The History of Interpreting

Services in Utah

Services in Utah

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2013

Updated in 2024

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2013

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

As a Deaf individual, I consider it a privilege to write about the history of interpreting services in Utah. I've learned a lot about the leaders that have expand state interpreting services and programs, as well as passed legislation to protect our communication accessibility needs. We are fortunate to have strong state laws that support our accessibility needs, and I hope you enjoy reading "The History of Interpreting Services in Utah" webpage as much as I do. Thank you for taking an interest in this topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Background History

of Interpreting

of Interpreting

Prior to the late 1950s and early 1960s, there were no available sign language classes or interpreter training programs. The Utah Deaf community often relied on Children of Deaf Adults (CODAs) to serve as interpreters for various events and appointments, such as meetings and church activities. Interpreters, especially CODAs, volunteered for years until the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) was established in 1964. This information was shared by Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a former Director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf and a CODA who was born and raised in Utah (Stewart, UAD Bulletin, June 1973).

During the 1960s and 1970s, marginalized communities throughout the United States fought for social equality, which led to significant changes in the interpreting industry (Humphrey & Alcorn, 2001). The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) evolved to reflect the growing importance of professional interpreters as opposed to just "helpers" in the Code of Ethics, now known as the Code of Professional Conduct (Stewart, UAD Bulletin, June 1973). In Utah, the Deaf community relied on hard of hearing individuals who learned sign language before using hearing aids, as well as those who lost their hearing but developed strong oral communication skills. However, the number of Deaf people born deaf began to increase, while the percentage of individuals who later became deaf in Utah started to decline by 1961. Additionally, the number of Deaf people with multiple disabilities also grew during this time (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1961, p. 2). As a result, the Utah Deaf community needed more interpreting services, which eventually led to the creation of the RID organization to address their interpreting needs.

During the 1960s and 1970s, marginalized communities throughout the United States fought for social equality, which led to significant changes in the interpreting industry (Humphrey & Alcorn, 2001). The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) evolved to reflect the growing importance of professional interpreters as opposed to just "helpers" in the Code of Ethics, now known as the Code of Professional Conduct (Stewart, UAD Bulletin, June 1973). In Utah, the Deaf community relied on hard of hearing individuals who learned sign language before using hearing aids, as well as those who lost their hearing but developed strong oral communication skills. However, the number of Deaf people born deaf began to increase, while the percentage of individuals who later became deaf in Utah started to decline by 1961. Additionally, the number of Deaf people with multiple disabilities also grew during this time (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1961, p. 2). As a result, the Utah Deaf community needed more interpreting services, which eventually led to the creation of the RID organization to address their interpreting needs.

The National Registry of

Interpreters for the Deaf Is Born

Interpreters for the Deaf Is Born

The National Registry of Professional Interpreters and Translators for the Deaf was established in response to various needs. The "Interpreting for the Deaf" workshop took place from June 14 to 17, 1964, at Ball State Teachers College (now Ball State University) in Muncie, Indiana. The workshop was funded by Vocational Rehabilitation as part of its ongoing program to address the issues faced by the Deaf community, and Ball State College sponsored it (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1964).

The workshop aimed to recruit and train more interpreters, establish a code of ethics, and enhance assistance and services for the Deaf community. As a result, the official non-profit interpreting organization was established on June 16, 1964 (The Silent Worker, July–August 1964). The organization later expanded its mission and scope and changed its name to the 'Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, or RID.'

Around ninety people, including one-third of Deaf individuals, attended the workshop, showing a strong commitment to the cause. Among them were many experts in deaf education, sign language, and oral communication (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1964). Their presence highlighted their dedication and passion for improving the lives of the Deaf community.

The workshop aimed to recruit and train more interpreters, establish a code of ethics, and enhance assistance and services for the Deaf community. As a result, the official non-profit interpreting organization was established on June 16, 1964 (The Silent Worker, July–August 1964). The organization later expanded its mission and scope and changed its name to the 'Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, or RID.'

Around ninety people, including one-third of Deaf individuals, attended the workshop, showing a strong commitment to the cause. Among them were many experts in deaf education, sign language, and oral communication (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1964). Their presence highlighted their dedication and passion for improving the lives of the Deaf community.

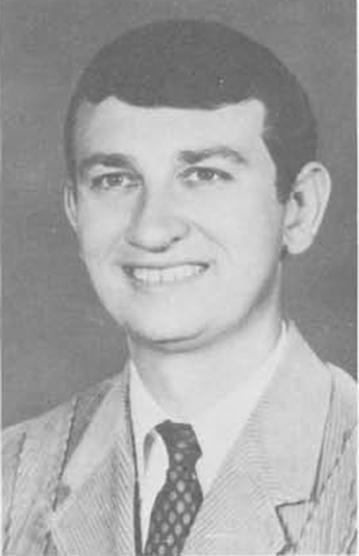

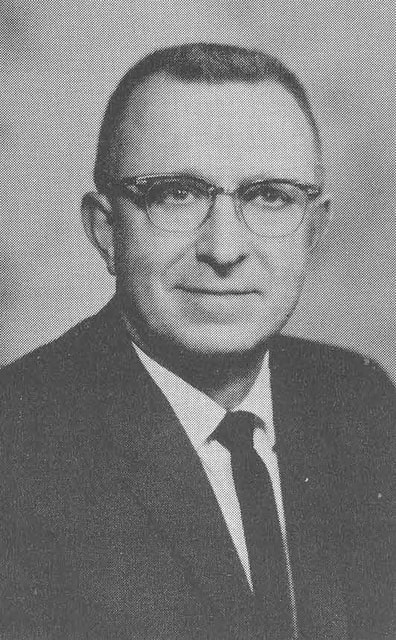

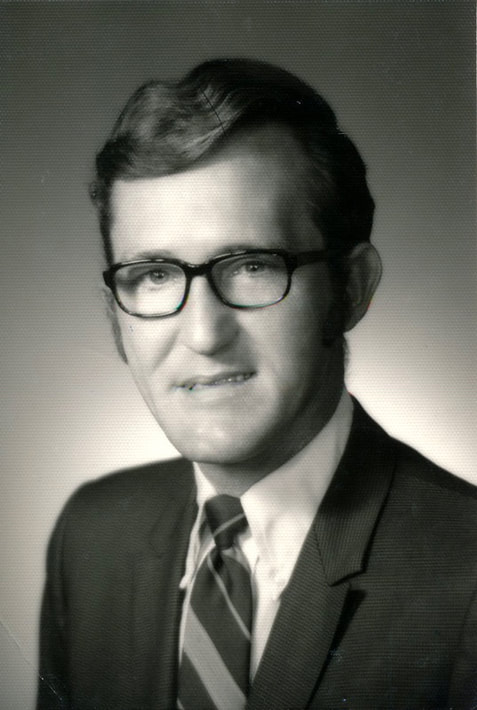

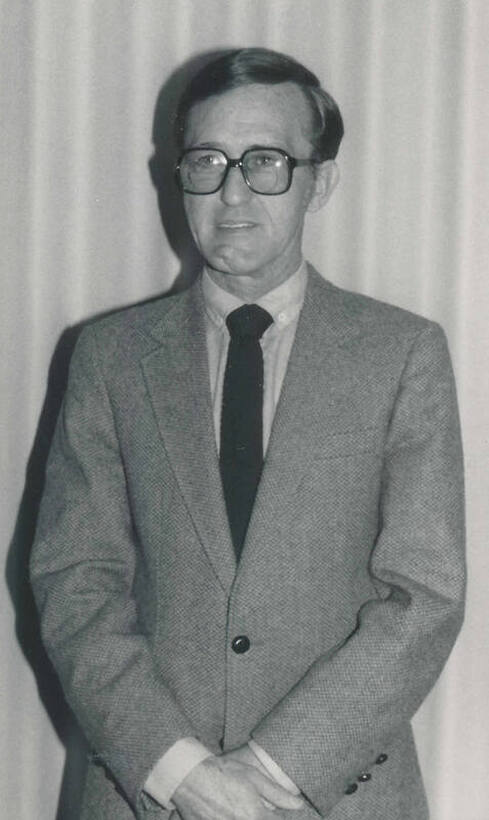

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, also known as "Sandie" and "Bob," was a prominent figure representing the Utah Association of the Deaf and the National Association of the Deaf. A month before his election as president of the National Association of the Deaf in July 1964, he demonstrated his leadership by serving as a Deaf consultant for a workshop. He soon advocated expanding interpreting services in Utah, further solidifying his influential role (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1964; Storrer, UAD Bulletin, May 2008).

Half a century ago, in 1965, the Deaf community was in dire need of a model state law that would grant them access to court proceedings. A few states had already passed laws that guaranteed Deaf individuals the right to an interpreter in court. This was a game-changer, as it meant that Deaf individuals could now enter the courtroom, protecting their lives, liberty, property, health, and daily routines. This development led to the creation of guidelines that aimed to make it easier for Deaf individuals to receive court interpreters, thereby significantly improving their daily lives (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965).

Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Holds the

Distinction of Being the First Nationally

Certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) Interpreter in Utah and the United States

Distinction of Being the First Nationally

Certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) Interpreter in Utah and the United States

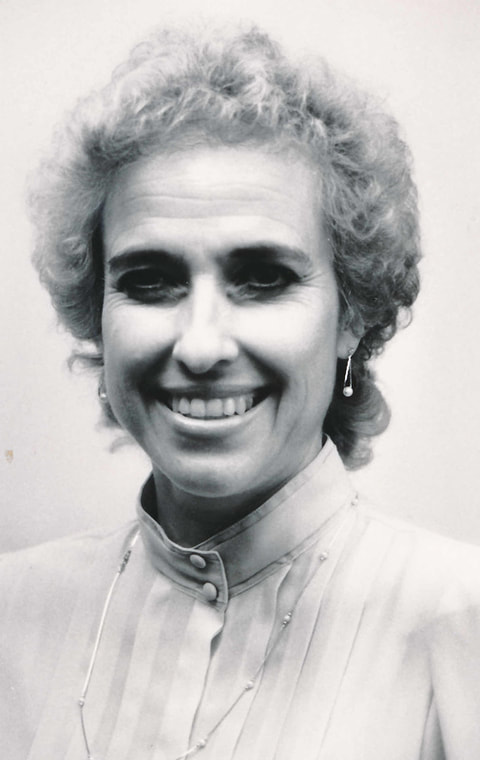

Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, the daughter of Deaf parents Arnold and Zelma Moon, has been providing interpreting services to the Deaf community in Utah since 1963. Her achievement as the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States is historically significant. Inspired by Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, president of the National Association of the Deaf and one of the first participants of the newly formed Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in 1964, Beth Ann, a Utah native and Child of Deaf Adults (CODA), took the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf certification exam. As a result, in 1965, she became the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States, a remarkable milestone that paved the way for the interpreting profession. Notably, Beth Ann obtained her first certification a year after the official recognition of the National Registry of Interpreters of the Deaf, which was founded in 1964, and six years before its incorporation in 1972. Here's her story.

In 1965, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell made history as the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States, laying the groundwork for the interpreting profession. The RID, founded in 1964, is a professional organization that promotes the profession of interpreting and transliterating American Sign Language and English. Her journey, marked by courage and determination, began in 1963 when her first husband, Wayne Stewart, a police officer, asked for her help in interpreting for a Colorado-based Deaf man who was experiencing mistreatment at the Salt Lake City Police Department. Beth Ann, feeling unsure about her skills, contacted several interpreters for assistance with interpreting. However, because they were already working, they were unavailable. One of her friends, who was an interpreter, encouraged Beth Ann to lend a hand. Despite feeling scared, Beth Ann bravely went to the police station. There, she found the Deaf man chained up and terrified. The police station left her alone with him, and soon, they were able to communicate effectively so that she could help him. Eventually, they placed him on a bus back to Colorado (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). It was her first time interpreting outside her home.

In 1965, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell made history as the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter in Utah and the United States, laying the groundwork for the interpreting profession. The RID, founded in 1964, is a professional organization that promotes the profession of interpreting and transliterating American Sign Language and English. Her journey, marked by courage and determination, began in 1963 when her first husband, Wayne Stewart, a police officer, asked for her help in interpreting for a Colorado-based Deaf man who was experiencing mistreatment at the Salt Lake City Police Department. Beth Ann, feeling unsure about her skills, contacted several interpreters for assistance with interpreting. However, because they were already working, they were unavailable. One of her friends, who was an interpreter, encouraged Beth Ann to lend a hand. Despite feeling scared, Beth Ann bravely went to the police station. There, she found the Deaf man chained up and terrified. The police station left her alone with him, and soon, they were able to communicate effectively so that she could help him. Eventually, they placed him on a bus back to Colorado (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). It was her first time interpreting outside her home.

Beth Ann's remarkable achievement of becoming the first nationally certified interpreter in 1965 also began with Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent figure in the Utah Deaf community and the president of the National Association of the Deaf from 1964 to 1968. He participated as a consultant in a workshop on 'Interpreting for the Deaf' in Muncie, Indiana, in 1964. After the workshop, he wrote a letter to Deaf parents, urging them to inform their "Child of Deaf Adults" (CODA) children about an upcoming interpreting conference (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1964). During an interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010, Beth Ann shared that her mother showed her the flyer about a conference for children of Deaf adults. They were looking to recruit and train interpreters in Utah. Her mother convinced Beth Ann, who had six children at the time, to attend the conference.

During the conference, Beth Ann witnessed an interpreter at work for the first time. Even though she had been using sign language her whole life, this experience helped her understand the difference between communication and interpreting. This event was eye-opening for her. She never thought she would one day become an interpreter. Her life changed forever when Bob Sanderson called Beth Ann, who was on the conference participant list, and asked her to interpret for him at the court. She agreed and went (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012). After this experience, Beth Ann devoted her life with unwavering commitment and passion to interpreting and advocating for the Deaf community in Utah. She has dedicated her career to working with Deaf individuals and providing interpretation services in various settings, such as the legislature, court, mental health, medical, and higher education. Beth Ann was the first interpreter at the University of Utah. She also worked full-time for the Utah Division of Rehabilitation and volunteered to interpret the evening news on television from 1971 to 1980.

During his time as NAD president, Dr. Sanderson played a significant role in motivating and supporting Beth Ann to pursue certification as an interpreter. He encouraged her to take the national certification exam at the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in Illinois in 1965. While people from various states traveled to Illinois for the exam, Beth Ann was the only one from Utah to participate (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann's achievement of becoming the first certified interpreter was not just a personal success but a significant milestone for the Deaf community and the interpreting profession. In the March 1992 UAD Bulletin, Beth Ann's second husband, Dr. Jay J. Campbell, explained that the selection and certification of interpreters were part of a nationwide training process. He went on to explain how Beth Ann became the first one to take the certification test. The program required each participant to take a test. The testing order was determined by drawing straws, which was a nerve-wracking experience. Being the first to take the test meant setting the standard for all future interpreters. During the drawing process, the woman sitting next to Beth Ann was picked first, and Beth Ann was tested last. The woman said she didn't want to be the first to take the test, and Beth Ann, understanding the significance of this opportunity and the responsibility that came with it, responded by saying she didn't want to be the last one. After exchanging numbers, Beth Ann took the test first and passed it, becoming the first nationally certified interpreter in Utah and the United States (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). Since obtaining her certification in 1965, Beth Ann has been a trailblazer in the field of interpreting. Her achievement is a testament to her courage, determination, and the respect she holds in the interpreting field. It paved the way for future interpreters and raised awareness of the importance of interpreting in the Deaf community.

Beth Ann has made significant contributions to the profession and is a strong advocate for the Utah Deaf community. Her dedication and achievements have earned her widespread respect and appreciation. Utah is fortunate to have her as the first certified interpreter in the United States. Her achievement has paved the way for many others in the field and opened doors for future interpreters. Her achievements have significantly improved the quality of life for the Deaf community, ensuring their voices were heard and understood.

During the conference, Beth Ann witnessed an interpreter at work for the first time. Even though she had been using sign language her whole life, this experience helped her understand the difference between communication and interpreting. This event was eye-opening for her. She never thought she would one day become an interpreter. Her life changed forever when Bob Sanderson called Beth Ann, who was on the conference participant list, and asked her to interpret for him at the court. She agreed and went (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012). After this experience, Beth Ann devoted her life with unwavering commitment and passion to interpreting and advocating for the Deaf community in Utah. She has dedicated her career to working with Deaf individuals and providing interpretation services in various settings, such as the legislature, court, mental health, medical, and higher education. Beth Ann was the first interpreter at the University of Utah. She also worked full-time for the Utah Division of Rehabilitation and volunteered to interpret the evening news on television from 1971 to 1980.

During his time as NAD president, Dr. Sanderson played a significant role in motivating and supporting Beth Ann to pursue certification as an interpreter. He encouraged her to take the national certification exam at the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in Illinois in 1965. While people from various states traveled to Illinois for the exam, Beth Ann was the only one from Utah to participate (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, April 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, September 18, 2012).

Beth Ann's achievement of becoming the first certified interpreter was not just a personal success but a significant milestone for the Deaf community and the interpreting profession. In the March 1992 UAD Bulletin, Beth Ann's second husband, Dr. Jay J. Campbell, explained that the selection and certification of interpreters were part of a nationwide training process. He went on to explain how Beth Ann became the first one to take the certification test. The program required each participant to take a test. The testing order was determined by drawing straws, which was a nerve-wracking experience. Being the first to take the test meant setting the standard for all future interpreters. During the drawing process, the woman sitting next to Beth Ann was picked first, and Beth Ann was tested last. The woman said she didn't want to be the first to take the test, and Beth Ann, understanding the significance of this opportunity and the responsibility that came with it, responded by saying she didn't want to be the last one. After exchanging numbers, Beth Ann took the test first and passed it, becoming the first nationally certified interpreter in Utah and the United States (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). Since obtaining her certification in 1965, Beth Ann has been a trailblazer in the field of interpreting. Her achievement is a testament to her courage, determination, and the respect she holds in the interpreting field. It paved the way for future interpreters and raised awareness of the importance of interpreting in the Deaf community.

Beth Ann has made significant contributions to the profession and is a strong advocate for the Utah Deaf community. Her dedication and achievements have earned her widespread respect and appreciation. Utah is fortunate to have her as the first certified interpreter in the United States. Her achievement has paved the way for many others in the field and opened doors for future interpreters. Her achievements have significantly improved the quality of life for the Deaf community, ensuring their voices were heard and understood.

A Workshop on Interpreting is Held

in Salt Lake City, Utah

in Salt Lake City, Utah

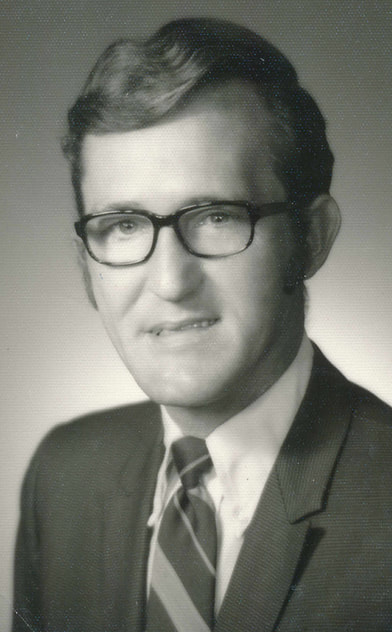

On June 3, 1967, when the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was still being developed, Robert G. Sanderson conducted a one-day training on interpreting concerns at the Ramada Inn in Salt Lake City, Utah. The Utah Division of Rehabilitation funded the program as part of its efforts to provide services to Deaf people. The program drew approximately 45 participants, including local community members, parents, teachers, and Deaf people. The morning session featured several prominent speakers, each a leader in their respective fields, including Dr. Vaughn L. Hall, administrator of the Division of Rehabilitation; Maurice Warshaw, chairman of the Utah Governor's Committee on Employment of the Handicapped; Dr. Max Cutler, a clinical psychologist; Judge Aldon J. Anderson; Robert K. Ward, statewide planning director of the Division of Rehabilitation; and Lloyd H. Perkins, President of the Salt Lake Valley Branch for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

After lunch, Bob Sanderson divided the participants into three groups, each tasked with exploring specific problems and making recommendations. Under his guidance, the session was a resounding success, with valuable insights and suggestions pouring in from all attendees. The plans that emerged from these discussions were not just ideas, but a roadmap for change. They included the establishment of a chapter of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf and a training program for interpreters, initiatives that would significantly impact the Deaf community (The UAD Bulletin, Spring-Summer, 1967).

After lunch, Bob Sanderson divided the participants into three groups, each tasked with exploring specific problems and making recommendations. Under his guidance, the session was a resounding success, with valuable insights and suggestions pouring in from all attendees. The plans that emerged from these discussions were not just ideas, but a roadmap for change. They included the establishment of a chapter of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf and a training program for interpreters, initiatives that would significantly impact the Deaf community (The UAD Bulletin, Spring-Summer, 1967).

The Establishment of the Utah Registry

of Interpreters for the Deaf

of Interpreters for the Deaf

Utah played a pioneering role in establishing the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (URID) on October 5, 1968, four years after the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was established in 1964. In its early years, URID concentrated on key activities coordinated by Robert G. Sanderson, the Coordinator of the Unit of Services for the Deaf within the Office of Rehabilitation Services. The first chapter meeting was held at the Ramada Inn in Salt Lake City, Utah, to establish a constitution, create organizational rules, and elect executives to serve on its board of directors. The meeting was a collaborative effort, sponsored jointly by the Utah Association for the Deaf and the Unit of Services for the Deaf, to bring together hearing individuals capable of interpreting and others interested in providing supportive services. The meeting also included training for competence and professional certification. This meeting marked a significant milestone in the establishment of URID and laid the groundwork for its future activities. Forty-one Deaf and hearing individuals attended the meeting, including Albert Pimentel, Executive Director of the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, who traveled from Washington, DC, to represent the organization. He described the national program and activities in the states (Davis County, September 27, 1968; The Toole Transcript, September 27, 1968; UAD Bulletin, Fall 1968).

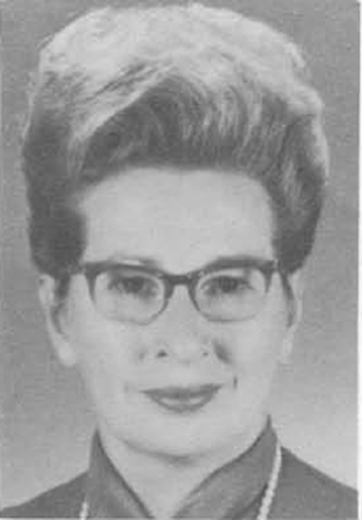

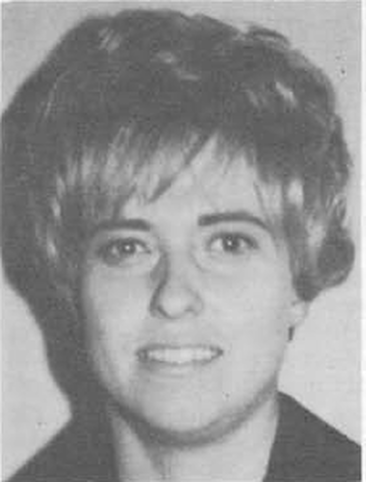

The following officers were elected to lead the URID: Gene Stewart, president; Madelaine Burton, first vice president; Edith Wheeler (Deaf), second vice president; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, secretary; Dennis Platt (Deaf), treasurer; Jonathan Freston, board member; Ned Wheeler (Deaf), six-year trustee; and Lloyd Perkins (Deaf), two-year trustee (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1968). Each of these individuals brought their unique skills and perspectives to the table, contributing to the diverse and inclusive leadership of the URID.

During the interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell shared that the interpreting community in Utah, including herself, played a pivotal role in establishing a certification process for the URID organization (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). Their shared passion and unwavering commitment brought them together, and numerous individuals selflessly dedicated their time and energy to turning this vision into a reality. The collaboration and dedication of the Utah interpreting community not only demonstrated the power of collective action but also underscored their deep commitment to the field of interpreting and the Utah Deaf community.

The following officers were elected to lead the URID: Gene Stewart, president; Madelaine Burton, first vice president; Edith Wheeler (Deaf), second vice president; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, secretary; Dennis Platt (Deaf), treasurer; Jonathan Freston, board member; Ned Wheeler (Deaf), six-year trustee; and Lloyd Perkins (Deaf), two-year trustee (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1968). Each of these individuals brought their unique skills and perspectives to the table, contributing to the diverse and inclusive leadership of the URID.

During the interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell shared that the interpreting community in Utah, including herself, played a pivotal role in establishing a certification process for the URID organization (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). Their shared passion and unwavering commitment brought them together, and numerous individuals selflessly dedicated their time and energy to turning this vision into a reality. The collaboration and dedication of the Utah interpreting community not only demonstrated the power of collective action but also underscored their deep commitment to the field of interpreting and the Utah Deaf community.

The elected officers of the

Utah Registry of Interpreters were as follows:

Utah Registry of Interpreters were as follows:

The Purpose of Utah Registry

of Interpreters for the Deaf

of Interpreters for the Deaf

The Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was established to create a reliable organization of interpreters to be used by both the Deaf community and the general public in any situation where an interpreter would be helpful. The URID aimed to establish and maintain a registry of interpreters for both sign language and oral Deaf people. Since its establishment in 1968, URID has grown to include sixteen members, most of whom were CODAs or offspring of Deaf adults. Many of them were deaf, and one was hard of hearing. Two members were married to Deaf partners. Only one hearing person learned sign language while working as a houseparent and counselor at the South Dakota School for the Deaf. While hearing individuals served as interpreters, Deaf people served as reverse interpreters, which are now known as Certified Deaf Interpreters. The individuals listed below served as either interpreters or reverse interpreters.

- Lucy McMills Greenwood (CODA & Deaf spouse)

- Dennis R. Platt (Deaf)

- Betty J. Jones (CODA)

- Madelaine P. Burton (CODA & Deaf spouse)

- Keith W. Tolzin (former houseparent and counselor at South Dakota School for the Deaf)

- Beth Ann Stewart Campbell (CODA)

- Nancy F. Murray (Deaf spouse)

- Ned C. Wheeler (Deaf)

- Iola Elizabeth Jensen (Deaf)

- Evern Lee Smith (CODA)

- Edith D. Wheeler (Hard of Hearing)

- Robert G. Sanderson (Deaf)

- Gene Stewart (CODA)

- Doris L. Wastlund (CODA)

- Lloyd H. Perkins (Deaf)

- Jon C. Freston (CODA) (UAD Bulletin, Winter 1970).

Channel 4 News Controversy

A controversy arose in 1971 when Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a staunch advocate for oral and mainstream education who believed that Deaf children needed to learn to talk to integrate into mainstream society, expressed his dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's voluntary interpreting for Channel 4 News in sign language on the right corner of the television screen, as shown in the photo below. He felt it did not align with his oral education mission. Dr. Bitter and his followers, who advocated for oral communication, complained to Dr. Avard Rigby, Robert G. Sanderson's boss, and demanded that Beth Ann not interpret the news in sign language on television. During the meeting with the oral advocates Gene Stewart, Robert Sanderson, and Beth Ann were anxiously waiting for Dr. Rigby's response. Dr. Rigby reported that Beth Ann was only on one of the three major news networks and suggested that they could change the channel if the oral advocates didn't want to see her. Dr. Rigby's response angered the oral advocates, who demanded the dismissal of Dr. Bitter's adversary, Bob Sanderson. Dr. Rigby refused, stating that Robert was one of his best employees (Robert G. Sanderson, personal communication, October 2006; Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010; Stewart, DSDHH Newsletter, April 2012, p. 3).

Bob Sanderson, an advocate of sign language, encountered difficulties in gaining credibility and recognized the significant influence of academic credentials. While battling with Dr. Bitter, he felt driven to obtain a Ph.D. to gain the credibility and respect he deserved. Robert told his coworker, Gene Stewart, that having a Ph.D. after his name would make a difference (Stewart, DSDHH Newsletter, April 2012). Dr. Bitter gained significant support due to his Ph.D., whereas Bob struggled to get the same support. Motivated by this, Bob believed that a Ph.D. would make people listen to him, especially in light of the historical animosity between these two prominent giants: Dr. Bitter, who got his Ph.D. in 1967, and Dr. Sanderson, who did not receive his Ed.D. until 1974.

Beth Ann, caught in the middle of their long-standing conflict, shared her experiences at the interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010. She revealed that every time she walked into the room, Dr. Bitter would say he didn't want her at the meeting. Bob said, "Well, she's staying." She witnessed their initial battles, with Bob 'bugging' Dr. Bitter and Dr. Bitter trying to 'bug' back. She also mentioned that during legislative hearings, Dr. Bitter would speak as fast as he could and use big words to challenge her interpreting skills. Yet Beth Ann could keep up with her interpreting job, which infuriated Dr. Bitter. Bob would sit back while Dr. Bitter tried to unsettle him by saying, 'You can read my lips.' Bob, who lost his hearing at age 11 but could speak and read lips, ignored Dr. Bitter and continued to look at Beth Ann while she interpreted. Bob refused to give in to Dr. Bitter's challenges. Beth Ann said it was a constant battle between them. She acknowledged the ongoing conflict between oral and sign language but didn't think it was as vicious as it had been during the Sanderson and Bitter era (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010).

During the political dispute between Dr. Sanderson and Dr. Bitter, Hannah P. Lewis, a hearing parent of a grown Deaf son, stated in 1977 that Dr. Sanderson has been a guiding light for the deaf all these years and emphasized the need for his continued support. She said, "I cannot thank him enough for all the help he has given my son throughout his growing-up years." "Thank God for a man like him" (Lewis, Deseret News, November 24, 1977, p. A4). His Ph.D. proved to be a valuable achievement. After completing his Ph.D., he continued to advocate for the Deaf community, leading to the naming of the Deaf Center in his honor in 2003.

Beth Ann, caught in the middle of their long-standing conflict, shared her experiences at the interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010. She revealed that every time she walked into the room, Dr. Bitter would say he didn't want her at the meeting. Bob said, "Well, she's staying." She witnessed their initial battles, with Bob 'bugging' Dr. Bitter and Dr. Bitter trying to 'bug' back. She also mentioned that during legislative hearings, Dr. Bitter would speak as fast as he could and use big words to challenge her interpreting skills. Yet Beth Ann could keep up with her interpreting job, which infuriated Dr. Bitter. Bob would sit back while Dr. Bitter tried to unsettle him by saying, 'You can read my lips.' Bob, who lost his hearing at age 11 but could speak and read lips, ignored Dr. Bitter and continued to look at Beth Ann while she interpreted. Bob refused to give in to Dr. Bitter's challenges. Beth Ann said it was a constant battle between them. She acknowledged the ongoing conflict between oral and sign language but didn't think it was as vicious as it had been during the Sanderson and Bitter era (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010).

During the political dispute between Dr. Sanderson and Dr. Bitter, Hannah P. Lewis, a hearing parent of a grown Deaf son, stated in 1977 that Dr. Sanderson has been a guiding light for the deaf all these years and emphasized the need for his continued support. She said, "I cannot thank him enough for all the help he has given my son throughout his growing-up years." "Thank God for a man like him" (Lewis, Deseret News, November 24, 1977, p. A4). His Ph.D. proved to be a valuable achievement. After completing his Ph.D., he continued to advocate for the Deaf community, leading to the naming of the Deaf Center in his honor in 2003.

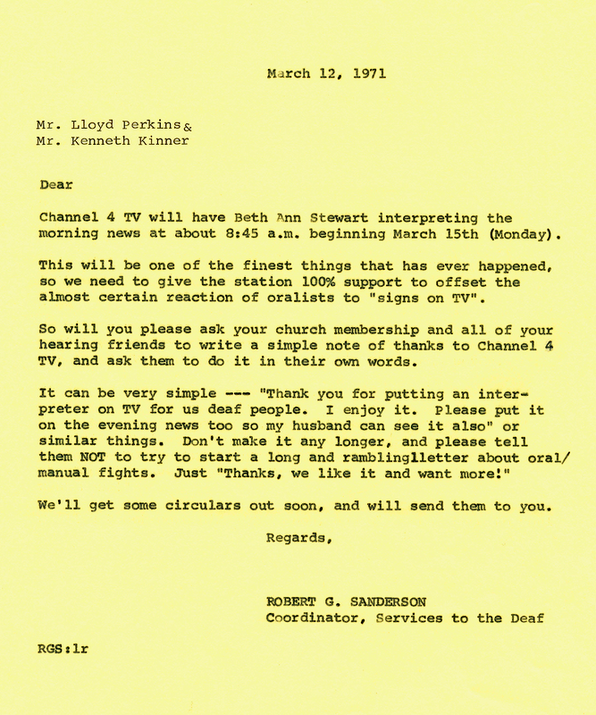

Dr. Sanderson, who was not a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, requested Lloyd Perkins, bishop of the Salt Lake Valley Ward for the Deaf, and Kenneth Kinner, branch president of the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, to ask church members to write thank-you notes to Channel 4 News for providing an interpreter on their news program during a dispute with Dr. Bitter.

From 1971 to 1980, Beth Ann volunteered as an interpreter for Channel 4 News, and the Utah Deaf community remembered seeing her on the news (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992).

From 1971 to 1980, Beth Ann volunteered as an interpreter for Channel 4 News, and the Utah Deaf community remembered seeing her on the news (Campbell, UAD Bulletin, March 1992).

The National Registry of Interpreters of the Deaf

Becomes Incorporated

Becomes Incorporated

In 1972, the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf established itself as an incorporated, officially recognized organization to uphold the standards, ethics, and professionalism of interpreters. The passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 led to an expansion of interpreting services. Nowadays, various sectors employ interpreters, including schools, colleges, universities, government organizations, hospitals, the court and legal systems, and private businesses.

A Workshop to Train

Interpreters for the Deaf

Interpreters for the Deaf

In spite of the conflict with Dr. Grant B. Bitter, the Deaf community in Utah, led by Robert G. Sanderson, expanded their interpreting service. On May 6, 1972, the Divisions of Adult Education, Training, and Vocational Rehabilitation conducted a Workshop for Training Deaf Interpreters. Esteemed speakers, including Ralph Neesam, the president of the National Registry of Deaf Interpreters; Dr. Ray L. Jones, Director of the Leadership Training Program for the Deaf at San Fernando Valley State College in Northridge, California; and Robert E. Bevill, a consumer consultant at the University of Arizona, shared their invaluable insights. The workshop aimed to enhance professionalism among oral and sign language interpreters, highlighting certification standards and procedures, evaluation methods, training experiences, fee schedules, and interpersonal relationships between deaf people and interpreters as well as interpreters themselves (UAD Bulletin, June 1972). This movement may have motivated Dr. Bitter to establish the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981. His nationwide public appearances, including workshops for oral interpreters at the University of Cincinnati and the University of Utah, have demonstrated Dr. Bitter's commitment to oral interpreting and teaching (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children...At High Risk, 1986).

Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's Observations on the National and State Registry of Deaf Interpreters and Its Impact on the Utah Deaf Community

In the June 1973 issue of the UAD Bulletin, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell discussed the role of interpreters and their profession. She hoped that the Deaf community in Utah would appreciate interpreters' responsibilities and show them respect by recognizing their duties and treating them with courtesy.

The National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) required certified interpreters to work as professionals and follow the Code of Ethics, later renamed the Code of Professional Conduct. Beth Ann Stewart Campbell noticed changes in the relationship between interpreters and members of the Utah Deaf community since the formation of the RID in 1965 and the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Utah Deaf in 1968. She observed that the interpreter's new professional status had almost turned them into machines, and they had lost their identity, thoughts, feelings, and opinions. However, Beth Ann recognized that the Utah Deaf community believed that if interpreters became unthinking and unfeeling machines, they would lose their ability to be warm, loving, and understanding people. She stressed that interpreters must remember that they are first and foremost friends of the Deaf community when not interpreting. When not working as an interpreter, interpreters should be able to accept Deaf people based on who they are and should be aware of and committed to meeting the needs of Deaf people. Before founding the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, interpreters used to volunteer their services, as Beth Ann recalled. She noted that discussing money compensation for services between the interpreter and the Deaf consumer could be sticky. She emphasized that interpreters should not accept money if it would be a hardship for the Deaf consumers who need moral assistance.

The National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) required certified interpreters to work as professionals and follow the Code of Ethics, later renamed the Code of Professional Conduct. Beth Ann Stewart Campbell noticed changes in the relationship between interpreters and members of the Utah Deaf community since the formation of the RID in 1965 and the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Utah Deaf in 1968. She observed that the interpreter's new professional status had almost turned them into machines, and they had lost their identity, thoughts, feelings, and opinions. However, Beth Ann recognized that the Utah Deaf community believed that if interpreters became unthinking and unfeeling machines, they would lose their ability to be warm, loving, and understanding people. She stressed that interpreters must remember that they are first and foremost friends of the Deaf community when not interpreting. When not working as an interpreter, interpreters should be able to accept Deaf people based on who they are and should be aware of and committed to meeting the needs of Deaf people. Before founding the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, interpreters used to volunteer their services, as Beth Ann recalled. She noted that discussing money compensation for services between the interpreter and the Deaf consumer could be sticky. She emphasized that interpreters should not accept money if it would be a hardship for the Deaf consumers who need moral assistance.

Beth Ann recommended that interpreters negotiate and agree on the fee with the Deaf consumer before providing the interpreting service. If an interpreter feels that they cannot interpret without charging a fee, they should check whether the task should be done with or without monetary compensation from the Deaf consumer. Beth Ann was concerned that collecting payment after the task was completed and the Deaf consumer thinking of the fee as excessive could destroy trust between the interpreter and the consumer. It would also be difficult for the interpreter to expect to be paid when the Deaf consumer informs them that they cannot afford to pay. Beth Ann recognized that some Deaf people took interpreters for granted and placed them on pedestals. She reminded interpreters of their opportunity to serve and the privilege of using their interpreting skills, and they should not forget the importance of their role in bridging the gap in assisting the Deaf person to communicate with the world around them.

The National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf recognized the importance of interpreters in the lives of Deaf individuals. To ensure the safety and well-being of both Deaf people and interpreters in a profession that arose to serve individuals with communication barriers, the RID created a code of ethics. RID acknowledged that, through interpreters, Deaf individuals could be granted the same right to communication as hearing individuals. Furthermore, RID recognized that the ethical standard for interpreter conduct was the same as any other profession, with a stronger emphasis on the high ethical characteristics of the interpreter's role in assisting a frequently misunderstood group of people (UAD Bulletin, November 1973). Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's discussion on the National and State Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf and its impact on the Utah Deaf community was valid, thanks to the Code of Ethics.

The National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf recognized the importance of interpreters in the lives of Deaf individuals. To ensure the safety and well-being of both Deaf people and interpreters in a profession that arose to serve individuals with communication barriers, the RID created a code of ethics. RID acknowledged that, through interpreters, Deaf individuals could be granted the same right to communication as hearing individuals. Furthermore, RID recognized that the ethical standard for interpreter conduct was the same as any other profession, with a stronger emphasis on the high ethical characteristics of the interpreter's role in assisting a frequently misunderstood group of people (UAD Bulletin, November 1973). Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's discussion on the National and State Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf and its impact on the Utah Deaf community was valid, thanks to the Code of Ethics.

Utah's First Deaf Interpreting Service

In the 1970s, the Utah Association for the Deaf received funding from United Way and used it to establish Utah's first Deaf interpreting service. This service was created to cater to the needs of the Deaf and hard of hearing communities. According to UAD Bulletin archives from June 1995, September 1996, and January 1999, this interpreting service was probably the first of its kind in the United States.

Expansion of Utah Certified Interpreters

On November 16, 1974, thirteen interpreters from Utah successfully passed the state certification exam for the Utah Registry of Interpreters. Among them were Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, Betty Jones, Madeleine Burton, and Lucy McMills Greenwood, who were renowned interpreters with local and national certifications. Additionally, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson and W. David Mortensen, who were both deaf, became the first Deaf individuals in Utah to achieve state certification as reverse interpreters (UAD Bulletin, April 1975).

The Establishment of Provo URID

The Provo Chapter of the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was established in 1975 with Emil Bussio as its first president. The roll comprised 23 members (UAD Bulletin, June 1975).

The Establishment of the

Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf

Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf

The Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf has been conducting annual training workshops since its inception in 1968. These workshops aim to provide knowledge and skills to trained interpreters, enabling them to pass state certification exams. Over the years, these workshops covered a variety of topics, including the Code of Ethics, preparation for the State Certification Examination, Reverse Interpreting, Interpreting Complexities: Role and Function of the Interpreter, The Oral Interpreter: A New Professional, and many other relevant topics (UAD Bulletin, July 1976).

The Role of Utah Association for the Deaf

In Interpreting Service

In Interpreting Service

For years, W. David Mortensen, also known as Dave, has been a friend and supporter of interpreters, continuing the work that Dr. Sanderson had started. He, as a President of the Utah Association for the Deaf, held several leadership positions that have had a significant impact on how interpreters think about and approach their work. Thanks to Dave's leadership and vision, interpreters recognized the need for high-quality interpretations and gained respect for the Utah Deaf community. The long-time interpreters were thrilled to have the opportunity to work with him. During important meetings, he patiently mentored interpreters and offered them feedback. Dave's continuous commitment to the interpretation profession and the Utah Deaf community provided interpretation training opportunities.

In 1982, as president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, Dave Mortensen was instrumental in securing funding from the Salt Lake Area Community Council for an interpreting project. With this funding, the UAD was able to hire two full-time interpreters from the Utah Community Center for the Deaf to serve the entire state. Dave's persistence and persuasive efforts laid the groundwork for professional interpreting in Utah. Despite pressure from the Salt Lake Area Community Services Council, which believed the issue to be statewide, the UAD had to abandon the interpreting project. However, Dave continued to advocate for better interpreting services, lobbying the state legislature and serving on legislative committees focused on sign language and interpreting issues (UAD Bulletin, July 2003).

The First Training Program

for Interpreters

for Interpreters

In 1983, the Utah Association for the Deaf assisted the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in developing its competent interpreter certification procedure. In partnership with this organization, the UAD developed the first interpreter training program in Utah, as well as the first testing and certification processes—another "first" in the country (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, September 1996, p. 1–3; Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, October 1999).

During the 1993 legislative session, the Utah State Legislature passed the first interpreter bill, "Interpreters for the Deaf," after lobbying by the Utah Association for the Deaf. This law acknowledges the use of qualified interpreters in legal settings, including courtrooms, doctor's offices, and hospitals. It also ensures the confidentiality of any interpreted communications (UAD Bulletin, June 1995, p. 3; Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, October 1999, p. 1 & 3; UAD Bulletin, January 2003, p. 3).

During the 1993 legislative session, the Utah State Legislature passed the first interpreter bill, "Interpreters for the Deaf," after lobbying by the Utah Association for the Deaf. This law acknowledges the use of qualified interpreters in legal settings, including courtrooms, doctor's offices, and hospitals. It also ensures the confidentiality of any interpreted communications (UAD Bulletin, June 1995, p. 3; Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, October 1999, p. 1 & 3; UAD Bulletin, January 2003, p. 3).

The Utah Interpreting Program is Formed

For years, the Utah Division of Rehabilitation supported and operated the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. In the 1980s, the Utah Division of Rehabilitation elected individuals from outside to govern the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (Stewart, UAD Bulletin, September 1990). Additionally, in 1985, members of the Utah Deaf community requested interpreting services from two different agencies. The Utah Community Center for the Deaf in Bountiful hosted the first, while Salt Lake County Mental Health in Salt Lake City hosted the second. Deaf individuals needed interpreting services for various activities such as court appearances, doctor's appointments, job interviews, and other events. At that time, they were responsible for arranging an interpreter for their appointments by calling ahead (UAD Bulletin, February 1985).

The Utah Division of Rehabilitation used to oversee the interpreter training, referral, and certification responsibilities. The Division of Services of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DSDHH) took over these responsibilities in 1990, operating out of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, later renamed the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center (Gene Stewart, UAD Bulletin, September 1990). DSDHH established the Utah Interpreting Program (UIP) in May 1992 under the supervision of Mitchel Jensen. The UIP schedules and dispatches interpreters for the Utah Deaf community (UAD Bulletin, June 1992). The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) led to the formation of several interpreting agencies, such as InterWest Interpreting Agency, ASL Communication Interpreting Agency, and Five Star Interpreting Agency, to provide interpreting services for the Utah Deaf community. The ADA has had a significant impact on interpreting services nationwide by ensuring "effective communication" and removing obstacles by providing auxiliary aids and services when necessary.

The Utah Division of Rehabilitation used to oversee the interpreter training, referral, and certification responsibilities. The Division of Services of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DSDHH) took over these responsibilities in 1990, operating out of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, later renamed the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center (Gene Stewart, UAD Bulletin, September 1990). DSDHH established the Utah Interpreting Program (UIP) in May 1992 under the supervision of Mitchel Jensen. The UIP schedules and dispatches interpreters for the Utah Deaf community (UAD Bulletin, June 1992). The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) led to the formation of several interpreting agencies, such as InterWest Interpreting Agency, ASL Communication Interpreting Agency, and Five Star Interpreting Agency, to provide interpreting services for the Utah Deaf community. The ADA has had a significant impact on interpreting services nationwide by ensuring "effective communication" and removing obstacles by providing auxiliary aids and services when necessary.

The Impact of the

Americans with Disabilities Act

Americans with Disabilities Act

In 1992, just two years after the enactment of the ADA, Utah Interpreting Services (UIS) offered Mitch Jensen, a former vocational rehabilitation counselor, the director position. This story is even more compelling because Mitch's Deaf brother, Barry, taught him American Sign Language. Mitch predicted that the ADA would have a significant impact on Utah Interpreting Services. This federal statute required doctors, lawyers, and other private and public services to pay for interpreting services (Stewart, UAD Bulletin, May 1992). Mitch's prediction came true when 19 out of 21 doctors informed him that they would no longer serve Deaf patients if an interpreter were required. In November 1992, Utah Interpreter Services, part of the state Office of Rehabilitation, informed doctors that it would no longer provide free interpreters. Under these circumstances, interpreters cost doctors and other healthcare providers between $10 and $25 per hour. According to the Salt Lake Tribune, Mitch said that 'refusal is a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act' (Wilson, The Salt Lake Tribune, December 25, 1992).

Mitch emphasized that healthcare providers are required to facilitate effective communication with patients, as mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act. If a Deaf patient requests an interpreter, the medical staff must provide one at no cost to the patient. Tamara Wharton, the ADA ombudsman for the Governor's Council for People with Disabilities, stated that refusing to serve Deaf patients is discriminatory and violates their rights. Dr. Robert H. Horne, a surgeon, argued that burdening doctors with the cost of providing interpreters is unfair. Tamara clarified that auxiliary services, including interpreters, are tax-deductible and aim to remove communication barriers and provide equal access to services for all individuals, including those with disabilities (Wilson, The Salt Lake Tribune, December 25, 1992).

Mitch emphasized that healthcare providers are required to facilitate effective communication with patients, as mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act. If a Deaf patient requests an interpreter, the medical staff must provide one at no cost to the patient. Tamara Wharton, the ADA ombudsman for the Governor's Council for People with Disabilities, stated that refusing to serve Deaf patients is discriminatory and violates their rights. Dr. Robert H. Horne, a surgeon, argued that burdening doctors with the cost of providing interpreters is unfair. Tamara clarified that auxiliary services, including interpreters, are tax-deductible and aim to remove communication barriers and provide equal access to services for all individuals, including those with disabilities (Wilson, The Salt Lake Tribune, December 25, 1992).

Questions from the Utah Deaf Community on the Americans with Disabilities Act

In February 1993, doctors refused to pay for interpreting services in Utah, causing confusion and concern among members of the Deaf community. They began to question the influence of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in their personal lives and wondered if it could benefit them. They also asked how they could make the ADA work for them. In response to these concerns, Mitch Jensen, Director of the Utah Interpreter Service, clarified that the ADA had far-reaching implications that could offer the same opportunities to Deaf individuals as those provided to hearing individuals. He listed these implications in the February 1993 issue of the UAD Bulletin, and they were as follows:

Mitch informed the Utah Deaf community that doctors and lawyers were unwilling to pay for interpreting services. As a result, the Utah Interpreter Program contacted all doctors and lawyers and informed them that the ADA required them to provide an interpreter for a Deaf individual attending their appointments. Despite opposition from some, Mitch hoped that over time, many would comprehend this law and provide the necessary communication that members of the Utah Deaf community deserve. Additionally, he underlined that the ADA process would only work if the Utah Deaf community engaged and informed others about their needs and requirements (UAD Bulletin, February 1993).

In April 1993, Mitch began to see how the ADA was taking effect. More businesses and public places provided interpreters for Deaf people who requested them, and the number of calls from Deaf people decreased. Conversely, those who needed interpreters for Deaf people were making more calls. In Mitch's view, this is how the ADA works best: by shifting the burden of finding and providing interpreters from the deaf to the hearing (Jensen, DSDHH Newsletter, April 1993).

- It allows you to attend classes that you would have otherwise been unable to attend because no interpreter was available.

- It allows you to see your doctor, dentist, and lawyer and communicate in the same way that hearing people do, using an interpreter or other assistive aids.

- It allows you to participate in a legislative process you may have previously been exempt from because you were unable to communicate with those involved.

- It allows you to serve on jury duty and have the same opportunities that hearing individuals have.

Mitch informed the Utah Deaf community that doctors and lawyers were unwilling to pay for interpreting services. As a result, the Utah Interpreter Program contacted all doctors and lawyers and informed them that the ADA required them to provide an interpreter for a Deaf individual attending their appointments. Despite opposition from some, Mitch hoped that over time, many would comprehend this law and provide the necessary communication that members of the Utah Deaf community deserve. Additionally, he underlined that the ADA process would only work if the Utah Deaf community engaged and informed others about their needs and requirements (UAD Bulletin, February 1993).

In April 1993, Mitch began to see how the ADA was taking effect. More businesses and public places provided interpreters for Deaf people who requested them, and the number of calls from Deaf people decreased. Conversely, those who needed interpreters for Deaf people were making more calls. In Mitch's view, this is how the ADA works best: by shifting the burden of finding and providing interpreters from the deaf to the hearing (Jensen, DSDHH Newsletter, April 1993).

The Establishment of the

Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf

Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf

On September 26, 1992, a special meeting was held to establish a new affiliate, the Utah State Chapter of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (UTRID), at the Utah Community Center for the Deaf. This establishment followed the closure of the previous Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (URID) for unclear reasons. The primary mission of UTRID was to unite the Utah interpreter community, professionalize the interpretation field, and strengthen ties between interpreters and the Utah Deaf community. The first board of directors of UTRID was led by President Chris Wakeland, Vice President Catherine Spaulding, Secretary Alli Robertson, Treasurer Jennifer Forsgren, SLC Region Representative Annette Tull, and Provo Region Representative Dan Parvz (Wakeland, UAD Bulletin, November 1992).

The Enactment of

Senate Bill 41 and 42

Senate Bill 41 and 42

During the 1994 Utah State Legislative session, the Utah Association for the Deaf and the Utah interpreting community dedicated extensive time and effort to advocate and lobby lawmakers to pass House Bill (HB) 161. The bill, sponsored by Mel Brown, was successfully passed during that session. This bill established the State Legislature Task Force, which was responsible for assessing the state's interpreting service needs, a significant milestone in Utah's history of interpreting services.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, an ASL interpreter and instructor and the daughter of a well-known interpreter, Lucy McMills Greenwood, was a member of the task force. Her contributions to developing a formal interpreter training program and advocacy for recognizing American Sign Language (ASL) as a foreign language in schools were instrumental (Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, October 24, 2012). Kristi Mortensen, a Deaf Education Advocate and daughter of UAD President W. David Mortensen, was also a member of the task force (Mortensen-Nelson, UAD Bulletin, April 1994).

Jean Greenwood Thomas, an ASL interpreter and instructor and the daughter of a well-known interpreter, Lucy McMills Greenwood, was a member of the task force. Her contributions to developing a formal interpreter training program and advocacy for recognizing American Sign Language (ASL) as a foreign language in schools were instrumental (Jean Greenwood Thomas, personal communication, October 24, 2012). Kristi Mortensen, a Deaf Education Advocate and daughter of UAD President W. David Mortensen, was also a member of the task force (Mortensen-Nelson, UAD Bulletin, April 1994).

The task force focused on the following areas:

- Certification, enforcement, and definition of a qualified interpreter.

- They established minimum standards for interpreters to work in various settings such as Utah's elementary, high school, postsecondary school, community interpreting, and legal and medical situations.

- Additionally, the team was responsible for recruiting qualified interpreters and providing them with proper training.

- One of their initiatives included teaching American Sign Language as a foreign language in Utah, as reported in Jensen's article in the DSDHH Newsletter in May 1993.

In 1994, after a year of interpreting task force meetings, the Utah legislature passed two bills: Senate Bill (SB) 41 and SB 42. These bills addressed interpreter certification issues and the recognition of American Sign Language (ASL) in schools.

The Utah Association for the Deaf successfully sponsored SB 41, a bill that focused on interpreter certification and training. The state of Utah funded the bill, and it became an official part of the curriculum at Salt Lake Community College. Dave Mortensen, the president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, and Annette Tull, an instructor in the Salt Lake Community College Interpreter Training Program, worked tirelessly to ensure the bill's passage through the legislative process. At the same time, SB 42 recognized ASL as a foreign language in secondary and post-secondary schools, which was a crucial step toward promoting ASL and Deaf culture in secondary and postsecondary schools. Despite its narrow passage through the Senate, SB 41 has had a significant impact on promoting interpreting services to address communication accessibility needs for Deaf people since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, in 1990 (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, February 1994; Kinney, UAD Bulletin, April 1994). Without Dave and Annette, Salt Lake Community College's Interpreter Training Program would not exist. Under the law, interpreting agencies are required to train, provide, and promote competent interpreters for Deaf and hard of hearing individuals. Dave's contributions left a significant legacy that 'encouraged interpreters to pursue professional development' (UAD Bulletin, July 2003). Jean Greenwood Thomas and Kristi Mortensen also played a crucial role in behind-the-scenes advocacy for the approval of SB 41 and SB 42 with the 1993 State Legislature Study Group. As a result, Utah was the first state to establish legislation requiring licensed interpreters. All these efforts significantly improved the lives of the Deaf community in Utah.

According to View Magazine in 2015, Utah was the first state in the United States to pass a law requiring state certification for all interpreters. While the rest of the states did not have their own state certification requirement law, except to comply with the RID guidelines (Schafer, Views, Fall 2014–Winter/Spring 2015), This was an essential step in ensuring that the Utah Deaf community had access to high-quality interpreting services delivered by highly qualified interpreters. Utah is fortunate to have highly qualified and professional interpreters who can provide excellent service to the Deaf community.

The Utah Association for the Deaf successfully sponsored SB 41, a bill that focused on interpreter certification and training. The state of Utah funded the bill, and it became an official part of the curriculum at Salt Lake Community College. Dave Mortensen, the president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, and Annette Tull, an instructor in the Salt Lake Community College Interpreter Training Program, worked tirelessly to ensure the bill's passage through the legislative process. At the same time, SB 42 recognized ASL as a foreign language in secondary and post-secondary schools, which was a crucial step toward promoting ASL and Deaf culture in secondary and postsecondary schools. Despite its narrow passage through the Senate, SB 41 has had a significant impact on promoting interpreting services to address communication accessibility needs for Deaf people since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, in 1990 (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, February 1994; Kinney, UAD Bulletin, April 1994). Without Dave and Annette, Salt Lake Community College's Interpreter Training Program would not exist. Under the law, interpreting agencies are required to train, provide, and promote competent interpreters for Deaf and hard of hearing individuals. Dave's contributions left a significant legacy that 'encouraged interpreters to pursue professional development' (UAD Bulletin, July 2003). Jean Greenwood Thomas and Kristi Mortensen also played a crucial role in behind-the-scenes advocacy for the approval of SB 41 and SB 42 with the 1993 State Legislature Study Group. As a result, Utah was the first state to establish legislation requiring licensed interpreters. All these efforts significantly improved the lives of the Deaf community in Utah.

According to View Magazine in 2015, Utah was the first state in the United States to pass a law requiring state certification for all interpreters. While the rest of the states did not have their own state certification requirement law, except to comply with the RID guidelines (Schafer, Views, Fall 2014–Winter/Spring 2015), This was an essential step in ensuring that the Utah Deaf community had access to high-quality interpreting services delivered by highly qualified interpreters. Utah is fortunate to have highly qualified and professional interpreters who can provide excellent service to the Deaf community.

W. David Mortensen Contributes

to the Expansion of Interpreting Services

to the Expansion of Interpreting Services

Dave Mortensen, the devoted president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, lobbied the Utah State Legislature to recognize American Sign Language as a language through Senate Bill 42 in 1994. This bill legitimized the use of American Sign Language in various contexts. Dave also played an important role in creating the Interpreter Training Program at Salt Lake Community College. He started this process by speaking with committees at the Salt Lake City Community Councils and the United Way of Salt Lake City, advocating for a comprehensive interpreter training program. His efforts resulted in the creation of the UAD's interpreter service, which could schedule appointments for doctors, meetings with lawyers, and other events. The Utah Community Center for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, now known as the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center, housed the Utah Interpreter Program under Mitchel Jensen's direction.

Thanks to Dave's efforts, several schools and universities in Utah expanded their interpreting training programs, and many freelance interpreting agencies also grew. Additionally, Dave's reminders to the medical community about providing sign language interpreters for their Deaf patients and clients have made more medical professionals aware of the need for such services (UAD Bulletin, October 2007). His personal dedication to interpreting has dramatically improved the lives of the Deaf community in Utah.

Thanks to Dave's efforts, several schools and universities in Utah expanded their interpreting training programs, and many freelance interpreting agencies also grew. Additionally, Dave's reminders to the medical community about providing sign language interpreters for their Deaf patients and clients have made more medical professionals aware of the need for such services (UAD Bulletin, October 2007). His personal dedication to interpreting has dramatically improved the lives of the Deaf community in Utah.

The First Certified

Deaf Interpreter in Utah

Deaf Interpreter in Utah

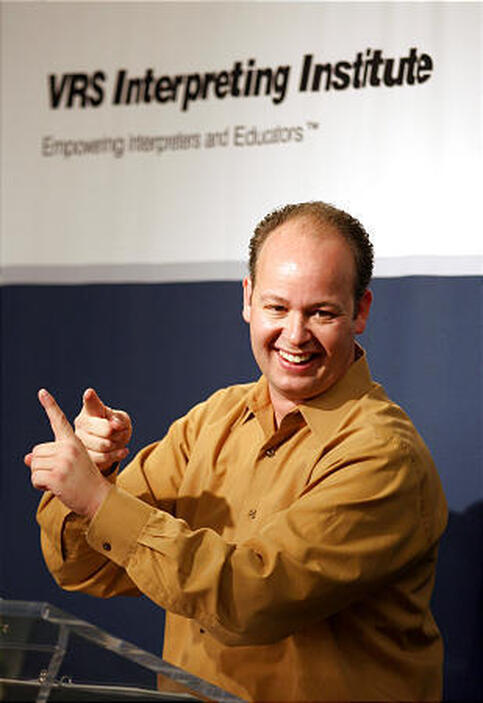

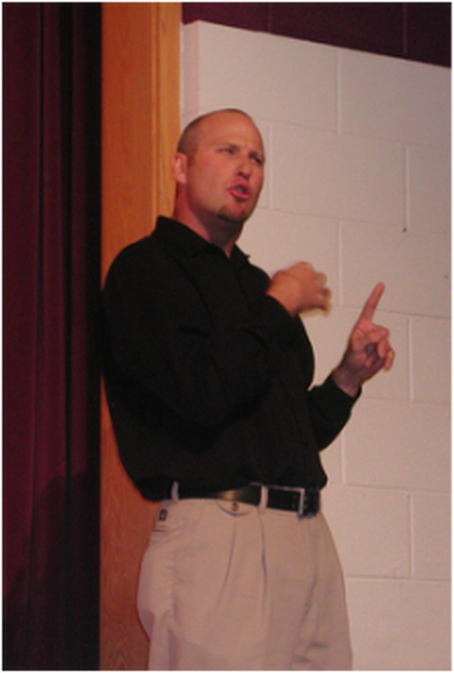

Certified Deaf Interpreters (CDIs) are individuals who have earned a nationally recognized certification and are either deaf or hard of hearing. In 2006, Trenton Marsh became the first Utah Deaf person to receive CDI certification, which is a testament to the rigorous standards of this national certification. His training to become a CDI took place at the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

HB 371 Would Penalize ASL Interpreters

Working Without Certification

Working Without Certification

In 2013, the Utah interpreting community requested changes to the state's interpreter law, called Senate Bill (SB) 41. This law had several loopholes that allowed hospitals to avoid using certified interpreters by instructing Deaf individuals to bring in a signer. Consequently, this left many members of the Utah Deaf community without legal protection for years. In response to this issue, the state introduced House Bill (HB) 371 to penalize individuals lacking state certification as interpreters trained in American Sign Language. The purpose of this bill was to ensure the use of qualified interpreters when requested (Leonard, KSL.com, March 2, 2013). Mitch Jensen, Director of the Utah Interpreter Program, explained that HB 371 would close loopholes and give DSDHH the authority to enforce the law (Mitch Jensen, personal communication, March 11, 2013). Dale Boam, a former professor of Deaf Studies at Utah Valley University, an attorney, and an experienced ASL interpreter, stated that many individuals had been performing the task without proper certification, essentially taking advantage of Deaf people. He believed enforcing the law would help ensure quality for the Utah Deaf community (Leonard, KSL.com, March 2, 2013).

Representative Ronda Menlove, the bill's sponsor, recognized the importance of having the appropriate official sign the bill (Leonard, KSL.com, March 2, 2013). She is married to Dr. Martell Menlove, the state superintendent of public instruction, who was involved in a dispute between Steven Noyce, the superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, and the Utah Deaf Education Core Group. This dispute, which centers around the ASL/English bilingual safeguarded by the Core Group and Listening and Spoken Language that then-Superintendent Noyce advocated for, is of significant importance. For more information on this topic, visit the "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream" webpage. It's worth noting that Representative Menlove is also the grandmother of a Deaf child. Her daughter, Sara Menlove Doutre, was the President of the Utah Hands and Voices Chapter.

On March 13, 2013, the Utah legislature passed HB 371, which granted the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community more protection by requiring medical professionals to hire certified sign language interpreters. However, some doctors opposed the bill and wanted to change the law so they wouldn't have to hire interpreters. Mitch Jensen, Director of the Utah Interpreter Program, said some doctors came to Capitol Hill and asked Senator Aaron Osmond to change the law so medical professionals wouldn't have to hire certified sign language interpreters (Mitch Jensen, personal communication, March 14, 2013). Despite this opposition, Representative Menlove insisted that the bill pass as drafted (Leonard, KSL.com, March 2, 2013). Marilyn Call, the Director of the Division of Services of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, spent many hours persuading lawmakers to support the bill. Ultimately, the legislature passed HB 371, giving the DSDHH the authority to enforce the law and protect Utah's Deaf community (Mitch Jensen, personal communication, March 14, 2013).

The First Utah

Certified Deaf Interpreter

Certified Deaf Interpreter

In an effort to improve the interpreter certification process, Trenton Marsh, who replaced retired Mitch Jensen as the Utah Interpreter Program Manager, introduced three types of interpreter certifications: Novice, Professional, and the Utah CDI certification. Later in the fall of 2019, Marsh introduced the Utah Certified Deaf Interpreter (UCDI) certification, which includes two parts: a performance exam and a knowledge exam. Adam Janisieski, who is deaf, became the first person to pass both the performance and knowledge exams, earning the Utah Certified Deaf Interpreter certification in Utah on July 20, 2021.

The Expansion of the

Interpreter Training Programs

Interpreter Training Programs

Interpreting services are in high demand, and interpreter training programs have become increasingly popular. The DSDHH Utah Interpreter Program, Salt Lake Community College, Utah Valley University, and Utah State University offer formal training for anyone interested in pursuing a career in interpreting.

Compared to other states, Utah sets the standard for interpreting services and has a well-structured interpreting system, thanks to Utah law. This has resulted in excellent interpreting services that meet the communication accessibility needs of Deaf or hard of hearing individuals. We are grateful to the many pioneers who have contributed to the development and expansion of interpreting services in Utah!

A Videotape of Beth Ann Campbell

in the Interpreter In-Service Training

at Salt Lake Community College,

October 15, 2010

in the Interpreter In-Service Training

at Salt Lake Community College,

October 15, 2010

Hosted by Julie Hesterman Smith,

the SLCC Interpreter Service Manager

the SLCC Interpreter Service Manager

During our interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a family friend of my colleague Julie Hesterman Smith, who is the Interpreter Manager of the SLCC's Accessibility and Disability Services, shared valuable insights. Beth Ann, a Child of Deaf Adults (CODA), grew up in a Deaf family, which gave her a strong understanding of sign language, leading her to become the first nationally certified Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) interpreter. Her experiences as the director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, as well as her insights into the origins of the ASL interpreting profession, were incredibly important. Having her share her journey and perspective with us was a privilege.

We are very grateful to Beth Ann for her inspiring advocacy for the Utah Deaf community. Her experiences as an interpreter during the pre-Americans with Disabilities Act era, her firsthand experience with the deaf education battles during the Bitter/Sanderson era, and her continued advocacy were truly enlightening. Unfortunately, I was unable to attend her workshop due to personal reasons. I want to express my heartfelt thanks to Julie Hesterman Smith, my co-worker, for making Beth Ann's presentation accessible to me.

Finally, Beth Ann's insights into the interpreting world were invaluable. It was a privilege to have her share her journey and perspective. Getting to know her in person was also a privilege and an honor. We recommend activating captions while watching the video recording of her presentation.

Thank you, Beth Ann, for interpreting and advocating for our causes!

Jodi Becker Kinner

We are very grateful to Beth Ann for her inspiring advocacy for the Utah Deaf community. Her experiences as an interpreter during the pre-Americans with Disabilities Act era, her firsthand experience with the deaf education battles during the Bitter/Sanderson era, and her continued advocacy were truly enlightening. Unfortunately, I was unable to attend her workshop due to personal reasons. I want to express my heartfelt thanks to Julie Hesterman Smith, my co-worker, for making Beth Ann's presentation accessible to me.

Finally, Beth Ann's insights into the interpreting world were invaluable. It was a privilege to have her share her journey and perspective. Getting to know her in person was also a privilege and an honor. We recommend activating captions while watching the video recording of her presentation.

Thank you, Beth Ann, for interpreting and advocating for our causes!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Notes

Beth Ann Campbell, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, September 18, 2012.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, October 24, 2012.

Mitch Jensen, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, March 11, 2013.

Mitch Jensen, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, March 14, 2013.

Robert G. Sanderson, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, October 2006.

Valerie G. Kinney, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, November 4, 2013.

Jean Greenwood Thomas, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, October 24, 2012.

Mitch Jensen, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, March 11, 2013.

Mitch Jensen, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, March 14, 2013.