History of the Robert G. Sanderson

Community Center of the

Deaf & Hard of Hearing

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

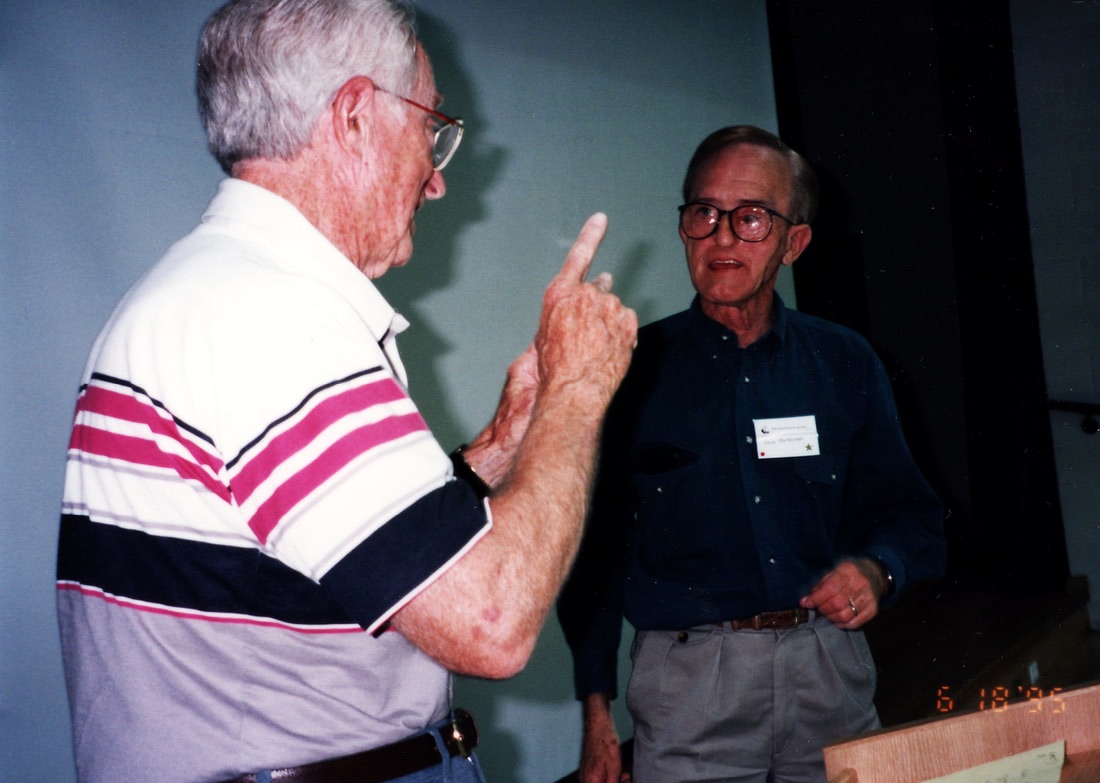

Author’s Note

I've had the pleasure of documenting the history of our Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, which is a treasured community hub for the Utah Deaf community. My family and I are regulars at the community center, and we consider it our second home. The center has been the source of countless cherished memories, and its absence would leave a void in our lives. I am deeply grateful to the leaders such as Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, W. David Mortensen, and others, who, as part of the Utah Association for the Deaf, dedicated 40 years from 1962 to 1992 to establish this community center through legislation. Their unwavering commitment has transformed our lives and significantly enhanced our quality of life through the activities, services, and training they have provided.

This webpage is not intended to duplicate Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's "A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing" book. This history aims to fill in the gaps, including the Utah Deaf community's battles with state authorities' decision-making process regarding the community center for the deaf, Dr. Grant B. Bitter's objections to the services provided by the community center for the deaf, and W. David Mortensen's strong advocacy for the community center. This post aims to help readers better understand how Deaf leaders overcome obstacles to establish the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading our 'History of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

This webpage is not intended to duplicate Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's "A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing" book. This history aims to fill in the gaps, including the Utah Deaf community's battles with state authorities' decision-making process regarding the community center for the deaf, Dr. Grant B. Bitter's objections to the services provided by the community center for the deaf, and W. David Mortensen's strong advocacy for the community center. This post aims to help readers better understand how Deaf leaders overcome obstacles to establish the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading our 'History of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Eleanor McCowan for making me work on the Utah Deaf History project, which I gladly accepted. None of this would have happened if it hadn't been for her request.

We incorporated further information from Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's "A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing" book. Thank you, Dr. Sanderson, for making my job a lot easier.

Eugene W. Petersen deserves credit for writing and publishing articles about establishing services for Deaf adults and supporting its mission.

Thanks to Marilyn T. Call for taking the time to review this material.

I sincerely appreciate W. David Mortensen's enthusiastic support while working on this project.

Valerie G. Kinney's invaluable assistance in editing and providing consultation direction while preparing this paper is recognized and gratefully appreciated.

Finally, I am indebted to my spouse, Duane Kinner, and my children, Joshua and Danielle, for their unwavering support and patience while I worked to complete this project.

We incorporated further information from Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's "A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing" book. Thank you, Dr. Sanderson, for making my job a lot easier.

Eugene W. Petersen deserves credit for writing and publishing articles about establishing services for Deaf adults and supporting its mission.

Thanks to Marilyn T. Call for taking the time to review this material.

I sincerely appreciate W. David Mortensen's enthusiastic support while working on this project.

Valerie G. Kinney's invaluable assistance in editing and providing consultation direction while preparing this paper is recognized and gratefully appreciated.

Finally, I am indebted to my spouse, Duane Kinner, and my children, Joshua and Danielle, for their unwavering support and patience while I worked to complete this project.

A Gathering Place of their Own

The history of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing traces back to 1946, when Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, also known as 'Sandie' and 'Bob' to his friends, proposed the idea of a gathering place for the Utah Deaf community. In his book 'A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing,' Dr. Sanderson details how the Utah Association of the Deaf first discussed the idea of a Deaf meeting place at the 1946 convention. At that time, Dr. Sanderson, who lived in Nevada, attended a convention where he observed Deaf individuals debating the establishment of their own 'Club for the Deaf' to set their own rules and meet at their convenience. The Utah Deaf community, noting the presence of deaf clubs in most major cities, questioned why such a club did not exist in Utah, particularly in Salt Lake City and Ogden. The book's author, Sandie, was unconcerned with their ideas because he was living in Nevada at the time (Sanderson, 2004, p. 1-2). Nonetheless, his book sheds light on these early discussions and the eventual realization of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

Sandie also mentioned that the Deaf community in Utah had been coming together for years for socials, parties, sporting events, and other activities. People often ask, "Why do we always beg for time and space?" They had to make do with whatever time, date, and place were available, not necessarily the ones they preferred. They would book various locations, such as a hotel ballroom, a local auditorium, the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind gymnasium, and the Murray B. Allen Center for the Blind. Strict rules were imposed, such as "in by seven, leave by nine" and having to pay the janitor extra if they stayed later. While the Utah Deaf community would have preferred their own gathering place, they were grateful for the cooperation of the Blind individuals and their leaders in using their facility (Sanderson, 2004, 1-2).

Sandie also mentioned that the Deaf community in Utah had been coming together for years for socials, parties, sporting events, and other activities. People often ask, "Why do we always beg for time and space?" They had to make do with whatever time, date, and place were available, not necessarily the ones they preferred. They would book various locations, such as a hotel ballroom, a local auditorium, the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind gymnasium, and the Murray B. Allen Center for the Blind. Strict rules were imposed, such as "in by seven, leave by nine" and having to pay the janitor extra if they stayed later. While the Utah Deaf community would have preferred their own gathering place, they were grateful for the cooperation of the Blind individuals and their leaders in using their facility (Sanderson, 2004, 1-2).

Possible Factors that Prevented Activism

In light of this, Dr. Sanderson proposed the theory that four potential factors prevented the Deaf community from accessing the "club for the Deaf."

Dr. Sanderson also recognized the potential of Deaf people to lead in various Deaf organizations, including the Utah Association of the Deaf, local divisions of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf, and others. However, he noted that they could benefit from more specific training to enhance their leadership skills, overcome their fears, and effectively communicate with the leaders of the hearing power structure (Sanderson, 2004).

- The Deaf adult population was unable to maintain a financially independent facility.

- The dominant religion, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, actively discouraged the use of alcohol among the Deaf adult population. To support the club, activists in other states would sell alcohol.

- To make a living and maintain a family, many Deaf people had an "eight to five" production job, leaving them little time to interact with high-level professionals in education, community agencies, or the legislature. Many couldn't afford to lose their jobs to get into politics. Only a small percentage of Deaf professionals received compensation for their participation in non-work-related community activities.

- There was a lack of trained Deaf leaders who could communicate Deaf people's needs to the hearing majority with the authority and money to make things happen (Sanderson, 2004).

Dr. Sanderson also recognized the potential of Deaf people to lead in various Deaf organizations, including the Utah Association of the Deaf, local divisions of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf, and others. However, he noted that they could benefit from more specific training to enhance their leadership skills, overcome their fears, and effectively communicate with the leaders of the hearing power structure (Sanderson, 2004).

Trained Utah Deaf Leaders

Things were about to change when Utah Deaf leaders, including Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who moved to Utah from Nevada in 1947, observed two national Deaf leaders, Gallaudet College graduates Dr. Boyce R. Williams and Dr. Malcolm Norwood, being able to communicate with hearing leaders of the power structure. Dr. Sanderson, a respected advocate for the Deaf community, played a crucial role in facilitating this communication and ensuring that the concerns of the Deaf community were heard. As the Director of the Office of Deafness in the Vocational Rehabilitation Administration under the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Dr. Williams, a good friend of Robert Sanderson, reached the administration's highest levels with a convincing message. He also brought public attention to the concerns of Deaf and hard of hearing people, who had received little attention for years, whereas other people with disabilities in the United States received more attention. Dr. Norwood, Director of the Office of Deaf Captioned Films, went above and beyond to educate top-level officials in the Department of Education about the importance of captioned films for Deaf people (Sanderson, 2004).

Dr. Williams and Dr. Norwood, in their tireless efforts to meet the accessibility needs of the general Deaf population, particularly the Utah Deaf community, not only inspired but also empowered Utah Deaf leaders. They encouraged these leaders to expand their legislative leadership and communication skills, enabling them to better serve the needs of the Deaf adult population. This is a significant part of the history of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, where Dr. Williams and Dr. Norwood served as beacons of inspiration for Utah Deaf leaders. They conducted workshops on various aspects of deaf issues at the local, regional, and national levels. Many Utah residents seized the opportunity to learn more about themselves and their personal needs (Sanderson, 2004).

Dr. Williams and Dr. Norwood, in their tireless efforts to meet the accessibility needs of the general Deaf population, particularly the Utah Deaf community, not only inspired but also empowered Utah Deaf leaders. They encouraged these leaders to expand their legislative leadership and communication skills, enabling them to better serve the needs of the Deaf adult population. This is a significant part of the history of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, where Dr. Williams and Dr. Norwood served as beacons of inspiration for Utah Deaf leaders. They conducted workshops on various aspects of deaf issues at the local, regional, and national levels. Many Utah residents seized the opportunity to learn more about themselves and their personal needs (Sanderson, 2004).

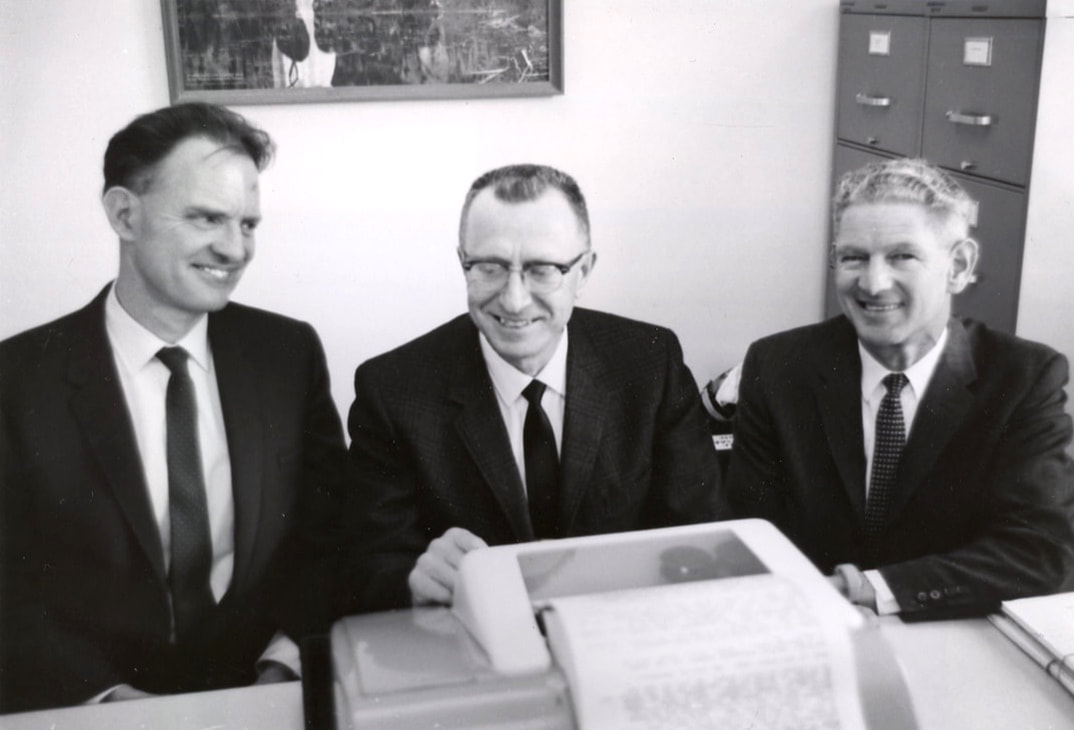

Boyce R. Williams (center) received the first Daniel T. Cloud Memorial Award for Leadership in a special ceremony in conjunction with commencement exercises at San Fernando Valley State College. Dr. Ray L. Jones, (left) Director of the Leadership Training Program in the Area of the Deaf which sponsors the award, made the presentation. Robert Sanderson (right) president of the National Association of the Deaf, was present for the ceremony. The Utah Eagle, November 1968

The National Leadership Training Program in the Area of the Deaf, which symbolized inclusivity, was established at San Fernando Valley State College (later renamed California State University at Northridge) in California in 1962. The program received funding from the Rehabilitation Services Administration and aimed to address the social, educational, and economic issues faced by Deaf individuals by providing comprehensive training and support. The college made history as the first in the United States to hire full-time sign language interpreters in a graduate program. Many Deaf and hard of hearing individuals applied to the program, with a balanced representation of five Deaf and ten hearing individuals. The selection process for the LTP Class of 1965 was rigorous, requiring applicants to demonstrate a strong commitment to the Deaf community and a clear vision for their future involvement. One of the Deaf applicants, Robert G. Sanderson from Utah, met these criteria and joined the program (The UAD Bulletin, Winter 1964; Sanderson, 2004).

Observation of the National Deaf Club

At that time, the Deaf community was trying to create a Deaf club. However, a lack of leadership experience and resources made progress difficult. They wanted to establish a Deaf club and service agency to help address the social, educational, and economic issues Deaf individuals face, similar to existing clubs in larger cities. This struggle highlighted the challenges that the Deaf community was dealing with.

Dr. Sanderson, during his tenure as president of the National Association of the Deaf, visited various clubs that catered to the social interaction needs of Deaf individuals. These clubs offered activities such as cards, captioned movies, sports, chatting, and parties, serving as crucial social and recreational outlets for the Deaf community. The primary sources of revenue for these clubs were liquor and food sales, and some had purchased their own run-down structures. Dr. Sanderson noted that many club members expressed concerns about lacking employment opportunities, mental health services, and other essential needs. He observed that the club leaders lacked the necessary training to address the needs of the Deaf individuals they served directly. Additionally, Dr. Sanderson highlighted the absence of comprehensive Deaf centers in newsletters and publications across the country.

On a more positive note, professional publications actively advocated for the need for psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers who were fluent in sign language and could effectively communicate with Deaf people. Dr. Sanderson partnered with Dr. Boyce Williams through the Rehabilitation Services Administration to organize and fund a series of workshops addressing these pressing issues. The ultimate goal was to establish a nationwide deaf rehabilitation program in each state, a significant step towards a more inclusive future for the Deaf community.

Dr. Sanderson, during his tenure as president of the National Association of the Deaf, visited various clubs that catered to the social interaction needs of Deaf individuals. These clubs offered activities such as cards, captioned movies, sports, chatting, and parties, serving as crucial social and recreational outlets for the Deaf community. The primary sources of revenue for these clubs were liquor and food sales, and some had purchased their own run-down structures. Dr. Sanderson noted that many club members expressed concerns about lacking employment opportunities, mental health services, and other essential needs. He observed that the club leaders lacked the necessary training to address the needs of the Deaf individuals they served directly. Additionally, Dr. Sanderson highlighted the absence of comprehensive Deaf centers in newsletters and publications across the country.

On a more positive note, professional publications actively advocated for the need for psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers who were fluent in sign language and could effectively communicate with Deaf people. Dr. Sanderson partnered with Dr. Boyce Williams through the Rehabilitation Services Administration to organize and fund a series of workshops addressing these pressing issues. The ultimate goal was to establish a nationwide deaf rehabilitation program in each state, a significant step towards a more inclusive future for the Deaf community.

Utah Association of the Deaf

Officers Becomes Activists

Officers Becomes Activists

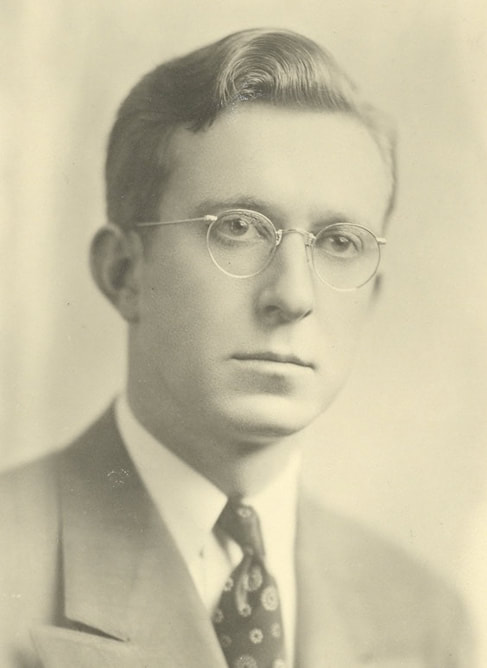

During a period of national change, the Deaf Utahns, in a display of proactive initiative, launched a lobbying effort to secure rehabilitative programs for themselves. This group of advocates, which included Robert G. Sanderson, Eugene W. Petersen, and G. Leon Curtis, officers of the Utah Association of the Deaf, were not content to wait for change; they were determined to make it happen (Sanderson, 2004).

The three Utah Association of the Deaf officials, Sandie, Eugene, and Leon, demonstrated exceptional leadership and commitment in spearheading the planning process. Their efforts, which began in 1962, aimed to establish a full-time office to serve the Deaf people of Utah. Their primary concern was Deaf adults' inability to access necessary services, and their goal was to ensure Utah's state provided more adequate and accessible social services. The communication barriers made it practically impossible for Deaf adults to receive the services they needed (The UAD Bulletin, Winter 1965).

The three Utah Association of the Deaf officials, Sandie, Eugene, and Leon, demonstrated exceptional leadership and commitment in spearheading the planning process. Their efforts, which began in 1962, aimed to establish a full-time office to serve the Deaf people of Utah. Their primary concern was Deaf adults' inability to access necessary services, and their goal was to ensure Utah's state provided more adequate and accessible social services. The communication barriers made it practically impossible for Deaf adults to receive the services they needed (The UAD Bulletin, Winter 1965).

In Utah, Deaf leaders requested that the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation develop services for Deaf adults. They proposed that personnel should split their time between vocational rehabilitation and social services, focused on the accessibility needs of the Deaf community. Their vision for social services included counseling, interpreting, and support in legal, personal, social, emotional, marriage and family, financial, and educational matters. They emphasized the importance of having qualified personnel proficient in sign language and understanding Deaf culture, who could effectively communicate with and assist Deaf adults in addressing issues and deprivations faced by the Utah Deaf community, such as language deprivations and education and employment issues. Furthermore, the leaders stressed that the proposed agency would only intervene in personal problems if requested and if the issues were beyond individuals' ability to handle independently. They clarified that they did not intend to replace, duplicate, or interfere with the activities of existing Utah Deaf community organizations (The UAD Bulletin, Winter 1965).

The Utah Association of the Deaf initiated a campaign to comprehensively research the issues faced by Deaf adults in the social service system. They emphasized the importance of documenting the need for services for Deaf adults and conducting a thorough examination to efficiently and cost-effectively provide these services. Sandie, Eugene, and Leon quickly developed a strategy to seek assistance from the Salt Lake Area United Fund in establishing social services for the Deaf. Meanwhile, Sandie was preparing to leave Utah for the National Leadership Training Program in the Deaf Area of California, and he entrusted Eugene and Leon with getting the ball rolling (Sanderson, 2004).

Did You Know?

By 1963, most Deaf adults who were born deaf had used hearing aids, learned to read lips, and learned how to speak before acquiring the language. The obstacle they faced was the 'mental starvation' resulting from language deprivation. They also struggled with their speech and language. They sought services to help them live effectively with their hearing loss. However, they rarely responded to those kinds of vocational rehabilitation services. Instead, they needed more help transitioning into life, like personal adjustment services, vocational training, counseling, and job placement. It's crucial to understand that deaf adults were not interested in hearing and speech services. This distinction is often misunderstood, with many professionals and laypeople mistakenly including the oral Deaf people with the millions of hard of hearing people. Those who were hard of hearing mainly communicated 'through their ears.' Those who gradually lost their hearing were not a clear group. With the assistance of hearing aids, they had to learn to talk and understand the language. The most common treatments they looked for were hearing aids, lip reading, speech correction, and training to improve their hearing (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963, p. 3).

A Study Committee Under the

Community Services Council Forms

Community Services Council Forms

The Utah Association for the Deaf requested admission to the Salt Lake Area United Fund as a participating member to highlight the lack of accessible services that affect Deaf adults. The United Fund staff were very interested in the issues brought up by the Deaf leaders. The Fund's admissions committee discussed and favored pursuing more research into the problems, including the association's request to record the number of Deaf adults needing services and thoroughly assess the most cost-effective and efficient ways to meet their needs. As a result, the committee developed the study and made recommendations. The United Fund's admissions committee referred the study task to the Community Services Council, the fund's organizer, for further investigation. In March 1963, the Community Services Council agreed to propose a project, which they presented in December of the same year. A study committee under the Community Services Council also accepted the task of looking into all community agencies and seeing if they could provide the needed services for Deaf adults in the state of Utah (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963; The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963).

Furthermore, the Community Services Council, in a display of collective commitment, coordinated 87 public and volunteer organizations to address the health, welfare, and recreation needs of Utah's half-million people. The chair of the Study Committee, Dr. Lawrence D. Schroder, delivered the study's conclusion, which included recommendations for establishing a service within an existing public or volunteer program to meet the needs of Deaf people. This conclusion was the result of several organizations working together to make the new services more accessible to Deaf adults (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963).

Darell J. Vorwaller, an assistant executive of the Community Services Council, formed a Study Committee consisting of fourteen Deaf and hearing individuals to investigate the challenges faced by Deaf adults and explore potential integration into an existing organization that represents a diverse range of community interests. The committee selected Larry W. Blake, personnel manager for Ajax Pressing Machine Co., one of the area's largest employers of Deaf workers, as its chairman. Members of the committee included G. Harold Bradley, Adult Evening School; Philip R. Clinger, Division of Vocational Rehabilitation; Marguerite Davis, Salt Lake County Department of Public Welfare; Clarence O. Fingerle, Salt Lake Country General Hospital; Vera Gee, Utah State Department of Health; Madeleine Helfrey, Department of Special Education, University of Utah; C. Russell Neale, Community Mental Health Center; R. Elwood Pace, State Department of Public Instruction; Ray G. Wenger (Hard of Hearing), Governor's Advisory Council of the Utah School for the Deaf; Brigham E. Roberts, Harvey S. Eugene W. Petersen (Deaf), and Jerry Westberg (Deaf) represented the Utah Association for the Deaf. Eula Pusey served as an interpreter (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963; Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963; The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1964; Sanderson, 2004).

Furthermore, the Community Services Council, in a display of collective commitment, coordinated 87 public and volunteer organizations to address the health, welfare, and recreation needs of Utah's half-million people. The chair of the Study Committee, Dr. Lawrence D. Schroder, delivered the study's conclusion, which included recommendations for establishing a service within an existing public or volunteer program to meet the needs of Deaf people. This conclusion was the result of several organizations working together to make the new services more accessible to Deaf adults (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963).

Darell J. Vorwaller, an assistant executive of the Community Services Council, formed a Study Committee consisting of fourteen Deaf and hearing individuals to investigate the challenges faced by Deaf adults and explore potential integration into an existing organization that represents a diverse range of community interests. The committee selected Larry W. Blake, personnel manager for Ajax Pressing Machine Co., one of the area's largest employers of Deaf workers, as its chairman. Members of the committee included G. Harold Bradley, Adult Evening School; Philip R. Clinger, Division of Vocational Rehabilitation; Marguerite Davis, Salt Lake County Department of Public Welfare; Clarence O. Fingerle, Salt Lake Country General Hospital; Vera Gee, Utah State Department of Health; Madeleine Helfrey, Department of Special Education, University of Utah; C. Russell Neale, Community Mental Health Center; R. Elwood Pace, State Department of Public Instruction; Ray G. Wenger (Hard of Hearing), Governor's Advisory Council of the Utah School for the Deaf; Brigham E. Roberts, Harvey S. Eugene W. Petersen (Deaf), and Jerry Westberg (Deaf) represented the Utah Association for the Deaf. Eula Pusey served as an interpreter (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963; Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963; The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1964; Sanderson, 2004).

During the year of 1963, the Study Committee met on a weekly basis. They spent a significant amount of time studying the challenges Deaf adults faced. The publication of a detailed 22-page report on "Services to Adult Deaf, Salt Lake Area" was a significant step toward realizing efforts to provide services, which were a recognized aspect of life in a metropolis, particularly for Deaf adults in the Salt Lake area (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963). The committee report gained widespread attention, and around 100 copies were requested for a national workshop for social workers held in Berkeley, California, on November 18–22, 1963 (Sanderson, 2004).

Study Results in Recommendations

for Community Services

in the Salt Lake Area for Deaf Adults

for Community Services

in the Salt Lake Area for Deaf Adults

Eugene W. Petersen, a member of the Study Committee and a board member of the Utah Association for the Deaf, advocated for deaf social services. Eugene highlighted the main reason the Utah Association for the Deaf sought assistance in the December 1963 issue of The Silent Worker: the inaccessibility of services for Deaf adults. The goal was to ensure that community services were accessible and free of communication barriers for Deaf adults. The committee collected data from Deaf adults and health and welfare agencies to identify the needs of the approximately 300 Deaf adults in the area. The findings revealed that Deaf adults faced significant challenges in accessing community services due to communication barriers, despite expressing a significant need for them.

It was evident that the majority of services for Deaf adults were only available to children or at speech and hearing centers. This inequality in services provided to Deaf adults and children was unjust. The focus on speech and hearing services, which were not very beneficial for Deaf adults, exacerbated the issue. The counseling service was deemed ineffective due to a lack of convenient and accessible communication (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963).

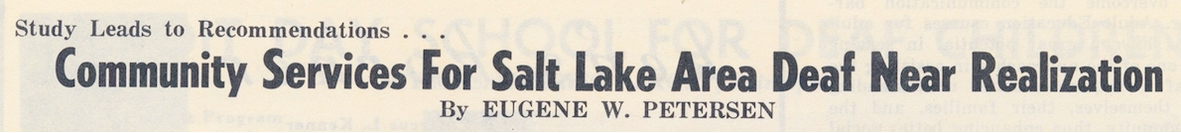

Eugene W. Petersen's article in The Silent Worker from December 1963, as quoted in the section below, provides a comprehensive summary of the committee's findings, conclusions, and recommendations. It's important to note that language and vocabulary used to be different in the 1960s, and "Adult Deaf" was the term used by Utah Deaf leaders to refer to deaf adults. Keep in mind that language and vocabulary were different in the 1960s, and "Adult Deaf" was the term used by Utah Deaf leaders to refer to Deaf adults today.

It was evident that the majority of services for Deaf adults were only available to children or at speech and hearing centers. This inequality in services provided to Deaf adults and children was unjust. The focus on speech and hearing services, which were not very beneficial for Deaf adults, exacerbated the issue. The counseling service was deemed ineffective due to a lack of convenient and accessible communication (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963).

Eugene W. Petersen's article in The Silent Worker from December 1963, as quoted in the section below, provides a comprehensive summary of the committee's findings, conclusions, and recommendations. It's important to note that language and vocabulary used to be different in the 1960s, and "Adult Deaf" was the term used by Utah Deaf leaders to refer to deaf adults. Keep in mind that language and vocabulary were different in the 1960s, and "Adult Deaf" was the term used by Utah Deaf leaders to refer to Deaf adults today.

Eugene W. Petersen's

Summary of Findings and Conclusions

for Deaf Adult Services

Summary of Findings and Conclusions

for Deaf Adult Services

- "Adult deaf persons represent a group for whom community services, although available, cannot be readily rendered. The barrier obstructing the provision of such services on an equitable basis with that of the hearing population is the inability of the persons requesting the services to communicate with those who offer the services. This is particularly true of casework and psychological or psychiatric services, which are dependent upon the flow of free and spontaneous communication between client and worker or therapist. Because of the communication barrier afflicting the deaf handicapped person, he is more prone to the development of social and emotional problems than are hearing persons, and this difficulty is intensified by the inability of professional persons to render needed services. Although the number of persons who would use these services in Salt Lake County in any one year cannot be documented, it would be a sizable proportion of the 296 estimated adult deaf persons residing in the county.

- In the process of seeking professional help with social and emotional problems, deaf persons realize little success in finding the desired services, either from community health and welfare agencies or from speech and hearing services as presently constituted. In a survey of deaf persons, it was disclosed that while over half of the persons represented in the survey are concerned with personal, social and emotional problems for which they desire professional help, one-third actually seek professional services, and only one-fifth receive a limited degree of satisfaction in the services rendered. Speech and hearing services are designed primarily to meet the needs of hard of hearing children and adults and deaf children, and fall short of meeting the need for social and emotional adjustment services for the adult deaf.

- Of the nine agencies and departments designated as carrying some responsibility for serving the deaf and hard of hearing, none, with the exception of the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, reported the provision of social and emotional adjustment services. The Division of Vocational Rehabilitation services are oriented to the gainful employment of those persons accepted as clients, and therefore, cannot serve deaf persons unless there is an indicated feasibility of gainful employment resulting from services rendered. Six of these nine agencies and departments limit their services to children.

- Other problems revealed by the survey to be of primary concern to the adult deaf, were management of finances and legal matters. These were followed by employment difficulties and health problems, with emotional problems often complicating the picture. Again, the basic problem is that of com-munication. The agencies reporting indicated that the accessibility of services to the adult deaf was conditional upon the extent to which communication did not significantly interfere with the rendering of services effectively. Nearly all of the 27 agencies indicated that services are available on this basis. Ten agencies not identical with those referred to in the preceding paragraph, indicated that contacts had been made by adult deaf in search of services.

- The Salt Lake County Department of Public Welfare rendered the largest number of services to adult deaf in 1962, the majority of whom had become deaf in later years. The Division of Vocational Rehabilitation served the next largest number of adult deaf. The other agencies reporting served from one to five persons on an irregular basis.

- Adult deaf persons were nearly unanimous regarding the felt need for Adult Education courses, provided that appropriate arrangements could be made to overcome the communication barrier. Adult Education courses for adult deaf have a great potential in serving as one of the approaches in assisting the deaf to acquire a better understanding of themselves, their families, and the community, thus enhancing better social and emotional adjustment" (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963, p. 3-4).

Eugene W. Petersen's

Summary of Recommendations

for Deaf Adult Services

Summary of Recommendations

for Deaf Adult Services

It is recommended:

- "That a service be established as a part of an existing public or voluntary agency in the Salt Lake area to render personal, social and emotional adjustment services to the adult deaf. The Family Service Society, Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, and the University of Utah Rehabilitation Center were considered as agencies which might logically provide such services. To meet manifest needs, the service should be designed to provide counseling or casework services in matters related to family, child behavior, personal, marital, budgeting, legal, employment relations and related problems, with provision for referral to sources of other services, when needed. An advisory committee, consisting of deaf and hearing persons, should be appointed by the agency in which the service is lodged, in order to assist in giving direction to the program.

- That a person be emploved by the designated agency who would be capable of communicating manually and orally with the deaf. Immediate needs suggest that the services of a skilled interpreter be employed in this position on a temporary basis until the ultimate objective of a professional social worker, skilled in communication with the deaf, can be achieved.

- That the broad obiective of the service be that of bringing about in the community an adequate social and emotional adjustment of the deaf, to enhance an integration of persons with this handicap into the total community.

- That services be clearly identified as a service for the deaf, for the purpose of enabling the development of public understanding of the service and of problems of the deaf.

- That the Graduate School of Social Work of the University of Utah be encouraged to recruit a student skilled in communication with the deaf by virtue of his background, such as the child of deaf parents, and that an appropriate stipend be awarded to underwrite the cost of training.

- That the State Division of Adult Education cooperate with the Utah Association for the Deaf in developing, on an experimental basis, classes for adult deaf, including such subjects as English, money management, mathematics, arts and crafts, vocational training, business and commercial courses, etc.

- That all health, welfare, and leisure time service agencies make effort to make appropriate services more accessible to the deaf. To this end, agencies should become better acquainted with the problems of deafness and develop special provisions needed in order to make services available to the deaf" (Petersen, The Silent Worker, December 1963, p. 3-4).

The Community Services Council

Highlights the Challenges Faced by Deaf Adults

Highlights the Challenges Faced by Deaf Adults

The Community Services Council in Utah highlighted several significant concerns regarding support for Deaf adults, which are as follows:

According to twenty-seven agencies, a report acknowledged that while the Deaf population has access to a wide range of services, communication barriers significantly hampered the quality and variety of these services (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963).

The Utah Association for the Deaf noted that the main challenge of being deaf is not the inability to hear or speak, but the lack of language. Every aspect of deaf education focuses on developing a functional vocabulary. Learning to speak and read lips takes time, and regardless of the educational methods employed, Deaf children lag behind their hearing peers by three to four years. The absence of auditory access to language in various aspects of life exacerbates this language deprivation into adulthood, as described by the Utah Association for the Deaf. Consequently, language deprivation significantly impacts the average Deaf adult, affecting their ability to comprehend social, economic, political, cultural, and humanitarian aspects of modern society (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963).

- Communicating with family, friends, and professionals can be difficult for a Deaf individual.

- A Deaf individual has difficulty understanding information about arrangements and plans of action.

- It is challenging to train a Deaf person due to communication barriers.

- Counseling services are entirely verbal understandings. The success of which is dependent on freedom of communication. This presents challenges while working with Deaf people.

- The lack of accessible communication is a concern. In recent years, several Deaf consumers known to agencies have not been in therapy for long. This could be due to a lack of experience dealing with Deaf adults or to the Deaf person's inability to be introspective or to participate in a casework relationship.

- The communication barrier limits Deaf people's ability to engage in social activities.

- Training people who are deaf in lipreading is difficult.

- It is challenging to obtain family health information in the cases found by public health nurses.

- Deaf parents struggle with teaching their hearing children to speak. Discipline issues emerge due to a breakdown in communication between the parent and the child.

- The communication barrier makes it difficult to give hearing evaluations.

- Deaf people lack knowledge of using community resources that provide health and social services. (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963, p. 4).

According to twenty-seven agencies, a report acknowledged that while the Deaf population has access to a wide range of services, communication barriers significantly hampered the quality and variety of these services (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963).

The Utah Association for the Deaf noted that the main challenge of being deaf is not the inability to hear or speak, but the lack of language. Every aspect of deaf education focuses on developing a functional vocabulary. Learning to speak and read lips takes time, and regardless of the educational methods employed, Deaf children lag behind their hearing peers by three to four years. The absence of auditory access to language in various aspects of life exacerbates this language deprivation into adulthood, as described by the Utah Association for the Deaf. Consequently, language deprivation significantly impacts the average Deaf adult, affecting their ability to comprehend social, economic, political, cultural, and humanitarian aspects of modern society (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963).

Larry W. Blake, left, received the first UAD Award from President G. Leon Curtis at the 21st Biennial Convention of the Utah Association for the Deaf. Miss Dixie Lee Nastfell served as the ceremony's interpreter. The award, a beautifully engraved silver tray, was awarded to Larry W. Blake in appreciation for his efforts on behalf of the Utah Deaf community. UAD Bulletin, Fall 1965

The study, completed in 1965, determined that the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation was the most suitable organization to lead the implementation of adequate services for the deaf. This division, operating through local district offices, offers comprehensive statewide services and has a diverse team of specialized professionals with a proven track record in working with individuals with disabilities (The UAD Bulletin, Winter 1965).

After two months of consideration, the Community Services Council presented its findings to the Utah State Board of Education. Although necessary, the budget request would significantly expand services for deaf adults in Utah, addressing a pressing need in our community. The Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Administration, recognizing the urgency of the situation, enthusiastically supported the plan (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

After two months of consideration, the Community Services Council presented its findings to the Utah State Board of Education. Although necessary, the budget request would significantly expand services for deaf adults in Utah, addressing a pressing need in our community. The Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Administration, recognizing the urgency of the situation, enthusiastically supported the plan (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

Did You Know?

The 1963 listing of agency services for Deaf adults did not include the Utah Association for the Deaf because it was a membership organization, not an agency that provides professional services to specific consumers. The association also operated a public awareness campaign to raise awareness of hearing loss, and it served many of the social and recreational needs of Deaf people through its membership activities (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1963, 3).

Lobbying the 1965 Utah State Legislature

for Services to the Deaf Adults

for Services to the Deaf Adults

Recognizing the financial was not feasible for establishing an ideal 'deaf club,' some local Deaf leaders made a significant shift in their focus. They began working with the Utah legislature, aiming to secure funding to create deaf services under the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation. During the 1965 Utah State Legislature session, these leaders, including UAD President G. Leon Curtis, made personal sacrifices that were not to be overlooked. They took time off from work without pay, accompanying Curtis to the Utah State Capitol. Their aim was to meet with Governor Calvin L. Rampton and lobby the legislature for funding. Eugene W. Petersen, Joseph B. Burnett, Ned C. Wheeler, and interpreter Eula Pusey were among these dedicated advocates for the Utah Deaf community (Curtis, The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965; Sanderson, 2004).

Nonetheless, the Legislative Budget Committee received excessive budget requests, causing the state to be unable to fulfill all requests. The committee had to make some cuts, resulting in the unfortunate elimination of funding for deaf services (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

The Utah Association for the Deaf showed unwavering determination in their advocacy efforts. They tirelessly met with members of the State Legislature, including Representatives Della L. Loveridge (D-Salt Lake), Nathaniel D. Clark (D-Ogden), and Earl H. Whittaker (R-Circleville), who prepared and introduced a bill. Governor Rampton and several legislators and senators were present. Additionally, many Deaf individuals wrote letters to their local legislators, urging for the financing of services (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

Despite the bill not being voted on the Utah Association for the Deaf's strategic approach proved successful when the influential Joint Appropriations Committee reevaluated and approved the funding request for deaf services (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

The Utah Association for the Deaf showed unwavering determination in their advocacy efforts. They tirelessly met with members of the State Legislature, including Representatives Della L. Loveridge (D-Salt Lake), Nathaniel D. Clark (D-Ogden), and Earl H. Whittaker (R-Circleville), who prepared and introduced a bill. Governor Rampton and several legislators and senators were present. Additionally, many Deaf individuals wrote letters to their local legislators, urging for the financing of services (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

Despite the bill not being voted on the Utah Association for the Deaf's strategic approach proved successful when the influential Joint Appropriations Committee reevaluated and approved the funding request for deaf services (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

To follow through, the influential Joint Appropriations Committee allocated $10,000 to the Department of Public Instruction for "straight" social services for Deaf adults. This was a significant step forward, marking the government's acknowledgment of the need for specialized services for the Deaf community (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965; Sanderson, 2004). It was a significant amount of money at the time, and the federal government would match it with $26,713 to build a new office for the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1966).

Finally, the Utah Association for the Deaf successfully lobbied for improved Deaf adult services. The Utah Association for the Deaf collaborated with the Salt Lake Area United Fund, the Community Services Council, and the State Legislature to achieve this success. This collaboration was a testament to the broad support and recognition of the importance of deaf services. Along the way, UAD also gained friends in the hearing community, further strengthening their advocacy efforts.

In light of this, the Utah Association for the Deaf clarified that they did not want special consideration for the Utah Deaf community. They wanted equal consideration for equal contributions. This wasn't about asking for more, but about giving Deaf people the same opportunities and support as hearing people. Deaf individuals would have more disadvantages and need support in a complicated and competitive society (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

Finally, the Utah Association for the Deaf successfully lobbied for improved Deaf adult services. The Utah Association for the Deaf collaborated with the Salt Lake Area United Fund, the Community Services Council, and the State Legislature to achieve this success. This collaboration was a testament to the broad support and recognition of the importance of deaf services. Along the way, UAD also gained friends in the hearing community, further strengthening their advocacy efforts.

In light of this, the Utah Association for the Deaf clarified that they did not want special consideration for the Utah Deaf community. They wanted equal consideration for equal contributions. This wasn't about asking for more, but about giving Deaf people the same opportunities and support as hearing people. Deaf individuals would have more disadvantages and need support in a complicated and competitive society (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

Robert G. Sanderson Appoints

as the First State Coordinator of Services

to Deaf People in Utah and the United States

as the First State Coordinator of Services

to Deaf People in Utah and the United States

When funds became available on July 30, 1965, the Utah Merit System Council announced the creation of a new position in the Department of Public Instruction, named Coordinator, Adult Deaf Services. At the time, Dr. Vaughn Hall was the state administrator of the Division of Rehabilitation (Sanderson, 2004).

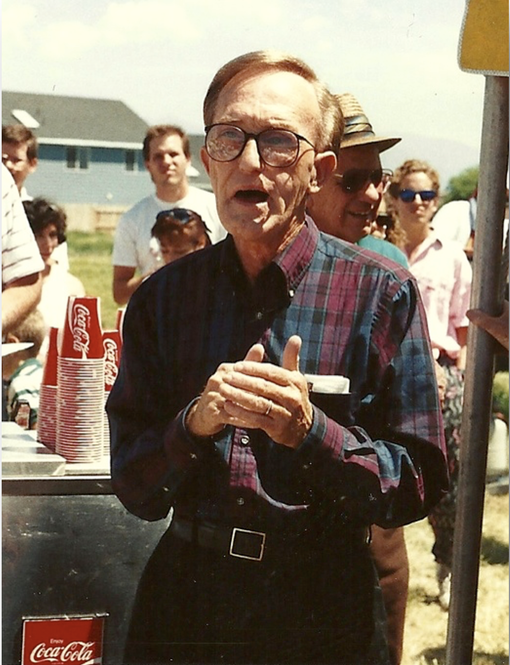

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who was still the president of the National Association of the Deaf and has recently completed his master's degree in educational administration in California, was an excellent choice for the newly created position of Coordinator of Adult Deaf Services. When the position opened up, Dr. Sanderson applied and was hired with strong support from the Utah Deaf community. Reflecting on his appointment, he said, 'I saw this as an opportunity to make a real difference in the lives of the Deaf community in Utah.' He became the first state coordinator of services to Deaf adults at the Atlas Building, 36 West Second South in Salt Lake City, Utah, on November 15, 1965 (Sanderson, 2004). In this position, he spearheaded advocacy efforts to establish a community center for the deaf and a specialized rehabilitation unit for the Deaf and hard of hearing, a testament to his commitment to the cause.

Social services for the deaf were established in the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation under the direction of Robert G. Sanderson. Dr. Boyce Williams, Dr. Mary Switzer, and others in Washington, DC, recognized the effectiveness of Utah's approach to rehabilitating Deaf individuals. As a result, other state rehabilitation departments quickly adopted Utah's methods as a model, demonstrating Utah's pioneering role in this field (Sanderson, 2004).

One-Year Anniversary of

Services to Deaf Adults

Services to Deaf Adults

In the fall of 1966, the Services for Deaf Adults marked their first anniversary. Dr. Sanderson and his team, including secretary Mildred Richardson, were overwhelmed by the work. Previously, the Utah Division of Vocational Rehabilitation handled approximately eleven deaf and hard of hearing people per year. When Dr. Sanderson started working, word spread that he spoke their language, and he soon had 94 clients. Many Deaf and hard of hearing people have been denied the assistance they need due to communication barriers. After Dr. Sanderson resolved the matter, he had a lot of work ahead of him (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1966). He served in two capacities: social services and rehabilitative services. His new job was demanding. He worked in rehabilitation, counseling, training, job placement, adult education, sign language workshops, and advocating for captioned films (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1966). The Services for Deaf Adults also provided support for families of Deaf and hard of hearing individuals, including counseling and educational resources.

Despite the numerous challenges and setbacks he encountered, Dr. Sanderson found his position to be the most rewarding of his career. In the Fall 1966 issue of the UAD Bulletin, he expressed his admiration for the Deaf and hard of hearing community, stating, "I enjoy working with these people. The vast majority are capable, self-reliant, and a credit to the community. Some of them need guidance and some additional training; others may need only a chance; they all need more understanding. The one thing they don't need or want is sympathy. The office is here to work with deaf adults and to help when needed. But it was not and never was intended to be done for them" (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1966).

Despite the numerous challenges and setbacks he encountered, Dr. Sanderson found his position to be the most rewarding of his career. In the Fall 1966 issue of the UAD Bulletin, he expressed his admiration for the Deaf and hard of hearing community, stating, "I enjoy working with these people. The vast majority are capable, self-reliant, and a credit to the community. Some of them need guidance and some additional training; others may need only a chance; they all need more understanding. The one thing they don't need or want is sympathy. The office is here to work with deaf adults and to help when needed. But it was not and never was intended to be done for them" (The UAD Bulletin, Fall 1966).

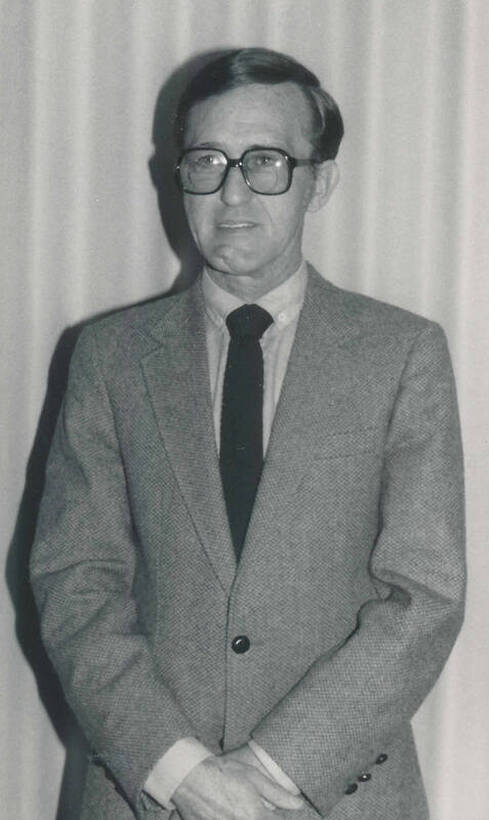

The Growth in Rehabilitation Service

Eugene W. Petersen, president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, noted the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services has been a beacon of hope for Deaf adults in Utah over the past two years, from 1965 to 1967. The number of new consumers receiving rehabilitation treatment has soared to 135, with 15 or 16 more eagerly awaiting their turn. This positive impact has not gone unnoticed, with the Utah State Legislature approving funding for a second counselor and an office assistant. The legislature also took a significant step by passing legislation to provide interpreters for Deaf people in court, relieving Dr. Sanderson of the burden of searching for an interpreter in court as a service coordinator (The UAD Bulletin, Spring-Summer 1967).

The Utah Association for the Deaf has been a welcoming home for the majority of Deaf consumers who were new to the community. These individuals, who had no exposure to sign language and little chance of becoming part of the Utah Deaf community, found a place where they were understood and their needs were met. They finally had the assistance they needed (The UAD Bulletin, Spring–Summer 1967). At the time, many of these Deaf people had multiple disabilities. The Utah School for the Deaf had over a third of its students with various disabilities (The UAD Bulletin, Spring–Summer 1967). Furthermore, the number of young Deaf adults seeking rehabilitative services has grown. Training, counseling, and placement proved challenging (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1966).

The Utah Association for the Deaf has been a welcoming home for the majority of Deaf consumers who were new to the community. These individuals, who had no exposure to sign language and little chance of becoming part of the Utah Deaf community, found a place where they were understood and their needs were met. They finally had the assistance they needed (The UAD Bulletin, Spring–Summer 1967). At the time, many of these Deaf people had multiple disabilities. The Utah School for the Deaf had over a third of its students with various disabilities (The UAD Bulletin, Spring–Summer 1967). Furthermore, the number of young Deaf adults seeking rehabilitative services has grown. Training, counseling, and placement proved challenging (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1966).

It was assumed that UAD would not be needed and that the state would care for Deaf individuals. However, this was a misconception. Dr. Sanderson argued that anyone who believes the "state will take care of us" is mistaken. It was expected to "give them all they desired" and "do more to help deaf people." The rehabilitation philosophy was to work with people rather than against them (The UAD Bulletin, Spring-Summer 1967). Dr. Sanderson also mentioned that people willing to work hard for themselves got the most out of their help. Learning a trade or attending school may take a long time and be challenging for Deaf people. Those unable to find fitting employment usually gave up or dropped out; those who successfully obtained employment in the selected trade stayed with the job and earned the necessary skills and abilities. He stressed that the services provided in the deaf rehabilitation program, such as vocational training and educational support, would not result in dependency. The goal was to enable Deaf people to develop independence and share community resources more equitably. For example, community-sponsored adult education programs tried to assist Deaf adults in overcoming educational limitations that turned them dependent. The rehabilitation program provided them with the skills they needed to become self-sufficient. Utah was not alone in this situation; other states faced similar challenges (The UAD Bulletin, Spring-Summer 1967).

Dr. Sanderson also emphasized the need for the National Association of the Deaf and the Utah Association for the Deaf to continue to work proactively to support those members of the Utah Deaf community who cannot always help themselves, particularly those with multiple disabilities. The number of individuals with various disabilities was on the rise, and it was crucial for volunteer organizations to continue to bring their special needs to the attention of government agencies. The Utah School for the Deaf recognized the challenges confronting these exceptional students and a collaboration was developed between USD and rehabilitation services to provide the necessary support (The UAD Bulletin, Spring-Summer, 1967).

Dr. Sanderson also emphasized the need for the National Association of the Deaf and the Utah Association for the Deaf to continue to work proactively to support those members of the Utah Deaf community who cannot always help themselves, particularly those with multiple disabilities. The number of individuals with various disabilities was on the rise, and it was crucial for volunteer organizations to continue to bring their special needs to the attention of government agencies. The Utah School for the Deaf recognized the challenges confronting these exceptional students and a collaboration was developed between USD and rehabilitation services to provide the necessary support (The UAD Bulletin, Spring-Summer, 1967).

Did You Know?

In 1965, the number of Deaf children with multiple disabilities was increasing. Whether educational authorities liked it or not, the day would come when these children would take over numerous residential schools. This may be true for Deaf children with multiple disabilities. It also means that Deaf children with average minds and skills were pushed into oral day schools, where their educational rights were often lost for the sake of integration (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

Beth Ann Stewart Campbell’s

New Role in the Deaf Section

New Role in the Deaf Section

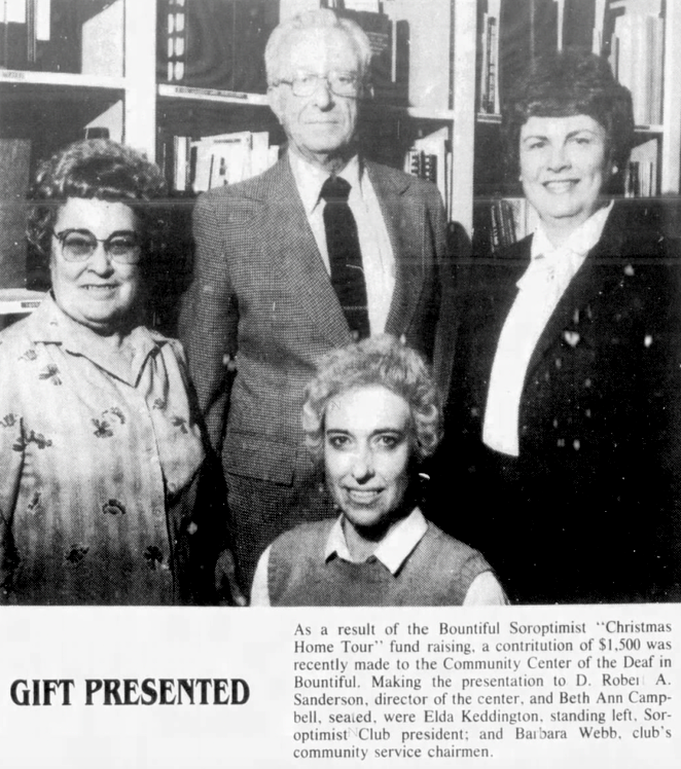

In 1967, Dr. Sanderson and his secretary, Linda Campbell, were the only two employees in the deaf unit (Stewart, DSDHH, April 2012). Three years later, in 1970, a significant addition was made to the team. Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a woman of remarkable contributions, joined the Division of Adult Education and Training as a rehabilitation assistant in the Services to the Deaf Section. She started working in 1969 after a resolution was passed at the convention by the Utah Association for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her employment was a result of a request for a female counselor to handle consumers who preferred to communicate with a woman (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1970–71).

Beth Ann, with her unwavering dedication, served as an assistant to Dr. Sanderson and Jack White, a son of Deaf parents Jack and Vida White and Provo Rehabilitation Counselor. Her responsibilities included consumer intake, interpretation, job placement, case reporting, follow-up, and work adjustment counseling (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1970-71).

Beth Ann, a well-known figure in the Utah Deaf community, was the daughter of Arnold and Zelma Moon, who were also deaf (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1970-71). Her interpreting responsibilities grew significantly throughout the years while she worked at the rehabilitation office (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, personal communication, September 20, 2012).

Beth Ann, a well-known figure in the Utah Deaf community, was the daughter of Arnold and Zelma Moon, who were also deaf (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1970-71). Her interpreting responsibilities grew significantly throughout the years while she worked at the rehabilitation office (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, personal communication, September 20, 2012).

Feasibility Study for a

Community Center for the Deaf

Community Center for the Deaf

Robert G. Sanderson, a dedicated and passionate individual, while employed at the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, envisioned a community center for the deaf. He spearheaded the effort to make this vision a reality, engaging in in-depth conversations for several years about what such a center should look like and what services it should provide.

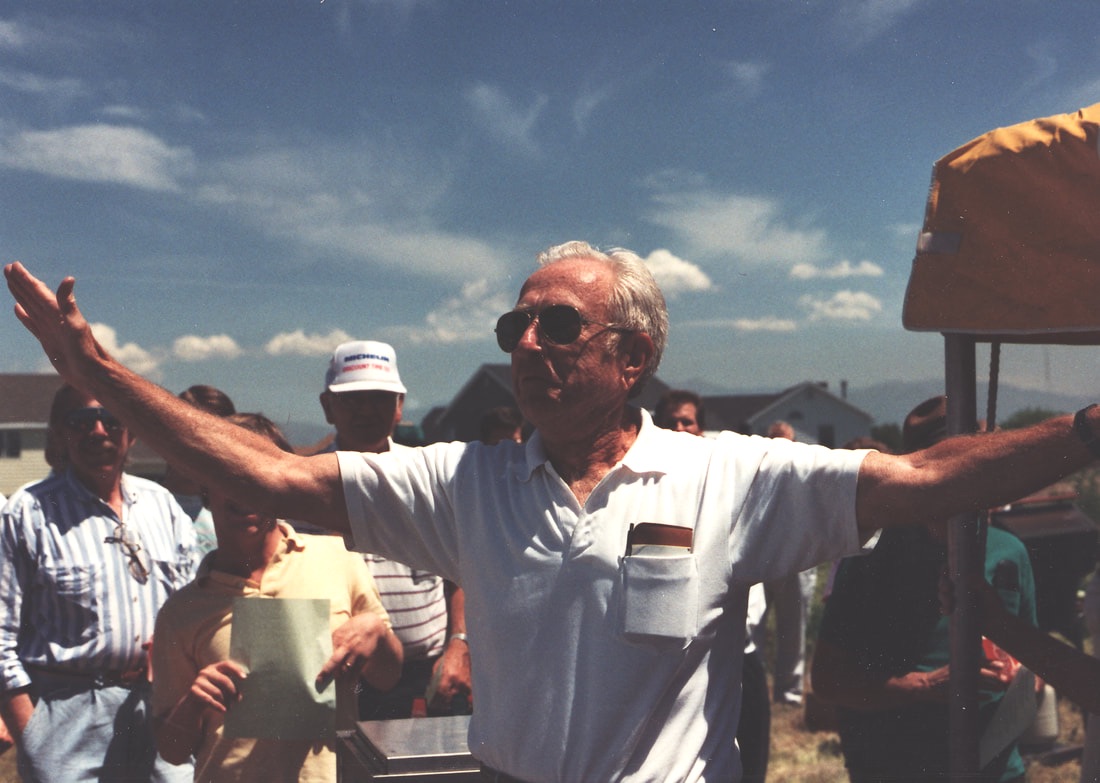

Dr. Sanderson's unwavering perseverance paid off in June 1975 when the initial notion of a community center emerged. Dr. Walter D. Talbot, Superintendent of Public Instruction for the Utah State Office of Education, established a committee to investigate the feasibility and desirability of creating a community center for the deaf in Utah, similar to the Murray B. Allen Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Dr. Sanderson, appointed as chairman, led the committee, which included Dr. Harvey Hirschi, Administrator, Division of Vocational Rehabilitation; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, Deputy Superintendent, Utah State Office of Education; Dr. Charles C. Schmitt, Facilities Coordinator, Division of Vocational Rehabilitation; and four Deaf members, W. David Mortensen, Lloyd H. Perkins, Dora B. Laramie, and Ned C. Wheeler (UAD Bulletin, December 1975; Sanderson, 2004).

Dr. Sanderson's unwavering perseverance paid off in June 1975 when the initial notion of a community center emerged. Dr. Walter D. Talbot, Superintendent of Public Instruction for the Utah State Office of Education, established a committee to investigate the feasibility and desirability of creating a community center for the deaf in Utah, similar to the Murray B. Allen Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Dr. Sanderson, appointed as chairman, led the committee, which included Dr. Harvey Hirschi, Administrator, Division of Vocational Rehabilitation; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, Deputy Superintendent, Utah State Office of Education; Dr. Charles C. Schmitt, Facilities Coordinator, Division of Vocational Rehabilitation; and four Deaf members, W. David Mortensen, Lloyd H. Perkins, Dora B. Laramie, and Ned C. Wheeler (UAD Bulletin, December 1975; Sanderson, 2004).

On December 1, 1975, Dr. Walter Talbot, the State Superintendent of Instruction, received a comprehensive 47-page feasibility report with recommendations (UAD Bulletin, December 1975). Governor Calvin L. Rampton and various national and local organizations, such as the National Association of the Deaf, the Utah Association for the Deaf, the Utah Athletic Club for the Deaf, and the Parent-Teacher-Student Association of the Utah School for the Deaf, expressed their endorsement for the community center, extending its support beyond the local level (Sanderson, 2004).

Deaf Members of the Feasibility Study

for a Community Center for the Deaf Committee

for a Community Center for the Deaf Committee

Dr. Talbot, along with Dr. Sanderson, and his interpreter, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, made multiple visits to the capital funding legislative committee during the legislative process. Governor Rampton's support for the process proved to be invaluable (Sanderson, 2004).

All of the legislative committees had finally approved a bill. At the end of the regular legislative session in February 1977, Governor Rampton had the bill on his desk at midnight. He was about to sign it when he noticed that the term "deaf" had been mistyped as "blind"! This seemingly small error had significant consequences. He couldn't fix it because the legislature had closed at midnight (Sanderson, 2004).

Dr. Sanderson was informed by the Legislative Research Staff that bills and resolutions that 'failed' or did not pass may not have been filed or archived. In other words, the bill did not successfully navigate the legislative process. No one had informed him of the status of such legislation, and he received no personal explanation as to how the mix-up occurred. He believed it was a Freudian slip on the part of some bill sponsor or legislator who was thinking about blind people because they were more visible than the deaf. In any case, Dr. Sanderson could not locate any evidence to support the story. The emotional toll on the Deaf leaders was immense when they learned that the bill had failed due to an erroneous oversight. They had dedicated weeks to testifying on behalf of the Utah Deaf Community Center in several parliamentary committees (Sanderson, 2004).

Last but not least, Dr. Sanderson pointed out the alarming absence of the Utah State Board of Education minutes from 1975, 1976, 1977, 1980, and 1981, which included studies, resolutions, and bills for the legislature. These crucial documents were nowhere to be found! Moreover, a center was not included in State Superintendent Talbot's 1976 budget. Perhaps the Deaf leaders overlooked anything because the yearly minutes' books were so thick! Nonetheless, the UAD Bulletin and Silent Spotlight have proven valuable tools for tracking the center's progress over time (Sanderson, 2004).

Dr. Sanderson was informed by the Legislative Research Staff that bills and resolutions that 'failed' or did not pass may not have been filed or archived. In other words, the bill did not successfully navigate the legislative process. No one had informed him of the status of such legislation, and he received no personal explanation as to how the mix-up occurred. He believed it was a Freudian slip on the part of some bill sponsor or legislator who was thinking about blind people because they were more visible than the deaf. In any case, Dr. Sanderson could not locate any evidence to support the story. The emotional toll on the Deaf leaders was immense when they learned that the bill had failed due to an erroneous oversight. They had dedicated weeks to testifying on behalf of the Utah Deaf Community Center in several parliamentary committees (Sanderson, 2004).

Last but not least, Dr. Sanderson pointed out the alarming absence of the Utah State Board of Education minutes from 1975, 1976, 1977, 1980, and 1981, which included studies, resolutions, and bills for the legislature. These crucial documents were nowhere to be found! Moreover, a center was not included in State Superintendent Talbot's 1976 budget. Perhaps the Deaf leaders overlooked anything because the yearly minutes' books were so thick! Nonetheless, the UAD Bulletin and Silent Spotlight have proven valuable tools for tracking the center's progress over time (Sanderson, 2004).

Utah State Board of Education

Adopts a Policy on Deaf

Adopts a Policy on Deaf

Following a lengthy debate, the Utah State Board of Education agreed on June 15, 1976, to establish a policy statement that resulted in the decentralization of counselors for Deaf vocational rehabilitation consumers. The new policy relocated counselors from the state school office to the vocational rehabilitation offices in Ogden, Salt Lake City, and Provo. Consumers at those offices might choose between 'total communication' and 'oralist' counselors. Dr. Vaughan Hall, the associate state superintendent, made the change in response to oralists' complaints about not having a clear choice in selecting their counselors. Additionally, numerous oralists testified that they hesitated to visit the state school's vocational rehabilitation office [Utah School for the Deaf] for fear of not receiving the desired services. Totalists, on the other hand, were opposed to the new policy and expressed fear that it would weaken the services provided to consumers seeking vocational rehabilitation. Dr. Vaughan, however, provided reassurance that the new approach would not reduce services; instead, he believed it would give consumers more options and allow counselors to adapt offerings of better services to meet their needs, instilling confidence in the new policy (The Salt Lake Tribune, June 16, 1976).

On June 16, 1976, W. David Mortensen, a respected figure in the Utah Deaf community and president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, issued an article discussing his thoughts on the Board of Education's recent decision. He stated the following:

On June 16, 1976, W. David Mortensen, a respected figure in the Utah Deaf community and president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, issued an article discussing his thoughts on the Board of Education's recent decision. He stated the following:

Won’t Listen

“The Board of Education is making a serious mistake in listening to the wrong people in its plan to “decentralize” services to deaf people. Never once did they invite the input of the deaf people of the community itself. They listened only to people who do not understand the implications of deafness. People who do not know nor understand what it means to live in deafness everyday. They listened to people into their ivorytowers who are far removed from the reality of life.

Never once did the Board of Education or personnel connected with it ask the deaf community nor make a survey of the services provided to the deaf to see if the present organization was satisfactory. The deaf community asked for services years ago and has been happy with the services rendered. Why change without asking the consumer if he likes what he’s getting?

The deaf people are tired of paternalism, of being told by hearing people and educators that all we need is more speech and lip reading. We express to them – that such concepts deny deafness – and mislead people who have deaf children who will one day be as we are – deaf adults!

Apparently, the Board of Education is turning its back on deaf people, upon the mass of experience, and is listening only to those who have axes to grind. It was the deaf community that forced the board to take a hard look at its educational programs at the deaf school; to take another look at the conditions in school dormitories and to evaluate them.

If it were not for the alertness of the deaf people then parents of deaf children would continue to receive a less than adequate program for their children. When deaf people speak, we speak with knowledge and experience, and perception that no hearing person can experience.

We believe the Board of Education should retain its Unit of Services to the Deaf as it is presently made up, and if needed, add another counselor to work exclusively with those deaf who are, by personal choice, oral in philosophy. We support the desires of such deaf people when they express themselves but no when others paternalistic step in and try to do for them” (Mortensen, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 16, 1976).

It was speculated that Dr. Grant B. Bitter, an active and vocal oral advocate and then professor of the University of Utah's Oral Training Program, as well as coordinator of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Deaf Seminary for the State of Utah, would be involved in the new changes.

Never once did the Board of Education or personnel connected with it ask the deaf community nor make a survey of the services provided to the deaf to see if the present organization was satisfactory. The deaf community asked for services years ago and has been happy with the services rendered. Why change without asking the consumer if he likes what he’s getting?

The deaf people are tired of paternalism, of being told by hearing people and educators that all we need is more speech and lip reading. We express to them – that such concepts deny deafness – and mislead people who have deaf children who will one day be as we are – deaf adults!

Apparently, the Board of Education is turning its back on deaf people, upon the mass of experience, and is listening only to those who have axes to grind. It was the deaf community that forced the board to take a hard look at its educational programs at the deaf school; to take another look at the conditions in school dormitories and to evaluate them.

If it were not for the alertness of the deaf people then parents of deaf children would continue to receive a less than adequate program for their children. When deaf people speak, we speak with knowledge and experience, and perception that no hearing person can experience.

We believe the Board of Education should retain its Unit of Services to the Deaf as it is presently made up, and if needed, add another counselor to work exclusively with those deaf who are, by personal choice, oral in philosophy. We support the desires of such deaf people when they express themselves but no when others paternalistic step in and try to do for them” (Mortensen, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 16, 1976).

It was speculated that Dr. Grant B. Bitter, an active and vocal oral advocate and then professor of the University of Utah's Oral Training Program, as well as coordinator of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Deaf Seminary for the State of Utah, would be involved in the new changes.

Restructure the Office

of Services to the Deaf

of Services to the Deaf

On June 15, 1978, the Utah State Board of Education decided to restructure the Office of Services to the Deaf. The Utah Association for the Deaf expressed concern and outrage over the impending implementation of the reorganization. Since the community had not received the latest policy statement or the new organizational chart, uncertainty loomed regarding the impact of this change on various Deaf services (The Silent Spotlight, June 1978).

Dr. Walter Talbot, the State Superintendent of Education, sought to reassure the Utah Deaf community by stating that the State Board of Education's action aimed to protect the rights of Deaf consumers to choose a counselor who could sign or not sign. Consequently, the State Board of Education assigned Dr. Sanderson additional responsibilities, which included overseeing the entire Rehabilitation Services to the Deaf Program and providing training to all counselors and supervisors working with Deaf consumers. Additionally, the decision paved the way for the inclusion of a Deaf counselor in the Salt Lake area (The Silent Spotlight, June 1978).

Dr. Walter Talbot, the State Superintendent of Education, sought to reassure the Utah Deaf community by stating that the State Board of Education's action aimed to protect the rights of Deaf consumers to choose a counselor who could sign or not sign. Consequently, the State Board of Education assigned Dr. Sanderson additional responsibilities, which included overseeing the entire Rehabilitation Services to the Deaf Program and providing training to all counselors and supervisors working with Deaf consumers. Additionally, the decision paved the way for the inclusion of a Deaf counselor in the Salt Lake area (The Silent Spotlight, June 1978).