Construction-In-Progress

Biographies of Prominent

Utah Deaf Women

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

Women's Studies is a fascinating field, particularly when it comes to understanding the influence of Deaf women on their communities. In this context, it's crucial to recognize and celebrate the achievements of Utah Deaf Women's History. By acknowledging the heroes within the Utah Deaf community, we can draw inspiration from their contributions, which have significantly impacted the community and raised state recognition outside of Utah.

The lives of Deaf women have seen progress, including gaining the right to vote, access to education, employment opportunities, and involvement in advocacy organizations. Women continue to face marginalization and underrepresentation in politics, education, social and economic status, and professional standing despite outnumbering men in education and the workforce. Utah ranks last in the nation for women's equality and representation in leadership, legal protections, rights, advanced degree attainment, workplace environments, and sexist attitudes. In Utah, women graduate from college at a lower rate than men, and there is a wage disparity between the genders.

Women across the country are actively promoting, educating, and implementing programs to achieve gender equality. However, Deaf women have been marginalized in various aspects, such as education, socialization, economics, professionalism, and politics. This has led to potential double discrimination, as highlighted in The Deaf American on February 6, 1980. It's important to acknowledge the challenges that Deaf women continue to face, challenges that often go unnoticed. These challenges hinder their ability to lead fulfilling lives comparable to those of their hearing counterparts. Those who have surmounted these obstacles and excelled in their lives, education, and careers deserve recognition and reward.

This webpage is a platform designed to inspire and empower Deaf women in Utah. It encourages them to serve the Deaf community and improve its quality of life. The webpages 'Outstanding Resilience Contributed to the Success of Utah's Deaf Women's History' and 'Outstanding Contributions in the Early History of Utah's Deaf and Non-Deaf Women' are not only invaluable resources, but also a testament to the strength and resilience of women throughout history. They provide a thorough understanding of the challenges and oppressions women have faced, which are directly relevant to our cause.

Inspired by the iconic poster of Rosie the Riveter during World War II, which symbolizes female empowerment, as a Deaf feminist, I am confident that the featured role models on this webpage will not only inspire but also empower Deaf women to assume leadership roles in the future, both locally and nationally. For a more detailed look into Deaf women's history, I recommend visiting the website 'Deaf Women in History' created by Dr. Karen Christie. Dr. Christie, a retired professor emeritus at NTID/RIT, has taught English, Deaf Women's Studies, ASL, and Deaf Literature. Her website is a valuable source of information about the history of Deaf women. I want to acknowledge and commend Utah Deaf women for their dedication and perseverance in striving for a respectable life and supporting others.

Religion, particularly The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has been a significant and enduring influence on Utah's history. This influence extends to the Utah Deaf community, making it an integral part of our collective heritage. The biographies of these interpreters, which often include their religious affiliations, provide a unique perspective on their lives and contributions. These biographies not only serve as a valuable resource for the interpreters' families, aiding in preserving history and exploring their lineage, but also contribute to the broader narrative of Utah's cultural and religious diversity. Furthermore, these biographies preserve the life stories of these individuals for future generations to appreciate and remember.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading the 'Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Women' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The lives of Deaf women have seen progress, including gaining the right to vote, access to education, employment opportunities, and involvement in advocacy organizations. Women continue to face marginalization and underrepresentation in politics, education, social and economic status, and professional standing despite outnumbering men in education and the workforce. Utah ranks last in the nation for women's equality and representation in leadership, legal protections, rights, advanced degree attainment, workplace environments, and sexist attitudes. In Utah, women graduate from college at a lower rate than men, and there is a wage disparity between the genders.

Women across the country are actively promoting, educating, and implementing programs to achieve gender equality. However, Deaf women have been marginalized in various aspects, such as education, socialization, economics, professionalism, and politics. This has led to potential double discrimination, as highlighted in The Deaf American on February 6, 1980. It's important to acknowledge the challenges that Deaf women continue to face, challenges that often go unnoticed. These challenges hinder their ability to lead fulfilling lives comparable to those of their hearing counterparts. Those who have surmounted these obstacles and excelled in their lives, education, and careers deserve recognition and reward.

This webpage is a platform designed to inspire and empower Deaf women in Utah. It encourages them to serve the Deaf community and improve its quality of life. The webpages 'Outstanding Resilience Contributed to the Success of Utah's Deaf Women's History' and 'Outstanding Contributions in the Early History of Utah's Deaf and Non-Deaf Women' are not only invaluable resources, but also a testament to the strength and resilience of women throughout history. They provide a thorough understanding of the challenges and oppressions women have faced, which are directly relevant to our cause.

Inspired by the iconic poster of Rosie the Riveter during World War II, which symbolizes female empowerment, as a Deaf feminist, I am confident that the featured role models on this webpage will not only inspire but also empower Deaf women to assume leadership roles in the future, both locally and nationally. For a more detailed look into Deaf women's history, I recommend visiting the website 'Deaf Women in History' created by Dr. Karen Christie. Dr. Christie, a retired professor emeritus at NTID/RIT, has taught English, Deaf Women's Studies, ASL, and Deaf Literature. Her website is a valuable source of information about the history of Deaf women. I want to acknowledge and commend Utah Deaf women for their dedication and perseverance in striving for a respectable life and supporting others.

Religion, particularly The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has been a significant and enduring influence on Utah's history. This influence extends to the Utah Deaf community, making it an integral part of our collective heritage. The biographies of these interpreters, which often include their religious affiliations, provide a unique perspective on their lives and contributions. These biographies not only serve as a valuable resource for the interpreters' families, aiding in preserving history and exploring their lineage, but also contribute to the broader narrative of Utah's cultural and religious diversity. Furthermore, these biographies preserve the life stories of these individuals for future generations to appreciate and remember.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for taking an interest in reading the 'Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Women' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Acknowledgement

Anne Leahy @ Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, inc.

Anne Leahy @ Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, inc.

I am deeply grateful to Anne Leahy for her generous contributions to the collection of specific individuals, especially a copy of Elizabeth DeLong's biography from The Church History Library of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and for inspiring me to create this "Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Women" webpage.

I would like to thank Doug Stringham for recommending the names of Deaf women for recognition.

I also want to express my gratitude to Valerie G. Kinney for her invaluable support and time spent proofreading this document.

Once again, I'd like to express my appreciation and gratitude to Helen Salas-McCarty for donating her time to proofread and edit the documents.

I want to express my gratitude to Eleanor McCowan for suggesting that I take on the Utah Deaf History project. Without her suggestion, none of this would have been possible.

I also want to thank my colleague, James Fenton, for recommending that I include a summary of each biography.

I am incredibly appreciative of the support and patience of my spouse, Duane Kinner, and my children, Joshua and Danielle, throughout the completion of this project. The "Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Women" webpage would not have been possible without their support. Thank you!

Jodi Becker Kinner

I would like to thank Doug Stringham for recommending the names of Deaf women for recognition.

I also want to express my gratitude to Valerie G. Kinney for her invaluable support and time spent proofreading this document.

Once again, I'd like to express my appreciation and gratitude to Helen Salas-McCarty for donating her time to proofread and edit the documents.

I want to express my gratitude to Eleanor McCowan for suggesting that I take on the Utah Deaf History project. Without her suggestion, none of this would have been possible.

I also want to thank my colleague, James Fenton, for recommending that I include a summary of each biography.

I am incredibly appreciative of the support and patience of my spouse, Duane Kinner, and my children, Joshua and Danielle, throughout the completion of this project. The "Biographies of Prominent Utah Deaf Women" webpage would not have been possible without their support. Thank you!

Jodi Becker Kinner

“When women's true history shall have been written,

her part in the upbuilding of this nation

will astound the world.”

~Abigail Dunaway~

her part in the upbuilding of this nation

will astound the world.”

~Abigail Dunaway~

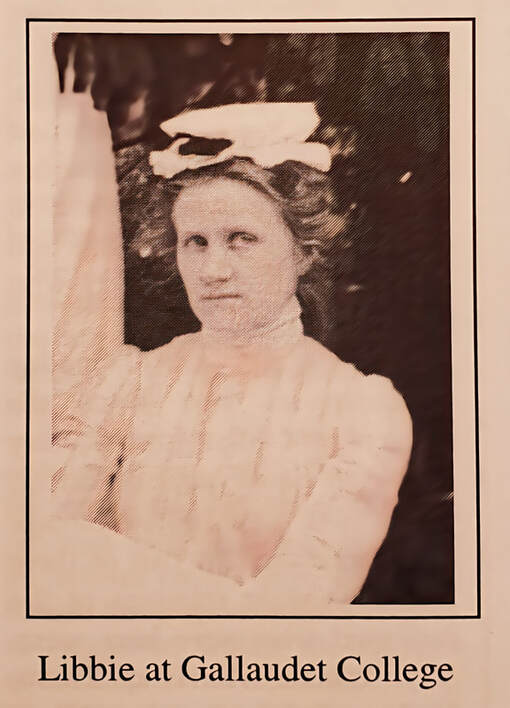

Elizabeth DeLong, Feminist Leader

In 1909, Elizabeth DeLong, also known as Libbie, made history by defeating two male Deaf candidates, becoming the first female Deaf president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, an advocacy organization for accessibility and civil rights of the Utah Deaf community. Additionally, she became the first female Deaf president of a state chapter association of the National Association of the Deaf in the United States. Her victory over two Deaf male candidates in the election, despite the societal barriers, was a significant achievement. Women did not have the right to vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, and the National Association of the Deaf also did not allow Deaf women members to vote in their elections until 1964. Libbie's remarkable accomplishment was a testament to her perseverance, likely inspired by her involvement in Gallaudet's O.W.L.S. presidential election in 1901, a secret society for women now known as Phi Kappa Zeta. Her active participation in Utah's early suffrage movement also fueled her educational, political, and spiritual aspirations. Libbie served as president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1915, delivering a speech advocating for women's suffrage at the end of her second term as president. This speech highlighted her commitment to advocating for women's rights and her role as a trailblazer for Deaf women in leadership positions. Her support for women's suffrage, as well as her significant contributions to the Utah Deaf community and the women's rights movement, continue to serve as inspiration today, underscoring the enduring impact of her work.

The BetterDays2002 website features Libbie's biography, as well as those of other Utah women trailblazers' accomplishments and contributions.

The BetterDays2002 website features Libbie's biography, as well as those of other Utah women trailblazers' accomplishments and contributions.

Please click the links below

to learn more about Elizabeth DeLong

to learn more about Elizabeth DeLong

Libbie was born on April 2, 1877, in Panguitch, Utah, to Albert DeLong and Elizabeth Houston. In 1882, at the age of five, Libbie became deaf due to scarlet fever and smallpox. Her mother, preoccupied with raising her large family, was unable to give Libbie much attention, but Libbie was close to her older sister, Dicey. Dicey taught Libbie how to practice her speech and acted as an "oral" interpreter until 1891, when she went away to attend the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) (Banks & Banks).

When Libbie was 14 years old, her life changed forever after she enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf at the University of Deseret (later renamed the University of Utah) in the fall of 1891 in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her close cousin, John Houston Clark, also known as "John H," who had lost his hearing at the age of 10 from spinal meningitis, also attended the USD at the same time. She started to learn sign language on the school campus and became involved in extracurricular activities. In February 1892, she participated in a demonstration of school activities before the State Legislature. After giving a welcome speech, she also participated in a lip-reading demonstration and narrated a story by someone else. Libbie and her cousin, John H., were also storytellers at the 1893 gathering as members of the Park Literacy Society. During her senior year, she served as an editor for The Eagle, a publication for the Utah School of the Deaf.

When Libbie was 14 years old, her life changed forever after she enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf at the University of Deseret (later renamed the University of Utah) in the fall of 1891 in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her close cousin, John Houston Clark, also known as "John H," who had lost his hearing at the age of 10 from spinal meningitis, also attended the USD at the same time. She started to learn sign language on the school campus and became involved in extracurricular activities. In February 1892, she participated in a demonstration of school activities before the State Legislature. After giving a welcome speech, she also participated in a lip-reading demonstration and narrated a story by someone else. Libbie and her cousin, John H., were also storytellers at the 1893 gathering as members of the Park Literacy Society. During her senior year, she served as an editor for The Eagle, a publication for the Utah School of the Deaf.

Libbie was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She attended the Utah School for the Deaf, which was located at the University of Deseret. She was likely one of the first Deaf-Mute Sunday School students who were also members of the Latter-day Saints (The Daily Enquirer, February 11, 1892).

On June 8, 1897, both Libbie and John H. graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf (The Ogden Standard, May 8, 1897). They were the only two students to graduate from the school in Ogden, Utah, after it relocated to this area in 1896.

On September 15, 1897, the Utah School for the Deaf reached a significant milestone. On this day, Libbie and John H. became the first students from Utah to enroll at Gallaudet College in Washington, DC. This marked a significant turning point in the history of the Utah School for the Deaf. Frank M. Driggs, the superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf and the Blind, played a crucial role in facilitating their journey to Gallaudet College. His dedication and support were vital in helping Libbie and John H. transition to college, where they would embark on a four-year course of study. Frank also enrolled in a one-year teacher training program at Gallaudet College, further aiding their journey (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 15, 1897).

On June 8, 1897, both Libbie and John H. graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf (The Ogden Standard, May 8, 1897). They were the only two students to graduate from the school in Ogden, Utah, after it relocated to this area in 1896.

On September 15, 1897, the Utah School for the Deaf reached a significant milestone. On this day, Libbie and John H. became the first students from Utah to enroll at Gallaudet College in Washington, DC. This marked a significant turning point in the history of the Utah School for the Deaf. Frank M. Driggs, the superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf and the Blind, played a crucial role in facilitating their journey to Gallaudet College. His dedication and support were vital in helping Libbie and John H. transition to college, where they would embark on a four-year course of study. Frank also enrolled in a one-year teacher training program at Gallaudet College, further aiding their journey (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 15, 1897).

The United States government paid for Libbie's Gallaudet education. While at Gallaudet, she was active in acting and writing. During her senior year, Libbie was elected associate editor of the Gallaudet's "The Buff and Blue" publication, where she worked closely with her cousin, John H., also a senior, was appointed editor-in-chief (The Ogden Standard, June 19, 1901; Banks & Banks; Dr. Thomas C. Clark, personal communication, November 13, 2008). According to the Ogden Standard story (1901), "to be elected editor-in-chief of the college paper has always been considered one of the highest honors, and it is of special note that Utah students obtained two of the positions (1.)."

During Libbie's senior year at Gallaudet College, she was elected President of the O.W.L.S., a secret society for women at Gallaudet College, today known as Phi Kappa Zeta, in 1901 (The Buff & Blue, October 1901). The O.W.L.S. was founded by Agatha Tiegal Hanson, an early champion of both deaf and women's rights, in 1892 to address women's barriers in a largely male environment on the Gallaudet campus. When women were first allowed to enroll at Gallaudet College in 1887, they faced gender discrimination. They could only join clubs or organizations if a man invited them. Female students were not allowed to engage in debates with male students at the time. Therefore, the O.W.L.S. club was formed to provide a safe space to debate, study poetry and literature, and form sisterhood bonds (This Week in 19th Amendment History: Agatha Tiegel Hanson, October 17, 1959).

Libbie's graduation from Gallaudet College in 1902 marked a significant milestone in her life. She was the first Utah Deaf female college graduate with a bachelor's degree in domestic arts and domestic science. This achievement was a tremendous inspiration to many. Additionally, she was the first in her family to earn a college education. After returning to Ogden from Washington, DC, on September 3, 1902, she became the first Deaf woman to have a college education, and she began teaching at her alma mater, Utah School for the Deaf, where she taught for fifteen years (Banks & Banks). Her fifteen-year tenure as a school teacher was a testament to her dedication to the Utah Deaf community, a significant achievement in her career.

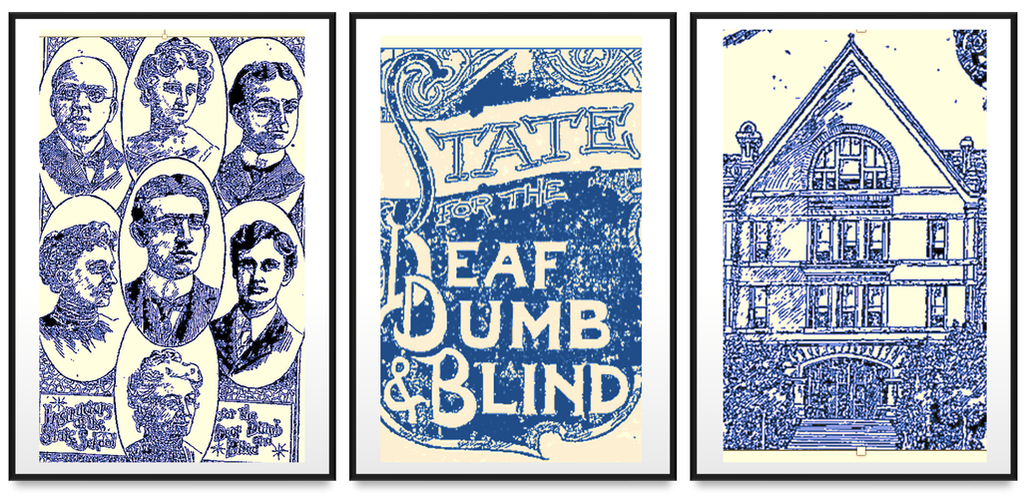

The Utah School for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind, as it was called back then, was featured in the Ogden Daily Standard on December 20, 1902. The staff members were, from top to bottom, L-R: Albert Talage, Catherine King, Elizabeth DeLong, Superintendent Frank M. Driggs (Center), Sarah Whalen, E.S. Henne, and Max W. Woodbury

Since the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) was founded in 1880, affiliated state chapter associations have been established nationwide. In 1909, Libbie proposed the formation of the Utah Association of the Deaf (UAD) to meet social and welfare needs among Utah School for the Deaf alums. Frank M. Driggs, the Superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, approved it (Evans, 1999).

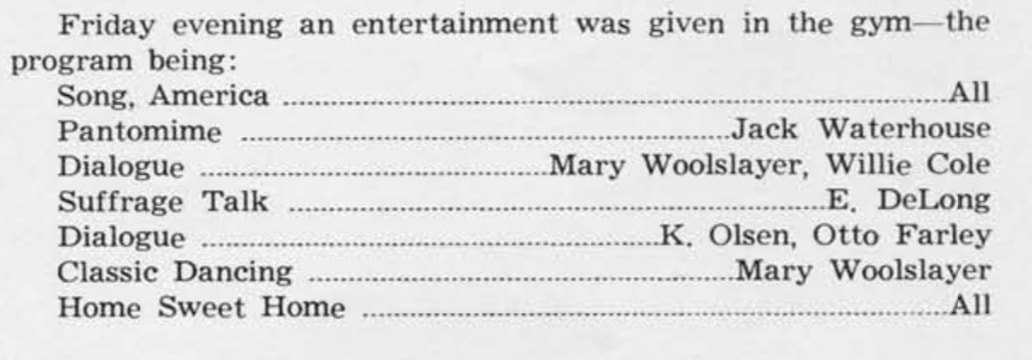

The Utah Association of the Deaf was founded on June 10, 1909, at the Utah School for the Deaf by Superintendent Driggs, and the association grew out of the first-ever alum reunion (Evans, 1999). Libbie won the presidential election by 39 votes the following day, defeating two Deaf male candidates, Paul Mark (2 votes) and Melville J. Matheis (2 votes). As a result, Libbie made history by defeating two male Deaf candidates, becoming the first female Deaf president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, an advocacy organization for accessibility and civil rights of the Utah Deaf community. Additionally, she became the first female Deaf president of a state chapter association of the National Association of the Deaf in the United States. Her victory over two Deaf male candidates in the election, despite the societal barriers, was a significant achievement. Women did not have the right to vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, and the National Association of the Deaf also did not allow Deaf women members to vote in their elections until 1964. Libbie's remarkable accomplishment was a testament to her perseverance, likely inspired by her involvement in Gallaudet's O.W.L.S. presidential election in 1901, a secret society for women now known as Phi Kappa Zeta. Her active participation in Utah's early suffrage movement also fueled her educational, political, and spiritual aspirations. Libbie served as president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1915, delivering a speech advocating for women's suffrage at the end of her second term as president. This speech highlighted her commitment to advocating for women's rights and her role as a trailblazer for Deaf women in leadership positions. Her support for women's suffrage, as well as her significant contributions to the Utah Deaf community and the women's rights movement, continue to serve as inspiration today, underscoring the enduring impact of her work.

The Utah Association of the Deaf was founded on June 10, 1909, at the Utah School for the Deaf by Superintendent Driggs, and the association grew out of the first-ever alum reunion (Evans, 1999). Libbie won the presidential election by 39 votes the following day, defeating two Deaf male candidates, Paul Mark (2 votes) and Melville J. Matheis (2 votes). As a result, Libbie made history by defeating two male Deaf candidates, becoming the first female Deaf president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, an advocacy organization for accessibility and civil rights of the Utah Deaf community. Additionally, she became the first female Deaf president of a state chapter association of the National Association of the Deaf in the United States. Her victory over two Deaf male candidates in the election, despite the societal barriers, was a significant achievement. Women did not have the right to vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, and the National Association of the Deaf also did not allow Deaf women members to vote in their elections until 1964. Libbie's remarkable accomplishment was a testament to her perseverance, likely inspired by her involvement in Gallaudet's O.W.L.S. presidential election in 1901, a secret society for women now known as Phi Kappa Zeta. Her active participation in Utah's early suffrage movement also fueled her educational, political, and spiritual aspirations. Libbie served as president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1915, delivering a speech advocating for women's suffrage at the end of her second term as president. This speech highlighted her commitment to advocating for women's rights and her role as a trailblazer for Deaf women in leadership positions. Her support for women's suffrage, as well as her significant contributions to the Utah Deaf community and the women's rights movement, continue to serve as inspiration today, underscoring the enduring impact of her work.

Shortly after the establishment of the Ogden Branch for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, on February 4, 1917, Libbie served as Superintendent of the Sunday School, working with three Deaf males, Nephi Larsen, 1st Assistant, Grant Morgan, 2nd Assistant, and Loran Savage, Secretary (Historical Record Book 4, 1941–1945; Historical Events & Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf, 1992). Libbie is most likely the first female Deaf superintendent of the Sunday School for the Deaf.

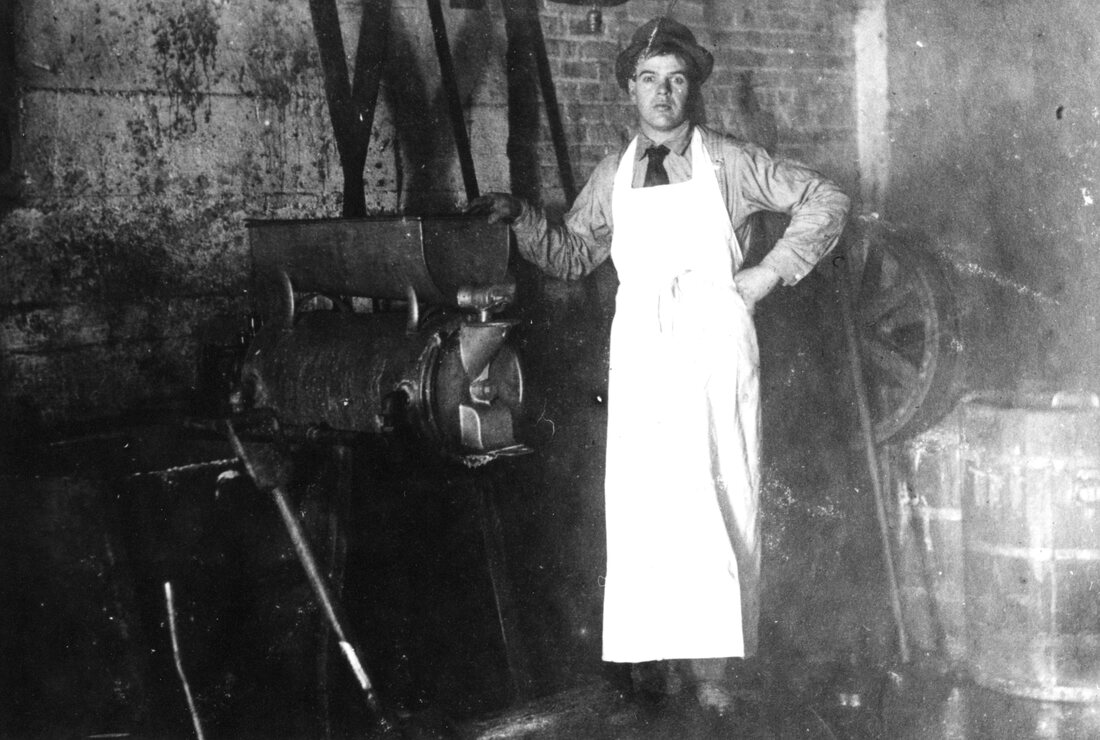

While teaching at the Utah School for the Deaf, Libbie became friends with a young man named Thomas Loran Savage, also known as Loran Savage, from Antimony, Utah (Banks & Banks; Roberts, 1994). The residential nature of the school at the time allowed students and staff members to socialize, leading to several weddings between Deaf individuals (Robert, 1994). Loran, born June 18, 1891, was 14 years younger than Libbie. He was an exceptionally athletic student at the Utah School for the Deaf, excelling in basketball. He studied to become a shoemaker at the school (Banks & Banks).

On July 25, 1917, Libbie and Loran Savage married in Panguitch, Utah. They eventually relocated to Flagstaff, Arizona, where he founded his shoe repair business. Libbie resigned from her teaching career. They had no children. Libbie adored her nieces and nephews (Banks & Banks).

Loran and Libbie worked well together in their shoe repair business. The entire town held Libbie and her husband in high regard, according to Banks & Banks. They were happy "in their constant companionship until her last illness, which, however, did not abate her sweet cheerfulness nor his loving devotion" (Banks & Banks).

Loran and Libbie worked well together in their shoe repair business. The entire town held Libbie and her husband in high regard, according to Banks & Banks. They were happy "in their constant companionship until her last illness, which, however, did not abate her sweet cheerfulness nor his loving devotion" (Banks & Banks).

After fourteen years of marriage, Libbie died of cancer on September 25, 1931, at the age of 57. Everyone who knew her recognized her as having a bright and attractive personality (Banks & Banks). Similarly, her nieces and nephews saw "Aunt Lib" as a cheerful and accomplished woman. They also commented, "With a quick wit and a sense of humor, she never let her deafness prevent her from enjoying life and achieving success." Her dedication to her nieces and nephews was legendary" (Banks & Banks).

A vehicle accident north of Cedar City, Utah, claimed the lives of Loran and his mother, Caroline King Savage, three years after Libbie's death (Banks & Banks). Loran was only 43 years old when this happened.

A vehicle accident north of Cedar City, Utah, claimed the lives of Loran and his mother, Caroline King Savage, three years after Libbie's death (Banks & Banks). Loran was only 43 years old when this happened.

The administrators of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind (USDB) proposed naming the new Deaf school on the USDB campus in Springville, Utah, in honor of Elizabeth DeLong. They were inspired to do so after reading her biography, written by Jodi Becker Kinner, which is available on the Better Days 2020 website.

After receiving approval from the Utah State Board of Education and the USDB Advisory Council, the Utah School for the Deaf announced the opening of a new Deaf school in Springville, Utah, in October 2019. The school is named the "Elizabeth DeLong School of the Deaf," in honor of Elizabeth DeLong, also known as "Libbie." The school opened on January 6, 2020, with a new name and identity. This is a wonderful way to carry on her legacy. The early Utah suffrage effort inspired Libbie to pursue her academic, political, and spiritual goals. She achieved several significant milestones, including becoming the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, making her a trailblazer. The new school, named in her honor, is a fitting tribute to her legacy, as she smiles down on us from across the rainbow.

After receiving approval from the Utah State Board of Education and the USDB Advisory Council, the Utah School for the Deaf announced the opening of a new Deaf school in Springville, Utah, in October 2019. The school is named the "Elizabeth DeLong School of the Deaf," in honor of Elizabeth DeLong, also known as "Libbie." The school opened on January 6, 2020, with a new name and identity. This is a wonderful way to carry on her legacy. The early Utah suffrage effort inspired Libbie to pursue her academic, political, and spiritual goals. She achieved several significant milestones, including becoming the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, making her a trailblazer. The new school, named in her honor, is a fitting tribute to her legacy, as she smiles down on us from across the rainbow.

Note

Thomas C. Clark, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, November 13, 2008.

References

"A Sunday School Organized for the Deaf Mutes." The Daily Enquirer, February 11, 1892. Transcribed and proofread by David Grow, Aug. 2006. http://jared.pratt-family.org/orson_family_histories/laron_pratt_organization.html

Banks, Gladys W. & Banks, Douglas W. "The DeLong Family Saga."

"DeLong and Clark with Driggs to Gallaudet." The Ogden Standard, September 15, 1897.

"Delong and Clark on Gallaudet Buff and Blue." Ogden Standard, June 19, 1901.

Evans, David S. “A Silent World in the Intermountain West: Records from the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind: 1884-1941.” A thesis presented to the Department of History: Utah State University. 1999.

“From the Minutes.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 10 (Summer 1963): 4 & 5.

Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866-1957, "Elizabeth DeLong: B.A., 1902." http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/45785

Historical Events & Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf, February 11, 1992.

Historical Record Book 4 of the Branch for the Deaf, 1941-1945. https://www.utahdeafhistory.com/uploads/5/4/2/6/5426987/ogden_deaf_branch_minutes_1941_-_1945.pdf

Kinner, Jodi Becker. Elizabeth DeLong School of the Deaf. Utah School for the Deaf. https://www.usdb.org/programs/deaf-and-hard-of-hearing/deaf-south-region/

“Locals.” The Buff and Blue, vol. 10, no. 1 (October 1901), p. 29.

“NAD History.” https://www.nad.org/about-us/nad-history/

Roberts, Elaine M. “The Early History of the Utah School for the Deaf and Its influence in the Development of a Cohesive Deaf Society in Utah, circa. 1884 – 1905.” A thesis presented to the Department of History: Brigham Young University. August 1994.

“This Week in 19th Amendment History: Agatha Tiegel Hanson.” (October 17, 1959). https://library.arlingtonva.us/2019/10/14/this-week-in-19th-amendment-history-agatha-tiegel-hanson/

UAD’s First Convention Minutes: 1909 Minutes.

"USDB." Ogden Standard, May 8, 1897.

Banks, Gladys W. & Banks, Douglas W. "The DeLong Family Saga."

"DeLong and Clark with Driggs to Gallaudet." The Ogden Standard, September 15, 1897.

"Delong and Clark on Gallaudet Buff and Blue." Ogden Standard, June 19, 1901.

Evans, David S. “A Silent World in the Intermountain West: Records from the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind: 1884-1941.” A thesis presented to the Department of History: Utah State University. 1999.

“From the Minutes.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 10 (Summer 1963): 4 & 5.

Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866-1957, "Elizabeth DeLong: B.A., 1902." http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/45785

Historical Events & Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf, February 11, 1992.

Historical Record Book 4 of the Branch for the Deaf, 1941-1945. https://www.utahdeafhistory.com/uploads/5/4/2/6/5426987/ogden_deaf_branch_minutes_1941_-_1945.pdf

Kinner, Jodi Becker. Elizabeth DeLong School of the Deaf. Utah School for the Deaf. https://www.usdb.org/programs/deaf-and-hard-of-hearing/deaf-south-region/

“Locals.” The Buff and Blue, vol. 10, no. 1 (October 1901), p. 29.

“NAD History.” https://www.nad.org/about-us/nad-history/

Roberts, Elaine M. “The Early History of the Utah School for the Deaf and Its influence in the Development of a Cohesive Deaf Society in Utah, circa. 1884 – 1905.” A thesis presented to the Department of History: Brigham Young University. August 1994.

“This Week in 19th Amendment History: Agatha Tiegel Hanson.” (October 17, 1959). https://library.arlingtonva.us/2019/10/14/this-week-in-19th-amendment-history-agatha-tiegel-hanson/

UAD’s First Convention Minutes: 1909 Minutes.

"USDB." Ogden Standard, May 8, 1897.

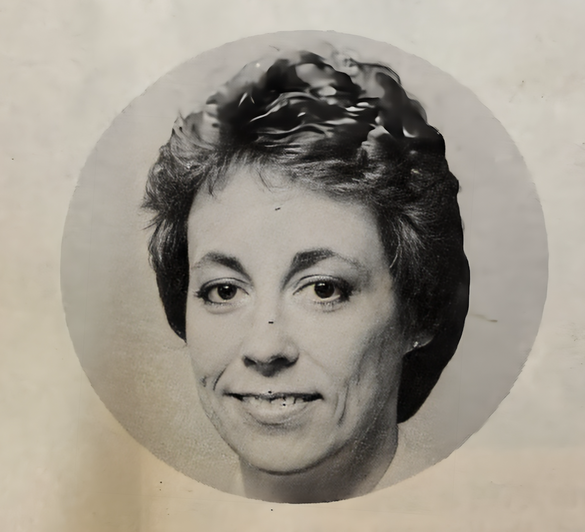

Elsie M. Christiansen, Community Leader

In 1907, Elsie M. Christiansen graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf and immediately began her journey of dedication and passion. She taught history and social studies at the school, served as a houseparent at Driggs Hall, an all-girls dormitory, and played an important role at the Utah School for the Deaf. Her involvement in various capacities at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, the Utah School for the Deaf, and the Utah Association of the Deaf, showcased her as a dedicated community leader who made significant contributions to the Utah Deaf community. Elsie's 28-year service as a branch clerk at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, and her unique position as the first and only Deaf woman in the country to serve as a church clerk, are testaments to her unwavering commitment.

Elsie M. Christiansen was born on June 24, 1884, in Riverton, Utah, to parents Niels John Johanssen-Christiansen and Ellen Stark (Obituaries, December 25, 1972). She was most likely born deaf. According to a family legend, Elsie hurt her eardrums when she jumped on a bed to play and fell off. As a result, her condition was determined to be irreversible (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

According to sources close to her, Elsie was a dedicated professional and a warm and caring individual. She diligently maintained her physique and cleanliness, and her residences were always impeccably neat and clean. Her lovely, thick head of hair that reached her waist and could be wrapped six times around her head was a testament to her personal care. Her family remembers her teaching every family member to say "please" and "thank you," a small but significant detail that reflects her warmth and personal touch (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

Elsie enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, in 1906. However, she only stayed for a year. Before enrolling, she likely attended a public school near her home.

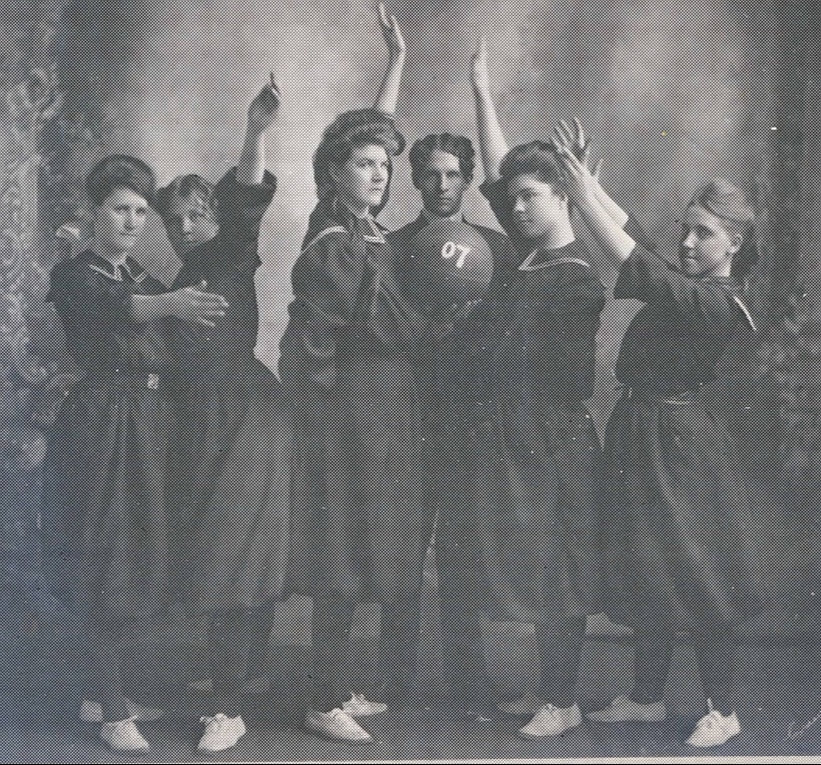

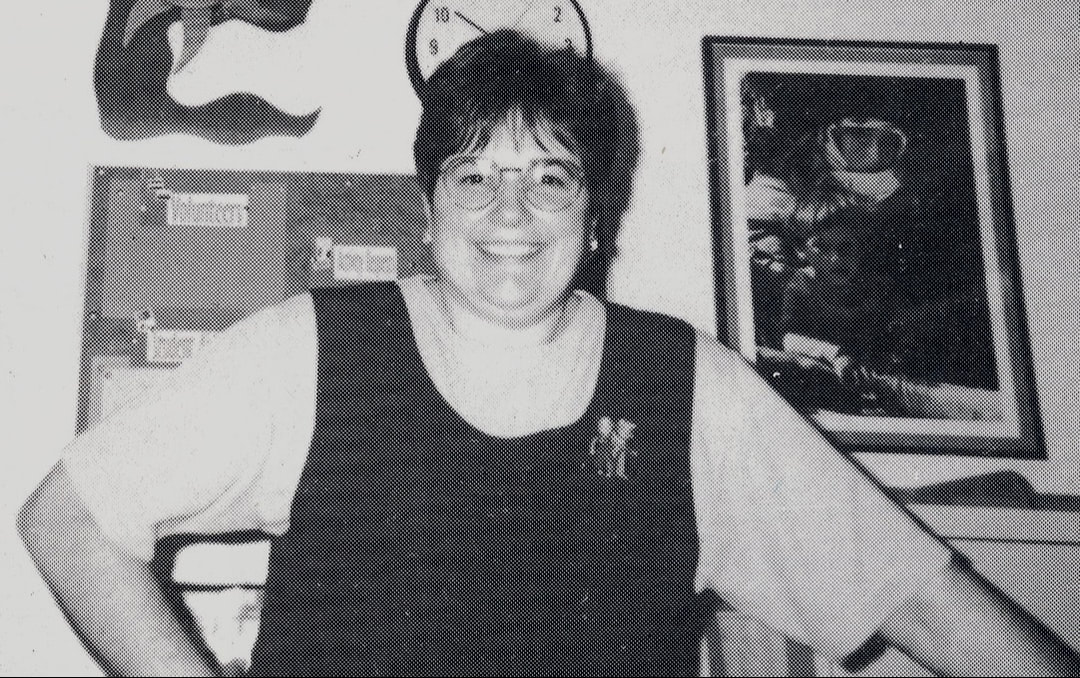

During her senior year in 1907, Elsie joined the school's girls' basketball team. Her height was another advantage; she was 5'10". She graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf the same year, in 1907 (Public Documents: State of Utah, Part 2 1907–1908).

According to sources close to her, Elsie was a dedicated professional and a warm and caring individual. She diligently maintained her physique and cleanliness, and her residences were always impeccably neat and clean. Her lovely, thick head of hair that reached her waist and could be wrapped six times around her head was a testament to her personal care. Her family remembers her teaching every family member to say "please" and "thank you," a small but significant detail that reflects her warmth and personal touch (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

Elsie enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, in 1906. However, she only stayed for a year. Before enrolling, she likely attended a public school near her home.

During her senior year in 1907, Elsie joined the school's girls' basketball team. Her height was another advantage; she was 5'10". She graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf the same year, in 1907 (Public Documents: State of Utah, Part 2 1907–1908).

After graduating, Elsie moved to Lents, Oregon (Tenth Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of Utah, June 30, 1914). Unlike her two classmates, Mary Woolslayer and Emma Emmertson, who both attended the University of Utah, there is no evidence that Elsie did as well. However, Elsie's family believes she attended college (Anne Leahy, interview with Carol Lenichek on October 27, 2011).

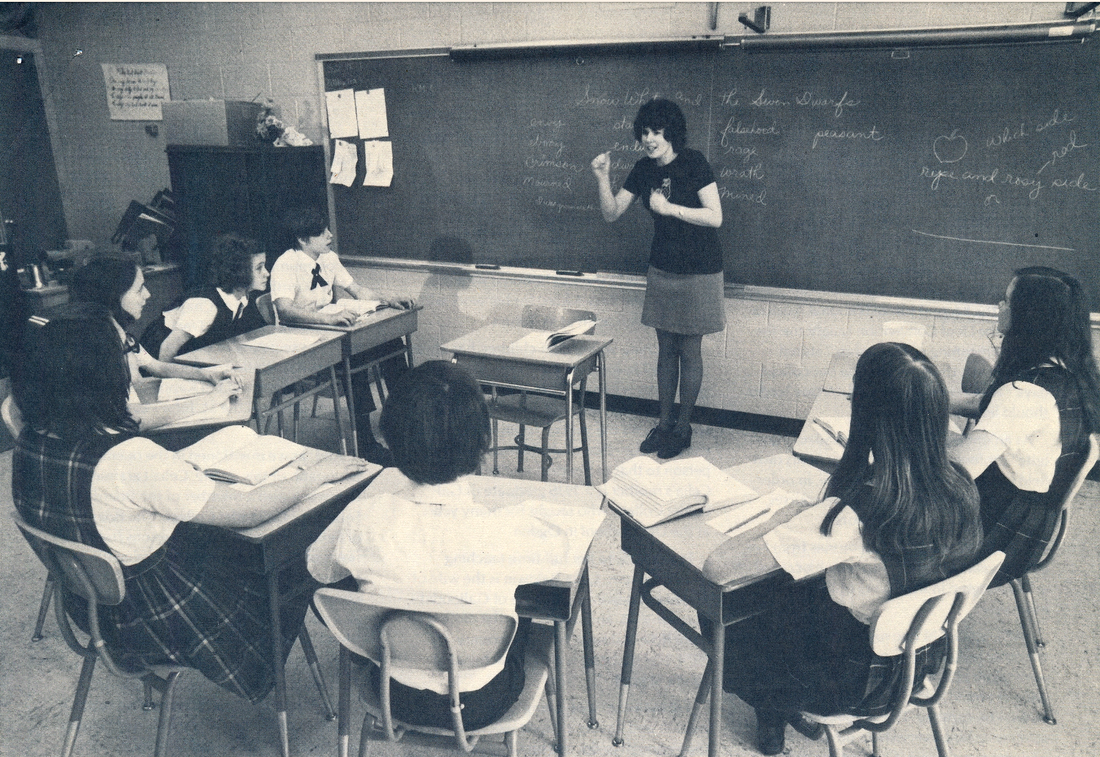

In 1911, Elizabeth DeLong, the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf and a Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, left to pursue a business opportunity. After her departure, Elsie, a high school graduate, replaced her. Elsie taught history and social studies at the school. Notably, at that time, the Utah School for the Deaf did not mandate that all teachers hold a college degree; a high school diploma was considered sufficient.

When houseparents became integral to the Utah School for the Deaf, Elsie became a houseparent at Driggs Hall, a girls' dormitory. Elsie worked as an ironing supervisor at the laundry, directing high school girls to iron boys' shirts and pajamas. Marion Brown West, a 1949 graduate of USD, recognized Elsie as a strict yet fair housemother. Marion Brown recalled Elsie making the girls iron their bed sheets when she felt it was unnecessary (Marion Brown West, personal communication, September 30, 2011). In addition, Elsie's family remembers her teaching every family member to say "please" and "thank you" (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

In 1911, Elizabeth DeLong, the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf and a Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, left to pursue a business opportunity. After her departure, Elsie, a high school graduate, replaced her. Elsie taught history and social studies at the school. Notably, at that time, the Utah School for the Deaf did not mandate that all teachers hold a college degree; a high school diploma was considered sufficient.

When houseparents became integral to the Utah School for the Deaf, Elsie became a houseparent at Driggs Hall, a girls' dormitory. Elsie worked as an ironing supervisor at the laundry, directing high school girls to iron boys' shirts and pajamas. Marion Brown West, a 1949 graduate of USD, recognized Elsie as a strict yet fair housemother. Marion Brown recalled Elsie making the girls iron their bed sheets when she felt it was unnecessary (Marion Brown West, personal communication, September 30, 2011). In addition, Elsie's family remembers her teaching every family member to say "please" and "thank you" (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

Elsie served in various roles at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, the Utah School for the Deaf, and the Utah Association of the Deaf. She was an outstanding community leader who achieved much for Deaf causes.

Elsie was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, she held several positions and worked closely with Max W. Woodbury, the branch president. In 1907, Max, a teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, was appointed as the assistant superintendent of the Sunday School at the Ogden 4th Ward, while Elsie became a secretary. By 1911, Max had become the superintendent of the Sunday School and Elsie his assistant. In 1912, Max and Elsie wrote to President Joseph F. Smith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, explaining the challenges faced by the 4th Ward Sunday School for the Deaf, and requested a dedicated place of worship for Deaf members. A second letter, signed by many older Deaf members, reiterated this request. In addition, Max and Elsie had two meetings with the Church's Presidency to discuss these concerns. Their request was eventually granted (Ogden Branch of the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-45).

On February 14, 1917, the Ogden Branch for the Deaf was formed and established as an independent branch of the Ogden Stake after President Smith dedicated it. Max was sustained as branch president, and Elsie as branch clerk and secretary (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945; Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf - Compiled February 11, 1992).

Elsie was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, she held several positions and worked closely with Max W. Woodbury, the branch president. In 1907, Max, a teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, was appointed as the assistant superintendent of the Sunday School at the Ogden 4th Ward, while Elsie became a secretary. By 1911, Max had become the superintendent of the Sunday School and Elsie his assistant. In 1912, Max and Elsie wrote to President Joseph F. Smith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, explaining the challenges faced by the 4th Ward Sunday School for the Deaf, and requested a dedicated place of worship for Deaf members. A second letter, signed by many older Deaf members, reiterated this request. In addition, Max and Elsie had two meetings with the Church's Presidency to discuss these concerns. Their request was eventually granted (Ogden Branch of the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-45).

On February 14, 1917, the Ogden Branch for the Deaf was formed and established as an independent branch of the Ogden Stake after President Smith dedicated it. Max was sustained as branch president, and Elsie as branch clerk and secretary (Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945; Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf - Compiled February 11, 1992).

Elsie was the president of the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association for thirteen years, from 1917 to 1930. She also served as a class teacher and branch clerk for twenty-eight years, from 1917 to 1945. In addition to these roles, she was a great leader, teacher, and a talented writer.

Elsie was the first and only Deaf woman in the country to serve as a church clerk. Her records were meticulously preserved, and her handwriting was clear. She was always competent and willing to provide needed information, as evidenced in the Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945.

Elsie was the first and only Deaf woman in the country to serve as a church clerk. Her records were meticulously preserved, and her handwriting was clear. She was always competent and willing to provide needed information, as evidenced in the Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941-1945.

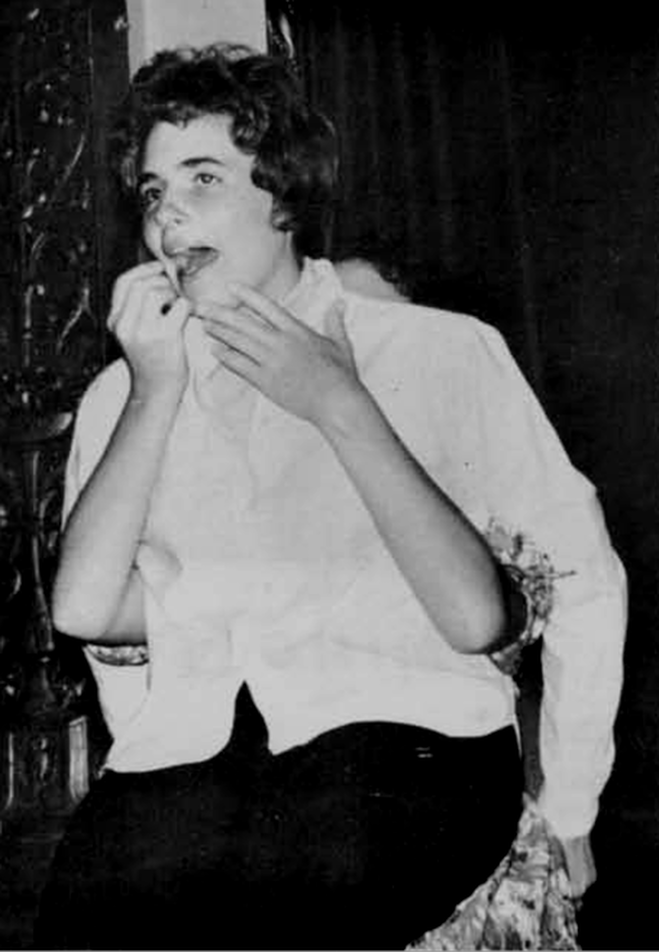

In 1920, Elsie worked as an assistant to Arthur Wenger, the director of theater for the Utah School for the Deaf. The Park Literary Society at the school organized a highly ambitious and successful theatrical production, which was the most extensive effort ever undertaken by Deaf students. The play, "The House of Rimmon," was based on the Bible. Upon request, it was performed once at the school chapel and Salt Lake City's East High School. The performances had no admission fee, and the audience reacted enthusiastically. Moreover, the play played a significant role in helping the general public recognize the abilities of Deaf individuals (White, The Silent Worker, June 1920; Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921; UAD Bulletin, Summer 1964).

In 1934, Elsie, who couldn't drive, purchased a black vehicle. She relied on a Deaf man named Ezra Christensen, who had a facial disfigurement, to drive her. Some sources mention the man's name as "Ethan," but after reviewing certain images, it seems more likely that his name was "Ezra Christensen." Ezra would drive Elsie to Salt Lake City, Utah, so she could occasionally visit her mother while living in Ogden. Elise and Ezra were friends (Anne Leahy, October 27, 2011, personal interview with Carol Lenichek).

In the mid-1950s, Elsie retired from the Utah School for the Deaf. She lived in Salt Lake City, Utah, with her sister, probably Olive, and attended the Salt Lake Branch for the Deaf located at 700 South and 800 East. According to property records, Elsie might have bought the family home in Rose Park with her sister, Olive. The address was 1149 South 200 West in Salt Lake City. The house was later demolished to build a highway (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

In the mid-1950s, Elsie retired from the Utah School for the Deaf. She lived in Salt Lake City, Utah, with her sister, probably Olive, and attended the Salt Lake Branch for the Deaf located at 700 South and 800 East. According to property records, Elsie might have bought the family home in Rose Park with her sister, Olive. The address was 1149 South 200 West in Salt Lake City. The house was later demolished to build a highway (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

In 1961, Elsie was chosen by the State of Utah Department of Welfare and the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to conduct interviews in the Salt Lake area on behalf of the Utah Association of the Deaf. She went door to door in the fall of 1961, asking Deaf individuals aged 55 or older to complete a questionnaire for the Utah Study of the Aged Deaf. Kate Orr Keeley, another Deaf woman, assisted her by driving her around. Various government and private agencies had previously spent significant resources studying issues related to aging and older people, but no one had considered the unique problems faced by the elderly Deaf population in Utah. As a result, the Utah Association of the Deaf requested this group to participate in this groundbreaking research (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, Fall 1961).

Elsie never married. According to Elsie's sister, she was very refined. Elsie never dated because she didn't feel like she fit entirely into the Deaf community. She also didn't feel like she could marry a hearing man because she thought her identity was "half and half" (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

It was a cherished family memory that whenever they visited Aunt Elsie, she always served them fresh, cold milk and peaches (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

Elsie passed away of natural causes on December 23, 1972, at the age of 88, in a nursing facility in Salt Lake City, Utah (Obituaries, December 25, 1972).

Elsie never married. According to Elsie's sister, she was very refined. Elsie never dated because she didn't feel like she fit entirely into the Deaf community. She also didn't feel like she could marry a hearing man because she thought her identity was "half and half" (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

It was a cherished family memory that whenever they visited Aunt Elsie, she always served them fresh, cold milk and peaches (Anne Leahy, personal interview with Carol Lenichek, October 27, 2011).

Elsie passed away of natural causes on December 23, 1972, at the age of 88, in a nursing facility in Salt Lake City, Utah (Obituaries, December 25, 1972).

Notes

Carol Lenichek, interview by Anne Leahy, October 27, 2011.

Marion Brown West, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, September 30, 2011.

Marion Brown West, e-mail message to Jodi Becker Kinner, September 30, 2011.

References

Christensen, Elsie. Ogden Branch for the Deaf Historical Record Book 1941 – 1945.

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the convention of American instructors of the deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, vol. VIL, Washington, D.C.: Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf, 1911.http://books.google.com/books?id=d8AJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA455&lpg=PA455&dq=Elsie+Christiansen,+utah+and+deaf&source=bl&ots=ovSqzoQyv4&sig=0BXfmLY9_R5wE_G1LSU4KUbTUDc&hl=en&ei=_VdyTqSYJ8GlsQKSuPTCCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&sqi=2&ved=0CDgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Elsie%20Christiansen%2C%20utah%20and%20deaf&f=false

“Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf,” February 11, 1992.

"Obituary: Elsie M. Christiansen.” The Deseret News, December 25, 1972. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=YQ0pAAAAIBAJ&sjid=n4UDAAAAIBAJ&pg=7028,6501950

Occupation of Graduates: Utah School for the Deaf. Salt Lake City: The Arrow Press Tribune-Reporter Printing Co, June 30, 1914. http://books.google.com/books?id=-ghQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA376&lpg=PA376&dq=Emma++Emmertson+utah++deaf&source=bl&ots=RrbNznbx_l&sig=EAiSF433vQTRKrE2coS3SBMs92w&hl=en&ei=-ZJzTrzPLoHgiAKY0720Ag&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFgQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=Emma%20%20Emmertson%20utah%20%20deaf&f=false

Report of the Coal Mine Inspector for the State of Utah: For the Years 1907 and 1908. Salt Lake City Tribune-Reporter PTG. Co, 1909. http://books.google.com/books?id=om8K4RfEq0YC&pg=PP7&dq=Public+Documents:+State+of+Utah,+Part+2+1907-1908&hl=en&sa=X&ei=TAmUUN-sI-SbjALCgoGACQ&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAA

Sanderson, Robert G. "Old age study gets rolling." UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 4 (Fall 1961): 4.

“Those Were The Days…” UAD Bulletin, vol. 3, no. 4. (Summer 1964): 5.

White, Bob. "Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32 no. 7 (April 1920): 186.

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the convention of American instructors of the deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, vol. VIL, Washington, D.C.: Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf, 1911.http://books.google.com/books?id=d8AJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA455&lpg=PA455&dq=Elsie+Christiansen,+utah+and+deaf&source=bl&ots=ovSqzoQyv4&sig=0BXfmLY9_R5wE_G1LSU4KUbTUDc&hl=en&ei=_VdyTqSYJ8GlsQKSuPTCCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&sqi=2&ved=0CDgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Elsie%20Christiansen%2C%20utah%20and%20deaf&f=false

“Historical Events and Persons Involved Branch for the Deaf,” February 11, 1992.

"Obituary: Elsie M. Christiansen.” The Deseret News, December 25, 1972. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=YQ0pAAAAIBAJ&sjid=n4UDAAAAIBAJ&pg=7028,6501950

Occupation of Graduates: Utah School for the Deaf. Salt Lake City: The Arrow Press Tribune-Reporter Printing Co, June 30, 1914. http://books.google.com/books?id=-ghQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA376&lpg=PA376&dq=Emma++Emmertson+utah++deaf&source=bl&ots=RrbNznbx_l&sig=EAiSF433vQTRKrE2coS3SBMs92w&hl=en&ei=-ZJzTrzPLoHgiAKY0720Ag&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFgQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=Emma%20%20Emmertson%20utah%20%20deaf&f=false

Report of the Coal Mine Inspector for the State of Utah: For the Years 1907 and 1908. Salt Lake City Tribune-Reporter PTG. Co, 1909. http://books.google.com/books?id=om8K4RfEq0YC&pg=PP7&dq=Public+Documents:+State+of+Utah,+Part+2+1907-1908&hl=en&sa=X&ei=TAmUUN-sI-SbjALCgoGACQ&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAA

Sanderson, Robert G. "Old age study gets rolling." UAD Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 4 (Fall 1961): 4.

“Those Were The Days…” UAD Bulletin, vol. 3, no. 4. (Summer 1964): 5.

White, Bob. "Notes and Comments from the Land of the Mormons.” The Silent Worker, vol. 32 no. 7 (April 1920): 186.

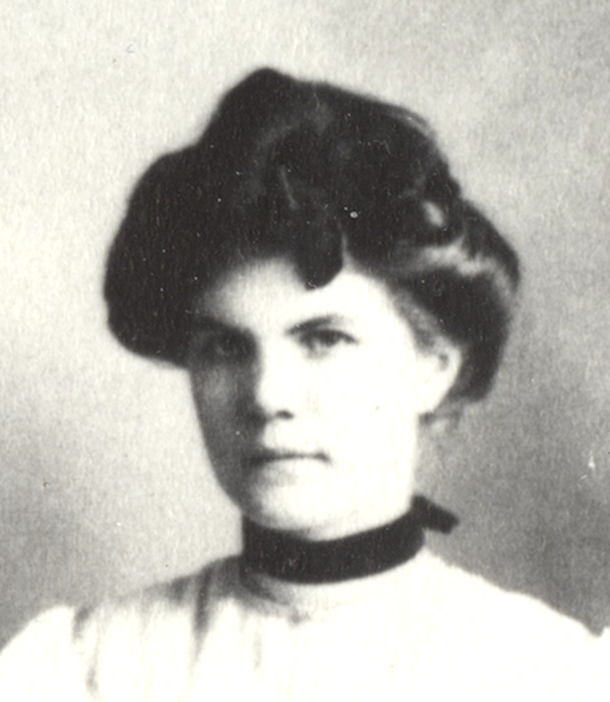

Mary Wooslayer, Resilient Leader

Mary Wooslayer was the first Deaf female student at the University of Utah, enrolling in 1910 and graduating with a bachelor's degree in physical education in 1916. Despite the lack of a sign language interpreter, she attended lectures and successfully passed all her classes, earning more credits than many of her classmates due to her hard work and determination. She was the first in a class of around a hundred students studying home science. After graduating, Mary worked as a Deaf school teacher in Texas, Virginia, and Kentucky.

Mary Woolslayer was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on January 5, 1887. Her family later relocated to Utah, and she grew up in Bountiful, Utah (UAD Bulletin, March 1984). Her father, Samuel Wullschleger (or 'Woolslayer'), passed away, leaving her mother, Anna Maria (Marianne Haller), as an impoverished widow. The date and location of Samuel's death are unknown (Mary Woolslayer Photograph Collection, 1890).

Despite the early challenges of being unable to speak or hear due to diphtheria, Mary Woolslayer's resilience shone through. She attended the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) in Ogden, Utah, starting in 1898 and graduated in 1907. In seventh grade, she wrote and published an article titled "Good Books" in the Utah Eagle magazine, emphasizing the value of reading good books.

Despite the early challenges of being unable to speak or hear due to diphtheria, Mary Woolslayer's resilience shone through. She attended the Utah School for the Deaf (USD) in Ogden, Utah, starting in 1898 and graduated in 1907. In seventh grade, she wrote and published an article titled "Good Books" in the Utah Eagle magazine, emphasizing the value of reading good books.

GOOD BOOKS

If we read good books, we shall certainly obtain many benefits from them. They will assist us to live good, true lives and also give us far higher and nobler ambitions in life.

If we read poor, or bad books, we shall not be helped by them, but harmed, because they do not teach us what is right.

They will help to improve our language if we read them and make our minds brighter and broader. Read! Read! Good books for they will do you much good and will be useful.

We will be capable of doing well in the world from the effects of reading good books. Anyone who never reads good books will be sorry for it later in life.

Abraham Lincoln had never been to school, but he had spent much of time reading good books. This made him a great man (Woolslayer, The Utah Eagle, May 15, 1904). If we read good books, we shall certainly obtain many benefits from them. They will assist us to live good, true lives and also give us far higher and nobler ambitions in life.

If we read poor, or bad books, we shall not be helped by them, but harmed, because they do not teach us what is right.

They will help to improve our language if we read them and make our minds brighter and broader. Read! Read! Good books for they will do you much good and will be useful.

We will be capable of doing well in the world from the effects of reading good books. Anyone who never reads good books will be sorry for it later in life.

Abraham Lincoln had never been to school, but he had spent much of time reading good books. This made him a great man (Woolslayer, The Utah Eagle, May 15, 1904).

If we read poor, or bad books, we shall not be helped by them, but harmed, because they do not teach us what is right.

They will help to improve our language if we read them and make our minds brighter and broader. Read! Read! Good books for they will do you much good and will be useful.

We will be capable of doing well in the world from the effects of reading good books. Anyone who never reads good books will be sorry for it later in life.

Abraham Lincoln had never been to school, but he had spent much of time reading good books. This made him a great man (Woolslayer, The Utah Eagle, May 15, 1904). If we read good books, we shall certainly obtain many benefits from them. They will assist us to live good, true lives and also give us far higher and nobler ambitions in life.

If we read poor, or bad books, we shall not be helped by them, but harmed, because they do not teach us what is right.

They will help to improve our language if we read them and make our minds brighter and broader. Read! Read! Good books for they will do you much good and will be useful.

We will be capable of doing well in the world from the effects of reading good books. Anyone who never reads good books will be sorry for it later in life.

Abraham Lincoln had never been to school, but he had spent much of time reading good books. This made him a great man (Woolslayer, The Utah Eagle, May 15, 1904).

Mary Woolslayer made history when she enrolled at the University of Utah in 1910 as its first Deaf student. Her graduation with a bachelor's degree in physical education in 1916 (Mary Woolslayer's University of Utah transcript, 1916) was a testament to her courage and determination. Her coursework was more extensive and covered more departments than any other university student, and she excelled in domestic science, ranking first in a class of nearly 100 students (Utah Digital Newspaper, January 10, 1914).

While Mary was a student, she was sponsored by Maud May Babcock, who was a member of the Utah School for the Deaf Board of Trustees and a faculty member at the University of Utah (Mary Woolslayer Photograph Collection, 1890). Mary worked part-time in laundry services over the summer to pay her way through college, and during the winter, she received board and lodging with a private family (Utah Digital Newspaper, January 10, 1914). Mary was likely motivated to pursue her education at the University of Utah due to the early emphasis on advancing education and employment opportunities for women in Utah, as well as her connection to Maud May Babcock.

Maud May Babcock gave Mary Woolslayer a photograph with the message, "With much love to Mary." Yours sincerely, Maul May Babcock." Mary attended the University of Utah under Miss Babcock's sponsorship and graduated with the Class of 1916. Photo courtesy of J. Willard Marriot Library The University of Utah

In 1915, a year before she graduated from the University of Utah, Mary served as a secretary for the Utah Association of the Deaf. Afterward, she taught in Texas, Virginia, and Kentucky (UAD Bulletin, March 1984). In 1916, she was hired as a physical education director for girls at the Texas School for the Deaf (Fay, 1916).

On the evening of Washington's Birthday, February 21, 1920, Mary Woolslayer's commitment to the Utah Deaf community was further demonstrated when she joined the Salt Lake City Division No. 56 of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf. This significant event took place during a banquet hosted at the Newhouse Hotel, marking her active involvement in the society (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920; Golden Anniversary: Salt Lake City Division No. 56 National Fraternal Society of the Deaf 1916-1966).

On the evening of Washington's Birthday, February 21, 1920, Mary Woolslayer's commitment to the Utah Deaf community was further demonstrated when she joined the Salt Lake City Division No. 56 of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf. This significant event took place during a banquet hosted at the Newhouse Hotel, marking her active involvement in the society (White, The Silent Worker, April 1920; Golden Anniversary: Salt Lake City Division No. 56 National Fraternal Society of the Deaf 1916-1966).

In 1922, Mary was hired as a physical education instructor for girls at the Kentucky School for the Deaf in Danville, Kentucky (Fosdick, 1856). She taught at the school for 40 years. During her adult years, she traveled extensively and lived a very happy and productive life. She never married (Mary Woolslayer Photograph Collection, 1890).

Later in life, Mary returned to her home state of Utah, living at the Heritage Place Retirement Home in Bountiful for her final years. She passed away in Bountiful, Utah, on March 21, 1984, at the age of 97 (Mary Woolslayer Photograph Collection, 1890; UAD Bulletin, March 1984).

Later in life, Mary returned to her home state of Utah, living at the Heritage Place Retirement Home in Bountiful for her final years. She passed away in Bountiful, Utah, on March 21, 1984, at the age of 97 (Mary Woolslayer Photograph Collection, 1890; UAD Bulletin, March 1984).

References

“Deaf Mute Working Her Way Through University Leads in her classes, adept in many arts.” Utah Digital Newspaper, January 10, 1914. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/tgm14&CISOPTR=49750&CISOSHOW=50001

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. American Annals of the Deaf.Washington, D.C.: Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf, 1916. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZqlKAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA461&lpg=PA461&dq=Mary+Woolslayer+utah+deaf&source=bl&ots=lmFN_lM-J8&sig=GoVttIsw68vn5YTT0kn21OCyGow&hl=en&ei=-X5zTuOLFa6EsALR68yLBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CDsQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Mary%20Woolslayer%20utah%20deaf&f=false

Occupation of Graduates: Utah School for the Deaf. Salt Lake City: The Arrow Press Tribune-Reporter Printing Co, June 30, 1914. http://books.google.com/books?id=-ghQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA376&lpg=PA376&dq=Emma++Emmertson+utah++deaf&source=bl&ots=RrbNznbx_l&sig=EAiSF433vQTRKrE2coS3SBMs92w&hl=en&ei=-ZJzTrzPLoHgiAKY0720Ag&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFgQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=Emma%20%20Emmertson%20utah%20%20deaf&f=false

Fosdick, C.P. "Centennial History of the Kentucky School for the Deaf, Danville, Kentucky." Kentucky Standard, 1923.http://kdl.kyvl.org/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=kyetexts;cc=kyetexts;q1=Mary%20Woolslayer;rgn=full%20text;idno=b92-138-29331425;didno=b92-138-29331425;view=pdf;seq=52;passterms=1

Mary Woolslayer Photograph Collection. (1890). J. Willard Marriot Library, University of Utah. Collection Number UU_P0669.

Mary Woolslayer’s University of Utah Transcript, 1916.

"News of Note: Mary Woolslayer."UAD Bulletin, vol. 7, No. 10 (March 1984): 5.

Wooslayer, Mary. Good Books. The Utah Eagle, vol. XV, #7 (May 15, 1904): 107.

Fay, Edward Allen. Organ of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. American Annals of the Deaf.Washington, D.C.: Conference of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf, 1916. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZqlKAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA461&lpg=PA461&dq=Mary+Woolslayer+utah+deaf&source=bl&ots=lmFN_lM-J8&sig=GoVttIsw68vn5YTT0kn21OCyGow&hl=en&ei=-X5zTuOLFa6EsALR68yLBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CDsQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Mary%20Woolslayer%20utah%20deaf&f=false

Occupation of Graduates: Utah School for the Deaf. Salt Lake City: The Arrow Press Tribune-Reporter Printing Co, June 30, 1914. http://books.google.com/books?id=-ghQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA376&lpg=PA376&dq=Emma++Emmertson+utah++deaf&source=bl&ots=RrbNznbx_l&sig=EAiSF433vQTRKrE2coS3SBMs92w&hl=en&ei=-ZJzTrzPLoHgiAKY0720Ag&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFgQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=Emma%20%20Emmertson%20utah%20%20deaf&f=false

Fosdick, C.P. "Centennial History of the Kentucky School for the Deaf, Danville, Kentucky." Kentucky Standard, 1923.http://kdl.kyvl.org/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=kyetexts;cc=kyetexts;q1=Mary%20Woolslayer;rgn=full%20text;idno=b92-138-29331425;didno=b92-138-29331425;view=pdf;seq=52;passterms=1

Mary Woolslayer Photograph Collection. (1890). J. Willard Marriot Library, University of Utah. Collection Number UU_P0669.

Mary Woolslayer’s University of Utah Transcript, 1916.

"News of Note: Mary Woolslayer."UAD Bulletin, vol. 7, No. 10 (March 1984): 5.

Wooslayer, Mary. Good Books. The Utah Eagle, vol. XV, #7 (May 15, 1904): 107.

Emma M. Emmertson, Suffragette Leader

Emma M. Emmertson enrolled in the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, at the age of 15 and graduated in 1907. She was the second Deaf student at the University of Utah, a testament to her determination and courage. Emma started her studies at the university in 1911 and earned a degree in kindergarten teaching in 1917. After obtaining her bachelor's degree, Emma briefly taught in Salt Lake City, Utah, before moving to Wyoming to teach at the Wyoming School for the Deaf. Emma was also a suffragette during the Women's Rights Movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Emma M. Emmertson was born on June 27, 1888, in Huntsville, Utah, to Emmert Emmertsen and Petra Sorensen. She was originally from Ogden, Utah.

Emma enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, when she was 15. During her senior year in 1907, she joined the girls' basketball team and graduated in the same year.

Emma was the second Deaf student to attend the University of Utah, following Mary Woolslayer, a 1907 graduate from the Utah School for the Deaf and the first Deaf female student. She began her studies in 1911 and received her bachelor's degree in kindergarten teaching in 1917 (Emma M. Emmertson's University of Utah Transcript, 1917).

Emma enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, when she was 15. During her senior year in 1907, she joined the girls' basketball team and graduated in the same year.

Emma was the second Deaf student to attend the University of Utah, following Mary Woolslayer, a 1907 graduate from the Utah School for the Deaf and the first Deaf female student. She began her studies in 1911 and received her bachelor's degree in kindergarten teaching in 1917 (Emma M. Emmertson's University of Utah Transcript, 1917).

Emma briefly taught in Salt Lake City, Utah, after earning her bachelor's degree (Utah Digital Newspapers, January 10, 1914). She then relocated to Wyoming to teach at the Wyoming School for the Deaf (Utah Digital Newspapers, January 10, 1914).

At the age of 30, Emma married a deaf man named Carl Emil Jorgensen, an Ogden native, on August 8, 1918, in Farmington, Utah.

Emma, as her grandson Don Jorgenson II, revealed in an interview with Carolyn Jorgenson, was a suffragette who actively participated in the Women's Suffrage Movement from the late 19th to the early 20th century. This movement was a significant social and political campaign that sought to secure voting rights for women. Emma's granddaughter, Kristan Jorgensen, also described Emma as a very strong woman on FamilySearch.org.

Notably, Utah's women's suffrage campaign, a local movement crucial in influencing history, had a big impact on Emma's involvement in it. This movement, which successfully granted women the right to vote in Utah in 1870, also considerably influenced Elizabeth DeLong, the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf. Emma was inspired by the courage and determination of these women, which fueled her own activism. If you want to learn more about women's suffrage in Utah, including in the Deaf and hearing communities, you can visit the 'Outstanding Contributions in the Early History of Utah's Deaf and Non-Deaf Women' webpage on this website.

Emma passed away on December 3, 1969, at 81. She is buried in Sacramento, California.

At the age of 30, Emma married a deaf man named Carl Emil Jorgensen, an Ogden native, on August 8, 1918, in Farmington, Utah.

Emma, as her grandson Don Jorgenson II, revealed in an interview with Carolyn Jorgenson, was a suffragette who actively participated in the Women's Suffrage Movement from the late 19th to the early 20th century. This movement was a significant social and political campaign that sought to secure voting rights for women. Emma's granddaughter, Kristan Jorgensen, also described Emma as a very strong woman on FamilySearch.org.

Notably, Utah's women's suffrage campaign, a local movement crucial in influencing history, had a big impact on Emma's involvement in it. This movement, which successfully granted women the right to vote in Utah in 1870, also considerably influenced Elizabeth DeLong, the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf. Emma was inspired by the courage and determination of these women, which fueled her own activism. If you want to learn more about women's suffrage in Utah, including in the Deaf and hearing communities, you can visit the 'Outstanding Contributions in the Early History of Utah's Deaf and Non-Deaf Women' webpage on this website.

Emma passed away on December 3, 1969, at 81. She is buried in Sacramento, California.

Notes

Carolyn Jorgenson, wife of Don Jorgenson II, interview by Anne Leahy, September 30, 2011.

Kristan Jorgensen, personal communication, December 7, 2017.

Kristan Jorgensen, personal communication, December 7, 2017.

References

"Deaf Mute Working Her Way Through University Leads in her classes, adept in many arts." Utah Digital Newspaper. (January 10, 1914). http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/tgm14&CISOPTR=49750&CISOSHOW=50001

Emma M. Emmertson’s University of Utah Transcript, 1917.

Emma M. Emmertson’s University of Utah Transcript, 1917.

Justina Wooldridge Keeley,

Community Advocate Leader

Justina Wooldridge Keeley, a member of Salt Lake City Division No. 56 of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf (NFSD), demonstrated remarkable perseverance. She learned about NFSD in 1916 while visiting her home state of Missouri, and upon returning to Utah, she shared information about an insurance organization owned and operated by Deaf individuals. The Salt Lake City Division No. 56 was established on October 24, 1916. Justina's discovery was bittersweet because, for 35 years, the NFSD denied women, including Justina, full membership and admission to the NFSD. Despite these challenges, women, including Justina, persevered. It was not until 1951, during the NFSD convention in Chicago, Illinois, that women like Justina received regular insurance membership.

Justina Wooldridge Keeley, born on December 7, 1888, in East Lynne, Missouri, was the daughter of Robert A. Wooldridge and Mary F. Clement. The cause of her deafness remains unknown. She was a member of the Methodist Church, a faith that played a significant role in her life.

Justina married a Deaf man named Joseph Goshen Keeley on December 24, 1912, in Salt Lake City, Utah. Joseph's siblings, Alfred Charles Jr. and Kate Orr Keeley, were also deaf, and Kate never married. Their deafness was attributed to their mother, Viola Goshen, using quinine during her pregnancies. Back then, doctors were not aware of the side effects of quinine.

Justina married a Deaf man named Joseph Goshen Keeley on December 24, 1912, in Salt Lake City, Utah. Joseph's siblings, Alfred Charles Jr. and Kate Orr Keeley, were also deaf, and Kate never married. Their deafness was attributed to their mother, Viola Goshen, using quinine during her pregnancies. Back then, doctors were not aware of the side effects of quinine.

In 1891, Joseph enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf, which was located at the University of Deseret (later renamed the University of Utah) in Salt Lake City, Utah. Joseph's deaf siblings, Alfred and Kate, enrolled at the Utah School for the Deaf when it moved to Ogden, Utah, in 1896. Their father, Alfred Charles Keeley, owned Keeley's Ice Cream Company in Salt Lake City, Utah. After graduating from Gallaudet College in 1916, Alfred worked in his father's business (Alfred Charles Keeley Jr., Gallaudet University Alumni Cards: 1866–1962).

Justina's contributions to the Utah Association of the Deaf were not just significant, they were widely recognized. In 1936, she was honored with a lifetime membership in the association, a testament to her dedication and impact (UAD Bulletin, June 1973). She held positions as a board member and secretary, further solidifying her role in the association and her recognition in the community.

Justina, a pivotal figure in the history of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, later joined the Salt Lake City Division No. 56. She discovered NFSD, an insurance organization owned and operated by Deaf individuals, during a visit to Missouri, which was a turning point for her. After returning to Salt Lake City, Utah, she shared the news and inspired others, including Melville John Matheis, a Deaf resident of Utah. Intrigued by the organization, he made a personal journey to Chicago to gain a deeper understanding of its operations. Impressed by what he saw, he became an NFSD member on August 1, 1916. The Salt Lake City Division No. 56 was established on October 24, 1916, by eight men with the assistance of Grand Secretary-Treasurer Francis P. Gibson (UAD Bulletin, Summer, 1966; Walker, 1966). Justina's discovery was bittersweet because, for 35 years, the NFSD denied women, including Justina, full membership and admission to the NFSD. In 1951, at the convention in Chicago, Illinois, the NFSD made a historic decision to grant women regular insurance membership and admission. This decision was a significant milestone in the organization's history, emphasizing the importance of gender inclusion in NFSD (Records of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, 1900–2006).

Justina, a pivotal figure in the history of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, later joined the Salt Lake City Division No. 56. She discovered NFSD, an insurance organization owned and operated by Deaf individuals, during a visit to Missouri, which was a turning point for her. After returning to Salt Lake City, Utah, she shared the news and inspired others, including Melville John Matheis, a Deaf resident of Utah. Intrigued by the organization, he made a personal journey to Chicago to gain a deeper understanding of its operations. Impressed by what he saw, he became an NFSD member on August 1, 1916. The Salt Lake City Division No. 56 was established on October 24, 1916, by eight men with the assistance of Grand Secretary-Treasurer Francis P. Gibson (UAD Bulletin, Summer, 1966; Walker, 1966). Justina's discovery was bittersweet because, for 35 years, the NFSD denied women, including Justina, full membership and admission to the NFSD. In 1951, at the convention in Chicago, Illinois, the NFSD made a historic decision to grant women regular insurance membership and admission. This decision was a significant milestone in the organization's history, emphasizing the importance of gender inclusion in NFSD (Records of the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, 1900–2006).

Justina passed away in a Salt Lake hospital due to natural causes on April 6, 1973, and she is buried in Wasatch Lawn Memorial Park in Salt Lake City, Utah, alongside her husband (UAD Bulletin, June 1973).

References

“Alfred Charles Keeley Jr.: B.A., 1916.” Gallaudet University Alumni Cards, 1866-1957. http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/46239

Gallaudet University Archives. “Records of National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, 1900-2006. MSS 163." http://www.gallaudet.edu/Library_Deaf_Collections_and_Archives/Collections/Manuscript_Collection/MSS_163.html

"Justina W. Keeley." UAD Bulletin, Vol. 8, No. 3 (June 1973): 5.

Gallaudet University Archives. “Records of National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, 1900-2006. MSS 163." http://www.gallaudet.edu/Library_Deaf_Collections_and_Archives/Collections/Manuscript_Collection/MSS_163.html

"Justina W. Keeley." UAD Bulletin, Vol. 8, No. 3 (June 1973): 5.

Afton Curtis Burdett, Educational Leader

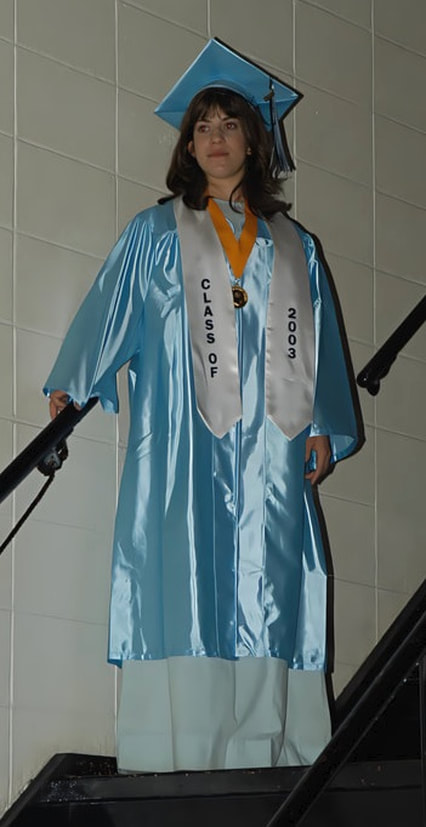

After Afton Curtis Burdett graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1933, she attended Gallaudet College. While at Gallaudet, she worked as a maid for the college president, Percival Hall. Afton later dropped out of Gallaudet to marry Kenneth C. Burdett, who was also a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf and Gallaudet College. With her family and work responsibilities, Afton returned to college and eventually became the first Deaf student to graduate from Weber State College (later renamed Weber State University) in 1956, earning an Associate of Science degree. She continued her studies at Utah State University, where she became the first Deaf person to earn a bachelor's degree with honors. On June 6, 1959, she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Elementary Education with an English minor, leaving a significant mark in the field of deaf education.

Afton Curtis Burdett was the first child and only daughter of Guy A. Curtis and Agnes Rasmussen. She was born on September 14, 1914, in Ferron City, Utah. As a young child, she suffered from an ear infection, which led to permanent hearing loss. Her parents sought medical treatment for her in Salt Lake City, Utah. The physicians were unable to help at the time. When Afton turned six, her family moved to Ogden, Utah, so that she could attend the Utah School for the Deaf. While at the school, she lived in a dorm, but her family remained nearby.

Afton was a brilliant student who excelled in various subjects, such as reading, math, sign language, and ballet. She even went on to teach dance to others. She also picked up woodworking skills in a manual training class and eventually crafted a beautiful cedar chest (A Family Remembered: The Family of Hans Peter Rasmussen and Anna Maria Andersen).