Biographies of Prominent

Utah Interpreters

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

In 1968, the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (URID) was founded by individuals with Deaf family members. Many leaders from the Utah Deaf community also joined the organization. Thanks to interpreter preparation programs, URID now has a large number of qualified interpreters. Today, interpreter training programs have expanded, and the demand for interpreters is still high. For aspiring interpreters, formal training programs are available at the Utah Interpreter Programs at the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Salt Lake Community College, Utah Valley University, and Utah State University. However, the ASL interpreting program at Davis Applied Technology College is no longer in operation. Previously, the VRS Interpreting Institute (VRSII) at Sorensen Communications provided training for new interpreting graduates, seasoned interpreters, and interpreter educators.

Religion, particularly The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has been a significant and enduring influence on Utah's history. This influence extends to the Utah Deaf community, making it an integral part of our collective heritage. The biographies of these interpreters, which often include their religious affiliations, provide a unique perspective on their lives and contributions. These biographies not only serve as a valuable resource for the interpreters' families, aiding in preserving history and exploring their lineage, but also contribute to the broader narrative of Utah's cultural and religious diversity. Furthermore, these biographies preserve the life stories of these individuals for future generations to appreciate and remember.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Finally, I would like to express my sincere gratitude towards the interpreters mentioned in their biographies for their tremendous dedication and accomplishments in the interpreting profession and the Utah Deaf community. Their relentless efforts have played a vital role in advocating for the passage of legislation recognizing American Sign Language as an official language in Utah, mandatory interpreter certification, and establishing the Utah Interpreter Program. These efforts have significantly improved the lives of the Utah Deaf community.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading the "Biographies of Prominent Utah Interpreters" webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Religion, particularly The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has been a significant and enduring influence on Utah's history. This influence extends to the Utah Deaf community, making it an integral part of our collective heritage. The biographies of these interpreters, which often include their religious affiliations, provide a unique perspective on their lives and contributions. These biographies not only serve as a valuable resource for the interpreters' families, aiding in preserving history and exploring their lineage, but also contribute to the broader narrative of Utah's cultural and religious diversity. Furthermore, these biographies preserve the life stories of these individuals for future generations to appreciate and remember.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Finally, I would like to express my sincere gratitude towards the interpreters mentioned in their biographies for their tremendous dedication and accomplishments in the interpreting profession and the Utah Deaf community. Their relentless efforts have played a vital role in advocating for the passage of legislation recognizing American Sign Language as an official language in Utah, mandatory interpreter certification, and establishing the Utah Interpreter Program. These efforts have significantly improved the lives of the Utah Deaf community.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading the "Biographies of Prominent Utah Interpreters" webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Background History

of Interpreting

of Interpreting

Prior to the late 1950s and early 1960s, there were no available sign language classes or interpreter training programs. The Utah Deaf community often relied on Children of Deaf Adults (CODAs) to serve as interpreters for various events and appointments, such as meetings and church activities. Interpreters, especially CODAs, volunteered for years until the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) was established in 1964. This information was shared by Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a former Director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf and a CODA who was born and raised in Utah (Stewart, UAD Bulletin, June 1973).

During the 1960s and 1970s, marginalized communities throughout the United States fought for social equality, which led to significant changes in the interpreting industry (Humphrey & Alcorn, 2001). The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) evolved to reflect the growing importance of professional interpreters as opposed to just "helpers" in the Code of Ethics, now known as the Code of Professional Conduct (Stewart, UAD Bulletin, June 1973). In Utah, the Deaf community relied on hard of hearing individuals who learned sign language before using hearing aids, as well as those who lost their hearing but developed strong oral communication skills. However, the number of Deaf people born deaf began to increase, while the percentage of individuals who later became deaf in Utah started to decline by 1961. Additionally, the number of Deaf people with multiple disabilities also grew during this time (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1961, p. 2). As a result, the Utah Deaf community needed more interpreting services, which eventually led to the creation of the RID organization to address their interpreting needs.

Lucy Pearl McMills Greenwood

Lucy McMills Greenwood was a sign language interpreter for more than 40 years, primarily at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf. She was a well-known interpreter and one of the first licensed professional interpreters in the country during the 1960s. She was an active member of both the Utah Association for the Deaf and the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Lucy was a strong advocate for the Utah Deaf community. Despite the challenges of raising a large family, Lucy received praise for her unwavering dedication to the field of sign language interpreting and her voluntary service to the Utah Deaf community.

Lucy Pearl McMills Greenwood was born on November 24, 1919, in Salt Lake City, Utah, to Deaf parents John Wallace McMills and Pearl Ault. John and Pearl were students at the Utah School for the Deaf in the early 1900s. They had two daughters, Lucy and Eva Alice (Fowler). Lucy's older brother, John Ault McMills, died shortly after birth.

Lucy's biography, written by the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, describes her happy childhood supporting her Deaf parents and playing with her sister Eva. Early instruction in sign language and finger spelling led to Lucy and Eva's rapid proficiency. As a child, Lucy attended school in the Salt Lake City District (LPMG Biography). They were extremely helpful to their parents, interpreting messages and assisting with their father's McMills Shoe Repair Shop (LPMG Biography). This shop was located at 267 E. 5th South in Salt Lake City, directly across the street from the Utah State Office of Education and near the Salt Lake City Police Department's driveway (Jean Thomas, personal communication, June 11, 2015).

Lucy went to her father's shoe shop every day after school to dye shoes. Her sister, Eva, did the majority of the interpreting. The police repeatedly searched for Eva and took her from work to interpret for Deaf people (Jean Thomas, personal communication, July 15, 2015).

Lucy (Greenwood) and Eva (Prudence) eventually became well-known interpreters in Utah (UAD Bulletin, February 1972).

Lucy (Greenwood) and Eva (Prudence) eventually became well-known interpreters in Utah (UAD Bulletin, February 1972).

Lucy was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. When she reached 18, the Relief Society invited her to participate in a program and dress up as the Bride of 1935. This was an unforgettable experience for her (LPMG Biography).

Lucy met her future husband, Virgil Rogers Greenwood, during a New Year's Eve dance and enjoyed chatting and dancing with him (LPMG Biography). He was deaf and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1931. Lucy and Virgil tied the knot in the Salt Lake Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints eight months later, on August 14, 1936. President George F. Richards, a Quorum of the Twelve Apostles member, performed the ceremony. He assured them they would live busy lives and leave a great legacy. His prediction came true when Lucy and Virgil became parents to nine children—five sons and four daughters (LPMG Biography). The children included Ruth Ann Greenwood (Felter), John Rogers Greenwood (who passed away at the age of 9), Virginia Ault Greenwood (Chambers), Virgil McMills Greenwood, Linda Alice Greenwood (Pepcorn), Jean Pearl Greenwood (Thomas), Charles Daniel Greenwood, Paul Francis Greenwood, and Timothy David Greenwood.

Lucy met her future husband, Virgil Rogers Greenwood, during a New Year's Eve dance and enjoyed chatting and dancing with him (LPMG Biography). He was deaf and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1931. Lucy and Virgil tied the knot in the Salt Lake Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints eight months later, on August 14, 1936. President George F. Richards, a Quorum of the Twelve Apostles member, performed the ceremony. He assured them they would live busy lives and leave a great legacy. His prediction came true when Lucy and Virgil became parents to nine children—five sons and four daughters (LPMG Biography). The children included Ruth Ann Greenwood (Felter), John Rogers Greenwood (who passed away at the age of 9), Virginia Ault Greenwood (Chambers), Virgil McMills Greenwood, Linda Alice Greenwood (Pepcorn), Jean Pearl Greenwood (Thomas), Charles Daniel Greenwood, Paul Francis Greenwood, and Timothy David Greenwood.

Virgil and Lucy resided in Roy until the early 1940s. When they first got married, Virgil was a farmer in Roy, Utah. He owned a little farm and converted his chicken coop into their small one-room home (which still stands today) on the northwest corner of 5600 South and 3100 West. They grew vegetables and chickens. Virgil worked on a huge 40-acre farm for his father, Ruben Percy Greenwood (his mother was Ethel Melissa Rogers), milking 36 cows by hand twice daily. He was employed to work for other Roy farmers. Delos W. Holly, a farmer, told Jean in 1974 that everyone wanted to hire the Greenwoods because they were hard workers and good farmers (Jean Thomas, personal communication, June 11, 2015).

Virgil was the oldest of five children, born to Ruben P. and Ethel M. Rogers Greenwood. Virgil had three brothers and one sister. Bert was the second child; he was deaf and attended public school in Roy, Utah. Stewart was the third child; he was deaf and attended Utah School for the Deaf. An automobile in Roy struck Stewart, who was 23 years old, while he was returning from a dance in Ogden, Utah. Arden was Roy's fourth child who could hear and went to public school. Gloria was the youngest child to attend the Utah School for the Deaf. However, her mother wanted her to learn to speak, so Ethel sent Gloria to live with her sister, Maud Rogers Taylor, in Provo, Utah, from time to time, learning to talk from a teacher who resided there. Ethel Rogers Greenwood notes in her diary that her children all had terrible ear infections from birth, which caused their deafness (Jean Thomas, personal communication, April 9, 2019).

Virgil was the oldest of five children, born to Ruben P. and Ethel M. Rogers Greenwood. Virgil had three brothers and one sister. Bert was the second child; he was deaf and attended public school in Roy, Utah. Stewart was the third child; he was deaf and attended Utah School for the Deaf. An automobile in Roy struck Stewart, who was 23 years old, while he was returning from a dance in Ogden, Utah. Arden was Roy's fourth child who could hear and went to public school. Gloria was the youngest child to attend the Utah School for the Deaf. However, her mother wanted her to learn to speak, so Ethel sent Gloria to live with her sister, Maud Rogers Taylor, in Provo, Utah, from time to time, learning to talk from a teacher who resided there. Ethel Rogers Greenwood notes in her diary that her children all had terrible ear infections from birth, which caused their deafness (Jean Thomas, personal communication, April 9, 2019).

Virgil later left the farm to make a living. He was the state's first Deaf employee. In the beginning, he worked as a mechanic on B-52 bombers at Hill Air Force Base, where he created a system that allowed a mechanic to work on the engine and rotate it as needed for repair. He eventually transferred to the Utah Defense Depot in Ogden (DDO) to be closer to home; at the time, they resided on Gwen Street in Ogden, just around the street from Frank and Orba Seeley (Deaf friends). Virgil walked to work every day until they relocated to Washington Boulevard in Ogden, and then he took the bus to and from work. He did this so Lucy would have a car and be able to go and interpret for her friends as needed (Jean Thomas, personal communication, June 11, 2015).

Soon after Vigil and Lucy married, they settled in Roy, Utah, and attended services at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah. According to her obituary, her lifelong service involved church services and interpreting for the deaf. Lucy spent 62 years as a trusted friend and interpreter in the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, 27 years as Young Women's President, an instructor and visiting teacher for the Relief Society, and a full-time mission to the deaf in Chicago, Illinois. The LDS Church invited Lucy to assist with several special projects, such as the establishment of the first mission training center for the deaf, special Temple projects, General Conference interpreting, and the translation of numerous LDS films into American Sign Language (UAD Bulletin, August 2011).

President Max W. Woodbury of Ogden Branch frequently asked Lucy to translate for speakers. In 1946, President Woodbury requested that Lucy serve as President of the Young Women's Mutual Improvement Association (YWMIA) at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf. She served faithfully for 23 years. On November 5, 1956, the Relief Society at the Ogden Branch called Lucy a theology instructor. She taught this class faithfully for three years despite the demands on her time and energy from outside responsibilities (Ogden Branch records; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, July 27, 2011).

President Max W. Woodbury of Ogden Branch frequently asked Lucy to translate for speakers. In 1946, President Woodbury requested that Lucy serve as President of the Young Women's Mutual Improvement Association (YWMIA) at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf. She served faithfully for 23 years. On November 5, 1956, the Relief Society at the Ogden Branch called Lucy a theology instructor. She taught this class faithfully for three years despite the demands on her time and energy from outside responsibilities (Ogden Branch records; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, July 27, 2011).

Lucy's demand as an interpreter, chorister, substitute teacher, substitute secretary, and various other odd jobs grew over time. She interpreted for numerous young Deaf couples married at the temple. She also interpreted for several Deaf people working in the temple. She was also an interpreter at Weber College (later renamed Weber State University) (LPMG Biography). Lucy served as a loyal interpreter for his classes from 1969 to 1971, according to G. Leon Curtis, a Deaf Weber College student, and provided positive advice and support. He told her that after he graduated from Weber College, she should get a special degree from this college for interpreting and learning with him for three years (G. Leon Curtis, personal communication, July 27, 2011).

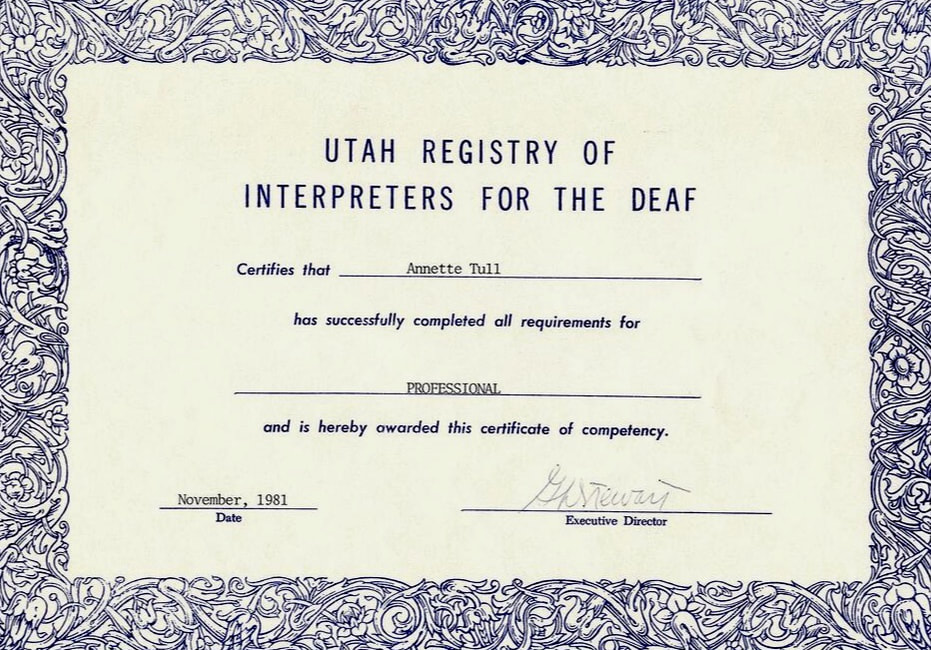

Lucy became one of the first interpreters to join the newly formed Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf on October 5, 1968 (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1968). She was also one of thirteen interpreters who completed the Utah Registry of Interpreters state certification on November 16, 1975 (UAD Bulletin, April 1975). After founding the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in 1968, Lucy gained recognition as Utah's senior interpreter in the 1970s.

Lucy has worked as an interpreter for the deaf for over forty years, primarily at the Ogden Branch. She earned a reputation for her work and became one of the first certified interpreters in the country. She was also a member of the Utah Association for the Deaf and the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (LPMG Biography). Her two daughters, Jean Thomas and Ruth Ann Felter, later followed in her footsteps and became interpreters (UAD Bulletin, May 1992).

Lucy became one of the first interpreters to join the newly formed Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf on October 5, 1968 (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1968). She was also one of thirteen interpreters who completed the Utah Registry of Interpreters state certification on November 16, 1975 (UAD Bulletin, April 1975). After founding the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in 1968, Lucy gained recognition as Utah's senior interpreter in the 1970s.

Lucy has worked as an interpreter for the deaf for over forty years, primarily at the Ogden Branch. She earned a reputation for her work and became one of the first certified interpreters in the country. She was also a member of the Utah Association for the Deaf and the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (LPMG Biography). Her two daughters, Jean Thomas and Ruth Ann Felter, later followed in her footsteps and became interpreters (UAD Bulletin, May 1992).

Jean, Lucy's daughter, recalls her mother, Lucy, preparing for the 1960s National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf test. Her clothes were changed into black, dark brown, navy blue, and other dark colors. Lucy and her sister, Eva, would talk about taking the RID test and how nervous she was, fearing she would fail. "Now, Lucy," Eva would remark, "you will pass; just be calm!" She took interpreting very seriously. She was the Utah State proctor for the RID test until around 1990, when Annette Thorpe Tull, also a CODA and interpreter, asked her if she could take on that job for the state of Utah. Lucy firmly believed in the Interpreter Code of Ethics and talked to and educated Jean about it for many years. "Jeannie, the Deaf need to know that they have their privacy and can trust you with information about their lives that you have no right to," Lucy stated. Lucy practically dragged Jean to the interpretation classes in her diapers. For many years, Jean went to courses with her mother every Saturday. Jean recalls sitting in a wide circle with numerous CODAs, including Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's sons, Gary and Barry. "It was historic when Bob Sanderson was in charge of the training," she said, "and the training was marvelous." Jean has pleasant recollections of collaborating with her mother to interpret. She came to value her mother's background and the legacy she had left for interpreters everywhere (Jean Thomas, personal communication, July 15, 2015).

Lucy was an officer and member of the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. She was instrumental in developing the state of Utah's first sign language interpreting certification. She also worked as a certification evaluator and proctor for three organizations: the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, the Interpreter Certification Board, and the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (LPMG Biography).

Lucy was an officer and member of the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. She was instrumental in developing the state of Utah's first sign language interpreting certification. She also worked as a certification evaluator and proctor for three organizations: the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, the Interpreter Certification Board, and the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (LPMG Biography).

Lucy's work as an interpreter was mostly voluntary. The state of Utah established a budget for interpreting service fees in the late 1970s. She frequently expressed her gratitude for the opportunity to assist others. It was never a question of whether she should serve, but simply when, where, and how (LPMG Biography). Jean, Lucy's daughter, said that her mother, Lucy, interpreted from an early age until 2002. She worked as an interpreter for the Utah School for the Deaf and other community organizations until her late eighties. Lucy had huge ganglion cysts on both her hands, and she refused surgery when Jean tried to persuade her mother to have them removed because they were causing her so much pain. Lucy answered, "NO, I WILL NEVER BE ABLE TO INTERPRET OR TALK TO MY DEAF BROTHERS AND SISTERS AGAIN." She remained a certified registered member of the RID until around 2005. She loved the Utah Deaf community and referred to herself as DEAF. Jean could see Lucy had a "Deaf Heart" (Jean Thomas, personal communication, July 15, 2015).

Lucy passed away on July 21, 2011, at 91, in Rupert, Idaho, at the home of one of her daughters, Linda. Following the burial in Ogden, she was laid to rest with her husband, Virgil, who passed in August 1973, and her parents, John and Pearl McMills, in the Salt Lake City Cemetery in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her two boys, John Rogers and Charles Daniel, were buried there, as were her sister, Eva Alice McMills Prudence Fowler, and Eve's husband, Daniel E. Prudence. Jean Thomas of Roy, Ruth Ann Felter of Layton, and Linda Popcorn of Rupert, Idaho, are among her children (UAD Bulletin, August 2011). Lucy's two other boys, Paul Francis and Timothy David of Utah, are survivors (Jean Thomas, personal communication, July 15, 2015).

Lucy pioneered sign language interpreting and was a passionate advocate for the Utah Deaf community. She was involved in numerous volunteer efforts, though it's impossible to include them all here. Despite the demands of raising a large family, Lucy remained dedicated to her work as an interpreter. She also committed to giving back to the Utah Deaf community, particularly the Ogden Branch for the Deaf. Her tireless efforts and selfless service are truly commendable.

Lucy passed away on July 21, 2011, at 91, in Rupert, Idaho, at the home of one of her daughters, Linda. Following the burial in Ogden, she was laid to rest with her husband, Virgil, who passed in August 1973, and her parents, John and Pearl McMills, in the Salt Lake City Cemetery in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her two boys, John Rogers and Charles Daniel, were buried there, as were her sister, Eva Alice McMills Prudence Fowler, and Eve's husband, Daniel E. Prudence. Jean Thomas of Roy, Ruth Ann Felter of Layton, and Linda Popcorn of Rupert, Idaho, are among her children (UAD Bulletin, August 2011). Lucy's two other boys, Paul Francis and Timothy David of Utah, are survivors (Jean Thomas, personal communication, July 15, 2015).

Lucy pioneered sign language interpreting and was a passionate advocate for the Utah Deaf community. She was involved in numerous volunteer efforts, though it's impossible to include them all here. Despite the demands of raising a large family, Lucy remained dedicated to her work as an interpreter. She also committed to giving back to the Utah Deaf community, particularly the Ogden Branch for the Deaf. Her tireless efforts and selfless service are truly commendable.

Notes

G. Leon Curtis, personal communication, July 27, 2011.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, June 11, 2015.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, July 15, 2015.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, April 9, 2019

Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, July 27, 2011.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, June 11, 2015.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, July 15, 2015.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, April 9, 2019

Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, July 27, 2011.

References

Biography of Lucy Pearl McMills Greenwood, March 1973.

Felter, Ann. “Five Generations.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 12 (May 1992): 2.

“Local News: Lucy Greenwood.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 35.023 (August 2011): 3.

Ogden Branch records.

“Organization of Utah Registry of Interpreter for the Deaf.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 3 (Fall 1968): 1.

“Salt Shaker.” UAD Bulletin, vol.7, no. 4 (February 1972): 4.

“URID Certifies Interpreters in Workshop.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 1 (April 1975): 1.

Felter, Ann. “Five Generations.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 12 (May 1992): 2.

“Local News: Lucy Greenwood.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 35.023 (August 2011): 3.

Ogden Branch records.

“Organization of Utah Registry of Interpreter for the Deaf.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 3 (Fall 1968): 1.

“Salt Shaker.” UAD Bulletin, vol.7, no. 4 (February 1972): 4.

“URID Certifies Interpreters in Workshop.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 1 (April 1975): 1.

Beth Ann Stewart Campbell

Beth Ann Stewart Campbell was a remarkable woman who achieved the distinction of becoming the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States in 1965. From that point on, she became a pioneer in interpreting. Beth Ann was the first hearing woman to be elected to the Board of Directors of the Utah Association for the Deaf, and she also coined the term "co-therapist" as the first interpreter to work with both the psychiatrist and the patient. She was appointed Director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf in Bountiful, Utah, in 1985, and she went above and beyond in delivering excellent community service for many years. Her contributions had a significant impact on deaf-related services and the interpreting system. Beth Ann's achievement of being the first nationally certified interpreter in Utah and the United States is a great honor for the Utah Deaf community and the Utah interpreting community.

Beth Ann Moon Stewart Campbell was born on December 9, 1937, at Murray Maternity Hospital to Deaf parents Arnold Moon and Zelma Lindquist. Beth Ann, also known as "B.A.," is a prominent figure in the Utah Deaf community (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992). Arnold Henry Moon, Beth Ann's father, was born on March 7, 1905, in Woodland, Utah. Beth Ann and her family believe he was born deaf. At the age of six, Arnold enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) in Ogden, Utah. Arnold's mother supported him and helped him with his studies. He graduated from the USD in 1928 and worked as a shoe repairman. Beth Ann believes he learned shoe repair while attending the Utah School for the Deaf. Arnold was also a skilled basketball player for the school (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Zelma Lindquist was born in West Jordan, Utah, on January 6, 1908. She was born with measles and contracted diphtheria when she was two, which caused her to become deaf. When she was two and a half years old, her parents enrolled her at the Utah School for the Deaf, and she graduated from the school in 1928. Zelma was an excellent seamstress, and it is believed that she studied sewing at the school, according to Beth Ann Campbell (personal communication, September 18, 2012). During that time, students at the Utah School for the Deaf only went home during holidays throughout the year, and they were taught regular academic subjects and homemaking skills. They learned essential skills such as cleaning, sewing, and cooking while they were there.

Zelma Lindquist was born in West Jordan, Utah, on January 6, 1908. She was born with measles and contracted diphtheria when she was two, which caused her to become deaf. When she was two and a half years old, her parents enrolled her at the Utah School for the Deaf, and she graduated from the school in 1928. Zelma was an excellent seamstress, and it is believed that she studied sewing at the school, according to Beth Ann Campbell (personal communication, September 18, 2012). During that time, students at the Utah School for the Deaf only went home during holidays throughout the year, and they were taught regular academic subjects and homemaking skills. They learned essential skills such as cleaning, sewing, and cooking while they were there.

The Utah School for the Deaf had many Deaf students, which facilitated them to form lifelong friendships. Arnold and Zelma met at this school and began dating. They married on June 19, 1929. They initially lived in Hanna, Utah, where they tragically lost their two older sons, Delbert and Deloy. They later moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, where they found better employment opportunities and social connections with other Deaf individuals. Beth Ann, their daughter, grew up in a hardworking family and was provided for by her parents, alongside her older sister, Marjorie. "Sign language" was Beth Ann's primary language, which she learned from her parents at home while also picking up English from her playmates, the radio, and her relatives. She has no recollection of not being able to sign or speak English and enjoyed spending time with other friends (Beth Ann Campbell, personal conversation, September 18, 2012).

As a hearing child of Deaf parents, Beth Ann had the responsibility to assist them with interpreting, as was customary for hearing children of Deaf parents at the time. She went above and beyond what her older sister did, making phone calls for her parents. Because they didn't have a phone at the time, she had to go to her neighbors and ask if she could use their phone to make doctor appointments, get medicine, and take care of other things. Sometimes, she felt embarrassed when making certain adult phone calls at her neighbor's house while everyone was listening in on what would normally be considered a "private conversation." She dislikes using the phone now because she felt forced to use it as a child and young adult (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

As a hearing child of Deaf parents, Beth Ann had the responsibility to assist them with interpreting, as was customary for hearing children of Deaf parents at the time. She went above and beyond what her older sister did, making phone calls for her parents. Because they didn't have a phone at the time, she had to go to her neighbors and ask if she could use their phone to make doctor appointments, get medicine, and take care of other things. Sometimes, she felt embarrassed when making certain adult phone calls at her neighbor's house while everyone was listening in on what would normally be considered a "private conversation." She dislikes using the phone now because she felt forced to use it as a child and young adult (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann has been providing interpreting services to the Deaf community in Utah since 1963. Her achievement as the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States is historically significant. Inspired by Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, president of the National Association of the Deaf and one of the first participants of the newly formed Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in 1964, Beth Ann, a Utah native and Child of Deaf Adults (CODA), took the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf certification exam. As a result, in 1965, she became the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States, a remarkable milestone that paved the way for the interpreting profession. Notably, Beth Ann obtained her first certification a year after the official recognition of the National Registry of Interpreters of the Deaf, which was founded in 1964, and six years before its incorporation in 1972. Here's her story.

In 1965, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell made history as the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States, laying the groundwork for the interpreting profession. The RID, founded in 1964, is a professional organization that promotes the profession of interpreting and transliterating American Sign Language and English. Her journey, marked by courage and determination, began in 1963 when her first husband, Wayne Stewart, a police officer, asked for her help in interpreting for a Colorado-based Deaf man who was experiencing mistreatment at the Salt Lake City Police Department. Beth Ann, feeling unsure about her skills, contacted several interpreters for assistance with interpreting. However, because they were already working, they were unavailable. One of her friends, who was an interpreter, encouraged Beth Ann to lend a hand. Despite feeling scared, Beth Ann bravely went to the police station. There, she found the Deaf man chained up and terrified. The police station left her alone with him, and soon, they were able to communicate effectively so that she could help him. Eventually, they placed him on a bus back to Colorado (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). It was her first time interpreting outside her home.

In 1965, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell made history as the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States, laying the groundwork for the interpreting profession. The RID, founded in 1964, is a professional organization that promotes the profession of interpreting and transliterating American Sign Language and English. Her journey, marked by courage and determination, began in 1963 when her first husband, Wayne Stewart, a police officer, asked for her help in interpreting for a Colorado-based Deaf man who was experiencing mistreatment at the Salt Lake City Police Department. Beth Ann, feeling unsure about her skills, contacted several interpreters for assistance with interpreting. However, because they were already working, they were unavailable. One of her friends, who was an interpreter, encouraged Beth Ann to lend a hand. Despite feeling scared, Beth Ann bravely went to the police station. There, she found the Deaf man chained up and terrified. The police station left her alone with him, and soon, they were able to communicate effectively so that she could help him. Eventually, they placed him on a bus back to Colorado (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). It was her first time interpreting outside her home.

Beth Ann's remarkable achievement of becoming the first nationally certified interpreter in 1965 also began with Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent figure in the Utah Deaf community and the president of the National Association of the Deaf from 1964 to 1968. He participated as a consultant in a workshop on 'Interpreting for the Deaf' in Muncie, Indiana, in 1964. After the workshop, he wrote a letter to Deaf parents, urging them to inform their "Child of Deaf Adults" (CODA) children about an upcoming interpreting conference (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1964). During an interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010, Beth Ann shared that her mother showed her the flyer about a conference for children of Deaf adults. They were looking to recruit and train interpreters in Utah. Her mother convinced Beth Ann, who had six children at the time, to attend the conference.

During the conference, Beth Ann witnessed an interpreter at work for the first time. Even though she had been using sign language her whole life, this experience helped her understand the difference between communication and interpreting. This event was eye-opening for her. She never thought she would one day become an interpreter. Her life changed forever when Bob Sanderson called Beth Ann, who was on the conference participant list, and asked her to interpret for him at the court. She agreed and went (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012). After this experience, Beth Ann devoted her life with unwavering commitment and passion to interpreting and advocating for the Deaf community in Utah. She has dedicated her career to working with Deaf individuals and providing interpretation services in various settings, such as the legislature, court, mental health, medical, and higher education. Beth Ann was the first interpreter at the University of Utah. She also worked full-time for the Utah Division of Rehabilitation and volunteered to interpret the evening news on television from 1971 to 1980.

During his time as NAD president, Dr. Sanderson played a significant role in motivating and supporting Beth Ann to pursue certification as an interpreter. He encouraged her to take the national certification exam at the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in Illinois in 1965. While people from various states traveled to Illinois for the exam, Beth Ann was the only one from Utah to participate (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann's achievement of becoming the first certified interpreter was not just a personal success but a significant milestone for the Deaf community and the interpreting profession. In the March 1992 UAD Bulletin, Beth Ann's second husband, Dr. Jay J. Campbell, explained that the selection and certification of interpreters were part of a nationwide training process. He went on to explain how Beth Ann became the first one to take the certification test. The program required each participant to take a test. The testing order was determined by drawing straws, which was a nerve-wracking experience. Being the first to take the test meant setting the standard for all future interpreters. During the drawing process, the woman sitting next to Beth Ann was picked first, and Beth Ann was tested last. The woman said she didn't want to be the first to take the test, and Beth Ann, understanding the significance of this opportunity and the responsibility that came with it, responded by saying she didn't want to be the last one. After exchanging numbers, Beth Ann took the test first and passed it, becoming the first nationally certified interpreter in Utah and the United States (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). Since obtaining her certification in 1965, Beth Ann has been a trailblazer in the field of interpreting. Her achievement is a testament to her courage, determination, and the respect she holds in the interpreting field. It paved the way for future interpreters and raised awareness of the importance of interpreting in the Deaf community.

Beth Ann has made significant contributions to the profession and is a strong advocate for the Utah Deaf community. Her dedication and achievements have earned her widespread respect and appreciation. Utah is fortunate to have her as the first certified interpreter in the United States. Her achievement has paved the way for many others in the field and opened doors for future interpreters. Her achievements have significantly improved the quality of life for the Deaf community, ensuring their voices were heard and understood.

In 1970, when W. David "Dave" Mortensen, a Utah Deaf leader and the long-time president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, was studying at the University of Utah, he required the services of a part-time interpreter. Beth Ann, a freelance interpreter, was hired to work with him. This was the first time the university had used an interpreter. Both Beth Ann and David were initially quite nervous, but they improved with time. Beth Ann Campbell was the first interpreter to assist Dave with interpreting at the university (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann was a freelance interpreter for the Utah Division of Rehabilitation in 1972. At that time, Dr. Sanderson, who was a statewide coordinator for Deaf adults at the Utah Division of Rehabilitation, needed a full-time interpreter. He invited Beth Ann to meet him and offered her a job. Although Beth Ann loved her job with W. David Mortensen, she asked Dr. Sanderson if she could do both jobs. However, Dr. Sanderson said she would have to leave her job with Dave if she worked for him full-time. Beth Ann then worked full-time for Dr. Sanderson (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012). Her first responsibility was assisting him with interpreting and accompanying him to all the meetings he was responsible for attending. Beth Ann acknowledges that Dr. Sanderson was her mentor and teacher. He was patient, kind, and a great boss (UAD Bulletin, April 1992). Dr. Sanderson complimented Beth Ann by saying that his "long-suffering and patient interpreter and colleague, a tenacious advocate of the deaf, was always ready" (Sanderson, 2004).

During the conference, Beth Ann witnessed an interpreter at work for the first time. Even though she had been using sign language her whole life, this experience helped her understand the difference between communication and interpreting. This event was eye-opening for her. She never thought she would one day become an interpreter. Her life changed forever when Bob Sanderson called Beth Ann, who was on the conference participant list, and asked her to interpret for him at the court. She agreed and went (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012). After this experience, Beth Ann devoted her life with unwavering commitment and passion to interpreting and advocating for the Deaf community in Utah. She has dedicated her career to working with Deaf individuals and providing interpretation services in various settings, such as the legislature, court, mental health, medical, and higher education. Beth Ann was the first interpreter at the University of Utah. She also worked full-time for the Utah Division of Rehabilitation and volunteered to interpret the evening news on television from 1971 to 1980.

During his time as NAD president, Dr. Sanderson played a significant role in motivating and supporting Beth Ann to pursue certification as an interpreter. He encouraged her to take the national certification exam at the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in Illinois in 1965. While people from various states traveled to Illinois for the exam, Beth Ann was the only one from Utah to participate (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann's achievement of becoming the first certified interpreter was not just a personal success but a significant milestone for the Deaf community and the interpreting profession. In the March 1992 UAD Bulletin, Beth Ann's second husband, Dr. Jay J. Campbell, explained that the selection and certification of interpreters were part of a nationwide training process. He went on to explain how Beth Ann became the first one to take the certification test. The program required each participant to take a test. The testing order was determined by drawing straws, which was a nerve-wracking experience. Being the first to take the test meant setting the standard for all future interpreters. During the drawing process, the woman sitting next to Beth Ann was picked first, and Beth Ann was tested last. The woman said she didn't want to be the first to take the test, and Beth Ann, understanding the significance of this opportunity and the responsibility that came with it, responded by saying she didn't want to be the last one. After exchanging numbers, Beth Ann took the test first and passed it, becoming the first nationally certified interpreter in Utah and the United States (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). Since obtaining her certification in 1965, Beth Ann has been a trailblazer in the field of interpreting. Her achievement is a testament to her courage, determination, and the respect she holds in the interpreting field. It paved the way for future interpreters and raised awareness of the importance of interpreting in the Deaf community.

Beth Ann has made significant contributions to the profession and is a strong advocate for the Utah Deaf community. Her dedication and achievements have earned her widespread respect and appreciation. Utah is fortunate to have her as the first certified interpreter in the United States. Her achievement has paved the way for many others in the field and opened doors for future interpreters. Her achievements have significantly improved the quality of life for the Deaf community, ensuring their voices were heard and understood.

In 1970, when W. David "Dave" Mortensen, a Utah Deaf leader and the long-time president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, was studying at the University of Utah, he required the services of a part-time interpreter. Beth Ann, a freelance interpreter, was hired to work with him. This was the first time the university had used an interpreter. Both Beth Ann and David were initially quite nervous, but they improved with time. Beth Ann Campbell was the first interpreter to assist Dave with interpreting at the university (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann was a freelance interpreter for the Utah Division of Rehabilitation in 1972. At that time, Dr. Sanderson, who was a statewide coordinator for Deaf adults at the Utah Division of Rehabilitation, needed a full-time interpreter. He invited Beth Ann to meet him and offered her a job. Although Beth Ann loved her job with W. David Mortensen, she asked Dr. Sanderson if she could do both jobs. However, Dr. Sanderson said she would have to leave her job with Dave if she worked for him full-time. Beth Ann then worked full-time for Dr. Sanderson (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012). Her first responsibility was assisting him with interpreting and accompanying him to all the meetings he was responsible for attending. Beth Ann acknowledges that Dr. Sanderson was her mentor and teacher. He was patient, kind, and a great boss (UAD Bulletin, April 1992). Dr. Sanderson complimented Beth Ann by saying that his "long-suffering and patient interpreter and colleague, a tenacious advocate of the deaf, was always ready" (Sanderson, 2004).

Beth Ann was one of the first hearing people to join the Utah Association for the Deaf (UAD) when Utah broke precedent by changing the name of the association from "of" to "for" in 1963 to allow hearing individuals to join the board (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1963, p. 2). Dr. Jay J. Campbell noted in the UAD Bulletin's March 1992 issue that "Beth Ann is well known in the UAD." The association assigned her as a secretary to W. David Mortensen upon his initial appointment as UAD president in 1971. She was an active board member for many years" (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992).

On October 5, 1968, Beth Ann was one of the interpreters who assisted in establishing the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. She was elected secretary (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1968).

On October 5, 1968, Beth Ann was one of the interpreters who assisted in establishing the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. She was elected secretary (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1968).

Officers of the Utah Association for the Deaf, 1971. Front row L-R:: Jerry Taylor, treasurer, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, secretary, Lloyd Perkins, vice president, David Mortensen, president, Ned Wheeler, chairman. Back row L-R: Robert Welsh, Leon Curtis, Kenneth Burdett, Dennis Platt, Gene Stewart, Robert Sanderson

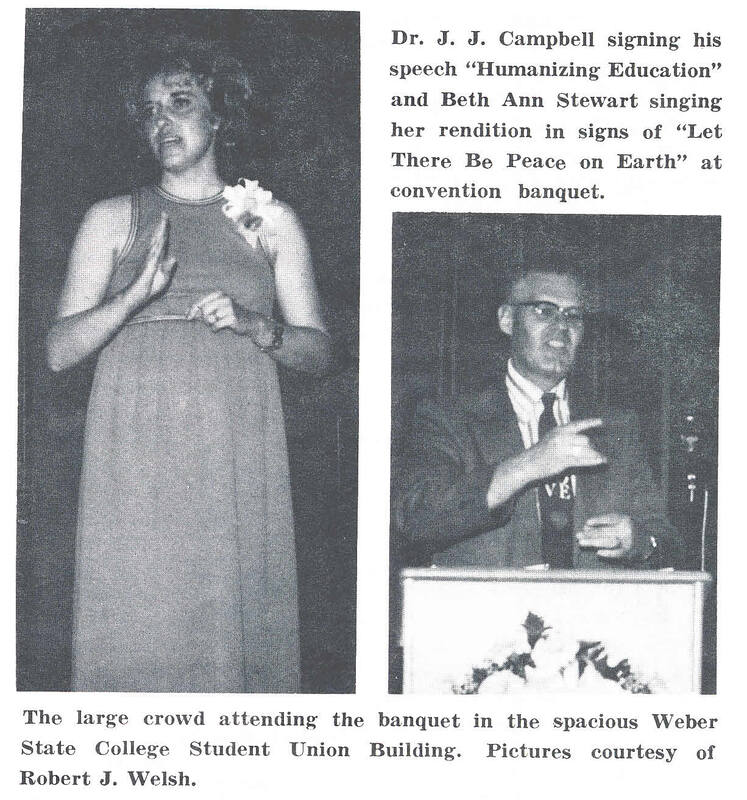

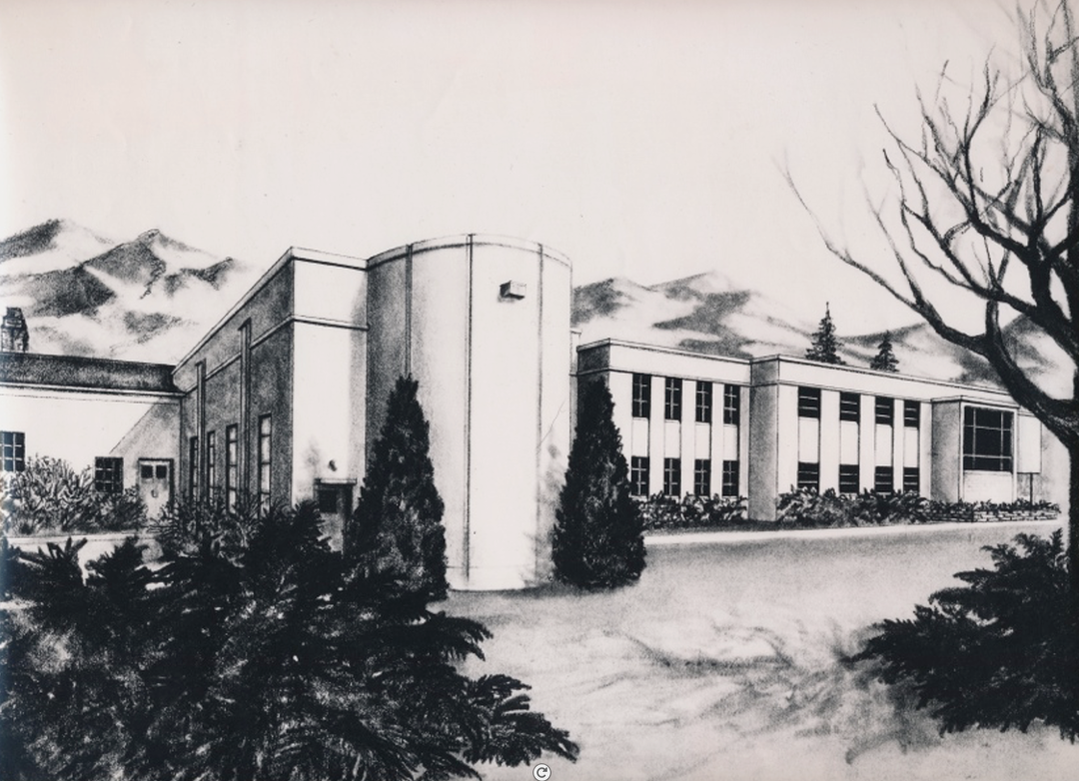

In 1966, Dr. Jay J. Campbell was hired by the Utah State Board of Education as an associate superintendent with the Utah State Office of Education. One of his responsibilities was to oversee the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. During the debate over oral versus total communication, he grew concerned with the welfare of Deaf children (Campbell, 1977). W. David Mortensen, president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, invited Dr. Campbell to speak at the UAD convention in January 1973. He asked Beth Ann, who was then UAD secretary, to assist him in interpreting. Beth Ann and Dave visited with Dr. Campbell, and he agreed to speak at the convention six months later. Dr. Campbell decided to give his presentation in sign language, so he asked Dr. Sanderson, Beth Ann's boss if someone could teach him enough signs to deliver his speech. Dr. Sanderson appointed Beth Ann to teach him. She accepted the challenge and became great friends with Dr. Campbell (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012). Dr. Campbell delivered his full "Humanizing Education" speech in sign language at the 25th Biennial Convention on June 16, 1973. "I presented a ten-minute talk that took me 30 minutes to deliver in signs," he said (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Three years later, on March 20, 1976, Dr. Campbell and Beth Ann were married by their local bishop and were sealed in the Manti Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on September 5, 1981. Beth Ann's children are Mark, Dennis, Steve, Michael, Michelle (Brown), and Gregory. Jay's children are Candice, John, Tamara, Woodrow, and Nola. Beth Ann has nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Jay has twelve grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. When people ask how many children they have, they answer, "Five and a half dozen." They then explain that "Jay has five, and Beth Ann has a half dozen." Their children are from their first marriages (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann's interpreting tasks grew significantly over time. According to "The Deaf Education History in Utah," during the rapid growth of the oral and mainstreaming movements and the decline of sign language in the educational system in the 1970s, Beth Ann often assisted Dr. Sanderson and W. David Mortensen, Deaf Education Advocates, with interpreting. They fought relentlessly against those who advocated for oral deaf education methods. Dr. Campbell, then the associate superintendent, published "Education of the Deaf in Utah: A Comprehensive Study" in 1977 to address the ongoing controversy over oral vs. total communication. However, this result sparked debate among parents who campaigned for oral education. As a result, Dr. Campbell's plan came crashing down. His two-year study, which included recommendations for improving education through fair assessment and placement procedures, was buried and forgotten (Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

In 1975, Beth Ann traveled to Los Angeles, California, with four Utah Deaf volunteers to serve as an interpreter while touring the Ear Research Institute, where one of the volunteers, Joseph B. Burnett, 62, received his new cochlear implant (UAD Bulletin, June 1974). Beth Ann had the opportunity to witness this moment when Joe became the world's first Deaf person to receive cochlear implants (Kinney, UAD Bulletin, November 2001; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

From 1971 to 1980, Beth Ann volunteered as an interpreter for Channel 4 News in sign language on the right corner of the television screen. The Utah Deaf community remembered seeing her on the news (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992). A February 1972 photo from the UAD Bulletin shows Beth Ann interpreting the news.

When Dr. Sanderson retired as director of the Utah Community Center of the Deaf (UCCD) in 1985, he noted in his book, "A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing," that Beth Ann would become the new director:

"Dr. Judy Ann Buffmire, Executive Director of the Utah Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services, appointed Beth Ann as Director of the Utah Community Center of the Deaf. Beth Ann had worked as a professional interpreter and aide for the Division of Rehabilitation for over 15 years and was closely associated with the Center for the Deaf programs. She was also a "CODA" and enjoyed considerable support among the deaf community, reflecting her advocacy and activism on behalf of deaf people (Sanderson, 2004)."

Beth Ann served as the director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf in Bountiful, Utah, until she retired on March 13, 1992. Prior to her directorship, she worked as an interpreter for many years, covering courts, lawyers, doctors, therapists, meetings, and other events requiring interpreters (Emery, Davis County, & Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 25, 1990). She also helped Deaf leaders lobby for funding for the Utah Community Center for the Deaf. According to the "History of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing" webpage, Beth Ann's assistance with interpreting was essential in overcoming communication barriers and securing funds for the center during the legislative process.

"Dr. Judy Ann Buffmire, Executive Director of the Utah Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services, appointed Beth Ann as Director of the Utah Community Center of the Deaf. Beth Ann had worked as a professional interpreter and aide for the Division of Rehabilitation for over 15 years and was closely associated with the Center for the Deaf programs. She was also a "CODA" and enjoyed considerable support among the deaf community, reflecting her advocacy and activism on behalf of deaf people (Sanderson, 2004)."

Beth Ann served as the director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf in Bountiful, Utah, until she retired on March 13, 1992. Prior to her directorship, she worked as an interpreter for many years, covering courts, lawyers, doctors, therapists, meetings, and other events requiring interpreters (Emery, Davis County, & Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 25, 1990). She also helped Deaf leaders lobby for funding for the Utah Community Center for the Deaf. According to the "History of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing" webpage, Beth Ann's assistance with interpreting was essential in overcoming communication barriers and securing funds for the center during the legislative process.

Beth Ann, director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf in Bountiful, Utah, highlighted the activities that were part of the educational and social events that took place at the UCCD:

- Cooking Classes. Many of the young Deaf mothers had very little experience in this area. UCCD brought in people from the community to teach cooking classes of all kinds.

- Income Tax Preparation. Experts in this field were solicited, and they gave of their time without pay to teach the deaf how to prepare their tax returns.

- Women on Target. Beth Ann conducted this class. Most Deaf women wanted to improve their parenting and social skills. These classes became very popular.

- Lectures. Beth Ann went to the public and asked professional people to come and speak to Deaf consumers. They covered any subjects that the Deaf wanted. She was truly surprised and happy to see how many "hearing" people were willing to come and offer their expertise to the deaf.

- Athletic Events. Deaf people loved athletics.

- Senior Citizen Lunches and Outings. The staff at the Center prepared a monthly luncheon for their senior citizens. This was a popular event, and a big turnout occurred monthly.

- Parenting Classes. Young married couples were more than pleased to have classes available to learn how to be effective parents.

- Socials. It was probably the most successful thing they did during Beth Ann's tenure. Under her leadership, the staff would recommend a theme for an upcoming social and then turn it over to the deaf to plan, set up committees to paint decorations (They had several great artists), build booths, advertise, and put on these social events. It was always a great event, and the Deaf community supported these socials. There was always good food, and sometimes dancing.

- Utah Organizations. Beth Ann coordinated with the Utah Organizations to send out a yearly calendar of activities throughout the state.

- Monthly Newsletter. This was published and distributed throughout the state to keep the deaf informed of the activities at the UCCD and other things of interest to the deaf.

- Money Contributions. There was a need to raise money for things needed at the Center. As the spokesman for the Center, Beth Ann asked many organizations to contribute money to help purchase needed items. They raised approximately $80,000, and the Telephone Company painted the building and fixed the bathroom.

During her time working for Dr. Sanderson and later as director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, Beth Ann received the following awards:

- Division of Rehabilitation Services, 1986. For Exemplary Program Continuation and Development on Behalf of Deaf/Hearing Impaired People of Utah. Presented to Beth Ann Campbell.

- Golden Key Award. October 7, 1987. Beth Ann Campbell, Service Provider. For Your Exemplary Service to Persons Who Are Deaf. Your Dedication Has Resulted in Increased Independence and Productivity By These Citizens With Disabilities. Presented by the Utah Governor's Committee on Employment of the Handicapped.

- Golden Hand Award, 1989. Presented to Beth Ann Campbell in recognition and appreciation of dedicated and meritorious service on behalf of the deaf community (This award meant the most to Beth Ann because it came from the "deaf")

- Earl Conder Award, June 28, 1990. Governor Norm Bangerter presented this award to Utah's "State Employee of the Year. 1989". She received a plaque and a $1,000 U. S. Savings Bond in recognition of going the extra mile in serving the deaf and the public. Governor Bangeter said: "Beth Ann Campbell has enhanced the cause of the deaf Community almost since childhood" (UAD Bulletin, July/August 1990).

- Kim Maibaum Lifetime Achievement Award at the UTRID banquet on August 8, 2014. Presented the award to Beth Ann Stewart Campbell for her outstanding contributions to the Utah Interpreting and Utah Deaf community. She was the "first" interpreter in many of our community's settings, paving the path for those who came after her. Because of the efforts of people like Beth Ann, we are all where we are today.

Last but not least, Beth Ann has many "firsts" under her list of accomplishments, which include:

• First Nationally Certified Professional Interpreter in Utah and the United States (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992; Emery, Davis County & Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 25, 1990).

• First hearing female to be voted as a member of the Utah Association for the Deaf Board of Directors and

• The first interpreter to develop the concept of co-therapist for interpreting for both psychiatrist and patient (Emery, Davis County, & Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 25, 1990; UAD Bulletin, July/August 1990).

Beth Ann retired after serving on the UAD Board for many years. In the April 1992 issue of the UAD Bulletin, she expressed her positive feelings about the association and its impact on the Deaf community in Utah. She developed close relationships with many board members and wished them well in their future endeavors.

After retiring, Beth Ann and Jay enjoyed escorting Deaf and hearing visitors on cruises and bus tours. They also served as full-time missionaries for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Family and Church History Mission for one year, beginning January 3, 2003. Then, they worked as missionaries at the Utah State Prison from March 2004 to July 22, 2009. To keep themselves busy, they spent their time reading, doing church work, and participating in the Utah Daughters of the Pioneers. Jay directed the "Swanee Singers" and traveled for this purpose (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

• First Nationally Certified Professional Interpreter in Utah and the United States (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992; Emery, Davis County & Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 25, 1990).

• First hearing female to be voted as a member of the Utah Association for the Deaf Board of Directors and

• The first interpreter to develop the concept of co-therapist for interpreting for both psychiatrist and patient (Emery, Davis County, & Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 25, 1990; UAD Bulletin, July/August 1990).

Beth Ann retired after serving on the UAD Board for many years. In the April 1992 issue of the UAD Bulletin, she expressed her positive feelings about the association and its impact on the Deaf community in Utah. She developed close relationships with many board members and wished them well in their future endeavors.

After retiring, Beth Ann and Jay enjoyed escorting Deaf and hearing visitors on cruises and bus tours. They also served as full-time missionaries for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Family and Church History Mission for one year, beginning January 3, 2003. Then, they worked as missionaries at the Utah State Prison from March 2004 to July 22, 2009. To keep themselves busy, they spent their time reading, doing church work, and participating in the Utah Daughters of the Pioneers. Jay directed the "Swanee Singers" and traveled for this purpose (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

It is an honor for both the Utah Deaf community and the Utah interpreting community to have Beth Ann as the first nationally certified interpreter in the state and country. Beth Ann is highly regarded for her exceptional service to the Utah Deaf community, where she worked as an interpreter and director. Her efforts have had a significant impact on the structures and services associated with the Utah Deaf community, and her dedication has greatly contributed to their continued success.

Notes

Beth Ann Campbell, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, September 18, 2012.

Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007.

Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007.

References

“Awards & Honors.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 14, no. 2/3 (July/August 1990): 11.

"Beth Ann Stewart Campbell" YouTube, October 15, 2010.

Campbell, J.J. Education of the deaf in Utah: A comprehensive study. Utah State Board of Education. Office of Administration and Institution Services. On reserve, Utah State Achieves: Series 8556, 1977.

Campbell, Jay. “Beth Ann Resigns as Director of UCCD.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 10 (March 1992): 1.

Campbell, Jay. “Beth Ann Reminisces.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 11 (April 1992): 4.

“Convention Speaker, J.J.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 8, no. 3 (June 1973): 1.

Emery, Michelle. "Campbell earns award." Ogden Standard-Examiner (July 25, 1990): p. 5.

Emery, Michell. "Campbell earns award." Davis County. (July 25, 1990, p. 13.

“Interpreters Workshop Planned.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 3, no. 3 (Spring 1964): 4.

Kinney, Valerie. “Utah Deaf Trivia.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 25.6 (November 2001): 2.

“Organization of Utah Registry of Interpreter for the Deaf.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 3 (Fall 1968): 1.

Sanderson, Robert. G. A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. March 9, 2004.

“Utah Deaf Lead Nation in Ear Research.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 9, no. 3 (June 1974): 2. “What’s in A Name?” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 9 (Spring 1963): 2.

"Beth Ann Stewart Campbell" YouTube, October 15, 2010.

Campbell, J.J. Education of the deaf in Utah: A comprehensive study. Utah State Board of Education. Office of Administration and Institution Services. On reserve, Utah State Achieves: Series 8556, 1977.

Campbell, Jay. “Beth Ann Resigns as Director of UCCD.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 10 (March 1992): 1.

Campbell, Jay. “Beth Ann Reminisces.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 11 (April 1992): 4.

“Convention Speaker, J.J.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 8, no. 3 (June 1973): 1.

Emery, Michelle. "Campbell earns award." Ogden Standard-Examiner (July 25, 1990): p. 5.

Emery, Michell. "Campbell earns award." Davis County. (July 25, 1990, p. 13.

“Interpreters Workshop Planned.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 3, no. 3 (Spring 1964): 4.

Kinney, Valerie. “Utah Deaf Trivia.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 25.6 (November 2001): 2.

“Organization of Utah Registry of Interpreter for the Deaf.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 3 (Fall 1968): 1.

Sanderson, Robert. G. A Brief History of the Origins of the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. March 9, 2004.

“Utah Deaf Lead Nation in Ear Research.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 9, no. 3 (June 1974): 2. “What’s in A Name?” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 9 (Spring 1963): 2.

Jean Greenwood Thomas

Jean Greenwood Thomas, daughter of Lucy McMills Greenwood, was an active member of the 1993 State Legislature Study Group. This group was responsible for establishing a formal interpreter training program and recognizing American Sign Language (ASL) as a foreign language in school settings. Jean's efforts also included lobbying for regulations that prevented unqualified individuals from teaching ASL in high school programs. During the 1994 Utah legislative session, Jean had network access to key members of the State Legislature Study Group, and she was a key advocate for two bills: Senate Bill 41, which certified interpreters, and Senate Bill 42, which granted ASL the same status as a foreign language. Thanks to her persistent lobbying efforts, both bills were successfully passed.

Jean Greenwood Thomas was born to Virgil Rogers Greenwood, a deaf father, and Lucy Pearl McMills, a hearing mother and the Child of a Deaf Adults (CODA). Her father attended the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) in Ogden, Utah. He left school for work in 1931, as was common for USD students at the time.

Jean's parents raised her in the Utah Deaf community. Jean also has several Deaf relatives. She had a Deaf aunt, Gloria Greenwood Barney, and a Deaf uncle, Stewart Greenwood. Ruth Felter, one of her sisters, also worked as an interpreter. Lucy had a sister, Eva, who worked as an interpreter, mostly for the Salt Lake Valley 1st Ward for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Valerie G. Kinney, a respected member of the Utah Association for the Deaf, shared that Jean's mother, Lucy, played a pivotal role in inspiring Jean's career path as an interpreter (Valerie G. Kinney, personal communication, January 9, 2013). This familial influence is a testament to the power of shared passion and dedication.

Jean's parents raised her in the Utah Deaf community. Jean also has several Deaf relatives. She had a Deaf aunt, Gloria Greenwood Barney, and a Deaf uncle, Stewart Greenwood. Ruth Felter, one of her sisters, also worked as an interpreter. Lucy had a sister, Eva, who worked as an interpreter, mostly for the Salt Lake Valley 1st Ward for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Valerie G. Kinney, a respected member of the Utah Association for the Deaf, shared that Jean's mother, Lucy, played a pivotal role in inspiring Jean's career path as an interpreter (Valerie G. Kinney, personal communication, January 9, 2013). This familial influence is a testament to the power of shared passion and dedication.

Jean taught American Sign Language (ASL) classes at Ogden High School from 1989 until 1994. In the spring of 1990, the Ogden School Board of Education and the Utah State Board of Education approved the ASL programs through the Technology Programs. From there, Jean started teaching ASL classes at Ogden High School.

While Jean was teaching ASL classes, Annette Tull, a CODA and interpreter, expressed interest in teaching ASL classes at Jordan High School. For many years, Annette and Jean interpreted for the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind. During the spring of 1993, Jean invited Cal Evans, a Jordan Special Education Director, to her high school class to see if they wanted to include ASL education in Jordan High School programs. Winefred Ospitile, who worked with the State of Utah's Vocational Education Department through the Ogden City School District, received approval from the Utah State Board of Education to provide ASL classes to complete high school credit for graduation through a vocational program. This curriculum was designed to help students become ASL interpreters. Moreover, after visiting Jean's class, Cal Evans approved Jordan High School's decision to set up ASL classes in 1994. Annette secured a teaching position at that high school with Jean's help (Jean Thomas, personal communication, October 24, 2012).

While Jean was teaching ASL classes, Annette Tull, a CODA and interpreter, expressed interest in teaching ASL classes at Jordan High School. For many years, Annette and Jean interpreted for the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind. During the spring of 1993, Jean invited Cal Evans, a Jordan Special Education Director, to her high school class to see if they wanted to include ASL education in Jordan High School programs. Winefred Ospitile, who worked with the State of Utah's Vocational Education Department through the Ogden City School District, received approval from the Utah State Board of Education to provide ASL classes to complete high school credit for graduation through a vocational program. This curriculum was designed to help students become ASL interpreters. Moreover, after visiting Jean's class, Cal Evans approved Jordan High School's decision to set up ASL classes in 1994. Annette secured a teaching position at that high school with Jean's help (Jean Thomas, personal communication, October 24, 2012).

At the same time, Jean served on the 1993 State Legislature Study Group to recognize interpreter state certification through a formal interpreter-training program and recognize American Sign Language as a foreign language in school settings. She also advocated for high school programs to have rules and regulations preventing anyone from teaching ASL without the proper credentials (Jean Thomas, personal communication, October 24, 2012). During the 1994 Utah Legislative Session, she had network access to the key members of the 1993 State Legislature Study Group. She was a major advocate for Senate Bill 41, certifying interpreters, and Senate Bill 42, granting American Sign Language the same status as a foreign language. Both bills passed as a result.

Jean highlighted how ASL classes in high schools opened the path for Salt Lake Community College (SLCC) to endorse the fully funded interpreter-training program and to give ASL high school classes recognition as a foreign language and vocational credit toward graduation. The Ogden City School District's sign language work was completed, motivating Salt Lake Community College to submit a bid for ASL interpreting at the SLCC (Jean Thomas, personal communication, October 24, 2012). The Ogden City School District's efforts and Jean's perseverance led to the completion of the majority of the work.

Jean worked with four people in authority in the Ogden City School District: Cyrus Freston, special education director with the Ogden City School District and son of Deaf parents, Cyrus and Lillian Freston; Winefred Ospitile, vocational education; Larry Leatham, assistant principal at Ogden High School; and Santiago Sandoval, principal at Ogden High School. None of this would have been possible without Jean's persistence and the cooperation of those in positions of authority.

Jean highlighted how ASL classes in high schools opened the path for Salt Lake Community College (SLCC) to endorse the fully funded interpreter-training program and to give ASL high school classes recognition as a foreign language and vocational credit toward graduation. The Ogden City School District's sign language work was completed, motivating Salt Lake Community College to submit a bid for ASL interpreting at the SLCC (Jean Thomas, personal communication, October 24, 2012). The Ogden City School District's efforts and Jean's perseverance led to the completion of the majority of the work.

Jean worked with four people in authority in the Ogden City School District: Cyrus Freston, special education director with the Ogden City School District and son of Deaf parents, Cyrus and Lillian Freston; Winefred Ospitile, vocational education; Larry Leatham, assistant principal at Ogden High School; and Santiago Sandoval, principal at Ogden High School. None of this would have been possible without Jean's persistence and the cooperation of those in positions of authority.

Dr. Lee Robinson, the superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, and Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a Deaf representative on the USDB Institutional Council, promptly hired Jean to serve as the sign language specialist after the legislation passed in the spring of 1994. She was instrumental in supporting 36 interpreters to achieve official certification (Golden Keys Award Program Book, 1999).

Jean earned the Golden Key award from the Utah State Office of Rehabilitation on October 6, 1999, for her many years of service to the Utah Deaf community. According to the 1999 Golden Key Awards program book, she demonstrated excellent leadership and dedication in the field of sign language and instruction. Jean, the daughter of a Deaf father and a CODA mother, has a clear perspective on the needs of the Utah Deaf community, particularly in terms of the skills necessary to communicate effectively in a hearing society. She has polished her skills to maximize her effectiveness in supporting others and holds the highest level of national and state interpreting certification (Golden Keys Award Program Book, 1999).

Jean earned the Golden Key award from the Utah State Office of Rehabilitation on October 6, 1999, for her many years of service to the Utah Deaf community. According to the 1999 Golden Key Awards program book, she demonstrated excellent leadership and dedication in the field of sign language and instruction. Jean, the daughter of a Deaf father and a CODA mother, has a clear perspective on the needs of the Utah Deaf community, particularly in terms of the skills necessary to communicate effectively in a hearing society. She has polished her skills to maximize her effectiveness in supporting others and holds the highest level of national and state interpreting certification (Golden Keys Award Program Book, 1999).

Furthermore, Jean is a pioneer in the field of interpretation. She was the first to teach American Sign Language as a foreign language in high school. She has served on the Utah Interpreter Certification Board. She has been a leader in sponsoring legislation regarding interpreting certification, has served on numerous committees by sharing her expertise on sign language issues, and has worked tirelessly to address Utah's Deaf population's severe shortage of qualified interpreters (Golden Keys Award Program Book, 1999).

Jean has previously won the Ogden Standard-Examiner's "Apple for the Teacher" award, as well as recognition for "Outstanding Service in Distance Education" for Utah students. She consulted the Utah State Office of Education's Department of Students at Risk Services. She remained a passionate advocate for interpreters and Deaf people's rights. Despite her full-time job and volunteer activities, she was always willing to provide her expert interpreter services whenever needed (Golden Keys Award Program Book, 1999).

Jean has previously won the Ogden Standard-Examiner's "Apple for the Teacher" award, as well as recognition for "Outstanding Service in Distance Education" for Utah students. She consulted the Utah State Office of Education's Department of Students at Risk Services. She remained a passionate advocate for interpreters and Deaf people's rights. Despite her full-time job and volunteer activities, she was always willing to provide her expert interpreter services whenever needed (Golden Keys Award Program Book, 1999).