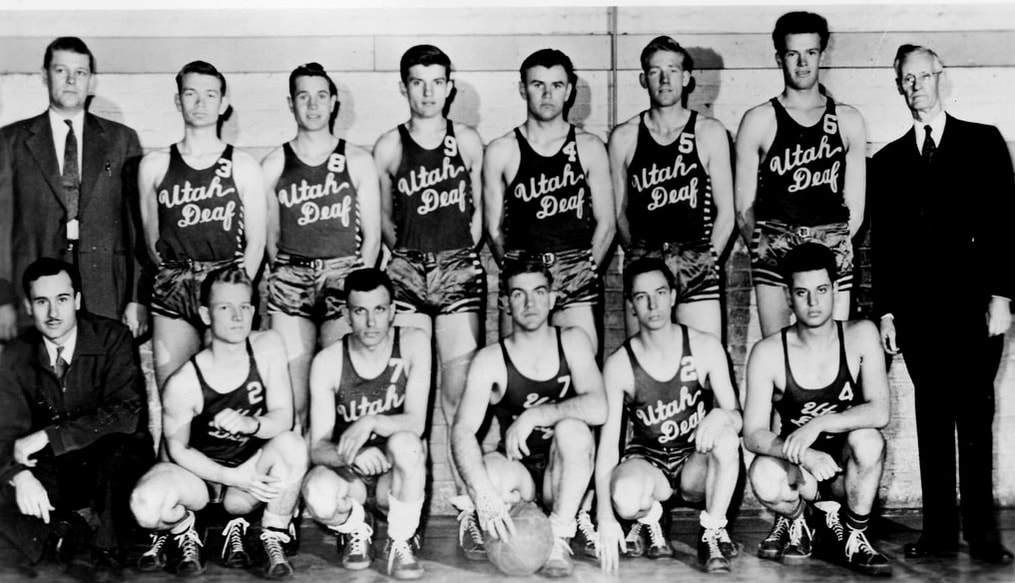

The Utah Athletics Club of the Deaf Team at the Far West Athletic Association of the Deaf Tournament in Salt Lake City, Utah, 1948. Standing L-R: Eugene Phumby (Coach), Lloyd Perkins, Larry Anderson, Clem Sefvy, Phil Thornton, Don Jacobs, Shirley Barney, Jack White (manager). Seated L-R: Ronald Bess, Paul Gines, Paul Wood, Kird Allred, Bruce Eyre

In 1957, the Utah Athletics Club of the Deaf (UACD) departed from the FAAD region and joined the newly established Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf (NWAAD). The players were responsible for arranging their own transportation, hotel accommodations, and meals. In 1957, the team traveled to various locations, including California, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Canada (White, 1997).

Rodney W. Walker was elected president of the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf in 1958 due to his curiosity and an offer to attend a meeting of the UACD; he maintained the position for ten years. He proposed that they launch a UACD newsletter for members, and he chose his first wife, Georgia Hendricks Walker, to serve as editor and publisher. The annual dues were one dollar. To a total of 175, the number of members climbed three or fourfold. Although new members were not required to participate in activities such as basketball, bowling, or softball, the newsletter was the reason for the membership growth (Walker, 2006).

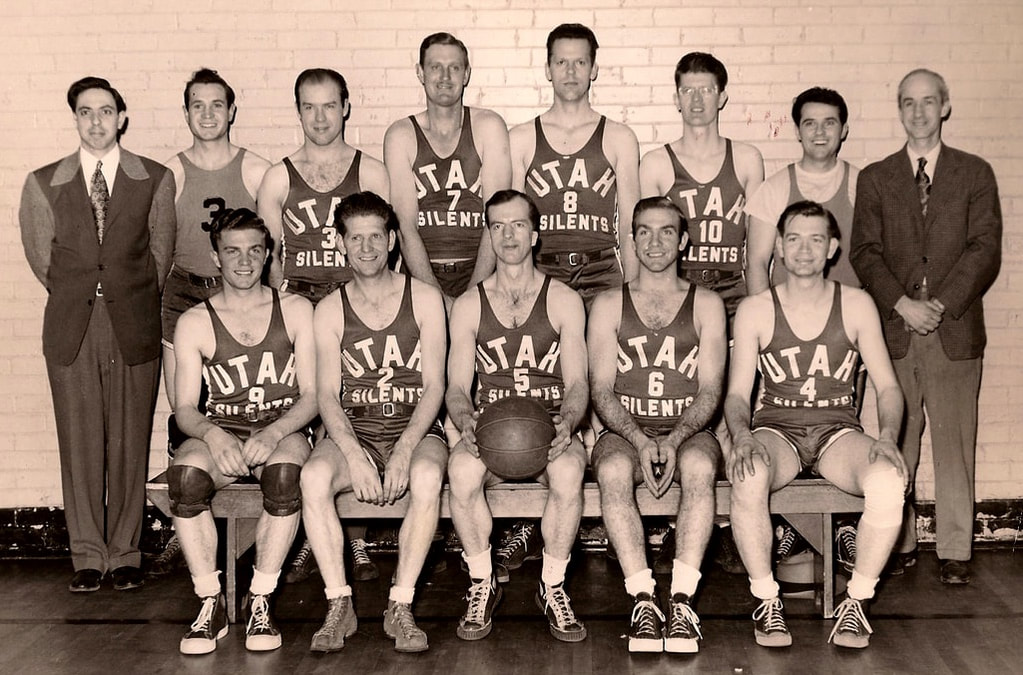

The Utah Athletics Club of the Deaf team at the Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf Tournament in Salt Lake City, Utah in 1962. Front row L-R: R: .J. Christensen, R. Bess, R. Potter, K. Stewart, R. Kerr; 2nd Row L-R: R. Johnston, R. Bonnell, V. Jones, A. Valdez; 3rd row, L-R: R. Loveland, K. Nelson, L. Curtis, B. Harvey, John F. White (manager/coach)

Rodney W. Walker became the President of the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf in 1958. His curiosity and willingness to attend a meeting of the UACD led to his election, and he held the position for a decade. Rodney suggested creating a UACD newsletter for members and chose his first wife, Georgia Hendricks Walker, to serve as editor and publisher. The annual fee for the newsletter was one dollar, contributing to a three- or four-fold increase in membership, reaching a total of 175. The newsletter drove the membership growth, even though new members were not required to participate in basketball, bowling, or softball activities (Walker, 2006).

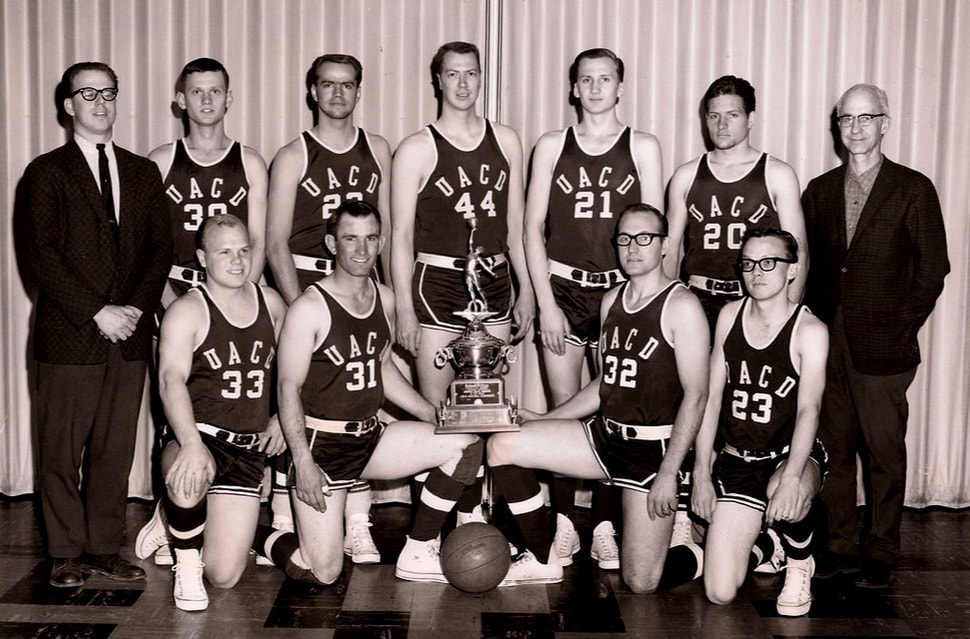

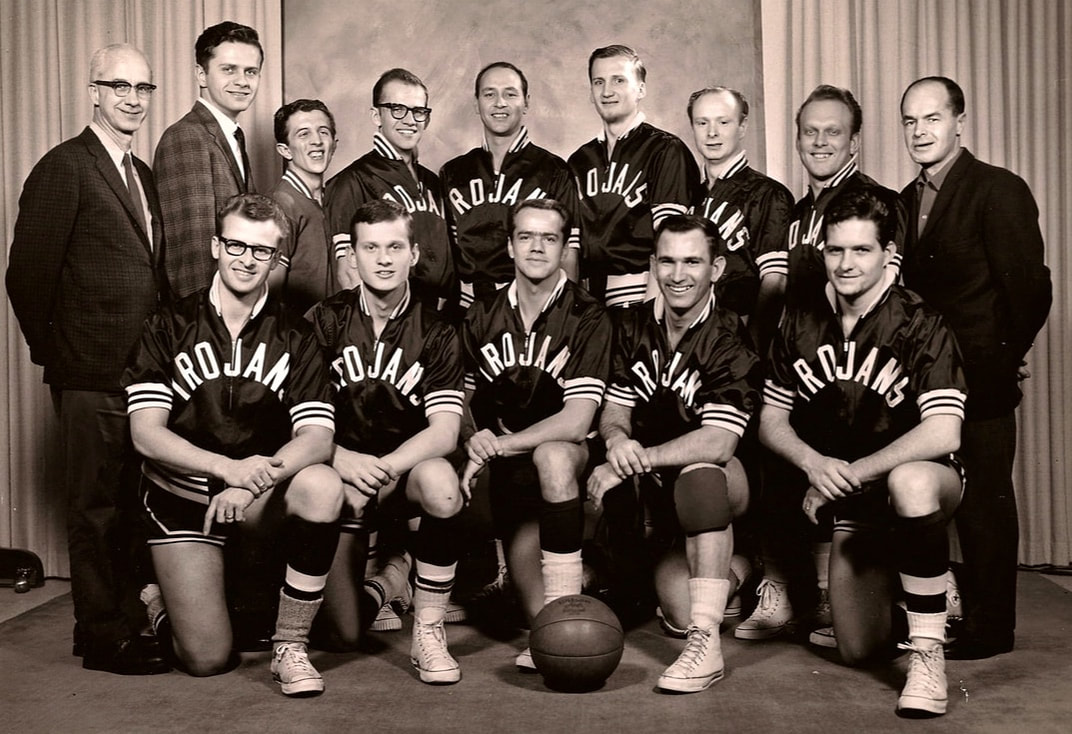

The Utah Athletics Club of the Deaf team at the Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf Tournament, pose with trophies in Philadelphia, Penn in 1964. Kneeling L-R: R. Per·kins, E. Bell, B. Harvey, R. Cochran, Standing, L-R:

L. Curtis, E. Pzybyla, N. Williams, R. Bonnell, J. Christensen, J. Murray, John F. White (asst. coach/manager)

1964 UCAD Basketball Team. District champs of Northern Athletic Association, pose with trophies: front from left, Roy Cochran, Roy Milborn, Carl Obson, middle: Bruce Harvey, Ronald Perkins, Leon Curtis, coach: Ed Bell, John White, manager: back, Norman Williams, Robert Bonnell, Jay Christensen, Eric Przybyla, and John Murray. The UAD Bulletin, February 1964

The Incorporation of the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf into the Utah State Laws

In 1970, the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf was incorporated under Utah law. It is now affiliated with several regional and national organizations and actively promotes numerous Deaf sports in Utah. The UACD sports program eventually added softball, volleyball, flag football, golf, and skiing/snowboarding.

The Utah Athletics Club of the Deaf team at the Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf Tournament, pose with trophies in Philadelphia, Penn in 1964. Kneeling, L-R: R. Perkins, E. Bell, B. Harvey, R. Cochran, Standing, L-R: Leon Curtis, E. Przybyla, N. Williams, R. Bonnell, J. Christensen, J. Murray, John F. White (asst. coach/manager)

Presidential Awards Given

to Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf

to Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf

On September 27, 1997, Nancy O'Brien chaired the 50th anniversary event at the Ramada Inn in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah. The ceremony featured the presentation of five Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf sportspeople's awards. Additionally, the Utah Association for the Deaf honored the sports club's 50-year history by presenting them with a Presidential Award, which UACD secretary Nancy O'Brien accepted.

In 2002, the Utah Association for the Deaf presented the UACD women's basketball team with the President's Award for outstanding performance at the USA Deaf Basketball National Basketball (USADB) Tournament in Indianapolis, Indiana. This was the first time a Utah women's basketball team had competed in the national tournament (UAD Bulletin, May 2002). Andrea Garff Anderson, a 1995 graduate of the Idaho School for the Deaf and basketball player for the UACD women's basketball team, accepted the award on their behalf (UAD Bulletin, September 2002).

President Justin Anderson of the

Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf Shares a Vision

Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf Shares a Vision

My vision is to keep the legacy of strong and rich history of Utah Athletic to carry on and pass the traditions and success to the new leaders and athletes.

We want to keep the name of the oldest active Deaf athletic club in the USA.

We want to have a strong amateur sport organization for the Deaf people, especially for the youth.

We want to keep the name of the oldest active Deaf athletic club in the USA.

We want to have a strong amateur sport organization for the Deaf people, especially for the youth.

In conclusion, John "Jack" White has primarily led the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf, making significant contributions beyond sporting events. Under Jack's leadership, the UACD has thrived for as long as it has. This organization has brought athletes together to stay healthy and meet and connect with other Deaf individuals. Deaf sports have played an essential role in developing the Utah Deaf community.

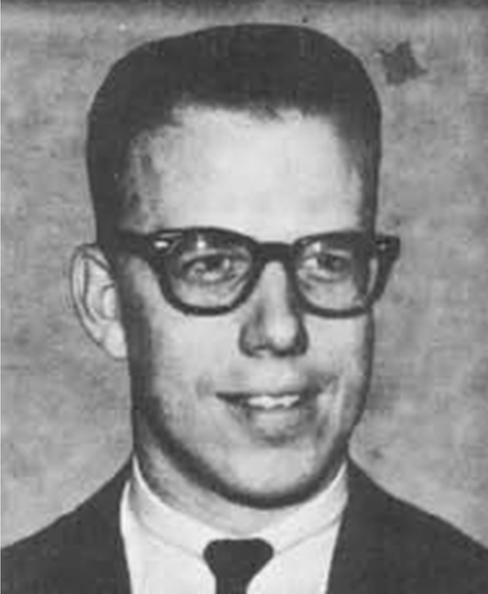

Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf

Discussions about the Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf (GSACD) took place in the locker room of the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, in the fall of 1971. After spending several years with the Utah Sports Club of the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, a group of basketball players explored starting their own athletic club in the Ogden region. By commuting to Salt Lake City and back to Ogden, a new club in Ogden would save time and money for Ogden players. G. Leon Curtis and Dennis Platt founded the club. Dennis suggested that a new club be named Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf (GSACD) for the region where Ogden was under the Golden Spike Empire (Tenth Anniversary Celebration Program Book; Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf: 25th Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

The first meeting was held at the Weber County Library on January 20, 1972, where C. Roy Cochran was elected as the organization's first president, followed by Ronald Johnston as vice president, Dennis Platt as secretary, and Tom Starkey as treasurer. On the first night, they raised $25.00. (Tenth Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

GSACD, like the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf, became one of the most well-known clubs in the NorthWest Athletic Association of the Deaf (NWAAD) region, which includes Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Washington State, Northern California, western Canada, including Vancouver, B.C., and Edmonton (Tenth Anniversary Celebration Program Book). GSACD was also a long-standing member of the American Athletic Association of the Deaf.

GSACD hosted various events for its members, including horseshoe, volleyball, softball, and golf competitions. For many years, club members, both men and women, competed in the Ogden City softball league to prepare for the annual NWAAD softball tournament (Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf 25th Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

GSACD, like the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf, became one of the most well-known clubs in the NorthWest Athletic Association of the Deaf (NWAAD) region, which includes Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Washington State, Northern California, western Canada, including Vancouver, B.C., and Edmonton (Tenth Anniversary Celebration Program Book). GSACD was also a long-standing member of the American Athletic Association of the Deaf.

GSACD hosted various events for its members, including horseshoe, volleyball, softball, and golf competitions. For many years, club members, both men and women, competed in the Ogden City softball league to prepare for the annual NWAAD softball tournament (Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf 25th Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

The UACD hosted the 1974 NWAAD softball tournament when the NWAAD established a new sport, softball. GSACD advanced to the finals and faced defending champion Seattle but lost and had to settle for second place (Tenth Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

GSACD, a pillar of our community, proudly hosted five Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf tournaments. These were held in 1978, 1986, 1992, and 1996 for softball and 1980 for basketball, marking significant milestones in our club's history (Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf 25th Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

GSACD lost the first game of the 1980 basketball tournament to Sacramento, 57-54, despite Nathaniel Cannon's 40 points. It was the tournament's highest score. After that, GSACD took home the consolation trophy (5th place). Nathaniel Cannon scored 92 points in the tournament games for GSACD, earning him a spot on the First Team NWAAD All-Star team. He was one vote away from being named MVP of the tournament (Tenth Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

GSACD, a pillar of our community, proudly hosted five Northwest Athletic Association of the Deaf tournaments. These were held in 1978, 1986, 1992, and 1996 for softball and 1980 for basketball, marking significant milestones in our club's history (Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf 25th Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

GSACD lost the first game of the 1980 basketball tournament to Sacramento, 57-54, despite Nathaniel Cannon's 40 points. It was the tournament's highest score. After that, GSACD took home the consolation trophy (5th place). Nathaniel Cannon scored 92 points in the tournament games for GSACD, earning him a spot on the First Team NWAAD All-Star team. He was one vote away from being named MVP of the tournament (Tenth Anniversary Celebration Program Book).

GSACD eventually became a place for families and athletes to socialize and have fun. This club had two goals: physical activities and sports for people of all ages. Attending an ice hockey game, tubing, roller skating, bowling, playing volleyball, basketball, softball, swimming, and camping were among the monthly activities available. In addition, picnics, holiday parties, and movie screenings were some of the activities that the club members participated in.

Wasatch Golf Association of the Deaf

The Wasatch Golf Association of the Deaf (WGAD) came into existence on September 13, 1980, at Schneiter's Riverside Golf Course in Ogden, Utah. "Why don't we establish a deaf club for golf?" One day, George Wilding proposed to his friends Robert DeSpain, Dennis Platt, and Fred Bass. That was something they all agreed on right away.

The goal of forming this organization was to capture the interest of the Utah Deaf community in golf. The monthly golf outings took place at various golf holes in northern Utah, the Salt Lake area, and Eagle Mountain.

The Robert G. DeSpain Memorial Tournament is named after Robert G. DeSpain, one of the WGAD's co-founders. Anyone can join the WGAD for fun, but players must play five rounds with a WGAD member to qualify for the Robert Despain Memorial Tournament.

WGAD organized the tournaments, and competitors also competed in the DeafNation Golf Classic for a chance to win a reward.

The goal of forming this organization was to capture the interest of the Utah Deaf community in golf. The monthly golf outings took place at various golf holes in northern Utah, the Salt Lake area, and Eagle Mountain.

The Robert G. DeSpain Memorial Tournament is named after Robert G. DeSpain, one of the WGAD's co-founders. Anyone can join the WGAD for fun, but players must play five rounds with a WGAD member to qualify for the Robert Despain Memorial Tournament.

WGAD organized the tournaments, and competitors also competed in the DeafNation Golf Classic for a chance to win a reward.

16th Winter Deaflympics in Utah

The 16th Winter Deaflympics took place in Utah from February 1 to 10, 2007. The United States Deaf Sports Federation (USADSF) selected Utah as the host for the Deaflympics for three reasons: firstly, the availability of world-class winter sports competition venues; secondly, Utah's reputation for having the best snow on earth; and lastly, an excellent pool of enthusiastic Deaf and hearing communities (Ingham, 2007).

The Winter Deaflympics is the world's second-oldest international sporting event, having begun in 1924. Two years before the hosting of the Deaflympics in 2007, at a press conference at Governor' Jon Huntsman, Jr.'s Mansion of Utah, Dr. I. King Jordan, president of Gallaudet University and honorary co-chairperson of the 16th Winter Deaflympics, stated athletes are not allowed to participate in the Paralympics because they are considered able-bodied under Olympic Committee rules. However, communication barriers prevent them from fully participating in the able-bodied Olympics (Jarvik, Deseret News, February 17, 2005).

Jeff Pollock, a snowboarder who has participated in several Deaflympic events, explained in 2005 that being a Deaf athlete in competitions like ski racing and ice hockey is challenging. This is because they can't hear the referee's whistle or the starting gun that signals them to exit the gate. At the Deaflympics, athletes are guided by flashing lights, hand signals, and flags. Jeff also noted that Deaf athletes face physical hurdles in tournaments such as what some refer to as "the hearing Olympics." He described being a Deaf snowboarder in a race with hearing racers as "lonely" (Jarvik, Deseret News, February 17, 2005).

Jeff Pollock, a snowboarder who has participated in several Deaflympic events, explained in 2005 that being a Deaf athlete in competitions like ski racing and ice hockey is challenging. This is because they can't hear the referee's whistle or the starting gun that signals them to exit the gate. At the Deaflympics, athletes are guided by flashing lights, hand signals, and flags. Jeff also noted that Deaf athletes face physical hurdles in tournaments such as what some refer to as "the hearing Olympics." He described being a Deaf snowboarder in a race with hearing racers as "lonely" (Jarvik, Deseret News, February 17, 2005).

The Deaf community values the Deaflympics highly. Edward Ingham, Secretary-General of the Organizing Committee at the time, lived in Utah. He stated that "the Deaflympics, along with the World Federation of the Deaf Congress, are the two largest international events for the Deaf, fostering international connections through the exchange of interests and experiences." Unlike those who attend international events and need interpreters, participants in international deaf events can communicate with one another without any difficulty. This is because their national sign languages have distinct linguistic characteristics. As a result, those who attend the Deaflympics and the World Federation of the Deaf Congress form strong friendships due to the ease of communication and shared experiences (Ingham, 2007).

At that time, the 16th Winter Deaflympics Board of Directors appointed Dr. Robert G. Sanderson and Ronald C. Burdett, both residents of Utah. In addition, Utah Deaf residents Dennis and Shirley Platt, Valerie Kinney, Eleanor "Eli" McCowan, Wendy Osterling, Justin Anderson, Jonathon Hodson, Scott and Adele Sigoda, Keith Mischo, Susan Stokes, and Barbara Bass, all Deaf volunteers, joined the committee to complete the task.

At the 16th Winter Deaflympics in Utah, 400 participants representing 25 countries competed in various sign languages. According to Jeff Pollock, the athletes used International Sign Language, a blend of numerous signs and motions from different signed languages, so communication hurdles were minimal (Jarvik, Deseret News, January 31, 2007). Representatives from all over the world competed for gold, silver, and bronze medals in five of the most popular winter sports: Alpine skiing, snowboarding, cross-country skiing, ice hockey, and curling, according to Ben Soukup, chairman of the 16th Winter Deaflympics Board of Directors. He described it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the world's best Deaf athletes to compete for world-class status (Soukup, 2007).

Utah had the honor of hosting the 16th Winter Deaflympics, where they displayed their famous "Greatest Snow on Earth." Salt Lake City made history by becoming the first city in the world to hold all three International Olympic Committee-sanctioned games, including the Olympics, Paralympics, and Deaflympics. The Deaflympics were an unforgettable event that left a positive impression on visitors from all over the world.

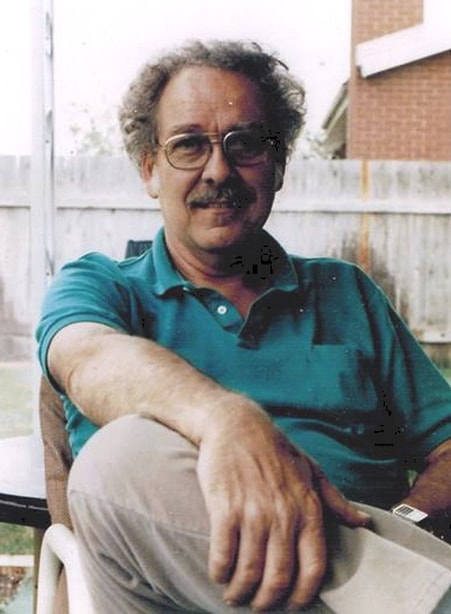

Dennis Platt as Torchbearer

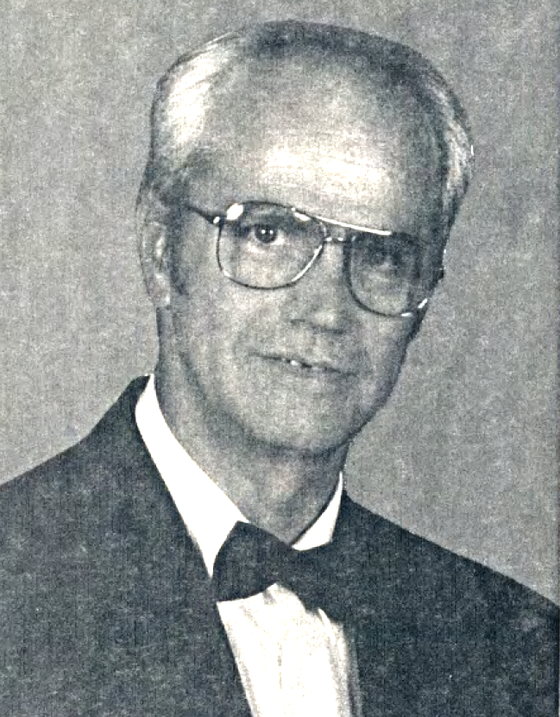

In 1996, a panel of community leaders from Ogden and Weber County selected Dennis Platt to carry the Olympic Flame. Dennis was a well-known leader in the Utah Deaf community and had long served as an officer of the American Athletic Association of the Deaf (AAAD). He was chosen out of 5,500 people who were considered for the role of a torchbearer because he met four key judgment criteria set by the Ogden region.

- Outstanding volunteer work,

- Community leader, role model, or mentor,

- His numerous acts of generosity or kindness have touched the lives of many, and he has achieved extraordinary feats or accomplishments, either locally or nationally (UAD Bulletin, February 1996; Shirley Platt, personal communication, January 6, 2015).

On May 10, 1996, Dennis carried the Olympic torch from 34th to 37th Streets on Washington Boulevard in Ogden, Utah. This brought the Olympic spirit to the Deaf community in the area. During this time, his granddaughter, Marissa Tarbet, flew the Olympic flag in front of the American Athletic Association of the Deaf (AAAD) offices on 36th Street (UAD Bulletin, July 1996, p. 11).

Dennis has shown a high level of dedication to the AAAD by providing many voluntary services to the organization. As a result, in 1999, Dennis was inducted into the AAAD Hall of Fame as a leader. Over the past twenty-five years, Dennis has served on AAAD committees and in various offices. His ongoing efforts have helped turn the AAAD into a powerful, dynamic national organization that benefits Deaf athletes who participate in AAAD sports events (UAD Bulletin, December 1999, p. 5). Some of his many contributions to the AAAD include:

Dennis has shown a high level of dedication to the AAAD by providing many voluntary services to the organization. As a result, in 1999, Dennis was inducted into the AAAD Hall of Fame as a leader. Over the past twenty-five years, Dennis has served on AAAD committees and in various offices. His ongoing efforts have helped turn the AAAD into a powerful, dynamic national organization that benefits Deaf athletes who participate in AAAD sports events (UAD Bulletin, December 1999, p. 5). Some of his many contributions to the AAAD include:

- AAAD Vice President of NSOs (1991-1994)

- AAAD Vice President for Financial Affairs (1994 – 1997)

- AAAD Ad Hoc Committee to establish women’s softball

- AAAD Restructuring Committee

- AAAD Law Committee member (eight years)

- AAAD Board of Director member (1980 – 1997

- AAAD Basketball/Softball Commissioner

- AAAD Regional President’s Round Table (three years)

- AAAD Grants and Planning Committee member

- AAAD Audit Committee member

- AAAD Games Preparation Committee member

During the difficult restructuring period, when many National Sports Organizations (NSOs) faced "banned" status and the AAAD's finances were in jeopardy, Dennis played a crucial role in the organization. Instead of taking opposing political positions, he discreetly continued the organization's "housekeeping" duties, completing the tasks necessary to keep the organization running while others were in the spotlight supporting one political agenda or the other (UAD Bulletin, December 1999, p. 5). Dennis was also a leader in the Northwest Association of the Deaf (NWAAD). Between 1978 and 1997, he served as the recording secretary, president, and chairman of two regional basketball tournaments and one regional softball tournament. He was the first person in any region to use computers to record tournament results. He received the NWAAD Hall of Fame induction in 1990 (UAD Bulletin, December 1999, p. 5). After twenty-eight years of dedicated service to Deaf sports, Dennis retired in 2002 (Shirley Platt, personal communication on January 6, 2015). The Utah Deaf community was fortunate to have Dennis's outstanding leadership in the sports field.

Dennis deserves recognition for his extensive history of voluntary contributions to organizations like the American Athletic Association of the Deaf, the Northwest Association of the Deaf, and the Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf. He always approaches his work with humility and a low-key demeanor. Apart from participating in sports organizations, he also served on multiple committees and in various offices for the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf's Ogden Division #127, the Utah Association for the Deaf, and the USDB Institutional Council. We owe Dennis a debt of gratitude for his selfless contributions to the Utah Deaf Community.

Utah Deaf Athletes

Marvin J. Marhall, Deaf Boxer

Marvin J. Marshall, a Deaf boxer, began his boxing journey in 1930. Despite facing challenges due to his hearing loss, he remained captivated by the sport and showcased his skills at various events across the country, such as county fairs, festivals, boys' clubs, and athletic shows. In 1936, he emerged victorious, winning the Utah Golden Glove 112-pound title. After he graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1942, he continued his boxing career at Gallaudet College, where he also took on the role of a coach for a group of Gallaudet boxers. After he graduated from Gallaudet College, he retired from boxing, firmly believing that a deaf person should always prepare before stepping into the boxing ring, as a single punch could potentially lead to the loss of an eye (Strassler, Recreation & Sports).

In the 1940s, Marvin won the local Golden Gloves boxing title and competed in the national Golden Gloves tournament in Washington, D.C. During his boxing career, he participated in approximately 500 amateur boxing fights. In 1995, the Gallaudet Athletic Hall of Fame inducted Marvin in recognition of his boxing achievements at Gallaudet College. Furthermore, in 2001, the USA Deaf Sports Federation Hall of Fame honored him for his athletic contributions (USDeafSports.org).

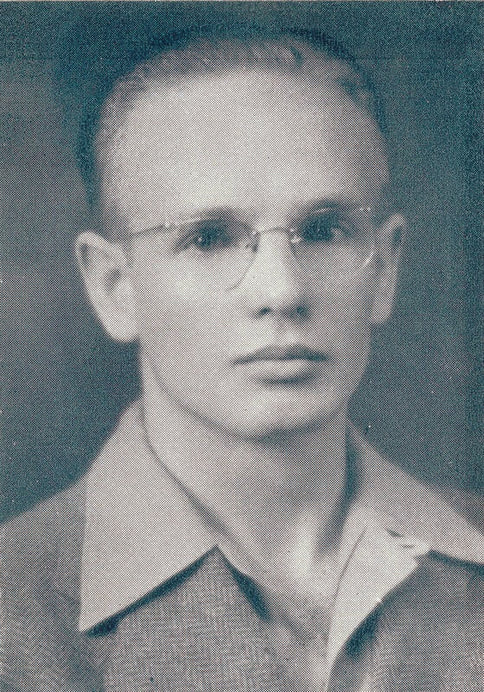

Paul Franklin Baldridge, Gallaudet's Athlete

Paul Franklin Baldridge was a Gallaudet athlete in the 1940s. He graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1938. Paul was a member of the famous "Five Iron Men" basketball team at Gallaudet College in 1943, and he served as team captain from 1942 to 1944. Paul was an exceptional athlete who lettered in various sports at Gallaudet College (GallaudetAthletics.com).

In 1944, he received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Gallaudet College. He was also a member and officer in several academic and social organizations. Paul graduated from the University of Arizona in 1953 with a Master of Education degree. He started a 46-year career as a teacher and coach at Gallaudet College, the Arizona School for the Deaf and Blind, the Missouri School for the Deaf, and the Indiana School for the Deaf. He influenced and inspired numerous young Deaf people during his career (Obituary: Paul Baldridge). In recognition of his coaching achievements, the American Athletic Association of the Deaf inducted Paul into its Hall of Fame in 1998 (GallaudetAthletics.com).