History of the Vocational Education Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2013

Updated in 2024

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2013

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

Since its inception in 1884, the Utah School for the Deaf has been a pioneer in introducing vocational education programs. These initiatives have been instrumental in equipping Deaf and hard of hearing students with the skills and trades necessary for a successful vocational career after graduation.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thanks for taking an interest in reading the 'History of the Vocational Education Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thanks for taking an interest in reading the 'History of the Vocational Education Programs at the Utah School for the Deaf' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Introduction of the

Vocational Education Programs

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Vocational Education Programs

at the Utah School for the Deaf

In 1889, four years after the establishment of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah in 1884, they introduced a vocational education program that included skills such as carpentry, shoe repair, printing, cooking, and sewing. This program aimed to not only equip Deaf and hard of hearing students with skills, but also empower them to contribute to society through various trades and skills, thereby making a significant societal impact. In addition to the vocational education program, students at the Utah School for the Deaf received a comprehensive education that included subjects such as arithmetic, advanced mathematics, physics, geography, history, art, and English. The school showed its commitment to a well-rounded education by offering students the opportunity to pursue occupational training at no additional cost, ensuring a balanced educational approach (Roberts, 1994).

Vocational Education Program Provides

Transition From Vocational Paths to Work

Transition From Vocational Paths to Work

The early students at the Utah School for the Deaf came from families with diverse occupations. The parents of rural students, for example, were mainly involved in farming or ranching (Roberts, 1994). John Beck, one of the founders of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1884 and a father of three Deaf sons, contributed to this diversity through his ownership of the Bullion-Beck Mine and Beck's Hot Springs. The fathers of the students had various occupations, such as farming, shoemaking, carpentry, and labor. Some were also butchers, merchants, accountants, mechanical engineers, county recorders, dentists, surveyors, candy makers, eye specialists, and postmasters (Evans, 1999).

The employment landscape for Deaf individuals used to be challenging. Many followed their parents' career paths, while others pursued different fields. However, things were changing. The Utah School for the Deaf started offering vocational education programs that equipped students with marketable skills and empowered them to transition from vocational to work-related coursework. This training helped students achieve self-sufficiency, opening up more job opportunities for them after graduation. While many students chose to specialize in a particular field, they didn't always end up working in that specific area they studied for (Robert, 1994).

After graduating from high school, many young men and women choose to live and work in the metropolitan districts of Salt Lake City or Ogden. These areas, with their large Deaf communities, not only offer job opportunities but also provide a strong sense of belonging and understanding. This sense of community is often lacking in the isolation of a small town in Utah with few other Deaf people (Roberts, 1994).

After graduating from high school, many young men and women choose to live and work in the metropolitan districts of Salt Lake City or Ogden. These areas, with their large Deaf communities, not only offer job opportunities but also provide a strong sense of belonging and understanding. This sense of community is often lacking in the isolation of a small town in Utah with few other Deaf people (Roberts, 1994).

Did You Know?

"For a young school ours had a right to feel proud of its graduates, all of whom were respectable, industrious, and self-supporting citizens. We had among nineteen graduates, one surveyor, one teacher, two instructors, one photographer, four farmers, three housewives, two carpenters, one printer, one student, and three laborers." ***** Utah Eagle (The Silent Worker, June 1906).

The Expansion of the

Vocational Education Program for Boys

Vocational Education Program for Boys

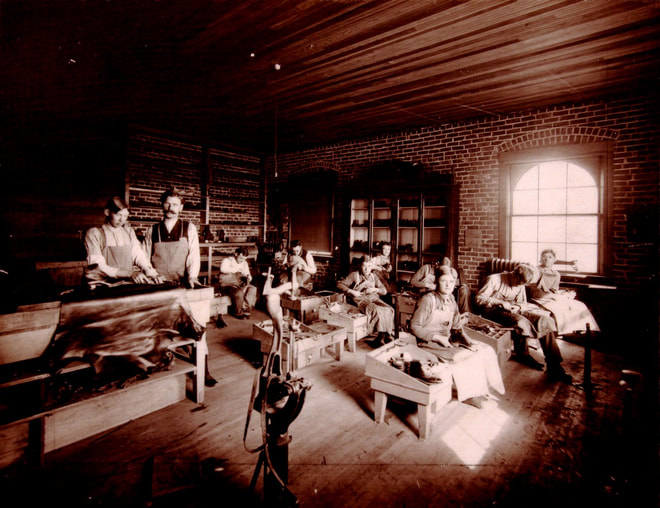

Since its establishment in 1889, the Utah School for the Deaf has provided a wide range of classes through its vocational education program. Initially, the school offered printing, shoemaking, and carpentry classes for boys. Over time, the program expanded to include farming, gardening, blacksmithing, painting, and barbering, creating a diverse selection of vocational subjects (Roberts, 1994).

By the early 1900s, the Utah School for the Deaf had broadened its vocational education offerings even further. The curriculum included additional classes like leather crafts, mechanical drawing, upholstering, and photography. Boys in the first six grades had the opportunity to explore these various subjects, with the option to specialize in one during the final four years of high school. Graduates of this program experienced low unemployment rates (Utah School for the Deaf Program Book, 1960s).

By the early 1900s, the Utah School for the Deaf had broadened its vocational education offerings even further. The curriculum included additional classes like leather crafts, mechanical drawing, upholstering, and photography. Boys in the first six grades had the opportunity to explore these various subjects, with the option to specialize in one during the final four years of high school. Graduates of this program experienced low unemployment rates (Utah School for the Deaf Program Book, 1960s).

Printing

The printing department at the Utah School for the Deaf, staffed by talented and dedicated students, produced school magazines such as the 'Deseret Eagle,' 'Eaglet,' and 'Utah Eagle.' These students not only worked as printers, but they also served as "historians," documenting the lives and events of the school and the Utah Deaf community. Additionally, they printed various documents for the school administration and the Utah Association of the Deaf, showcasing their valuable contributions (The Utah Eagle, September 15, 1897).

On October 10, 1889, the printing department released its first issue of "The Deseret Eagle," a small publication. The printing department published this paper every two weeks until it ceased in 1894. The printing students then took over and created, edited, and published the second paper, "The Eaglet," from 1894 to 1899. This marked a transition in the department's operations. The "Deseret Eagle" ran for three years before the "Utah Eagle" emerged on March 1, 1897. The word "Utah" replaced "Deseret" in this publication soon after Utah became a state in 1896. The early pioneers who came to the state called it "Deseret," which means "industry" in the Book of Mormon. Since then, the superintendent and his staff have edited "The Utah Eagle," which served as the school's official magazine. During the school year, the publication changed to once a month. These magazines provided the Utah Deaf community with recent events that were important to them. They also contained daily updates on student activities, staff members, student and family information, and news from other Deaf organizations and schools (The Utah Eagle, September 15, 1897; Pace, 1946; Roberts, 1994; Utah School for the Deaf Program Book, 1960s).

Harry Sanger Smith, Known as “Bob White”

In The Silent Worker Magazine

In The Silent Worker Magazine

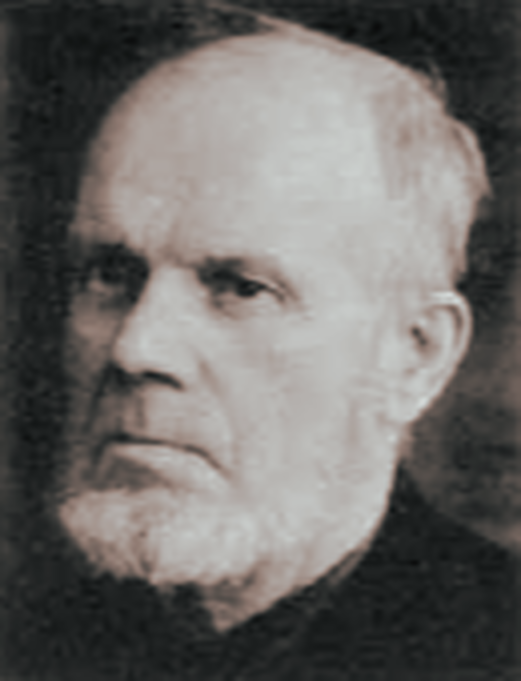

Harry Sanger Smith was a remarkable individual who became the first printing and linotyping instructor at the Utah School for the Deaf. He was born in Rosemount, New Jersey, on July 12, 1877. At the age of 12, he lost his hearing to cerebrospinal meningitis and pneumonia. Despite this significant challenge, he persevered and achieved remarkable success in the field of printing.

After losing his hearing, he enrolled in the New Jersey School for the Deaf because he couldn't finish his education in a regular school (The Silent Worker, September 1900). As an exceptionally bright student, Mr. Porter assigned him to the printing office, where he learned basic typesetting and presswork. Harry initially objected, arguing that he had to master the entire type case before setting the type. He said that where he lived, he "constructed pig pens for a dollar a day." Mr. Porter convinced him that if he learned to print, he could make more money. As a result, he decided to stay (The Silent Worker, April 1925).

Harry was unwaveringly dedicated to his printing skills. After graduating from the New Jersey School for the Deaf, he promptly secured a printing job in Trenton, New Jersey, where he worked for five years. His typographical executions were so impeccable that they caught the attention of his peers. He joined the Typographical Union and spent his spare time honing his skills, demonstrating his commitment and passion for his work.

By this time, Harry had become tired of his job and relocated to New Hope, Pennsylvania, to take over the management of a country weekly. Two months later, Harry accepted a job as an advertising composer at one of Philadelphia's most prominent establishments. The office employed roughly 200 employees and had seventeen cylinder presses, nine linotypes, its own lighting facility, an electrotype foundry, and an ink factory (The Silent Worker, September 1900).

He moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado, due to his passion for the outdoors, particularly fishing and hunting. He combined printing with camping, hunting, trapping, fishing, and penning adventure stories for magazines such as The Silent Worker (The Silent Worker, April 1925). He published several articles in the Silent Worker magazine, including "Bob White" (The Silent Worker, September 1900). In 1920, Harry traveled through Utah's Ogden Canyon in his Deaf friend Paul Mark's Peerless car with National Fraternal Society of the Deaf President H.C. Anderson (The Silent Worker, November 1920).

After losing his hearing, he enrolled in the New Jersey School for the Deaf because he couldn't finish his education in a regular school (The Silent Worker, September 1900). As an exceptionally bright student, Mr. Porter assigned him to the printing office, where he learned basic typesetting and presswork. Harry initially objected, arguing that he had to master the entire type case before setting the type. He said that where he lived, he "constructed pig pens for a dollar a day." Mr. Porter convinced him that if he learned to print, he could make more money. As a result, he decided to stay (The Silent Worker, April 1925).

Harry was unwaveringly dedicated to his printing skills. After graduating from the New Jersey School for the Deaf, he promptly secured a printing job in Trenton, New Jersey, where he worked for five years. His typographical executions were so impeccable that they caught the attention of his peers. He joined the Typographical Union and spent his spare time honing his skills, demonstrating his commitment and passion for his work.

By this time, Harry had become tired of his job and relocated to New Hope, Pennsylvania, to take over the management of a country weekly. Two months later, Harry accepted a job as an advertising composer at one of Philadelphia's most prominent establishments. The office employed roughly 200 employees and had seventeen cylinder presses, nine linotypes, its own lighting facility, an electrotype foundry, and an ink factory (The Silent Worker, September 1900).

He moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado, due to his passion for the outdoors, particularly fishing and hunting. He combined printing with camping, hunting, trapping, fishing, and penning adventure stories for magazines such as The Silent Worker (The Silent Worker, April 1925). He published several articles in the Silent Worker magazine, including "Bob White" (The Silent Worker, September 1900). In 1920, Harry traveled through Utah's Ogden Canyon in his Deaf friend Paul Mark's Peerless car with National Fraternal Society of the Deaf President H.C. Anderson (The Silent Worker, November 1920).

In 1923, when the union went on strike, Harry, a staunch supporter of unionism, stood in solidarity with the strikers. After a prolonged strike, the Utah School for the Deaf convinced him to join as their printing and linotyping instructor. Relocating to Ogden, Utah, he embarked on a role with one of the finest printing offices in the West (The Silent Worker, April 1925). His dedication and skill elevated the standard of the 'Utah Eagle' magazine, making it a typographical masterpiece during his tenure (The Silent Worker, May 1924). The superintendent of USDB, Frank M. Driggs, not only recognized but also celebrated Harry's artistic talent, stating, "Never in the history of printing has a printer been so splendid, so thorough, and so dedicated to his work and his printer boys." In the shop, he, Harry, guided them and had a remarkable influence over them (The Silent Worker, May 1925).

Harry's reputation as a skilled printer was well-established. In the summer of 1925, he was chosen by the Chairman of the Industrial Section to present a paper at the convention of Principals and Superintendents of the Deaf in Cincinnati, Ohio. However, tragedy struck on March 2 of that year when Harry passed away suddenly from acute gastritis. He was laid to rest in the Ogden City Cemetery, just a block away from the school gate (The Silent Worker, April 1925). Harry's talent for writing led him to the office of the Silent Worker, where he learned about the mysteries of the printers' art and was persuaded to give up his plan to build pig pens for a dollar a day (The Silent Worker, May 1924).

Harry's reputation as a skilled printer was well-established. In the summer of 1925, he was chosen by the Chairman of the Industrial Section to present a paper at the convention of Principals and Superintendents of the Deaf in Cincinnati, Ohio. However, tragedy struck on March 2 of that year when Harry passed away suddenly from acute gastritis. He was laid to rest in the Ogden City Cemetery, just a block away from the school gate (The Silent Worker, April 1925). Harry's talent for writing led him to the office of the Silent Worker, where he learned about the mysteries of the printers' art and was persuaded to give up his plan to build pig pens for a dollar a day (The Silent Worker, May 1924).

William “Bill” Cole,

An Ogden Standard-Examiner Typographer

An Ogden Standard-Examiner Typographer

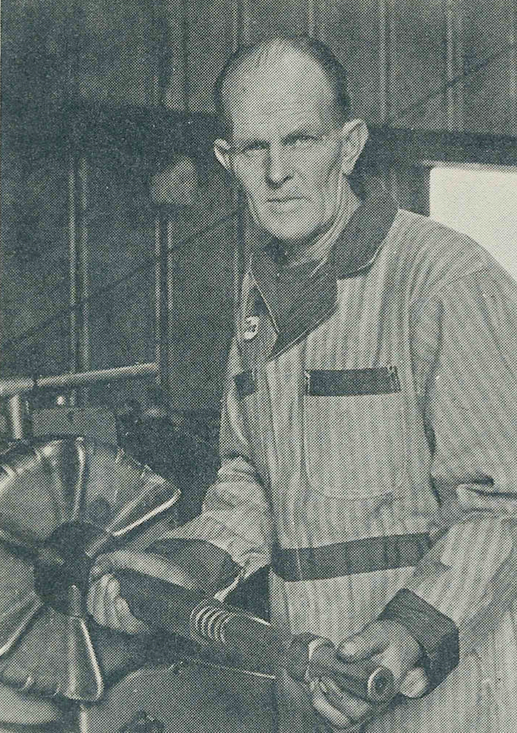

The first Deaf printer, William "Bill" Cole, faced and overcame significant challenges in his career. Born on June 15, 1884, in England, he experienced the harsh reality of life when his father tragically died in a coal mine accident in 1904. Despite this devastating loss, he bravely left the Utah School for the Deaf, where he had been a student since 1897, to support his family. His career in the printing industry began on April 10, 1912, when he started as a galley boy at the old Ogden Standard. The industry was in a state of upheaval due to the merger of Ogden's two major newspapers, the "Standard" and the "Examiner." However, Bill's unwavering determination and his skill as one of the city's fastest "makeup men" ensured his continued employment, highlighting his ability to overcome adversity (White, The Silent Worker, June 1920).

Bill's dedication to his printing skills was unparalleled. He worked as a typographer for the same company for fifty years, showcasing his commitment and talent. He is highly respected as one of the most experienced professionals in the industry, having served exclusively for one newspaper among typographers in the United States (UAD Bulletin, March 1984). He held various roles throughout his career, including "head setter," makeup artist, ad man, floor man, and shop foreman. On April 10, 1962, William retired from the company, leaving a legacy of perseverance and achievement. His deafness never hindered his success (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1962).

Bill's unique perspective was advantageous in his work. In a feature in Editor and Publisher in 1941, he shared the following:

"My Deafness is to my advantage. The noise in the composing room tends to distract some workers – but me. I never hear it. Thus, I am better able to keep my mind on my work."

Editor and Publisher commented:

"He is one of the fastest make-up men in the Intermountain country" (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1962).

Bill was well-liked by both his workplace and the Deaf community in Utah. After traveling around the country, he worked as a make-up artist and operator at the "Standard" (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920).

Bill's dedication to his printing skills was unparalleled. He worked as a typographer for the same company for fifty years, showcasing his commitment and talent. He is highly respected as one of the most experienced professionals in the industry, having served exclusively for one newspaper among typographers in the United States (UAD Bulletin, March 1984). He held various roles throughout his career, including "head setter," makeup artist, ad man, floor man, and shop foreman. On April 10, 1962, William retired from the company, leaving a legacy of perseverance and achievement. His deafness never hindered his success (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1962).

Bill's unique perspective was advantageous in his work. In a feature in Editor and Publisher in 1941, he shared the following:

"My Deafness is to my advantage. The noise in the composing room tends to distract some workers – but me. I never hear it. Thus, I am better able to keep my mind on my work."

Editor and Publisher commented:

"He is one of the fastest make-up men in the Intermountain country" (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1962).

Bill was well-liked by both his workplace and the Deaf community in Utah. After traveling around the country, he worked as a make-up artist and operator at the "Standard" (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920).

Many students were trained as printers, but only a few of them decided to pursue a career in the printing industry after graduation. Some notable printers from this group include William "Bill" Cole, George L. Laramie, Charles Roy Cochran, Keith Nelson, W. David Mortensen, and Kenneth L. Kinner. They each found success working for various newspapers such as the Ogden Standard-Examiner, the Salt Lake Tribune, The Deseret News, and the Newspaper Agency Corporation, showcasing their adaptability and versatility in the industry.

Some Deaf employees also briefly worked in the printing industry before finding other employment. For instance, Charles Martin worked for a newspaper in Nephi before resigning to return to his family's farm in southern Idaho, where he farmed for the rest of his life. John H. Clark, who graduated from the Utah School for Deaf Printing, received a bachelor's degree from Gallaudet College. However, upon returning to Utah, he decided to work in the construction and building industries instead of pursuing a career in printing (Robert, 1994). G. Leon Curtis worked in the printing industry before resigning to attend the University of Arizona to pursue a graduate degree (G. Leon Curtis, personal communication, February 7, 2009).

Kenneth L. Kinner, a Printer

for the Newspaper Printing Industries

for the Newspaper Printing Industries

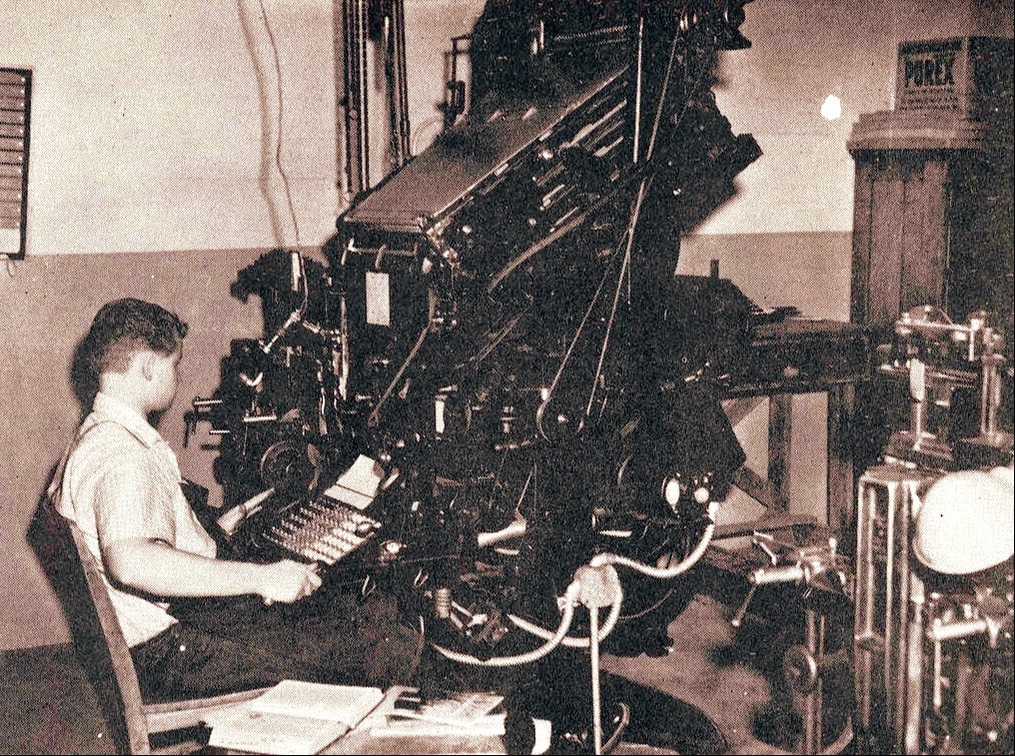

Kenneth L. Kinner, a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1954, went through various vocational training programs before deciding to pursue printing. At age 16, he secured a printing position at the Inland Printing Company in Kaysville, Utah. While studying at the USD, he continued to work as a printer until he graduated in 1954. He received an hourly wage of 75 cents during this time, which later increased to $2.00 per hour. In 1960, Kenneth relocated to Salt Lake City, Utah, and earned a salary of $3.00 per hour, which he considered an excellent wage. Using his earnings, Kenneth bought a new 1957 Ford car for $2,000, which cost him only $60.00 monthly for three years.

After graduation, Kenneth worked for the Inland Printing Company and lived with his mother in Clearfield, Utah. Despite his long work hours from 7:00 a.m. until 10:00 p.m. on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, he was dedicated and responsible. Kenneth proudly declared that he earned good money, which indicated his financial independence and success. Although he considered attending Gallaudet College, he decided against it because he realized that he would make the same pay as he did at the time, and that a college degree would not increase his earnings.

After graduation, Kenneth worked for the Inland Printing Company and lived with his mother in Clearfield, Utah. Despite his long work hours from 7:00 a.m. until 10:00 p.m. on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, he was dedicated and responsible. Kenneth proudly declared that he earned good money, which indicated his financial independence and success. Although he considered attending Gallaudet College, he decided against it because he realized that he would make the same pay as he did at the time, and that a college degree would not increase his earnings.

Kenneth L. Kinner, who married Ilene Coles in 1959, a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, worked at the Inland Printing Company. In 1960, he joined the Newspapers Agency Corp., working with two newspaper companies: The Salt Lake Tribune and The Deseret News. In 1964, Kenneth accepted a job offer with the Ogden Standard-Examiner, and they relocated to Ogden, Utah, so that their daughter Deanne, who was deaf, could attend Utah School for the Deaf. They bought their first home for $14,000 on Eccles Avenue between 30th and Patterson Streets and lived there for 23 years, paying $130.00 monthly. The company assigned Kenneth to work during the day, and he remained with them until 1993. Kenneth decided to retire due to downsized employers and significant technological advancements, but he continued to work part-time in 1994. Kenneth compared modern technology to an old dog learning new tricks, such as a computer taking over printing. He worked until he was 75 in 2008, marking 44 years in the printing profession (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, December 26, 2010). Kenneth was proud of his profession and loved telling stories about his experiences at the printing companies.

Teletype-setter recently installed at Inland Printing Company sets type automatically from a perforated tape. Kenneth L. Kinner, Inland Linotype operator watches as William G. McMahon, customer engineer for Fairchild Graphic Equipment Company, San Jose, California, checks first tape run through machine which is attached to one of the company's four type setting machines. The Reflex Journal, November 13, 1958

The following newspaper article provides information about Kenneth L. Kinner, his employment as a linotype operator, and his twin Deaf sister, Eleanor Kay Kinner, who worked as a model for clothing catalogs.

Blacksmith Trade

The Utah School for the Deaf taught its students blacksmithing skills and included the trade in its curriculum. Hugh Jacob, a Deaf student, spent most of his professional life working as a blacksmith in Heber City, Utah. Later, many residential schools included auto mechanics and machine shops where students could learn blacksmithing (Roberts, 1994).

Carpentry

The carpentry class, the first and most popular vocational class at the Utah School for the Deaf, saw significant growth after the school's move to Ogden, Utah, in 1896. A key figure in this expansion was Nephi Larsen, a Deaf carpentry graduate. Not only did he teach many students, but he also led carpentry workshops, contributing to the class's success. Under his guidance, the students learned to make frames, doors, windows, sashes, shelves, and tables, showcasing the effectiveness of vocational education for the Deaf (The Utah Eagle, September 15, 1897; Roberts, 1994).

The carpentry shop also played a crucial role in maintaining the school buildings on campus. Equipped with their newly acquired woodworking skills, students from the Utah School for the Deaf undertook numerous projects that contributed to the upkeep of the school buildings, ensuring they remained in good shape (The Utah Eagle, September 15, 1897).

The carpentry shop also played a crucial role in maintaining the school buildings on campus. Equipped with their newly acquired woodworking skills, students from the Utah School for the Deaf undertook numerous projects that contributed to the upkeep of the school buildings, ensuring they remained in good shape (The Utah Eagle, September 15, 1897).

Donald Jensen, a 1938 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, taught woodworking classes. After graduating from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1944, Lloyd H. Perkins worked as a carpenter in the construction industry. In 1977, he, then branch president and bishop of the Salt Salt Valley for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, designed and completed a deaf-friendly church for the Salt Lake Valley Deaf Ward.

Barbering

In 1896, the Utah School for the Deaf relocated to Ogden, Utah, marking a significant move in the school's history. As part of this new chapter, the school established a barbering program. This unique initiative aimed to prepare Deaf students for careers in the barbering industry. The barbershop, in addition to providing grooming services for students and staff, also served as a training ground. Former USD student Arvel Christensen is a shining example of the program's success, having gone on to open his own barbershop. Barbering provided students with an alternative skill to acquire while still in school. For example, Andrew Madsen, one of the students, learned carpentry and later became a barber when he returned to Ephraim, Utah (Roberts, 1994).

Arvel Christensen, A Barbershop Owner

Arvel Christensen celebrated his retirement from the barbering business with an open house in 1973. He is believed to be the only Deaf barber who can use scissors in Utah, where he owned a barbershop at 908 Washington Boulevard in Ogden.

Arvel, a man of remarkable resilience, graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1932. Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, he persisted in his search for work. Faced with limited opportunities, he took matters into his own hands and opened a barbershop. Before this, he honed his skills at Moler Barber College in Salt Lake City, Utah, and after just five months of training, he passed his state exam.

Arvel, a man of remarkable resilience, graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1932. Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, he persisted in his search for work. Faced with limited opportunities, he took matters into his own hands and opened a barbershop. Before this, he honed his skills at Moler Barber College in Salt Lake City, Utah, and after just five months of training, he passed his state exam.

Arvel established his first shop, a small yet significant establishment, on his parents' front porch on 13th Street in Ogden. This humble beginning marked the start of a business that would not only sustain him and his family but also become a part of the community's fabric. In 1940, he took a bold step by leasing a property on Washington Boulevard and building a business with residential quarters in the back. The location, just across the street from Ogden High School, one of the largest high schools in Utah, ensured a steady flow of customers, cementing Arvel's place in local business history.

Arvel and Berdean, a couple deeply committed to their craft, moved into their home at 908 Washington Boulevard after their marriage. They transformed their front porch into a barbershop, a testament to their dedication and entrepreneurial spirit. However, life took an unexpected turn when Arvel suffered a minor stroke in May 1973. With his heart condition, he felt that after 40 years of hard work, it was time to step back and enjoy the fruits of their labor (UAD Bulletin, November 1973).

Arvel and Berdean, a couple deeply committed to their craft, moved into their home at 908 Washington Boulevard after their marriage. They transformed their front porch into a barbershop, a testament to their dedication and entrepreneurial spirit. However, life took an unexpected turn when Arvel suffered a minor stroke in May 1973. With his heart condition, he felt that after 40 years of hard work, it was time to step back and enjoy the fruits of their labor (UAD Bulletin, November 1973).

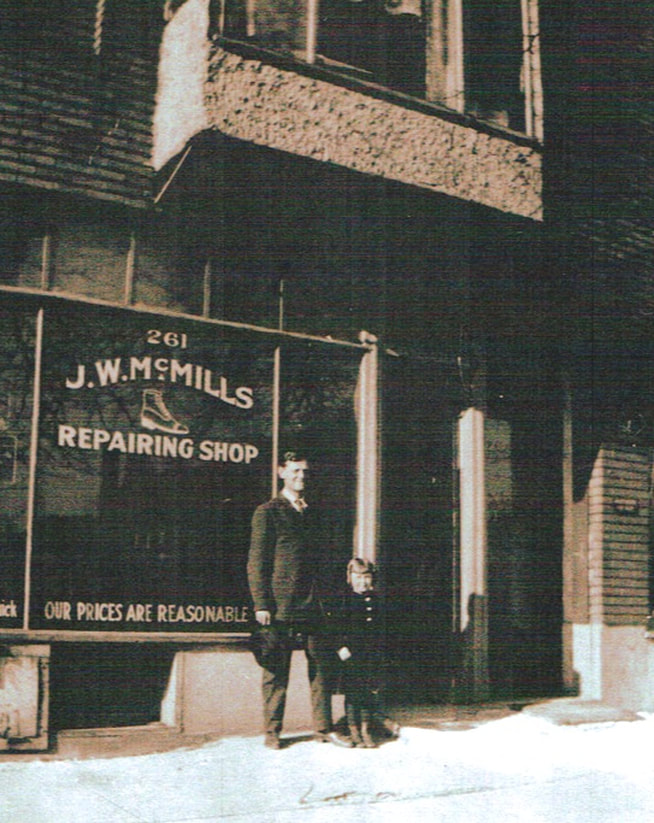

Shoemaking

The shoemaking program taught students how to make and repair shoes, and most of them went on to work in the shoe industry. The department also provided shoe repair services for students and employees (Roberts, 1994). Many students, including John Alvey, Paul Mark, John W. McMills, and Lee Shepherd, established their own shoe repair shops and worked in the shoe repair business throughout the state.

Paul Mark,

A Shoe Repair Shop Owner

A Shoe Repair Shop Owner

In the 1920s, Paul Mark, an 1892 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, owned "Dunn and Bradstreet," a shoe shop on 25th Street in Ogden, Utah. His business was thriving, and he even owned stock in several of Ogden's top industries (White, The Silent Worker, April and October 1920). When his business became too busy for him to handle alone, Cyril Jones, a fellow graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, stepped in. Cyril, a Deaf father of two Deaf sons, became Paul's assistant and later his full-time employee, marking the beginning of a successful partnership (White, The Silent Worker, June 1920).

If people in the Deaf community wanted to stay updated on the latest happenings, they would contact Paul Mark. He organized gatherings at his shoe shop, connecting Deaf individuals from the local community (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920). While Paul ran his shop in Ogden, Utah, another Deaf person, John W. McMills, who used to be a student at the Utah School for the Deaf, had a shoemaking and repair shop in Salt Lake City, Utah.

John W. McMills

A Shoe Repair Shop Owner

A Shoe Repair Shop Owner

At age six, in 1888, John Wallace McMills entered the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah. While in school, he learned a variety of trades. John excelled at horseshoeing, repairing, and fabricating harnesses. Shoemaking became his life's work. Following his father's health decline, John dropped out of school to become the primary breadwinner for the McMills family. His mother relied on him for a steady source of income. John, at the age of 20, opened his first shoemaking and repair shop in Tooele, Utah, around 1902. In 1903 or 1904, he moved his business to Mercur, Utah, to support his family. Following his marriage to Pearl Ault in 1910, John opened a new shop in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1926 and later relocated to San Francisco, California, to run his shoemaking business. Due to Pearl's health issues, he and their two daughters, Eva and Lucy, relocated to Utah to run his last business, J.W. McMills Shoe Repairing Co., located at 267 E. 5th South in Salt Lake City. John was well-known in the local business community. Furthermore, the Deaf community respected John and frequently sought his advice. In 1952, he retired and sold his business. In 1916, he was a founding member of Salt Lake City Division No. 56, an insurance company. John was a loving husband and father, and his family was his greatest source of joy and motivation.

Lee Shepherd,

An Owner of the Shoe Repair Business

An Owner of the Shoe Repair Business

In the early 20th century, Lee Shepherd's family moved to Spanish Fork, Utah. However, during the Great Depression, Lee's father moved the family to Salt Lake City in search of work. Lee was born in Salt Lake City in 1926, and the family moved back to Spanish Fork in 1928 after Lee became deaf. Despite the challenges of being a deaf student, Lee was determined and resilient. He enrolled in the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, in 1932. He graduated in 1946 as part of a small class of eight to ten students (Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009).

Lee's journey continued with his in-school apprenticeship training at the Utah School for the Deaf, which was a pivotal period in his life. Under the guidance of Paul Mark, a Deaf man who ran an Ogden shoe repair shop, Lee honed his skills. Paul Mark, a "weekend teacher," would come to the school campus on Fridays and Saturdays, dedicating his time to helping Lee and others learn the art of shoe repair. By his senior year, Lee's proficiency in the trade had earned him an invitation to teach and train other students, a testament to his dedication and talent. Lee's training also extended to Grant Morgan, a Deaf man who had a shoe repair shop in Spanish Fork. However, it was Paul Mark who played the most significant role in shaping Lee's future (Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009).

Lee's journey continued with his in-school apprenticeship training at the Utah School for the Deaf, which was a pivotal period in his life. Under the guidance of Paul Mark, a Deaf man who ran an Ogden shoe repair shop, Lee honed his skills. Paul Mark, a "weekend teacher," would come to the school campus on Fridays and Saturdays, dedicating his time to helping Lee and others learn the art of shoe repair. By his senior year, Lee's proficiency in the trade had earned him an invitation to teach and train other students, a testament to his dedication and talent. Lee's training also extended to Grant Morgan, a Deaf man who had a shoe repair shop in Spanish Fork. However, it was Paul Mark who played the most significant role in shaping Lee's future (Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009).

In March 1947, after working at the Modern Shoe Clinic in Ogden, Utah, Lee started his own business and established a shoe repair shop in Spanish Fork, Utah (Burdett, The Utah Eagle, January 1947). His first business, a testament to his hard work, was located in Spanish Fork, Utah, on the northwest corner of 100 North and 100 West, marking the beginning of his entrepreneurial journey. In 1956, he took a significant step forward by purchasing a larger and busier shop on the northeast corner of 200 North Main Street, demonstrating the growth and success of his business (Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009).

His sense of belonging deeply influenced Lee's decision to establish his business in Spanish Fork, Utah, rather than Ogden or Salt Lake City. He was already a recognized figure among his family, extended family, and the entire Spanish Fork community. He believed that this familiarity would help him build a clientele more easily. In contrast, he saw the larger and unfamiliar client base in Salt Lake City or Ogden as a potential challenge (Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009).

Lee's reputation in Spanish Fork was not only based on his kind demeanor and prompt service, but also on his significant contributions to the Deaf business community. In 1985, he sold his company and retired, having spent many years selling western boots and repairing shoes. He holds the distinction of being the final Deaf business owner to graduate from the Vocational Department of the Utah School for the Deaf. His influence extended beyond his business, as he also served on the boards of the Utah Association for the Deaf (Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009).

Lee's reputation in Spanish Fork was not only based on his kind demeanor and prompt service, but also on his significant contributions to the Deaf business community. In 1985, he sold his company and retired, having spent many years selling western boots and repairing shoes. He holds the distinction of being the final Deaf business owner to graduate from the Vocational Department of the Utah School for the Deaf. His influence extended beyond his business, as he also served on the boards of the Utah Association for the Deaf (Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009).

Thomas Loran Savage's Shoe Repair Business

in Flagstaff, Arizona

in Flagstaff, Arizona

While working at the Utah School for the Deaf, a pivotal institution that provided a transformative educational experience for Deaf individuals, in Ogden, Utah, Elizabeth "Libbie" DeLong, who graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1897 and Gallaudet College in 1902, met Thomas Loran Savage, also known as Loran Savage, from Antimony, Utah (Banks & Banks; Roberts, 1994). They spent a lot of time together and got to know each other well. Designed to foster a sense of community and independence among its students, the residential school environment at the time allowed students and staff members to interact, making it a popular social meeting spot for Deaf people, leading to several Deaf weddings (Roberts, 1994). Loran, who graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1914, was 14 years younger than Libbie. He was very athletic and participated in all of the school's sports, excelling as a basketball player. Loran was training to become a shoemaker (Banks & Banks). Loran and Libbie Savage married in Panguitch, Utah, on July 25, 1917. They later moved to Flagstaff, Arizona, where Loran started his own shoe repair business.

Loran and Libbie worked together at a shoe repair shop and had a great relationship. According to Banks and Banks, everyone in town held them in high regard. They were happy together until Libbie's final battle with cancer, which took her life in 1931 at the age of 57. Despite her illness, she maintained her cheerful demeanor, and Loran remained devoted to her. Libbie handled most of the office work for Loran (Banks & Banks).

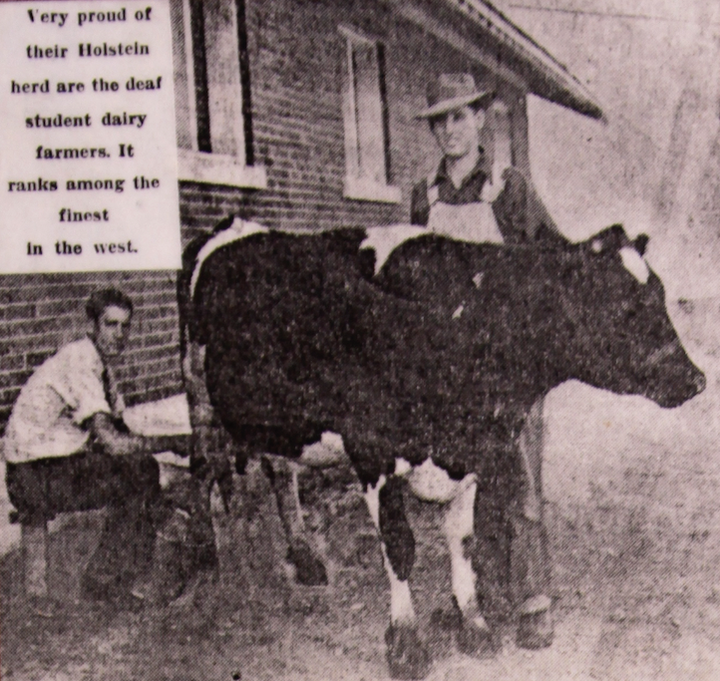

Learning Agriculture and Farming Skills

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

When the Utah School for the Deaf relocated to Ogden, Utah, in 1896, it occupied 200,000 acres of land on the school campus. The campus included lawns, flower beds, trees, orchards, a farm, and gardens. This extensive setup was not just for show; it was a self-sustaining ecosystem capable of growing crops and raising produce to feed the students (The Silent Worker, January 1897).

The Utah School for the Deaf provided more than just traditional classroom learning. It was a place where students acquired practical skills that would be valuable for their future. Under the guidance of skilled workers, they learned gardening, farming, and plant cultivation. This hands-on approach was intended to prepare students with the skills they would need to return to their agricultural heritage, demonstrating the school's commitment to practical education (The Silent Worker, January 1897).

The Utah School for the Deaf provided more than just traditional classroom learning. It was a place where students acquired practical skills that would be valuable for their future. Under the guidance of skilled workers, they learned gardening, farming, and plant cultivation. This hands-on approach was intended to prepare students with the skills they would need to return to their agricultural heritage, demonstrating the school's commitment to practical education (The Silent Worker, January 1897).

Did You Know?

"Mr. Driggs [USDB Superintendent] gave us ten dollars to deposit in the Commercial National Bank; we got a checkbook and when we buy chicken feed, we write a check to pay for it. When Mr. Driggs pays us for eggs, we deposit that money in the bank. When we have enough, we will pay back ten dollars to Mr. Driggs". – Utah Eagle

"No wonder they grow rich and prosperous out in Utah, when even the girls, in additions to learning poultry management in a practical, common-sense way, are given the excellent course in business methods which the above extract from a girl’s description of her poultry studies shows she is receiving" (The Silent Worker, November 1916).

"No wonder they grow rich and prosperous out in Utah, when even the girls, in additions to learning poultry management in a practical, common-sense way, are given the excellent course in business methods which the above extract from a girl’s description of her poultry studies shows she is receiving" (The Silent Worker, November 1916).

Gardening

The Utah School for the Deaf was able to start a horticulture program because of the size of the new facility in Ogden, Utah. The gardeners and staff members, Mr. Kremer and Mr. Hickenlooper, taught the students about agriculture and farming. Later, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints hired two students, Joseph Beck and Alfred Young, as gardeners at their 10-acre Temple Square in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah (Roberts, 1994).

Farming Animals and Tending Orchard

In 1897, the Utah School for the Deaf had a vast orchard with almost every type of fruit imaginable. The kitchen preserved the fruits and vegetables by canning and storing over 3,000 jars of fruit, several hundred quarts of jelly, pickles, tomatoes, chow-chow, ketchup, and other items (Roberts, 1994).

The boys learned about raising cattle and growing orchards. They also studied agriculture to improve their work skills, which would be helpful when they returned to their rural homes (Roberts, 1994).

The boys learned about raising cattle and growing orchards. They also studied agriculture to improve their work skills, which would be helpful when they returned to their rural homes (Roberts, 1994).

The Expansion of the

Vocational Education Program for Girls

Vocational Education Program for Girls

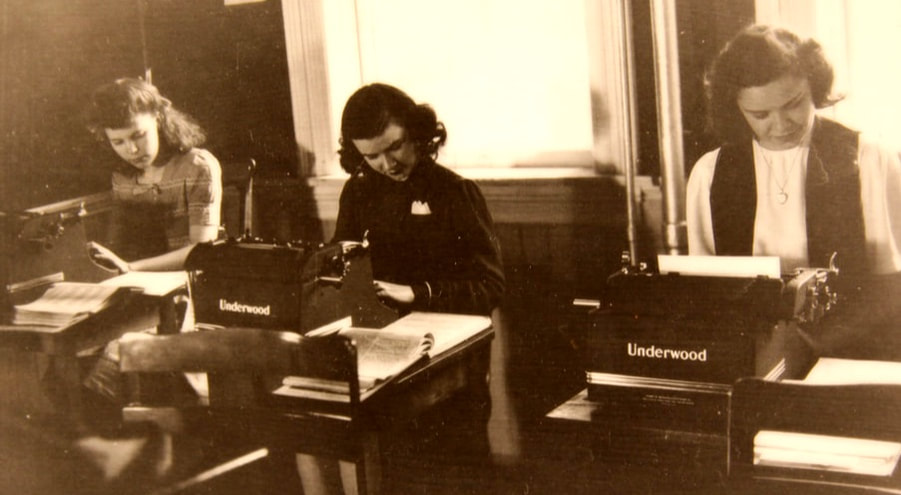

In 1897, girls at the Utah School for the Deaf received early education training, where they learned various homemaking skills such as embroidery, needlework, painting, crocheting, knitting, and making paper flowers. The homemaking class covered cooking, cleaning, and sewing. Additionally, the school provided instruction in commercial subjects, including typing, filing, and the proper use of office equipment (The Utah Eagle, September 15, 1897). During that time, the Utah School for the Deaf aimed to show that sending every Deaf child to this school would ensure their happy and content lives (The Utah Eagle, September 15, 1897).

During the first six grades at the Utah School for the Deaf, the vocational department for girls was the same as the school for boys. The girls learned how to cook, sew, make clothes, do fancy work, and clean the house (Driggs, The Utah Eagle, November 1, 1901). The girls also took regular housekeeping classes and helped with schoolhouse chores (The Utah School for the Deaf Program Book).

While both boys and girls participated in vocational education programs, they obtained equal experience. Several young women worked as dressmakers, including Sarah Abby and Ivy Griggs Low, who served as housemothers at the Montana School for the Deaf (Roberts, 1994).

Vocation Education Program Continued

at the Utah School for the Deaf in 1968

at the Utah School for the Deaf in 1968

The Utah Association of the Deaf has been a strong advocate for vocational education training. In 1968, while the vocational education programs at the Utah School for the Deaf were still operating, the UAD proudly recognized that Deaf students were more likely to enter society as productive, tax-paying citizens in a vocation rather than in a profession (The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

The vocational education program for girls in the 1960s included home nursing, family living, beauty culture, and data processing (The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

More Job Opportunities for the

Utah School for the Deaf Graduates

Utah School for the Deaf Graduates

The Utah School for the Deaf has been instrumental in helping students develop marketable skills, enabling them to lead independent lives and rely less on their families. Since its establishment in 1884, the school has contributed to the growth of the Utah Deaf community, fostering connections among its members in unprecedented ways. As a result, many graduates have chosen to live and work in metropolitan areas like Salt Lake City and Ogden rather than returning to the relative isolation of rural towns in Utah, where few other Deaf individuals resided after leaving the Utah School for the Deaf (Roberts, 1994).

More Trades and Skills Are Available

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

The vocational education program for boys in the 1960s witnessed a significant expansion, introducing a diverse range of trades and skills such as welding, sheet metal work, electrical and plumbing repair, and auto mechanics. This progressive approach, where students who met the school's requirements could utilize the facilities at Weber State College, marked a notable shift in vocational education (The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

The vocational education training for girls in the 1960s was designed to equip them with practical skills for their future roles. It included home nursing, family life, beauty culture, and data processing, all of which were considered essential for their societal contributions (The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

The vocational education training for girls in the 1960s was designed to equip them with practical skills for their future roles. It included home nursing, family life, beauty culture, and data processing, all of which were considered essential for their societal contributions (The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

Eleanor Kay Kinner works as a Card Punch Operator

at Hill Air Force Base, Utah

at Hill Air Force Base, Utah

In 1968, Eleanor Kay Kinner, a 1954 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, was recognized for her exceptional work as a card punch operator. This role, which involved meticulously punching holes in cards to create patterns for computer systems, was highly suitable for Deaf women. The noiseless environment allowed them to concentrate on the production process, making them efficient operators. Hill Air Force Base, the Internal Revenue Service, and the Western Service Center in Utah were among the many institutions that recognized the value of Deaf women in this role (The Utah Eagle, Summer 1968).

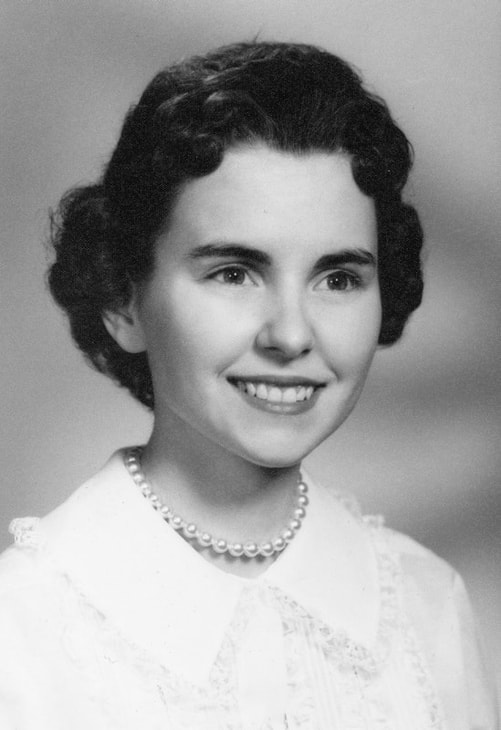

Ilene Coles Kinner

Detects Tax Fraud

Detects Tax Fraud

In 1976, Jim Hilber, a vocational rehabilitation counselor, set out to increase the number of Deaf employees at the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) in Ogden, Utah. Ilene Coles Kinner, a 1959 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, was among the eight Deaf individuals who helped Jim achieve this goal. Initially, she worked part-time to balance her work and family life. Fortunately, her exceptional skills as a tax examiner quickly came to light when she discovered fraudulent tax returns, preventing the disbursement of refunds amounting to $2,700. Her achievements not only showcased the abilities of Deaf individuals but also had a profound impact on the workplace, inspiring a new level of respect and inclusion.

Despite the seasonal nature of her job, Ilene remained dedicated and continued to work until May of that year. She then decided to stay at home with her son, Duane. However, her manager, Barbara Norseth, recognized Ilene's abilities and visited her home one summer day to offer her a full-time position. This was a significant decision for Ilene, as she was still figuring out how to balance work and her responsibilities as a mother. Jim and her manager unwaveringly supported and encouraged Ilene's determination to prove that Deaf people are capable of performing their jobs. She accepted the offer, becoming the first Deaf person to work full-time in a permanent position at the IRS.

Despite the seasonal nature of her job, Ilene remained dedicated and continued to work until May of that year. She then decided to stay at home with her son, Duane. However, her manager, Barbara Norseth, recognized Ilene's abilities and visited her home one summer day to offer her a full-time position. This was a significant decision for Ilene, as she was still figuring out how to balance work and her responsibilities as a mother. Jim and her manager unwaveringly supported and encouraged Ilene's determination to prove that Deaf people are capable of performing their jobs. She accepted the offer, becoming the first Deaf person to work full-time in a permanent position at the IRS.

In January 1978, Ilene Coles Kinner began working full-time. Her advocacy for hiring Deaf individuals for full-time, permanent positions was met with a positive response from the IRS, leading to the recruitment of more full-time Deaf employees. Ilene dedicated 26 years of service to the company before retiring on January 3, 2004. She found working for the Internal Revenue Service to be a fulfilling experience, and her gratitude towards the company for their responsiveness in hiring more Deaf employees was evident (Ilene Coles Kinner, personal communication, December 26, 2010).

Declination of the Vocational Education Programs

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

The Utah School for the Deaf has a long history of providing vocational education programs for Deaf and hard of hearing students, dating back to 1889. However, due to changes in educational priorities and the rise of mainstreaming, the vocational education programs at the school declined and ended in the 1990s. Now, students aged 16 to 21 can participate in the Supported Transition Extension Program, which offers comprehensive academic, social, job readiness, college preparation, and life skills education. Students who live on campus after high school can also gain independence, social skills, and adult transition skills. Additionally, the Ogden/Weber Applied Technology College provides trade certificates and on-the-job training for students, enabling them to work for various companies.

According to Michelle Tanner, Associate Superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf, the state has long advocated for all students to attend college. While many students find this helpful, others find it challenging. To ensure the success of all students, regardless of their goals, the Utah School for the Deaf made coordinated efforts a few years ago. These efforts were not made in isolation, but in collaboration with various institutions, reflecting our commitment to a comprehensive approach. Some students still want to attend college, while others prefer vocational education training. Under the Utah School for the Deaf's umbrella, the Kenneth Burdett School of the Deaf collaborates with Ogden-Weber Technical College (OTEC) in the Ogden area, offering job coaches and interpreters to make classes more accessible. Students at the Utah School for the Deaf have acquired welding and culinary arts degrees, with some graduating at the top of their classes. The school recently partnered with EnableUtah, a nonprofit organization in Ogden, to provide a career training program for students who have experienced major delays. The Utah School for the Deaf also transformed the old woodshop on the Ogden campus into a vocational training facility equipped to design and print shirts and work on technical projects. The school has also collaborated with Salt Lake Community College and Paul Mitchell Cosmetology School in Salt Lake City to help students obtain credentials from co-enrolled programs. Additionally, in the fall of 2019, the school hired a transition specialist to find businesses willing to train their students for various vocations. Despite changes in vocational education programs, the Utah School for the Deaf has established an approach to allow Deaf and hard of hearing students to pursue vocational education.

Despite changes in vocational education programs, the Utah School for the Deaf has established an approach to allow deaf and hard of hearing students to pursue vocational education.

Despite changes in vocational education programs, the Utah School for the Deaf has established an approach to allow deaf and hard of hearing students to pursue vocational education.

ARCHIVES

- Special Alumni Issue. The Utah Eagle, April 1955. (PDF)

- Utah Deaf People in Business and Industry...in the Space Age. The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1968. (PDF)

Notes

Doug Stringham, personal communication, April 29, 2009.

G. Leon Curtis, personal communication, February 7, 2009.

Ilene Coles Kinner, Personal Interview, December 26, 2010.

Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, December 26, 2010

Michelle Tanner, personal communication, December 21, 2021

G. Leon Curtis, personal communication, February 7, 2009.

Ilene Coles Kinner, Personal Interview, December 26, 2010.

Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, December 26, 2010

Michelle Tanner, personal communication, December 21, 2021

References

“Arvel Christensen Retires From Barbering.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 8, no. 4 (November 1973): 4.

Banks, Gladys W. & Banks, Douglas W. "The DeLong Family Saga.

Burdett, Kenneth, C. “Lee Shepherd.” The Utah Eagle, vol. 58, no. 4 (January 1947): 9.

“Death.” The Silent Worker, vol. 37, no. 7 (April 1925): 359.

Driggs, Frank, M. The Utah Eagle, vol. XIII, no. 2 (November 1, 1901): 16.

Evans, David S. “A Silent World in the Intermountain West: Records from the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind: 1884-1941.” A thesis presented to the Department of History: Utah State University. 1999.

“Exchange.” The Silent Worker, vol. 29, no. 2 (November 1916): 33.

“Harry Sanger Smith.” The Silent Worker, vol. 13, no. 1 (September 1990): 5.

“It is great, our School for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind.” The Utah Eagle, vol. IX, no.1 (September 15, 1897): 1-2.

"Keen Action By OSC Workers Reveals Fraud." The IRS Newsletter. (1977).

“Miss C.V. Eddy.” The Silent Worker, vol. 10, no. 5 (January 1898): 73.

“New Developments in Utah’s Educational Programs for the Deaf.” The Utah Eagle, vol. 79, no. 5 (February 1968): 13 – 15.

“News of Note.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 7, no. 10 (March 1984): 5.

“Obituary.” The Silent Worker, vol. 37, no, 7 (April 1925): 359.

“Printer Serves 50 Years Engineer Closes Career.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 7 (Summer 1962): 3.

Roberts, Elaine M. “The early history of the Utah School for the Deaf and its influence in the development of a cohesive Deaf society in Utah, circa. 1884 – 1905.” A thesis presented to the Department of History:Brigham Young University. August 1994.

“Starting Things.” The Silent Worker, vol. 36, no. 8, (May 1924): 365.

"Tax Examiner Uncovers Fraud." The Ogden Standard-Examiner. (March 19, 1977): 9.

“Tribute to Harry S. Smith.” The Silent Worker, vol. 38, no. 8 (May 1925): 385.

“The Utah School for the Deaf.” The Silent Worker, vol. 9, no. 5 (January 1897): 77.

"Utah Deaf People in Business and Industry ...in the Space Age." The UAD Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 3 (Summer 1968).

Utah School for the Deaf Program Book, 1960s.

“With Our Exchanges.” The Silent Worker, vol. 18, no. 9 (June 1906): 141.

White, Bob. “Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32 no. 7 (April 1920): 186.

White, Bob. “Notes and Comment From the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32, no. 9 (June 1920): 243.

White, Bob. “Winding Trails.” The Silent Worker, vol. 33, no. 2 (November 1920): 59-60 & 62.

“WM. Cole, Carlos Seegmiller Honored.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 7 (Summer 1962): 3 & 10.

Banks, Gladys W. & Banks, Douglas W. "The DeLong Family Saga.

Burdett, Kenneth, C. “Lee Shepherd.” The Utah Eagle, vol. 58, no. 4 (January 1947): 9.

“Death.” The Silent Worker, vol. 37, no. 7 (April 1925): 359.

Driggs, Frank, M. The Utah Eagle, vol. XIII, no. 2 (November 1, 1901): 16.

Evans, David S. “A Silent World in the Intermountain West: Records from the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind: 1884-1941.” A thesis presented to the Department of History: Utah State University. 1999.

“Exchange.” The Silent Worker, vol. 29, no. 2 (November 1916): 33.

“Harry Sanger Smith.” The Silent Worker, vol. 13, no. 1 (September 1990): 5.

“It is great, our School for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind.” The Utah Eagle, vol. IX, no.1 (September 15, 1897): 1-2.

"Keen Action By OSC Workers Reveals Fraud." The IRS Newsletter. (1977).

“Miss C.V. Eddy.” The Silent Worker, vol. 10, no. 5 (January 1898): 73.

“New Developments in Utah’s Educational Programs for the Deaf.” The Utah Eagle, vol. 79, no. 5 (February 1968): 13 – 15.

“News of Note.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 7, no. 10 (March 1984): 5.

“Obituary.” The Silent Worker, vol. 37, no, 7 (April 1925): 359.

“Printer Serves 50 Years Engineer Closes Career.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 7 (Summer 1962): 3.

Roberts, Elaine M. “The early history of the Utah School for the Deaf and its influence in the development of a cohesive Deaf society in Utah, circa. 1884 – 1905.” A thesis presented to the Department of History:Brigham Young University. August 1994.

“Starting Things.” The Silent Worker, vol. 36, no. 8, (May 1924): 365.

"Tax Examiner Uncovers Fraud." The Ogden Standard-Examiner. (March 19, 1977): 9.

“Tribute to Harry S. Smith.” The Silent Worker, vol. 38, no. 8 (May 1925): 385.

“The Utah School for the Deaf.” The Silent Worker, vol. 9, no. 5 (January 1897): 77.

"Utah Deaf People in Business and Industry ...in the Space Age." The UAD Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 3 (Summer 1968).

Utah School for the Deaf Program Book, 1960s.

“With Our Exchanges.” The Silent Worker, vol. 18, no. 9 (June 1906): 141.

White, Bob. “Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32 no. 7 (April 1920): 186.

White, Bob. “Notes and Comment From the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32, no. 9 (June 1920): 243.

White, Bob. “Winding Trails.” The Silent Worker, vol. 33, no. 2 (November 1920): 59-60 & 62.

“WM. Cole, Carlos Seegmiller Honored.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 7 (Summer 1962): 3 & 10.