Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream

for an Equal Deaf Education System

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2014

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2014

Author's Note

As a parent of two Deaf children, my passion for deaf education comes from my personal journey. My father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, also sparked my interest and shared with me the history of deaf education in Utah, including its oral and mainstreaming impact. This inspired me to meticulously document the controversial events of that era. If it weren't for him, I wouldn't be able to advocate for my kids without knowing the history. My studies at the Gallaudet School Social Work Program further deepened my understanding of the complexities of education, legislation, and policy. Moreover, my role on the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind has truly empowered me to advocate for my children and others in Utah who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled. This platform has given me the strength and voice to make a difference.

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

As an advocate for deaf education in Utah, I have personally witnessed firsthand the inequality in the deaf education system. The Utah School for the Deaf has long been criticized for its favoritism towards oral education, a stance that has led to numerous conflicts between the oral and sign language departments in the dual-track and two-track programs. While working on Utah Deaf History, I and other ASL/English bilingual supporters found ourselves battling with Steven W. Noyce, the superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, who was a staunch advocate for the oral movement. During this period, our Deaf Education Advocate, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, penned an article in the 1992 UAD Bulletin titled "My Dream." This article was an essential piece in the history of deaf education, as it outlined a more inclusive and balanced approach to education that could provide solutions for both oral and sign language departments. However, it wasn't until 2016, under the hybrid program, that this vision finally became a reality, as explained on this webpage.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

As an advocate for deaf education in Utah, I have personally witnessed firsthand the inequality in the deaf education system. The Utah School for the Deaf has long been criticized for its favoritism towards oral education, a stance that has led to numerous conflicts between the oral and sign language departments in the dual-track and two-track programs. While working on Utah Deaf History, I and other ASL/English bilingual supporters found ourselves battling with Steven W. Noyce, the superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, who was a staunch advocate for the oral movement. During this period, our Deaf Education Advocate, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, penned an article in the 1992 UAD Bulletin titled "My Dream." This article was an essential piece in the history of deaf education, as it outlined a more inclusive and balanced approach to education that could provide solutions for both oral and sign language departments. However, it wasn't until 2016, under the hybrid program, that this vision finally became a reality, as explained on this webpage.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Acknowledgment

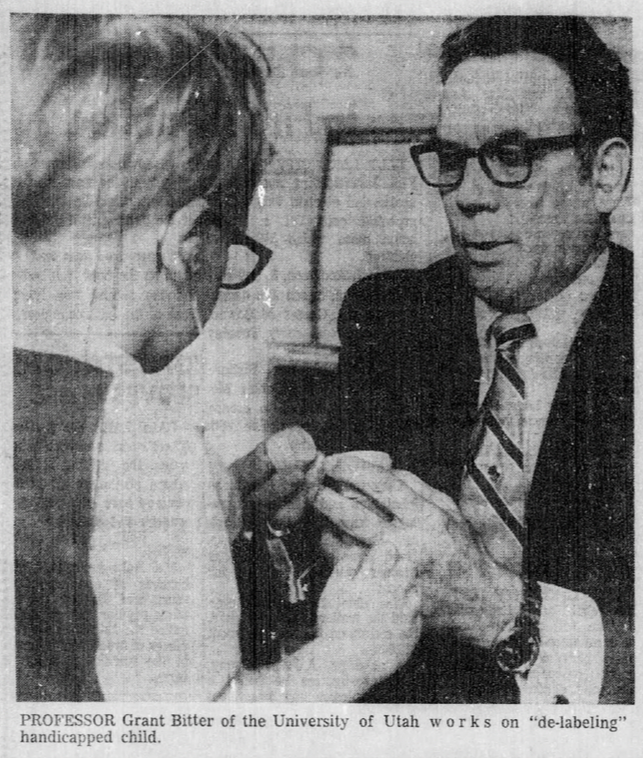

I wanted to thank my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, for sharing about the dual-track and two-track programs at the Utah School for the Deaf, as well as the impact of the "Y" system. As the father of two Deaf children, Deanne and Duane, his first-hand experience within the system was a valuable source of information. Because I was so fascinated by those segregation programs at Ogden's residential campus while documenting historical events, I dove more into them, but I could not find the word "Y" system Ken had told me about in any documents for validation. My search led me to Dr. Grant B. Bitter's papers that he donated to the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah. His paper played a crucial role in validating the existence of the "Y" system. One of his papers stated, "Thus there would be a true dual system rather than the present "Y" system that forces all parents to place their children under oral programs until the 6th grade or 7th grade year." The date on which Dr. Bitter wrote his paper about this program is unknown. It appears that Dr. Bitter penned his paper in the early 1970s to prepare for the meeting that followed the replacement of the dual-track program with a two-track program, which eliminated the "Y" system in 1970. So, I'm grateful to Ken for telling me about the "Y" system and how it affected many families. Otherwise, we would not have known about it or understood what "Y" means when we ran across Dr. Bitter's paper.

When Steven W. Noyce became superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind in 2009, his support for oral and mainstream education raised concerns within the Utah Deaf community. As a parent of Deaf children, I was worried that Steven Noyce would carry Dr. Grant B. Bitter's legacy by promoting oral education and mainstreaming all Deaf children in Utah. On November 3, 2009, I raised this issue with him and Associate Superintendent Jennifer Howell. I knew that Steven, a former student of Dr. Bitter's Oral Training Program at the University of Utah and a long-time employee at the Utah School for the Deaf, was fully aware of the controversy between oral and sign language. To protect the ASL/English bilingual program, I detailed Dr. Grant B. Bitter's controversial history of oral and mainstreaming advocacy, as well as the profound impact of the dual-track and two-track programs at the Utah School for the Deaf. I recommended providing an equal balance between the Listening and Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual options for families of Deaf children. I also requested preventive measures to avoid the recurrence of similar issues. Steven acknowledged the accuracy of the information and said, "This is the most accurate paper I have ever read." This recognition of the paper's credibility underscores the importance of our advocacy efforts. I owe a debt of gratitude to my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, for sharing this critical history with me. His insights and knowledge have proven invaluable in our advocacy efforts for deaf education. Without his help, we couldn't have opposed the oral agenda.

Thank you, Ken!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Thank you, Ken!

Jodi Becker Kinner

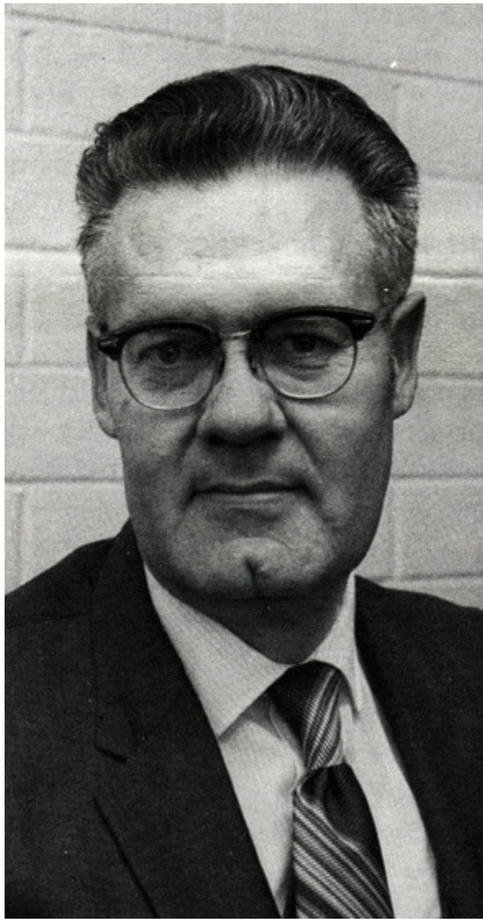

Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

the Father of Mainstreaming

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter, who opposed anyone who stood in the way of his goals of promoting oral and mainstream education, has formally requested the job removal of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, both respected advocates for sign language. He believed they were interfering with his mission. Additionally, he expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, feeling it did not align with his educational goals. He also asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected committee chairperson, to resign because she invited representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he saw as a shift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf, in the face of Dr. Bitter's opposition, demonstrated remarkable resilience, marking a significant turning point in our history and inspiring others with their strength and determination.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. His journey began at the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked as a teacher and curriculum coordinator. His passion for education led him to become a director and professor in the Teacher Training Program, where he focused primarily on oral education under the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. Dr. Bitter also served as the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

The Implementation of the Dual-Track Program,

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

In the fall of 1962, the Utah Deaf community was surprised by the revolutionary changes at the Utah School for the Deaf, which introduced the dual-track program, also commonly known as the "Y" system. The unexpected change had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children, evoking a sense of empathy within the community. The Utah Association of the Deaf, which advocated for sign language, was unaware that the Utah Council for the Deaf had spearheaded the change, advocating for speech-based instruction and successfully pushing for its implementation at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962). It is believed that Dr. Bitter was a member of this council. The dual-track program provided an oral program in one department and a simultaneous communication program in another department, which was later replaced by a combined system. However, the dual-track policy mandated that all Deaf children begin with the oral program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Gannon, 1981). The Utah State Board of Education, a key player in educational policy, approved this policy reform on June 14, 1962, with endorsement from the Special Study Committee on Deaf Education (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). The newly hired superintendent, Robert W. Tegeder, accepted the parents' proposals and initiated changes to the school system (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter, 1962; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). This new program not only affected the lives of Deaf children but also their families.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

As a result of the "Y" system's implementation, the Utah School for the Deaf had to undergo significant changes. The school had to hire more oral teachers and establish speech as the primary mode of communication, shifting the focus of the learning environment. The dual-track program initially placed all elementary school students in the oral department, transferring them to the simultaneous communication department only if they failed in the oral program. This approach was based on the belief that early development of oral skills was crucial for Deaf students, with sign language learning considered a secondary focus. The change in focus and the increased hiring of oral teachers had a significant impact on the school's learning environment, altering its dynamics and atmosphere (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, some changes were made at the Utah School for the Deaf without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were surprised to find out about the changes. These changes caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy.

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, some changes were made at the Utah School for the Deaf without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were surprised to find out about the changes. These changes caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy.

Did You Know?

In 1959, 97% of the Utah School for the Deaf teachers were members of the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf (Christopulos, The Utah Eagle, November 1960).

The Implementation

of the The Two-Track Program

at the Utah School for the Deaf

of the The Two-Track Program

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Following the 1962 protest against social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a steadfast advocate for oral and mainstream education, and his oral supporters suspected that the Utah Association of the Deaf had organized the student strike. The Utah State Board of Education conducted an investigation but found no evidence of any connection between the students and the Utah Association for the Deaf (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). In the face of societal segregation, the simultaneous communication students demonstrated their unwavering determination and courage by staging their own protests.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

Another round of students' acts of resistance during the 1969 walkout protest against the continued enforcement of "Y" social segregation in the dual-track program was a defining moment in history, echoing the 1962 student protest at the Utah School for the Deaf. Despite not achieving the desired results, they found new ways to voice their discontent. Some sign language students boldly crossed the oral department hallway, while others took the simultaneous communication department route. This act of defiance broke the "Y" system rule, which had designated these spaces as 'off-limits' in order to maintain a 'clean' communication environment. Students even confronted their oral teachers, accusing them of oppression and dominance (Raymond Monson, personal communication, November 9, 2010). For nearly a decade, the Utah Association for the Deaf, in collaboration with the Parent-Teacher-Student Association, comprised supportive parents who advocated for sign language and fought against the "Y" system. Despite years of dismissal and opposition, their unwavering determination and resilience in the face of social segregation are truly admirable.

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, when faced with a challenging situation, sought assistance from his boss, Dr. Jay J. Campbell. Dr. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Campbell, a sign language interpreter and the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, had been a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community. Motivated by his concern for the welfare of Deaf children, he took the initiative to create the two-track program, a new instrument system that replaced the "Y" system (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Campbell, 1977; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). His dedication and commitment to the cause are genuinely inspiring.

Ned C. Wheeler, who became deaf at the age of 13 and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1933, was the chair of the USDB Governor's Advisory Council. He proposed the "two-track program" in response to various events, including Dr. Campbell's proposal, student strikes in 1962 and 1969, and opposition from the Parent Teacher Student Association to the "Y" system policy. On December 28, 1970, the Utah State Board of Education authorized a new policy, paving the way for the Utah School for the Deaf to operate a two-track program with choices, eliminating the "Y" system. This program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011, Recommendations on Policy for the Utah School for the Deaf, 1970; Deseret News, December 29, 1970).

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

Another round of students' acts of resistance during the 1969 walkout protest against the continued enforcement of "Y" social segregation in the dual-track program was a defining moment in history, echoing the 1962 student protest at the Utah School for the Deaf. Despite not achieving the desired results, they found new ways to voice their discontent. Some sign language students boldly crossed the oral department hallway, while others took the simultaneous communication department route. This act of defiance broke the "Y" system rule, which had designated these spaces as 'off-limits' in order to maintain a 'clean' communication environment. Students even confronted their oral teachers, accusing them of oppression and dominance (Raymond Monson, personal communication, November 9, 2010). For nearly a decade, the Utah Association for the Deaf, in collaboration with the Parent-Teacher-Student Association, comprised supportive parents who advocated for sign language and fought against the "Y" system. Despite years of dismissal and opposition, their unwavering determination and resilience in the face of social segregation are truly admirable.

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, when faced with a challenging situation, sought assistance from his boss, Dr. Jay J. Campbell. Dr. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Campbell, a sign language interpreter and the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, had been a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community. Motivated by his concern for the welfare of Deaf children, he took the initiative to create the two-track program, a new instrument system that replaced the "Y" system (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Campbell, 1977; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). His dedication and commitment to the cause are genuinely inspiring.

Ned C. Wheeler, who became deaf at the age of 13 and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1933, was the chair of the USDB Governor's Advisory Council. He proposed the "two-track program" in response to various events, including Dr. Campbell's proposal, student strikes in 1962 and 1969, and opposition from the Parent Teacher Student Association to the "Y" system policy. On December 28, 1970, the Utah State Board of Education authorized a new policy, paving the way for the Utah School for the Deaf to operate a two-track program with choices, eliminating the "Y" system. This program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011, Recommendations on Policy for the Utah School for the Deaf, 1970; Deseret News, December 29, 1970).

However, while supervising the Utah School for the Deaf, Dr. Campbell noticed that parents were often unaware of their children's educational and communication options (Campbell, 1977). Despite the Utah State Board of Education releasing policies in 1970, 1977, and 1998, the Utah School for the Deaf's Communication Guidelines did not provide parents with a wide range of choices. This lack of clarity resulted in ineffective placement tactics due to the prevalent oral bias. On April 14, 1977, Dr. Campbell presented his 200-page study report concerning the Utah School for the Deaf at the Utah State Board of Education. He also sought to improve the school's education system through more equitable evaluation and placement methods. However, Dr. Bitter, a professor at the University of Utah at the time, vehemently opposed Dr. Campbell's research, accusing it of containing falsehoods and drawing unfounded conclusions about the University of Utah's Teacher Oral Training Program and educational programs across the state (G.B. Bitter, personal communication, March 6, 1978). The presentation was heated, with over 300 parents supporting the oral method and applauding Dr. Bitter and Peter Viahos, an Ogden attorney and father of a Deaf daughter, as they presented their arguments (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977).

A group of parents, under the influence of Dr. Bitter, petitioned the Utah State Board of Education. They sought to suspend Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study, citing its inconclusive nature. Also, dissatisfied with his research findings, they demanded his termination (Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). Approximately 50 to 60 Deaf individuals attended the meeting (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Those who attended the meeting were Ned C. Wheeler, W. David Mortensen, Lloyd Perkins, Dennis Platt, Kenneth L. Kinner, and others.

Dr. Bitter, a spokesperson for the oral advocates, presented Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, with three options:

Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot's response to Dr. Bitter's appeal sparked a firestorm of tension. The Deaf group fiercely opposed the State Board's decision to reassign Dr. Campbell within the Utah State Office of Education. Their dissatisfaction was intense, leading them to express their protest by stomping their feet on the floor. In his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter described the scene as highly emotional and chaotic, prompting him to consider leaving the room. Concerned about the escalating situation, Dr. Talbot asked the Deaf community members to leave the room (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Disagreements still exist about what the Deaf people did during the meeting, as different versions of what happened differ.

The Utah State Board of Education accepted Dr. Campbell's report and supporting documentation. However, despite the controversy surrounding his analysis, which included data from independent researchers, they disregarded all of his recommendations (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977). This decision had consequences, as Dr. Campbell's plan crumbled down, including a two-year study to improve education through fair assessment and placement procedures. His plan was buried and forgotten (Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

Dr. Bitter, a spokesperson for the oral advocates, presented Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, with three options:

- Removing Dr. Campbell from his position;

- Assigning him to another position; or

- Requesting a grand jury investigation into the evidence demonstrating how oral Deaf individuals were intimidated by some of the state's programs (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot's response to Dr. Bitter's appeal sparked a firestorm of tension. The Deaf group fiercely opposed the State Board's decision to reassign Dr. Campbell within the Utah State Office of Education. Their dissatisfaction was intense, leading them to express their protest by stomping their feet on the floor. In his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter described the scene as highly emotional and chaotic, prompting him to consider leaving the room. Concerned about the escalating situation, Dr. Talbot asked the Deaf community members to leave the room (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Disagreements still exist about what the Deaf people did during the meeting, as different versions of what happened differ.

The Utah State Board of Education accepted Dr. Campbell's report and supporting documentation. However, despite the controversy surrounding his analysis, which included data from independent researchers, they disregarded all of his recommendations (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977). This decision had consequences, as Dr. Campbell's plan crumbled down, including a two-year study to improve education through fair assessment and placement procedures. His plan was buried and forgotten (Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

A Conflict Between Two Giants,

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson and Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

and the Impact of Bias Towards Oral Education

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson and Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

and the Impact of Bias Towards Oral Education

The conflict between Dr. Robert G. Sanderson and Dr. Grant B. Bitter, two prominent figures in the field of deaf education, is a significant historical event. Dr. Bitter's clear bias towards oral education has had a profound impact on the field, making it a compelling subject of study.

Despite the availability of the Total Communication Program at the Utah School for the Deaf, many parents remained unaware of its existence. Dr. Grant B. Bitter convened 'An Oral Demonstration Panel' at the University of Utah, which recruited local oral Deaf adults to participate. Deaf individuals, Dr. Robert Sanderson, W. David Mortensen, C. Roy Cochran, Kenneth L. Kinner, and other Deaf individuals who supported sign language were in attendance, as were other hearing attendees, where the oral Deaf individuals shared their experiences growing up in an oral environment with the audience. After the oral demonstration, Dr. Bitter announced the start of a question-and-answer session. Dr. Sanderson, a respected figure in the Deaf community, rose to his feet and inquired, 'Have you heard the other side of the program?' Dr. Bitter abruptly ended the meeting without answering his question or providing an explanation (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011).

The animosity between Dr. Grant B. Bitter and Dr. Robert G. Sanderson was both intense and visible. Dr. Bitter's 'Oral Demonstration Panels' were not just academic exercises but a platform for him to assert his beliefs. When Dr. Sanderson and his interpreter, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, were in the audience, Dr. Bitter deliberately talked fast, aiming to throw Dr. Sanderson off. Beth Ann, determined to ensure Dr. Sanderson had access to the information and could have his voice heard, signed as quickly as she could. Despite Dr. Bitter's challenge, Dr. Sanderson managed to grasp the content and actively participated while focusing on his interpreter (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

The conflict involving Dr. Bitter had a significant impact on oral deaf education. Legia Johnson, a parent and oral teacher, expressed concern about Dr. Bitter's decision to involve her daughter, Colleen Johnson Jones, in his demonstration panels. Dr. Bitter used Legia's daughter to represent his own, as she spoke better than his daughter, who was also named Colleen. This led to Legia resigning from her teaching position at the oral extension program of the Utah School for the Deaf. Legia's resignation was a clear protest against the use of her daughter as a prop in Dr. Bitter's demonstrations, revealing deep divisions within the oral group (Lisa Richards, personal communication, April 14, 2009).

Despite the availability of the Total Communication Program at the Utah School for the Deaf, many parents remained unaware of its existence. Dr. Grant B. Bitter convened 'An Oral Demonstration Panel' at the University of Utah, which recruited local oral Deaf adults to participate. Deaf individuals, Dr. Robert Sanderson, W. David Mortensen, C. Roy Cochran, Kenneth L. Kinner, and other Deaf individuals who supported sign language were in attendance, as were other hearing attendees, where the oral Deaf individuals shared their experiences growing up in an oral environment with the audience. After the oral demonstration, Dr. Bitter announced the start of a question-and-answer session. Dr. Sanderson, a respected figure in the Deaf community, rose to his feet and inquired, 'Have you heard the other side of the program?' Dr. Bitter abruptly ended the meeting without answering his question or providing an explanation (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011).

The animosity between Dr. Grant B. Bitter and Dr. Robert G. Sanderson was both intense and visible. Dr. Bitter's 'Oral Demonstration Panels' were not just academic exercises but a platform for him to assert his beliefs. When Dr. Sanderson and his interpreter, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, were in the audience, Dr. Bitter deliberately talked fast, aiming to throw Dr. Sanderson off. Beth Ann, determined to ensure Dr. Sanderson had access to the information and could have his voice heard, signed as quickly as she could. Despite Dr. Bitter's challenge, Dr. Sanderson managed to grasp the content and actively participated while focusing on his interpreter (Beth Ann Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

The conflict involving Dr. Bitter had a significant impact on oral deaf education. Legia Johnson, a parent and oral teacher, expressed concern about Dr. Bitter's decision to involve her daughter, Colleen Johnson Jones, in his demonstration panels. Dr. Bitter used Legia's daughter to represent his own, as she spoke better than his daughter, who was also named Colleen. This led to Legia resigning from her teaching position at the oral extension program of the Utah School for the Deaf. Legia's resignation was a clear protest against the use of her daughter as a prop in Dr. Bitter's demonstrations, revealing deep divisions within the oral group (Lisa Richards, personal communication, April 14, 2009).

Beth Ann, caught in the middle of their long-standing conflict, shared her experiences at the interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010. She revealed that every time she walked into the room, Dr. Bitter would say he didn't want her at the meeting. Bob said, "Well, she's staying." She witnessed their initial battles, with Bob 'bugging' Dr. Bitter and Dr. Bitter trying to 'bug' back. She also mentioned that during legislative hearings, Dr. Bitter would speak as fast as he could and use big words to challenge her interpreting skills. Yet Beth Ann could keep up with her interpreting job, which infuriated Dr. Bitter. Bob would sit back while Dr. Bitter tried to unsettle him by saying, 'You can read my lips.' Bob, who lost his hearing at age 11 but could speak and read lips, ignored Dr. Bitter and continued to look at Beth Ann while she interpreted. Bob refused to give in to Dr. Bitter's challenges. Beth Ann said it was a constant battle between them. She acknowledged the ongoing conflict between oral and sign language but didn't think it was as vicious as it had been during the Sanderson and Bitter era (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010).

Dr. Sanderson made his position clear on the controversy: He supports parents' right to choose the most suitable educational program for their Deaf children. However, he emphasized that the information provided to parents must be fair and accurate. He stressed the importance of accurate information when making educational decisions and opposed any "inaccurate, biased, or one-sided data" that lacks a research base (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, March 1992).

According to Dr. Jay J. Campbell, the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, a father with a 14-year-old Deaf son expressed concern about his son's limited reading and writing abilities while enrolling in an oral program. Seeking advice, the father met with Dr. Campbell. Dr. Campbell asked the father whether he knew about the Total Communication Program. The father stated that he was unaware of such a program (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). This parental ignorance led Dr. Campbell to realize the need for a brochure explaining both programs and their communication options. Dr. Campbell also stressed the importance of regularly updating this pamphlet based on empirical research results (Campbell, 1977). However, Dr. Bitter strongly opposed the plan, arguing that the total communication system was solely a philosophy and not a valid teaching methodology (Dr. Grant B. Bitter, personal communication, February 4, 1985). Despite Dr. Campbell's efforts, the plan for the informational booklet faced significant obstacles.

Dr. Sanderson made his position clear on the controversy: He supports parents' right to choose the most suitable educational program for their Deaf children. However, he emphasized that the information provided to parents must be fair and accurate. He stressed the importance of accurate information when making educational decisions and opposed any "inaccurate, biased, or one-sided data" that lacks a research base (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, March 1992).

According to Dr. Jay J. Campbell, the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, a father with a 14-year-old Deaf son expressed concern about his son's limited reading and writing abilities while enrolling in an oral program. Seeking advice, the father met with Dr. Campbell. Dr. Campbell asked the father whether he knew about the Total Communication Program. The father stated that he was unaware of such a program (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). This parental ignorance led Dr. Campbell to realize the need for a brochure explaining both programs and their communication options. Dr. Campbell also stressed the importance of regularly updating this pamphlet based on empirical research results (Campbell, 1977). However, Dr. Bitter strongly opposed the plan, arguing that the total communication system was solely a philosophy and not a valid teaching methodology (Dr. Grant B. Bitter, personal communication, February 4, 1985). Despite Dr. Campbell's efforts, the plan for the informational booklet faced significant obstacles.

Dr. Grant B. Bitter Poses Challenges

to the Utah Association for the Deaf

to the Utah Association for the Deaf

Dr. Bitter's challenge to the Utah Association for the Deaf was not a random act but a response to what he perceived as a threat to his position. During the interview with the University of Utah in 1987, Dr. Bitter stated that Dr. Sanderson, who became deaf when he was 11 and grew up in both public school and state school for the deaf, 'knew nothing about school programs, but because he was deaf and an advocate of the Deaf community, he obviously played a vital role as far as the Deaf community was concerned' (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987, p. 30). Dr. Sanderson campaigned politically for sign language and was appointed by the Utah State Office of Education, along with other members of the Utah Association for the Deaf, to committees. Dr. Bitter challenged this, particularly Della Loveridge, a legislator and Deaf community advocate who appointed Dr. Sanderson and other Deaf members to her committee while Dr. Bitter was also on it. Dr. Bitter felt threatened by their committee appointments but denied it in his interview. He believed that his objection constituted a threat to them. At a state committee meeting, Della Loveridge described Dr. Bitter as "emotionally disturbed." Dr. Bitter thought that the Utah Association for the Deaf had too much freedom in the state office of education, where they held their meetings, and requested that Della Loveridge step down as committee chairperson. This sparked a feud against Dr. Bitter (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

Dr. Bitter's interview also shared a dramatic conflict between him and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education and an advocate for the Utah Deaf community, and Dr. Sanderson. Both Dr. Campbell and Dr. Sanderson were part of a committee studying the operations of the Utah School for the Deaf. With the support of 300 parents of Deaf oral children, Dr. Bitter successfully blocked their proposal on how the Utah School for the Deaf should run, as detailed in the 'Dr. Jay J. Campbell's 1977 Comprehensive Study of the Utah School for the Deaf' webpage.

Dr. Frank R. Turk, the national director of the Jr. NAD, collaborated with Dr. Sanderson, who was president of the National Association of the Deaf in the 1960s, in a way that contradicted Dr. Bitter's description of him. He described Dr. Sanderson as an exceptional advocate for education who had a deep understanding of how a Deaf child's K–12 education connects with higher education and eventually leads to desired employment. He strongly advocated for young people with leadership potential and focused on promoting social, educational, economic, and communication equality for Deaf Americans. Dr. Sanderson believed in the importance of socialization in education and advised teachers to encourage students to question their school experience. He urged teachers in public and residential schools to encourage deaf students to ask questions about their school experience. He emphasized that children should learn not only the traditional three R's of reading, writing, and arithmetic but also the importance of socialization. This focus on socialization led to the development of "resourcefulness," which included after-school activities to develop essential life skills such as leadership, empowerment, attitude, discipline, empathy, respect, struggle, humility, initiative, and perseverance. Consequently, the Jr. NAD and SBG organizations were assigned to develop these crucial real-life skills essential for success in school, college, the workplace, career, and community life (Turk, From Oaks to Acorns, 2019).

In a 1982 interview, Dr. Sanderson, a prominent figure in the field of rehabilitation services, who had completed his one-year professorship at Gallaudet College holding the Powrie V. Doctor Chair of Deaf Studies, was asked about his thoughts on total communication and its impact on a child's development. He emphasized the importance of using all available means of communication to help deaf children develop. He stated, "Communication is life. It starts at birth and is a lifelong process. If a baby is suspected to be deaf, I believe that the communication process should begin as soon as the baby can focus his eyes. I would be very concerned that parents understand this. If the process is delayed, a deaf child just cannot catch up—too much is lost. It doesn't matter if the child later learns language or learns how to read lips; he still won't be able to catch up." Dr. Sanderson emphasized that effective communication is more important than the communication method, and many boil down to a lack of clear communication. To ensure a child's optimal learning and development, the focus should be on the quality of communication rather than the specific method. Putting too much emphasis on the mode of communication can very quickly turn off the communication process. He explained that total communication refers to using all available means to communicate ideas when a child is ready. Children differ in readiness, receptivity, tolerance, frustration, and responsiveness. While one child may quickly adapt to speech training, another may become frustrated and unresponsive. Therefore, total communication should consider these individual differences. In his opinion, many schools do not incorporate what is known about the psychology of communication (Kent, The Deaf American, 1982, p. 3). As demonstrated by Dr. Sanderson's thoughts during the interview, his life likely took a dramatic turn when he lost his hearing at eleven. His enrollment at the Utah School for the Deaf, where he learned sign language, probably marked a transformative chapter. He likely realized he had a significant advantage in language development over his born-deaf peers with hearing parents with no language access at home. The school also provided him with full access to education, which was a stark contrast to the limited access he had in a public school after his recovery. This difference in educational opportunities likely fueled his advocacy for Deaf children, highlighting the urgency for them to have access to language and education at residential schools. This challenged Dr. Bitter's mission to promote oralism and mainstream education.

During the political dispute between Dr. Sanderson and Dr. Bitter, Hannah P. Lewis, a hearing parent of a grown Deaf son, stated in 1977 that Dr. Sanderson has been a guiding light for the deaf all these years and emphasized the need for his continued support. She said, "I cannot thank him enough for all the help he has given my son throughout his growing-up years." "Thank God for a man like him" (Lewis, Deseret News, November 24, 1977, p. A4). Despite this, Dr. Sanderson and the Utah Association for the Deaf demonstrated remarkable resilience when confronted by Dr. Bitter, marking a significant turning point in their history. This likely explains why the oral supporters secretly implemented the 1962 dual-track program behind their backs without informing them—a strategy that ran successfully without encountering any challenges or controversies, possibly to maintain its dominance. This oral dominance approach at the Utah School for the Deaf continued for more than 50 years until the introduction of the hybrid program, which marked a shift in 2016. Since then, the Utah Association of the Deaf has diligently championed deaf education, actively engaging in every education committee to guarantee their representation in meetings. They also fought relentlessly, eventually passing on the task of continuing the struggle for deaf education equality in Utah to the next generation. The next generation rose to the challenge and established four ASL/English bilingual programs in four regions—Ogden, Salt Lake City, Springville, and St. George. These programs aimed to provide a balanced approach to deaf education, incorporating both American Sign Language and English. They made significant progress, providing a glimpse of the bright future ahead.

Dr. Frank R. Turk, the national director of the Jr. NAD, collaborated with Dr. Sanderson, who was president of the National Association of the Deaf in the 1960s, in a way that contradicted Dr. Bitter's description of him. He described Dr. Sanderson as an exceptional advocate for education who had a deep understanding of how a Deaf child's K–12 education connects with higher education and eventually leads to desired employment. He strongly advocated for young people with leadership potential and focused on promoting social, educational, economic, and communication equality for Deaf Americans. Dr. Sanderson believed in the importance of socialization in education and advised teachers to encourage students to question their school experience. He urged teachers in public and residential schools to encourage deaf students to ask questions about their school experience. He emphasized that children should learn not only the traditional three R's of reading, writing, and arithmetic but also the importance of socialization. This focus on socialization led to the development of "resourcefulness," which included after-school activities to develop essential life skills such as leadership, empowerment, attitude, discipline, empathy, respect, struggle, humility, initiative, and perseverance. Consequently, the Jr. NAD and SBG organizations were assigned to develop these crucial real-life skills essential for success in school, college, the workplace, career, and community life (Turk, From Oaks to Acorns, 2019).

In a 1982 interview, Dr. Sanderson, a prominent figure in the field of rehabilitation services, who had completed his one-year professorship at Gallaudet College holding the Powrie V. Doctor Chair of Deaf Studies, was asked about his thoughts on total communication and its impact on a child's development. He emphasized the importance of using all available means of communication to help deaf children develop. He stated, "Communication is life. It starts at birth and is a lifelong process. If a baby is suspected to be deaf, I believe that the communication process should begin as soon as the baby can focus his eyes. I would be very concerned that parents understand this. If the process is delayed, a deaf child just cannot catch up—too much is lost. It doesn't matter if the child later learns language or learns how to read lips; he still won't be able to catch up." Dr. Sanderson emphasized that effective communication is more important than the communication method, and many boil down to a lack of clear communication. To ensure a child's optimal learning and development, the focus should be on the quality of communication rather than the specific method. Putting too much emphasis on the mode of communication can very quickly turn off the communication process. He explained that total communication refers to using all available means to communicate ideas when a child is ready. Children differ in readiness, receptivity, tolerance, frustration, and responsiveness. While one child may quickly adapt to speech training, another may become frustrated and unresponsive. Therefore, total communication should consider these individual differences. In his opinion, many schools do not incorporate what is known about the psychology of communication (Kent, The Deaf American, 1982, p. 3). As demonstrated by Dr. Sanderson's thoughts during the interview, his life likely took a dramatic turn when he lost his hearing at eleven. His enrollment at the Utah School for the Deaf, where he learned sign language, probably marked a transformative chapter. He likely realized he had a significant advantage in language development over his born-deaf peers with hearing parents with no language access at home. The school also provided him with full access to education, which was a stark contrast to the limited access he had in a public school after his recovery. This difference in educational opportunities likely fueled his advocacy for Deaf children, highlighting the urgency for them to have access to language and education at residential schools. This challenged Dr. Bitter's mission to promote oralism and mainstream education.

During the political dispute between Dr. Sanderson and Dr. Bitter, Hannah P. Lewis, a hearing parent of a grown Deaf son, stated in 1977 that Dr. Sanderson has been a guiding light for the deaf all these years and emphasized the need for his continued support. She said, "I cannot thank him enough for all the help he has given my son throughout his growing-up years." "Thank God for a man like him" (Lewis, Deseret News, November 24, 1977, p. A4). Despite this, Dr. Sanderson and the Utah Association for the Deaf demonstrated remarkable resilience when confronted by Dr. Bitter, marking a significant turning point in their history. This likely explains why the oral supporters secretly implemented the 1962 dual-track program behind their backs without informing them—a strategy that ran successfully without encountering any challenges or controversies, possibly to maintain its dominance. This oral dominance approach at the Utah School for the Deaf continued for more than 50 years until the introduction of the hybrid program, which marked a shift in 2016. Since then, the Utah Association of the Deaf has diligently championed deaf education, actively engaging in every education committee to guarantee their representation in meetings. They also fought relentlessly, eventually passing on the task of continuing the struggle for deaf education equality in Utah to the next generation. The next generation rose to the challenge and established four ASL/English bilingual programs in four regions—Ogden, Salt Lake City, Springville, and St. George. These programs aimed to provide a balanced approach to deaf education, incorporating both American Sign Language and English. They made significant progress, providing a glimpse of the bright future ahead.

A New Parent Infant Program Orientation

is Formed at the Utah School for the Deaf

is Formed at the Utah School for the Deaf

The mental trend of the "Y" system in the two-track program, with prevalent oral bias, persisted. This biased information had a profound impact, limiting the choices parents could make for their Deaf children's education and communication. Although Dr. J. Jay Campbell tried to provide fair information in the 1970s, Dr. Bitter opposed his efforts because he believed that total communication was a concept, not a word, and also a philosophy, not a method (Campbell, 1977; Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, August 20, 1977, p. 25; Bitter, Concern with Deaf Center Paper, 1985). In 2010, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group challenged this biased approach and advocated for unbiased and equal information. Superintendent Steven W. Noyce of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, an oral advocate and former university student of Dr. Bitter, as well as a long-time teacher and school director, created the Parent Infant Program Orientation to provide parents with fair and balanced information. However, parents still had to choose an "either/or" selection between ASL/English bilingual (replaced total communication) or listening and spoken language (replace oral) options for their children's education and communication, which resulted in the expansion of the listening and spoken program because the majority of Deaf children are born to hearing parents.

Deaf student Toni Ekenstam gets auditory training from Steven Noyce, a teacher of the deaf. Toni is taught to lip read and communicate with her own voice, one of several methods used to teach deaf children at the Utah School for the Deaf @ Deseret News, March 8, 1973. Deseret News Photo by Chief Photographer Don Groyston

Jeff W. Pollock, a member of the USDB Advisory Council representing the Utah Deaf community, requested on February 10, 2011, that the Utah School for the Deaf implement the guidelines titled "The National Agenda: Moving Forward on Achieving Educational Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students" to address philosophical, placement, communication, and service delivery biases. One of the members of the Advisory Council wondered if the Deaf National Agenda was solely based on ASL. He clarified that the Deaf National Agenda does not exclusively rely on ASL but instead emphasizes the holistic development of each child, supporting both ASL and spoken language, unlike the current system's "either/or" approach. Jeff then addressed Superintendent Noyce in the eyes and stated that the USD has reverted to the inefficient "Y" system of the last 30–40 years, with an oral OR sign, and is not providing both ASL and LSL to parents who want both options. Superintendent Noyce remained silent about the subject. The "Y" system mental trend in the two-track program with prevalent oral bias persisted until Joel Coleman, superintendent of Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind, and Michelle Tanner, associate superintendent of Utah Schools for the Deaf, took action. Creating the Hybrid Program in 2016 was a significant step towards removing the requirement for parents to choose between the two programs "either/or." Their innovative approach is crucial and brings hope for unbiased and equal information. More information about the hybrid program can be found at the end of this webpage.

Suffice it to say, Dr. Grant B. Bitter was a prominent figure in Utah's oralism and mainstreaming movement, which had a significant impact on deaf education in Utah since 1962, despite the new two-track program and the school's option guidelines. As a result of his efforts, the number of students attending Ogden's residential school for Deaf students decreased, and the quality of education also declined. The mainstreaming approach gained popularity but left many alums heartbroken. Dr. Bitter also had significant power as a parental figure and used it to push for oralism, making it difficult for the Utah Association for the Deaf to challenge him. When the Teacher Training Program in the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah closed in 1986, he retired in 1987 (Bitter, A Summary Report for Tenure, March 15, 1985). Today, the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah offers a Specialization in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program. While the curriculum does include American Sign Language classes, it still places a greater emphasis on listening and spoken language. This reflects the impact that Dr. Bitter, who passed away in 2000, continues to have on deaf education in Utah. To learn more about the evolving mainstreaming movement, visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective webpage.

The Utah Deaf Education

Core Group is Formed

Core Group is Formed

The Utah Deaf community was concerned that Steven W. Noyce, a long-time teacher and director of the Utah School for the Deaf, would seek to carry on Dr. Bitter's legacy, jeopardizing the ASL/English bilingual program they had worked so hard to establish when the Utah State Board of Education elected him superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind in August 2009. The state board disregarded the Utah Deaf community's outcry.

Steven Noyce was no stranger to the Utah Deaf community, having graduated from the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah between 1965 and 1972 (LinkedIn: Steven Noyce). We were concerned about his advocacy for oral education. In response, Ella Mae Lentz, a co-founder of the Deafhood Foundation and a vocal champion for deaf education, proposed founding the Deaf Education Core Group in April 2010. The group aimed to protect ASL/English bilingual education and fight inequality in the deaf education system.

Following the 2005 USD/JMS merger, the staff of Jean Massieu Charter School, along with Utah Deaf community leaders and administrators from the Utah Schools for the Deaf, worked together to ensure that the ASL/English bilingual educational approach, which was integral to JMS, received equal resources as the oral educational approach, which was USD's primary approach. Initially, JMS had a good working relationship with the Utah School for the Deaf. However, when the Utah State Board of Education appointed Steven W. Noyce, an avowed oralist and active member of the Alexander Graham Bell Association, as superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, the situation changed. There has been a long-standing debate in Utah, dating back to 1884, on whether to teach using oral or sign language methods in formal deaf education. After the merger, the debate subsided, and the ASL and oral (now called listening and spoken language) teams worked together peacefully. However, Superintendent Noyce used his position to push for LSL education, believing it superior to ASL/English, and vigorously promoted his mission at the Utah School for the Deaf. The revelation of Superintendent Noyce's hidden agenda sparked outrage among the Utah Deaf community. As a result, the controversy resurfaced and was more intense this time.

Julio Diaz, Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, Jeff Pollock, Dan Mathis, Stephanie Lowder Mathis, James (JR) Goff, Duane Kinner, and I were all part of the Utah Deaf Education Core Group. Bronwyn O'Hara, a hearing parent of Deaf children who battled Steven W. Noyce in the 1990s, joined the group to help us achieve our objectives. Although I've never met Dr. Bitter, I'm familiar with how his personality influenced his writing, which I found in his collection at the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah. It's clear that USDB Superintendent Noyce mirrored Dr. Bitter's personality, and their actions were strikingly similar. When I, the website's author, talk with the Deaf community about 'Deaf Education History in Utah,' I often refer to the 'Bitter Phase I group,' which was the first stage of their battle, and the 'Noyce Phase II group, 'which represented a similar battle in our approach and challenges. We were determined to improve deaf education in Utah despite facing significant challenges.

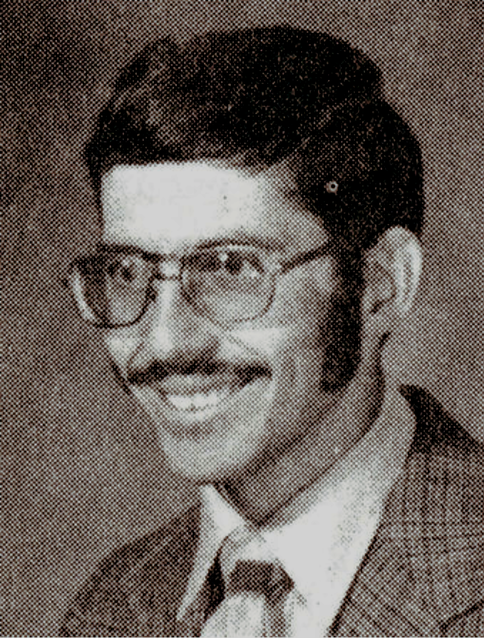

While serving on the USDB Institutional Council (2004–2010) and Legislative Task Force (2007–2009), I asked others who had come before me for help, such as Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, 87. On May 16, 2007, he responded to my email concerning the Utah Code, which governed the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. In the email, he told me, "It's up to young, vigorous, and enthusiastic deaf people like you to carry on." At the time, Robert and his wife, Mary, were enjoying their retirement, so I could not rely on his direct involvement when I requested assistance. During our conflict with USDB Superintendent Noyce in 2009, I recalled his words. Dr. Sanderson's statement encouraged me to continue the fight. The Utah Deaf Education Core Group was picking up where Dr. Sanderson, Ned C. Wheeler, W. David Mortensen, Lloyd H. Perkins, Kenneth L. Kinner, and others had left off in the fight for deaf education equality in Utah. The challenges that the young leaders were dealing with sprang from the past.

Julio Diaz, Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, Jeff Pollock, Dan Mathis, Stephanie Lowder Mathis, James (JR) Goff, Duane Kinner, and I were all part of the Utah Deaf Education Core Group. Bronwyn O'Hara, a hearing parent of Deaf children who battled Steven W. Noyce in the 1990s, joined the group to help us achieve our objectives. Although I've never met Dr. Bitter, I'm familiar with how his personality influenced his writing, which I found in his collection at the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah. It's clear that USDB Superintendent Noyce mirrored Dr. Bitter's personality, and their actions were strikingly similar. When I, the website's author, talk with the Deaf community about 'Deaf Education History in Utah,' I often refer to the 'Bitter Phase I group,' which was the first stage of their battle, and the 'Noyce Phase II group, 'which represented a similar battle in our approach and challenges. We were determined to improve deaf education in Utah despite facing significant challenges.