The Impact of the Oral Leaders

Within and Outside of Utah

Complied & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney & Bronwyn O’Hara

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney & Bronwyn O’Hara

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Author’s Note

As a parent of two Deaf children, my passion for deaf education comes from my personal journey. My father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, also sparked my interest and shared with me the history of deaf education in Utah, including its oral and mainstreaming impact. This inspired me to meticulously document the controversial events of that era. If it weren't for him, I wouldn't be able to advocate for my kids without knowing the history. My studies at the Gallaudet School Social Work Program further deepened my understanding of the complexities of education, legislation, and policy. Moreover, my role on the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind has truly empowered me to advocate for my children and others in Utah who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled. This platform has given me the strength and voice to make a difference.

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

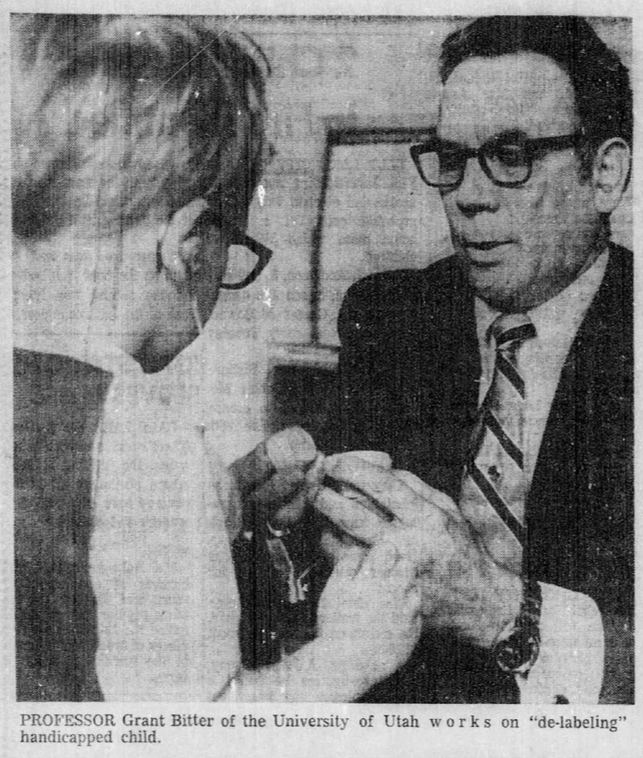

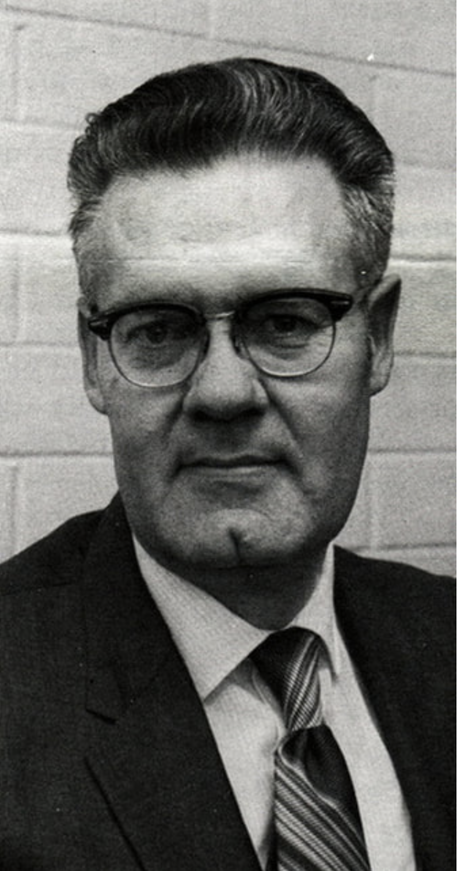

As someone deeply committed to advocating for ASL/English bilingual education in Utah, I have witnessed firsthand the tremendous impact of a growing oral education environment and the role of steadfast oral advocates, particularly Steven W. Noyce, Superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, as well as others with Dr. Grant B. Bitter and Dr. Karl R. White. It had become increasingly clear that change was necessary to provide an equal deaf educational system in ASL/English bilingual and listening and spoken language. In the Deaf community, we have been grappling with the influence of three prominent oral advocates—Dr. Grant B. Bitter, Steven W. Noyce, and Dr. Karl R. White—in our backyard, who have wielded significant power over deaf education, both within the state and nation, as explained on this webpage.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

As someone deeply committed to advocating for ASL/English bilingual education in Utah, I have witnessed firsthand the tremendous impact of a growing oral education environment and the role of steadfast oral advocates, particularly Steven W. Noyce, Superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, as well as others with Dr. Grant B. Bitter and Dr. Karl R. White. It had become increasingly clear that change was necessary to provide an equal deaf educational system in ASL/English bilingual and listening and spoken language. In the Deaf community, we have been grappling with the influence of three prominent oral advocates—Dr. Grant B. Bitter, Steven W. Noyce, and Dr. Karl R. White—in our backyard, who have wielded significant power over deaf education, both within the state and nation, as explained on this webpage.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Acknowledgment

When Steven W. Noyce became superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind in 2009, his support for oral and mainstream education raised concerns within the Utah Deaf community. As a parent of Deaf children, I was worried that Steven Noyce would carry Dr. Grant B. Bitter's legacy by promoting oral education and mainstreaming all Deaf children in Utah. On November 3, 2009, I raised this issue with him and Associate Superintendent Jennifer Howell. I knew that Steven, a former student of Dr. Bitter's Oral Training Program at the University of Utah and a long-time employee at the Utah School for the Deaf, was fully aware of the controversy between oral and sign language. To protect the ASL/English bilingual program, I detailed Dr. Grant B. Bitter's controversial history of oral and mainstreaming advocacy, as well as the profound impact of the dual-track and two-track programs at the Utah School for the Deaf. I recommended providing an equal balance between the Listening and Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual options for families of Deaf children. I also requested preventive measures to avoid the recurrence of similar issues. Steven acknowledged the accuracy of the information and said, "This is the most accurate paper I have ever read." This recognition of the paper's credibility underscores the importance of our advocacy efforts. I owe a debt of gratitude to my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, for sharing this critical history with me. His insights and knowledge have proven invaluable in our advocacy efforts for deaf education. Without his help, we couldn't have opposed the oral agenda.

Thank you, Ken!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Thank you, Ken!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Impact of

the Utah Oral Leaders

the Utah Oral Leaders

Over the years, the Utah Deaf community has shown incredible resilience in the face of opposition from three prominent oral advocates in Utah: Dr. Grant B. Bitter, Steven W. Noyce, and Dr. Karl R. White. The Utah Oral Advocates for Listening and Spoken Language (LSL-replaced oral) consistently praised the Utah School for the Deaf as a national model. They highlight the school's provision of both listening & spoken language and ASL/English bilingual (replaced total communication) programs, known as the dual-track program (1960s) and two-track program (1970s), as well as the school's outreach services to promote mainstreaming efforts. However, the Utah Deaf community, under the leadership of the Utah Deaf Education Core Group, recognized the ineffectiveness of this system and actively advocated for and safeguarded the ASL/English bilingual program.

Superintendent Noyce proposed the two-track program as a model for other state schools for the deaf nationwide in an article titled "Schools for the Deaf Grapple with Balancing Two Tracks," which was published in The Salt Lake Tribune on February 21, 2011. The program aimed at offering the Listening & Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual tracks to empower parents to make choices for their Deaf children. However, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group, a group of concerned parents and members of the Utah Deaf community, saw this as an attempt to decrease the ASL/English bilingual Program and steer more Deaf and hard of hearing children into the LSL Program. This situation was a cause for concern, as other state schools, such as the South Dakota School for the Deaf, the Delaware School for the Deaf, and the Indiana School for the Deaf, also faced the threat of losing their ASL/English bilingual programs due to similar issues.

Superintendent Noyce proposed the two-track program as a model for other state schools for the deaf nationwide in an article titled "Schools for the Deaf Grapple with Balancing Two Tracks," which was published in The Salt Lake Tribune on February 21, 2011. The program aimed at offering the Listening & Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual tracks to empower parents to make choices for their Deaf children. However, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group, a group of concerned parents and members of the Utah Deaf community, saw this as an attempt to decrease the ASL/English bilingual Program and steer more Deaf and hard of hearing children into the LSL Program. This situation was a cause for concern, as other state schools, such as the South Dakota School for the Deaf, the Delaware School for the Deaf, and the Indiana School for the Deaf, also faced the threat of losing their ASL/English bilingual programs due to similar issues.

On June 6, 2011, Timothy Chevalier, a former ASL/English Bilingual Specialist, shared that the South Dakota School for the Deaf was likely the first state school to copy the Utah School for the Deaf's two-track program and its outreach services model in 2005 after visiting and consulting with them. The two-track program, as applied at SDSD, divided students into Listening and Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual programs. The school prohibited LSL students with cochlear implants from interacting with students in the ASL/English bilingual program at any time, including recess and lunch. The school also avoided exposing the LSL students to sign language (Timothy Chevalier, personal communication, June 6, 2011).

To promote mainstreaming, the administration of SDSD has also collaborated with public schools to revise their practices to integrate LSL students who are Deaf and hard of hearing into the LSL Program with non-deaf students in public schools. The goal was to help these students learn to listen and speak more effectively. In 2007, some South Dakota families who were supporters of ASL opposed the new system, but their efforts were unsuccessful. Consequently, they had to make the difficult decision to move out of the state to enroll their Deaf children in other state schools for the deaf. By 2009, the South Dakota School for the Deaf no longer existed as a school. Instead, it provided outreach services to students in the public school system (Timothy Chevalier, personal communication, June 6, 2011).

Two More State Schools for the Deaf

Impacted by the Oralism Movement

Impacted by the Oralism Movement

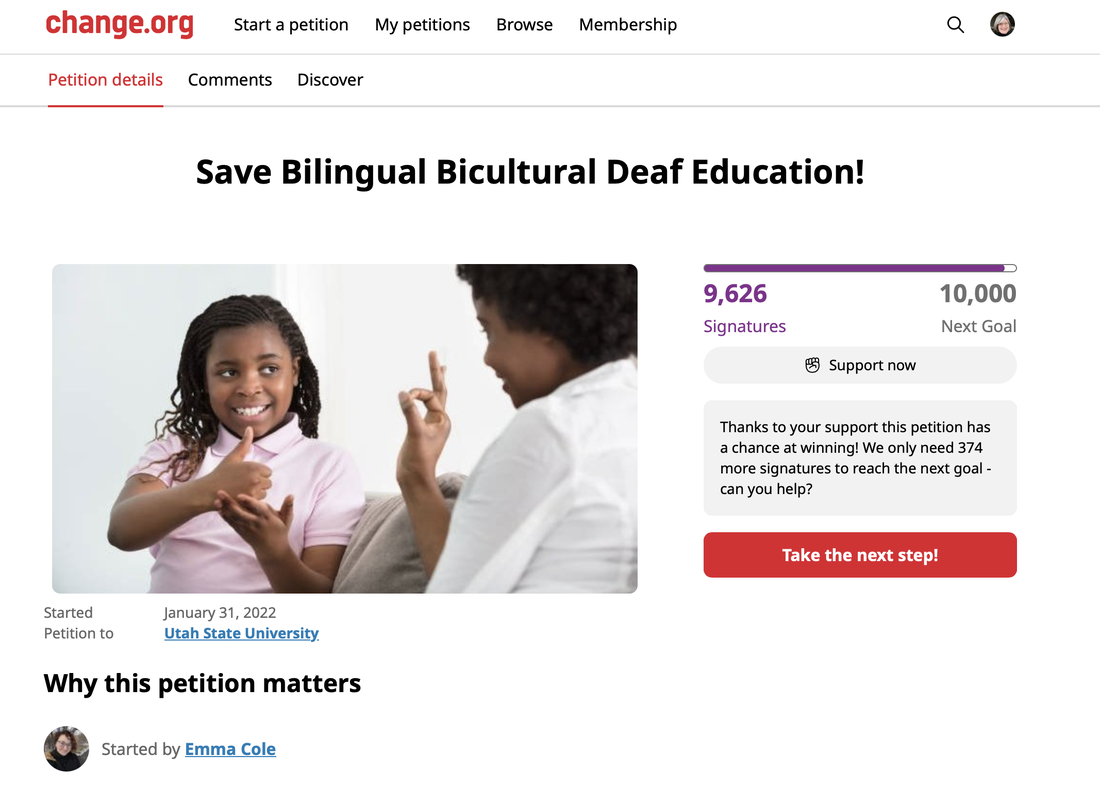

This situation was not unique to the South Dakota School for the Deaf. Theresa Bulger also led the Oral Only Option Schools Group (OOOS) in an attempt to replicate the Utah School for the Deaf's two-track model and its outreach services. The Alexander Graham Bell Association supported their efforts and actively promoted the LSL option in several states. In 2010, Dr. Karl R. White, a prominent Utah LSL program advocate, testified before the California Legislature to advocate for AD 2072 passage. Despite Dr. White's efforts, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed the bill in response to a significant outcry from the California Deaf community.

Like the South Dakota School for the Deaf, in 2011, Delaware and Indiana also worked to make Listening & Spoken language (LSL) a legal option for Deaf children in their state schools for the deaf. Indiana succeeded in their mission. Superintendent Noyce enthusiastically shared at the Utah State Office of Education's Deaf National Agenda Committee meeting that Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels sought his advice on implementing the two-track program and outreach services provided by the Utah School for the Deaf during the Indiana Deaf community's protest. Superintendent Noyce further stated that the Illinois School for the Deaf and the New Jersey School for the Deaf will follow in the footsteps of the Indiana School for the Deaf by adopting the Utah School for the Deaf's delivery services model (Steven W. Noyce, personal communication, March 12, 2010). On top of that, the Delaware School for the Deaf, which provides bilingual education in American Sign Language and English, was pressured to offer the LSL option by the LSL-promoting CHOICES Delaware organization, created in 2009. Fortunately, on September 10, 2010, Delaware Governor Jack Markell signed House Bill 283, the Delaware Hard of Hearing Children's Bill of Rights, into law to safeguard ASL/English bilingual education. Texas, Colorado, and California have also implemented similar legislation (www.christina.k12.de.us/DSPDHH/DHHBillofRights.htm).

One year later, on July 12, 2011, the CHOICES Delaware organization attempted to create a listening and spoken Llanguage program in the Delaware School for the Deaf and Statewide Programs for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. However, their attempt was unsuccessful, as stated in the CHOICES Delaware Position Paper. Ursula Schultz, a former deaf employee at the Delaware School for the Deaf, reported that the CHOICES Delaware organization was pushing for the implementation of listening and spoken language educational practices based on AGBell's principles for LSL in their early childhood classes. They believed all children with hearing aids or cochlear implants only need LSL. The group has been actively lobbying state officials to make these changes happen (Ursula Schultz, personal communication, February 12, 2012).

Like the South Dakota School for the Deaf, in 2011, Delaware and Indiana also worked to make Listening & Spoken language (LSL) a legal option for Deaf children in their state schools for the deaf. Indiana succeeded in their mission. Superintendent Noyce enthusiastically shared at the Utah State Office of Education's Deaf National Agenda Committee meeting that Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels sought his advice on implementing the two-track program and outreach services provided by the Utah School for the Deaf during the Indiana Deaf community's protest. Superintendent Noyce further stated that the Illinois School for the Deaf and the New Jersey School for the Deaf will follow in the footsteps of the Indiana School for the Deaf by adopting the Utah School for the Deaf's delivery services model (Steven W. Noyce, personal communication, March 12, 2010). On top of that, the Delaware School for the Deaf, which provides bilingual education in American Sign Language and English, was pressured to offer the LSL option by the LSL-promoting CHOICES Delaware organization, created in 2009. Fortunately, on September 10, 2010, Delaware Governor Jack Markell signed House Bill 283, the Delaware Hard of Hearing Children's Bill of Rights, into law to safeguard ASL/English bilingual education. Texas, Colorado, and California have also implemented similar legislation (www.christina.k12.de.us/DSPDHH/DHHBillofRights.htm).

One year later, on July 12, 2011, the CHOICES Delaware organization attempted to create a listening and spoken Llanguage program in the Delaware School for the Deaf and Statewide Programs for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. However, their attempt was unsuccessful, as stated in the CHOICES Delaware Position Paper. Ursula Schultz, a former deaf employee at the Delaware School for the Deaf, reported that the CHOICES Delaware organization was pushing for the implementation of listening and spoken language educational practices based on AGBell's principles for LSL in their early childhood classes. They believed all children with hearing aids or cochlear implants only need LSL. The group has been actively lobbying state officials to make these changes happen (Ursula Schultz, personal communication, February 12, 2012).

The CHOICES Delaware organization advocated for speech and auditory therapy services for Deaf and hard of hearing students, particularly those with hearing parents. They argued that such therapy was essential for the student's overall development. While they recognized the value of ASL/English bilingual educational programs for Deaf and hard of hearing children of Deaf parents, they believed that not all hearing families received speech and auditory services, making it essential to advocate for such services. The administration of Delaware School for the Deaf supported the ASL/English bilingual program, which did not sit well with the CHOICES Delaware organization (Ursula Schultz, personal communication, February 12, 2012). The organization looked for support beyond Delaware to push for change. They learned about Utah and the changes made by then-USDB Superintendent Noyce in expanding the LSL Program at the Utah School for the Deaf, which they found to be an excellent educational model. To promote the two-track program and its outreach services model, the CHOICES Delaware organization invited Superintendent Noyce to the Delaware Conference on Deaf Education on June 11, 2011, as a keynote speaker (Jacob Dietz, personal communication, April 21, 2011).

Over more than ten years, the CHOICES Delaware organization worked to bring the LSL option to the Delaware School for the Deaf. Their efforts did not yield results, which led the American Civil Liberties Union of Delaware (ACLU-DE), a local affiliate of the nationwide ACLU organization, to file a complaint. The complaint asked the US Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights to investigate the Delaware Department of Education for lack of access to LSL therapy and over-referrals to the Delaware School for the Deaf. When the ACLU of Delaware received a response from the Deaf community expressing their concerns and perspectives, they published a position statement on December 27, 2023, stating that they were reviewing it (Deaf and Hard of Hearing Education, ACLU-Delaware, December 27, 2023). Sara Nović, a Deaf professor and novelist, launched a Change.org petition calling for a complete withdrawal of the ACLU-DE's case. The petition garnered more than 30,000 signatures. Sara argued that it is false and dangerous to force a choice between English and ASL, as this can lead to language deprivation syndrome. The ACLU-Delaware case, which advocated for LSL, puts Deaf children at risk of having limited access to language during their childhood years. When ACLU-Delaware joined forces with the CHOICES Delaware organization, they faced pushback from the Deaf community and Deaf education professionals. Later, ACLU-Delaware removed the post from their website (Abenchuchan, The Daily Moth: Deaf News, January 10, 2024).

Over more than ten years, the CHOICES Delaware organization worked to bring the LSL option to the Delaware School for the Deaf. Their efforts did not yield results, which led the American Civil Liberties Union of Delaware (ACLU-DE), a local affiliate of the nationwide ACLU organization, to file a complaint. The complaint asked the US Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights to investigate the Delaware Department of Education for lack of access to LSL therapy and over-referrals to the Delaware School for the Deaf. When the ACLU of Delaware received a response from the Deaf community expressing their concerns and perspectives, they published a position statement on December 27, 2023, stating that they were reviewing it (Deaf and Hard of Hearing Education, ACLU-Delaware, December 27, 2023). Sara Nović, a Deaf professor and novelist, launched a Change.org petition calling for a complete withdrawal of the ACLU-DE's case. The petition garnered more than 30,000 signatures. Sara argued that it is false and dangerous to force a choice between English and ASL, as this can lead to language deprivation syndrome. The ACLU-Delaware case, which advocated for LSL, puts Deaf children at risk of having limited access to language during their childhood years. When ACLU-Delaware joined forces with the CHOICES Delaware organization, they faced pushback from the Deaf community and Deaf education professionals. Later, ACLU-Delaware removed the post from their website (Abenchuchan, The Daily Moth: Deaf News, January 10, 2024).

On May 17, 2011, just three days after the CHOICES Delaware conference, Governor Mitch Daniels of Indiana appointed two new members to the board that governs the Indiana School for the Deaf. This school is renowned as a national leader in bilingual education for Deaf and hard of hearing students. However, there was a concern that the two newly appointed members were not affiliated with bilingual education. What made the matter worse was that these two new members were parents of Deaf children who did not attend ISD, the school they were chosen to oversee. Out of the six members on the board, only one was Deaf while the other five were hearing. Upon hearing the news, many parents were outraged by the new appointments, believing that it was a tactic to eliminate American Sign Language (ASL) at the school and return it to oralism. They were also baffled and concerned about anticipated changes in school academic instruction (6News, May 19, 2011).

Marvin T. Miller, who is the president of the Indiana Association of the Deaf and a Deaf parent to four children, requested that the ISD School Board provide equal representation for the Deaf community. However, Governor Daniels declined to reverse the selections. In response, the parents and the Indiana Deaf community collaborated with the Indiana Association of the Deaf and the Parent Teacher Counselor Organization, organizing a rally on June 7, 2011 (Marvin Miller, personal communication, July 15, 2011).

Marvin T. Miller, who is the president of the Indiana Association of the Deaf and a Deaf parent to four children, requested that the ISD School Board provide equal representation for the Deaf community. However, Governor Daniels declined to reverse the selections. In response, the parents and the Indiana Deaf community collaborated with the Indiana Association of the Deaf and the Parent Teacher Counselor Organization, organizing a rally on June 7, 2011 (Marvin Miller, personal communication, July 15, 2011).

During a rally in 2011, Howard Rosenblum, Chief Executive Officer of the National Association of the Deaf, expressed his concerns about the new board members of Indiana School for the Deaf. Howard questioned the board members' commitment to preserving the school's goals, as they had sent their own children to other schools. The school board was in a long-standing dispute over assimilating Deaf individuals into hearing society. Some believed that Deaf children should use sign language and go to state schools for the deaf, while others argued that mainstreaming Deaf students with hearing children in regular classrooms would improve their benefits, particularly with the availability of cochlear implants (6News, June 7, 2011). The Utah Deaf Education Core Group suspected that the two Indiana LSL board members would wish to replicate the Utah Schools for the Deaf's two-track model, as the governor refused to compromise even after the rally.

According to Jacob Dietz, Steven Noyce has transformed the Utah School for the Deaf into one of the nation's best state-run oral programs since assuming the superintendent of USDB in 2009 (Jacob Dietz, personal communication, April 21, 2011). In addition, Dr. White advocated for the passage of HB 1367 before the Indiana Legislature despite protests from the Indiana Deaf community. This move had significant impacts on deaf education. When the Utah Deaf community learned of the 1962 inception of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf and Superintendent Noyce's actions, they fought back with unwavering determination. Their movement, which spanned over 50 years from 1962 to 2011, was a testament to their resilience. However, the community staunchly resisted Superintendent Noyce's gradual funding reduction for the ASL/English bilingual Program as the LSL program expanded.

Superintendent Noyce's changes had a significant emotional impact on both the Utah Deaf community and parents of Deaf children. His revamp of the Parent Infant Program, which allegedly pressured parents to choose the LSL option, was similar to the ineffective "Y" system of the 1960s. From 2009 to 2011, his limitations on educational services led to parental manipulation, causing significant emotional distress. The Parent Infant Program offered services to parents of Deaf or hard of hearing children aged 0 to 3. Previously, parents waited until their child started preschool before focusing on either the signing or speaking routes. However, during Superintendent Noyce's PIP years, he encouraged parents to choose either ASL/English or LSL as early as possible because those early years were critical for language development (Winters, The Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 2011). As of February 2011, 74% of parents enrolled in the Parent Infant Program had chosen LSL, 15% chose ASL, and the rest remained undecided. The Utah School for the Deaf enrolled 170 infants and toddlers, with more LSL specialists than ASL specialists receiving training. Parents' demand for speech and auditory services prompted this change (Winters, The Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 2011).

Advocates for bilingual education expressed valid concerns about Superintendent Noyce's favoritism towards oral programs over traditional deaf education in American Sign Language (Winters, The Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 2011). They argued that ASL was crucial in uniting the Deaf community and fostering a Deaf identity, as it was more easily accessible to visual learners. Although Superintendent Noyce claimed to support family choice, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group observed that he had effectively limited their options, leading to a requirement to pick one ASL or LSL. For example, when PIP parents chose ASL, speech services were removed, while signing services were removed when they chose LSL. Many parents wanted both options, but it was an "either/or" situation.

Superintendent Noyce's changes had a significant emotional impact on both the Utah Deaf community and parents of Deaf children. His revamp of the Parent Infant Program, which allegedly pressured parents to choose the LSL option, was similar to the ineffective "Y" system of the 1960s. From 2009 to 2011, his limitations on educational services led to parental manipulation, causing significant emotional distress. The Parent Infant Program offered services to parents of Deaf or hard of hearing children aged 0 to 3. Previously, parents waited until their child started preschool before focusing on either the signing or speaking routes. However, during Superintendent Noyce's PIP years, he encouraged parents to choose either ASL/English or LSL as early as possible because those early years were critical for language development (Winters, The Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 2011). As of February 2011, 74% of parents enrolled in the Parent Infant Program had chosen LSL, 15% chose ASL, and the rest remained undecided. The Utah School for the Deaf enrolled 170 infants and toddlers, with more LSL specialists than ASL specialists receiving training. Parents' demand for speech and auditory services prompted this change (Winters, The Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 2011).

Advocates for bilingual education expressed valid concerns about Superintendent Noyce's favoritism towards oral programs over traditional deaf education in American Sign Language (Winters, The Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 2011). They argued that ASL was crucial in uniting the Deaf community and fostering a Deaf identity, as it was more easily accessible to visual learners. Although Superintendent Noyce claimed to support family choice, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group observed that he had effectively limited their options, leading to a requirement to pick one ASL or LSL. For example, when PIP parents chose ASL, speech services were removed, while signing services were removed when they chose LSL. Many parents wanted both options, but it was an "either/or" situation.

Deaf student Toni Ekenstam gets auditory training from Steven Noyce, a teacher of the deaf. Toni is taught to lip read and communicate with her own voice, one of several methods used to teach deaf children at the Utah School for the Deaf @ Deseret News, March 8, 1973. Deseret News Photo by Chief Photographer Don Groyston

Although the Utah School for the Deaf offered both listening and spoken language and ASL/English bilingual programs in 2011, they encountered issues comparable to those of the 1960s and 1970s. Parents had to choose between teaching Deaf children to speak and educating them in sign language. Superintendent Noyce took pride in the fact that the Utah School for the Deaf was the only state school that offered purely oral or bilingual education. Nonetheless, most other state schools used research to shape their current programs. The Utah Deaf Education Core Group additionally disapproved the Utah School of the Deaf's dual-track program. This was the same controversy that arose in 1962 when the Utah State Board of Education approved a dual-track educational system for the deaf (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). Additional information on the school's program is available below.

Private deaf schools all over the country have adopted the oral curriculum. There was a debate about whether the Utah School for the Deaf, a state-funded school, should offer both programs, as neighborhood schools could cater to Deaf and hard of hearing students who preferred speech services. However, the Utah School for the Deaf should have given equal importance to both available options. The publication of "The National Agenda: Moving Forward on Achieving Educational Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students" in April 2005 outlined standards to overcome biases in philosophy, placement, communication, and service delivery. At that time, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group felt that Superintendent Noyce, a graduate of Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Teacher Training Program, prioritized an oral approach at the University of Utah, which was a hindrance to expanding the bilingual program at the Utah School for the Deaf due to LSL bias. They wanted to ensure that his successor didn't take any steps backward with the Utah School for the Deaf, as Superintendent Noyce did. You can find further information about the Utah Deaf Education Core Group's disagreement with Superintendent Noyce on the "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream" webpage.

The Utah School for the Deaf is regards as a "beacon" by the LSL community. Unlike other state schools for the Deaf, which only offered a single teaching philosophy curriculum in ASL, the Utah School for the Deaf took pride in its unique approach of offering both Listening & Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual options. Dr. Karl White and Superintendent Noyce played an instrumental role in promoting LSL services through state legislation, advocating for the two-track program and outreach services strategy. However, their involvement also caused some tension as the LSL community sought to model their operations after the USD's successful program, which interfered with other state schools for the deaf. The Deaf community in their respective states was fighting hard to protect their ASL/English bilingual curriculum, and Noyce and White's involvement had an impact on their efforts. To preserve and protect state schools for the deaf, the Deaf community needs to remain vigilant.

Private deaf schools all over the country have adopted the oral curriculum. There was a debate about whether the Utah School for the Deaf, a state-funded school, should offer both programs, as neighborhood schools could cater to Deaf and hard of hearing students who preferred speech services. However, the Utah School for the Deaf should have given equal importance to both available options. The publication of "The National Agenda: Moving Forward on Achieving Educational Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students" in April 2005 outlined standards to overcome biases in philosophy, placement, communication, and service delivery. At that time, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group felt that Superintendent Noyce, a graduate of Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Teacher Training Program, prioritized an oral approach at the University of Utah, which was a hindrance to expanding the bilingual program at the Utah School for the Deaf due to LSL bias. They wanted to ensure that his successor didn't take any steps backward with the Utah School for the Deaf, as Superintendent Noyce did. You can find further information about the Utah Deaf Education Core Group's disagreement with Superintendent Noyce on the "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream" webpage.

The Utah School for the Deaf is regards as a "beacon" by the LSL community. Unlike other state schools for the Deaf, which only offered a single teaching philosophy curriculum in ASL, the Utah School for the Deaf took pride in its unique approach of offering both Listening & Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual options. Dr. Karl White and Superintendent Noyce played an instrumental role in promoting LSL services through state legislation, advocating for the two-track program and outreach services strategy. However, their involvement also caused some tension as the LSL community sought to model their operations after the USD's successful program, which interfered with other state schools for the deaf. The Deaf community in their respective states was fighting hard to protect their ASL/English bilingual curriculum, and Noyce and White's involvement had an impact on their efforts. To preserve and protect state schools for the deaf, the Deaf community needs to remain vigilant.

The Oral and Mainstream Education

Movements in Utah

Movements in Utah

Since 1962, the oral and mainstream education movements have significantly shaped deaf education in Utah, with Dr. Grant B. Bitter at the forefront. His 25-year tenure, from 1962 to 1987, was instrumental in driving this movement forward. In 1962, the Utah School for the Deaf implemented the dual-track program, also known as the "Y" system, as a result of the Utah Council for the Deaf, a group of parents' efforts in oral advocacy (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962). This policy required all Deaf students to start the oral program during elementary school. It only allowed them to transfer to the simultaneous communication department if they had not succeeded in the oral program by the end of the sixth year of schooling or the age of 12 (The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

The Ogden's residential school also separated its oral and simultaneous communication programs, each with its own classrooms, dormitory facilities, dining halls, recess periods, and extracurricular activities, except the athlete programs, which were open to all students due to a player shortage (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). The most significant events were the student strikes in 1962 and 1969, which directly resulted from dissatisfaction with the dual-track program segregation system. Unfortunately, these strikes went unheard.

Following the 1962 protest against social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a steadfast advocate for oral and mainstream education, and his oral supporters suspected that the Utah Association of the Deaf had organized the student strike. The Utah State Board of Education conducted an investigation but found no evidence of any connection between the students and the Utah Association for the Deaf (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). In the face of societal segregation, the simultaneous communication students demonstrated their unwavering determination and courage by staging their own protests.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

Following the 1962 protest against social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a steadfast advocate for oral and mainstream education, and his oral supporters suspected that the Utah Association of the Deaf had organized the student strike. The Utah State Board of Education conducted an investigation but found no evidence of any connection between the students and the Utah Association for the Deaf (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). In the face of societal segregation, the simultaneous communication students demonstrated their unwavering determination and courage by staging their own protests.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

The Implementation

of the The Two-Track Program

at the Utah School for the Deaf

of the The Two-Track Program

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Another round of students' acts of resistance during the 1969 walkout protest against the continued enforcement of "Y" social segregation in the dual-track program was a defining moment in history, echoing the 1962 student protest at the Utah School for the Deaf. Despite not achieving the desired results, they found new ways to voice their discontent. Some sign language students boldly crossed the oral department hallway, while others took the simultaneous communication department route. This act of defiance broke the "Y" system rule, which had designated these spaces as 'off-limits' in order to maintain a 'clean' communication environment. Students even confronted their oral teachers, accusing them of oppression and dominance (Raymond Monson, personal communication, November 9, 2010). For nearly a decade, the Utah Association for the Deaf, in collaboration with the Parent-Teacher-Student Association, comprised supportive parents who advocated for sign language and fought against the "Y" system. Despite years of dismissal and opposition, their unwavering determination and resilience in the face of social segregation are truly admirable.

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, when faced with a challenging situation, sought assistance from his boss, Dr. Jay J. Campbell. Dr. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Campbell, a sign language interpreter and the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, had been a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community. Motivated by his concern for the welfare of Deaf children, he took the initiative to create the two-track program, a new instrument system that replaced the "Y" system (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Campbell, 1977; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). His dedication and commitment to the cause are genuinely inspiring.

Ned C. Wheeler, who became deaf at the age of 13 and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1933, was the chair of the USDB Governor's Advisory Council. He proposed the "two-track program" in response to various events, including Dr. Campbell's proposal, student strikes in 1962 and 1969, and opposition from the Parent Teacher Student Association to the "Y" system policy. On December 28, 1970, the Utah State Board of Education authorized a new policy, paving the way for the Utah School for the Deaf to operate a two-track program with choices, eliminating the "Y" system. This new program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011, Recommendations on Policy for the Utah School for the Deaf, 1970; Deseret News, December 29, 1970).

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, when faced with a challenging situation, sought assistance from his boss, Dr. Jay J. Campbell. Dr. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Campbell, a sign language interpreter and the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, had been a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community. Motivated by his concern for the welfare of Deaf children, he took the initiative to create the two-track program, a new instrument system that replaced the "Y" system (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Campbell, 1977; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). His dedication and commitment to the cause are genuinely inspiring.

Ned C. Wheeler, who became deaf at the age of 13 and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1933, was the chair of the USDB Governor's Advisory Council. He proposed the "two-track program" in response to various events, including Dr. Campbell's proposal, student strikes in 1962 and 1969, and opposition from the Parent Teacher Student Association to the "Y" system policy. On December 28, 1970, the Utah State Board of Education authorized a new policy, paving the way for the Utah School for the Deaf to operate a two-track program with choices, eliminating the "Y" system. This new program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011, Recommendations on Policy for the Utah School for the Deaf, 1970; Deseret News, December 29, 1970).

However, while supervising the Utah School for the Deaf, Dr. Campbell noticed that parents were often unaware of their children's educational and communication options (Campbell, 1977). Despite the Utah State Board of Education releasing policies in 1970, 1977, and 1998, the Utah School for the Deaf's Communication Guidelines did not provide parents with a wide range of choices. This lack of clarity resulted in ineffective placement tactics due to the prevalent oral bias. On April 14, 1977, Dr. Campbell presented his 200-page study report concerning the Utah School for the Deaf at the Utah State Board of Education. He also sought to improve the school's education system through more equitable evaluation and placement methods. However, Dr. Bitter, a professor at the University of Utah at the time, vehemently opposed Dr. Campbell's research, accusing it of containing falsehoods and drawing unfounded conclusions about the University of Utah's Teacher Oral Training Program and educational programs across the state (G.B. Bitter, personal communication, March 6, 1978). The presentation was heated, with over 300 parents supporting the oral method and applauding Dr. Bitter and Peter Viahos, an Ogden attorney and father of a Deaf daughter, as they presented their arguments (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977).

A group of parents, under the influence of Dr. Bitter, petitioned the Utah State Board of Education. They sought to suspend Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study, citing its inconclusive nature. Also, dissatisfied with his research findings, they demanded his termination (Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). Approximately 50 to 60 Deaf individuals attended the meeting (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Those attendees were Ned C. Wheeler, W. David Mortensen, Lloyd Perkins, Dennis Platt, Kenneth L. Kinner, and others.

Dr. Bitter, a spokesperson for the oral advocates, presented Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, with three options:

Dr. Talbot's response to Dr. Bitter's appeal sparked a firestorm of tension. The Deaf group fiercely opposed the State Board's decision to reassign Dr. Campbell within the Utah State Office of Education. Their dissatisfaction was intense, leading them to express their protest by stomping their feet on the floor. In his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter described the scene as highly emotional and chaotic, prompting him to consider leaving the room. Concerned about the escalating situation, Dr. Talbot asked the Deaf community members to leave the room (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Disagreements still exist about what the Deaf people did during the meeting, as different versions of what happened differ.

The Utah State Board of Education accepted Dr. Campbell's report and supporting documentation. However, despite the controversy surrounding his analysis, which included data from independent researchers, they disregarded all of his recommendations (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977). This decision had consequences, as Dr. Campbell's plan crumbled down, including a two-year study to improve education through fair assessment and placement procedures. His plan was buried and forgotten (Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

The mental trend of the "Y" system in the two-track program, with prevalent oral bias, persisted. This biased information had a profound impact, limiting the choices parents could make for their Deaf children's education and communication. Although Dr. J. Jay Campbell tried to provide fair information in the 1970s, Dr. Bitter opposed his efforts because he believed that total communication was a concept, not a word, and also a philosophy, not a method (Campbell, 1977; Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, August 20, 1977, p. 25; Bitter, Concern with Deaf Center Paper, 1985). In 2010, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group challenged this biased approach and advocated for unbiased and equal information. Superintendent Steven W. Noyce of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, an oral advocate and former university student of Dr. Bitter, as well as a long-time teacher and school director, created the Parent Infant Program Orientation to provide parents with fair and balanced information. However, parents still had to choose an "either/or" selection between ASL/English bilingual (replaced total communication) or listening and spoken language (replace oral) options for their children's education and communication, which resulted in the expansion of the listening and spoken program because the majority of Deaf children are born to hearing parents.

Dr. Bitter, a spokesperson for the oral advocates, presented Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, with three options:

- Removing Dr. Campbell from his position;

- Assigning him to another position; or

- Requesting a grand jury investigation into the evidence demonstrating how oral Deaf individuals were intimidated by some of the state's programs (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

Dr. Talbot's response to Dr. Bitter's appeal sparked a firestorm of tension. The Deaf group fiercely opposed the State Board's decision to reassign Dr. Campbell within the Utah State Office of Education. Their dissatisfaction was intense, leading them to express their protest by stomping their feet on the floor. In his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter described the scene as highly emotional and chaotic, prompting him to consider leaving the room. Concerned about the escalating situation, Dr. Talbot asked the Deaf community members to leave the room (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Disagreements still exist about what the Deaf people did during the meeting, as different versions of what happened differ.

The Utah State Board of Education accepted Dr. Campbell's report and supporting documentation. However, despite the controversy surrounding his analysis, which included data from independent researchers, they disregarded all of his recommendations (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977). This decision had consequences, as Dr. Campbell's plan crumbled down, including a two-year study to improve education through fair assessment and placement procedures. His plan was buried and forgotten (Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

The mental trend of the "Y" system in the two-track program, with prevalent oral bias, persisted. This biased information had a profound impact, limiting the choices parents could make for their Deaf children's education and communication. Although Dr. J. Jay Campbell tried to provide fair information in the 1970s, Dr. Bitter opposed his efforts because he believed that total communication was a concept, not a word, and also a philosophy, not a method (Campbell, 1977; Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, August 20, 1977, p. 25; Bitter, Concern with Deaf Center Paper, 1985). In 2010, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group challenged this biased approach and advocated for unbiased and equal information. Superintendent Steven W. Noyce of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, an oral advocate and former university student of Dr. Bitter, as well as a long-time teacher and school director, created the Parent Infant Program Orientation to provide parents with fair and balanced information. However, parents still had to choose an "either/or" selection between ASL/English bilingual (replaced total communication) or listening and spoken language (replace oral) options for their children's education and communication, which resulted in the expansion of the listening and spoken program because the majority of Deaf children are born to hearing parents.

Jeff W. Pollock, a member of the USDB Advisory Council representing the Utah Deaf community, requested on February 10, 2011, that the Utah School for the Deaf implement the guidelines titled "The National Agenda: Moving Forward on Achieving Educational Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students" to address philosophical, placement, communication, and service delivery biases. One of the members of the Advisory Council wondered if the Deaf National Agenda was solely based on ASL. He clarified that the Deaf National Agenda does not exclusively rely on ASL but instead emphasizes the holistic development of each child, supporting both ASL and spoken language, unlike the current system's "either/or" approach. Jeff then addressed Superintendent Noyce in the eyes and stated that the USD has reverted to the inefficient "Y" system of the last 30–40 years, with an oral OR sign, and is not providing both ASL and LSL to parents who want both options. Superintendent Noyce remained silent about the subject. The "Y" system mental trend in the two-track program with prevalent oral bias persisted until Joel Coleman, superintendent of Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind, and Michelle Tanner, associate superintendent of Utah Schools for the Deaf, took action. Creating the Hybrid Program in 2016 was a significant step towards removing the requirement for parents to choose between the two programs "either/or." Their innovative approach is crucial and brings hope for unbiased and equal information. More information about the hybrid program can be found at the end of this webpage.

Suffice it to say, Dr. Grant B. Bitter was a prominent figure in Utah's oralism and mainstreaming movement, which had a significant impact on deaf education in Utah since 1962, despite the new two-track program and the school's option guidelines. As a result of his efforts, the number of students attending Ogden's residential school for Deaf students decreased, and the quality of education also declined. The mainstreaming approach gained popularity but left many alums heartbroken.

Controversy with Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

the Father of Mainstreaming

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter, who opposed anyone who stood in the way of his goals of promoting oral and mainstream education, has formally requested the job removal of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, both respected advocates for sign language. He believed they were interfering with his mission. Additionally, he expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, feeling it did not align with his educational goals. He also asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected committee chairperson, to resign because she invited representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he saw as a shift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf, in the face of Dr. Bitter's opposition, demonstrated remarkable resilience, marking a significant turning point in their history and inspiring others with their strength and determination.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. His journey began at the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked as a teacher and curriculum coordinator. His passion for education led him to become a director and professor in the Teacher Training Program, where he focused primarily on oral education under the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. Dr. Bitter also served as the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

The Implementation of the Dual-Track Program,

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

In the fall of 1962, the Utah Deaf community was surprised by the revolutionary changes at the Utah School for the Deaf, which introduced the dual-track program, also commonly known as the "Y" system. The unexpected change had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children, evoking a sense of empathy within the community. The Utah Association of the Deaf, which advocated for sign language, was unaware that the Utah Council for the Deaf had spearheaded the change, advocating for speech-based instruction and successfully pushing for its implementation at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962). It is believed that Dr. Bitter was a member of this council. The dual-track program provided an oral program in one department and a simultaneous communication program in another department, which was later replaced by a combined system. However, the dual-track policy mandated that all Deaf children begin with the oral program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Gannon, 1981). The Utah State Board of Education, a key player in educational policy, approved this policy reform on June 14, 1962, with endorsement from the Special Study Committee on Deaf Education (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). The newly hired superintendent, Robert W. Tegeder, accepted the parents' proposals and initiated changes to the school system (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter, 1962; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). This new program not only affected the lives of Deaf children but also their families.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

As a result of the "Y" system's implementation, the Utah School for the Deaf had to undergo significant changes. The school had to hire more oral teachers and establish speech as the primary mode of communication, shifting the focus of the learning environment. The dual-track program initially placed all elementary school students in the oral department, transferring them to the simultaneous communication department only if they failed in the oral program. This approach was based on the belief that early development of oral skills was crucial for Deaf students, with sign language learning considered a secondary focus. The change in focus and the increased hiring of oral teachers had a significant impact on the school's learning environment, altering its dynamics and atmosphere (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, some changes were made at the Utah School for the Deaf without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were surprised to find out about the changes. These changes caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy.

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, some changes were made at the Utah School for the Deaf without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were surprised to find out about the changes. These changes caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy.

Dr. Bitter also had significant power as a parental figure and used it to push for oralism, making it difficult for the Utah Association for the Deaf to challenge him. When the Teacher Training Program in the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah closed in 1986, he retired in 1987 (Bitter, A Summary Report for Tenure, March 15, 1985). Today, the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah offers a Specialization in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program. While the curriculum does include American Sign Language classes, it still places a greater emphasis on Listening and Spoken Language. This reflects the impact that Dr. Bitter, who passed away in 2000, continues to have on deaf education in Utah. To learn more about the evolving mainstreaming movement, visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective' webpage.

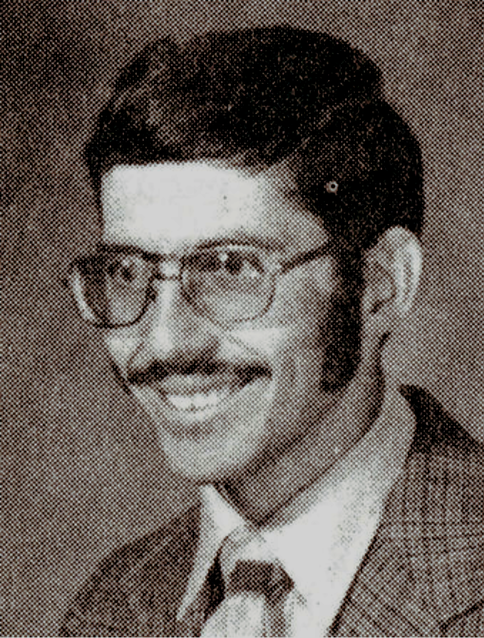

Battling with Steven W. Noyce,

an Oral Promoter

an Oral Promoter

The Utah Deaf community was concerned that Steven W. Noyce, a long-time teacher and director of the Utah School for the Deaf, would seek to carry on Dr. Bitter's legacy, jeopardizing the ASL/English bilingual program they had worked so hard to establish when the Utah State Board of Education elected him superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind in August 2009. The state board disregarded the Utah Deaf community's outcry.

Steven Noyce was no stranger to the Utah Deaf community, having graduated from the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah between 1965 and 1972 (LinkedIn: Steven Noyce). We were concerned about his advocacy for oral education. In response, Ella Mae Lentz, a co-founder of the Deafhood Foundation and a vocal champion for deaf education, proposed founding the Deaf Education Core Group in April 2010. The group aimed to protect ASL/English bilingual education and fight inequality in the deaf education system.

The Utah Deaf Education Core Group spent a year trying to persuade the Utah State Board of Education to terminate Steven Noyce's two-year contract from 2010 to 2011. However, the board rejected their efforts and extended his contract for another two years, from 2011 to 2013. His contract was eventually terminated by the Utah State Board of Education in 2013, but the reason for the termination remains unknown.

Battling with Dr. Karl R. White,

a Global Oral Leader

a Global Oral Leader