History of the

Jean Massieu School of the Deaf

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Published in 2021

Updated in 2024

Published in 2021

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

As a proud parent of two incredible Deaf children, Joshua and Danielle, I feel honored to have served on the Utah Deaf Education and Literacy, Inc. (UDEAL) board from 2003 to 2005. During that time, I had the opportunity to enroll my children at the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf (JMS), which UDEAL governed. It was a privilege to work alongside Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, the co-founder of JMS and a highly respected figure in the Deaf community. Together, we faced challenges in navigating the deaf educational system. These included a lack of resources for Deaf students, limited access to funding, and a general lack of understanding and acceptance of ASL/English bilingual education. We also had to overcome internal disputes with the UDEAL officials, which at times hindered our progress. The law that regulated the USDB presented another challenge, as it promoted mainstreaming and made it difficult for JMS to retain its students. Furthermore, the lack of permanent school facilities added complexity to the situation, all of which had an impact on JMS. However, our hard work and dedication paid off with the merger of JMS and the Utah School for the Deaf in 2005. This was a significant step in addressing these issues and ensuring that Deaf students had access to the resources and education they deserved. I vividly remember first hearing about JMS while attending Gallaudet Graduate School in Washington, DC, in 1999. At that time, I never imagined that I would have Deaf children or be involved with JMS. I appreciate being part of JMS and UDEAL and Minnie Mae's and others' sacrifices for the school's success. Without their efforts, my children might have had to choose between mainstreaming or moving out of state to attend a state school for the deaf. Thanks to JMS, my children could access an ASL/English bilingual environment on campus, which has been invaluable to their education and overall development. The following is a brief history of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf.

Thank you, Minnie Mae, for everything you did for JMS, as well as for Jeff Allen and Joe Zeidner, who contributed to the growth of the JMS community.

Jodi Becker Kinner

Thank you, Minnie Mae, for everything you did for JMS, as well as for Jeff Allen and Joe Zeidner, who contributed to the growth of the JMS community.

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Creation of the Utah Deaf

Bilingual and Bicultural Conference

Bilingual and Bicultural Conference

The Jean Massiue School of the Deaf was established as a result of the 1997 Utah Deaf Bilingual and Bicultural Conference. This significant event was made possible through the collaborative efforts of the Utah Deaf community, led by Shirley Hortie Platt, a dedicated Deaf Mentor in the Parent Infant Program (PIP) of the Utah School for the Deaf, serving families of Deaf children. Shirley played a key role in leading the conference and serving families with Deaf children. Their unity and determination were a response to the dissatisfaction with the quality of deaf education at the Utah School for the Deaf, as Deaf students' academic achievement was limited at both the Utah School for the Deaf and mainstream school placements. Their concerns were echoed by Gene Stewart, a Child of Deaf Adults and vocational rehabilitation counselor for the deaf, who addressed the Utah State Board of Education in 1977, describing the condition as being in the 'Dark Ages' (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, March 26, 1977).

As a solution, Shirley proposed the creation of the Utah Deaf Bilingual and Bicultural Conference, which was approved by the Utah Association for the Deaf. The term' bilingual and bicultural' refers to the recognition and promotion of both American Sign Language (ASL) and English, as well as Deaf culture, in the education of Deaf children. The conference, chaired by Shirley and hosted by the Utah Association for the Deaf, took place over two days on April 25–26, 1997, at the Eccles Conference Center in Ogden, Utah. Dr. Petra M. Horn-Marsh, the director of the Deaf Mentor program, supervised the conference (UAD Bulletin, June 1997; Shirley Hortie Platt, personal communication, November 7, 2008). This event marked a significant moment in the community's history.

Shirley, fueled by her unwavering determination to make a change, led the conference. She was deeply troubled by the high number of Utah Deaf children who were unable to use their natural language, the lack of progress in the Parent Infant Program, and the complete disregard for input from Deaf Mentors. Shirley remained resolute despite facing paternalistic and patronizing attitudes from USD teachers and administrators, most of whom were hearing. She was appalled by their ignorance and realized that if someone wanted to make a change, they had to do it themselves, so she did (Shirley Hortie Platt, personal communication, November 7, 2008).

The event was a testament to the success of the conference in bringing together a diverse range of presenters and attendees. Approximately four hundred people, many from out of state, graced the event with their presence. The conference was enriched by the insights of distinguished presenters. Dr. Lawrence "Larry" Fleischer, Department Chair of Deaf Studies at California State University-Northridge, discussed Deaf identity; Dr. Martina J. "MJ" Bienvenu, Director of the Language and Culture Center in Gaithersburg, Maryland, shed light on Deaf culture; Dr. Marlon "Lon" Kuntze from the University of California, Berkeley, delved into the topic of language; and Dr. Joseph "Jay" Innes from Gallaudet University shared his expertise on Deaf Education. Representatives from the Indiana School for the Deaf, including Diane Hazel Jones, David Geeslin, and Rebecca Pardee, shared their school's experience establishing a bilingual-bicultural program (UAD Bulletin, June 1997).

The conference was a big success, providing an unprecedented platform for people to shift their mindsets. It also aimed to foster a fresh perspective that appreciates the value of Deaf people. This paradigm change was more than just a goal; it was a hopeful vision of a more inclusive and understanding society. The conference also significantly contributed to this vision by influencing and changing the perceptions of Deaf individuals.

As a solution, Shirley proposed the creation of the Utah Deaf Bilingual and Bicultural Conference, which was approved by the Utah Association for the Deaf. The term' bilingual and bicultural' refers to the recognition and promotion of both American Sign Language (ASL) and English, as well as Deaf culture, in the education of Deaf children. The conference, chaired by Shirley and hosted by the Utah Association for the Deaf, took place over two days on April 25–26, 1997, at the Eccles Conference Center in Ogden, Utah. Dr. Petra M. Horn-Marsh, the director of the Deaf Mentor program, supervised the conference (UAD Bulletin, June 1997; Shirley Hortie Platt, personal communication, November 7, 2008). This event marked a significant moment in the community's history.

Shirley, fueled by her unwavering determination to make a change, led the conference. She was deeply troubled by the high number of Utah Deaf children who were unable to use their natural language, the lack of progress in the Parent Infant Program, and the complete disregard for input from Deaf Mentors. Shirley remained resolute despite facing paternalistic and patronizing attitudes from USD teachers and administrators, most of whom were hearing. She was appalled by their ignorance and realized that if someone wanted to make a change, they had to do it themselves, so she did (Shirley Hortie Platt, personal communication, November 7, 2008).

The event was a testament to the success of the conference in bringing together a diverse range of presenters and attendees. Approximately four hundred people, many from out of state, graced the event with their presence. The conference was enriched by the insights of distinguished presenters. Dr. Lawrence "Larry" Fleischer, Department Chair of Deaf Studies at California State University-Northridge, discussed Deaf identity; Dr. Martina J. "MJ" Bienvenu, Director of the Language and Culture Center in Gaithersburg, Maryland, shed light on Deaf culture; Dr. Marlon "Lon" Kuntze from the University of California, Berkeley, delved into the topic of language; and Dr. Joseph "Jay" Innes from Gallaudet University shared his expertise on Deaf Education. Representatives from the Indiana School for the Deaf, including Diane Hazel Jones, David Geeslin, and Rebecca Pardee, shared their school's experience establishing a bilingual-bicultural program (UAD Bulletin, June 1997).

The conference was a big success, providing an unprecedented platform for people to shift their mindsets. It also aimed to foster a fresh perspective that appreciates the value of Deaf people. This paradigm change was more than just a goal; it was a hopeful vision of a more inclusive and understanding society. The conference also significantly contributed to this vision by influencing and changing the perceptions of Deaf individuals.

The Creation of a Bilingual and Bicultural Committee

During the Utah Association for the Deaf conference on June 13–14, 1997, a significant event occurred when Dennis Platt, the husband of Shirlie Hortie Platt, who was the newly elected UAD president and a USDB Institutional Council member, established the Bilingual and Bicultural Committee. Also, David Samuelsen, a UAD member, proposed to appoint Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, a highly respected figure in the Deaf community, a professionally qualified, passionate advocate for ASL/English bilingual education, and a Deaf parent of three Deaf children, as the chair of the committee (David Samuelsen, personal communication, July 26, 2016). The Utah Association for the Deaf approved David's proposal, marking a significant shift in the landscape of deaf education. The committee focused on advocating for ASL/English bilingual education, and its work has had a positive impact on the community, providing hope for a better future in deaf education.

Minnie Mae was inspired by the 1997 Utah Deaf Bilingual and Bicultural Conference and was eager to contribute when elected chair of the Bi-Bi Committee. In her 1990 paper, "Exciting Developments in Deaf Education," she shared her enthusiasm and admiration for the Indiana School for the Deaf for adopting a bilingual-bicultural approach. It's no surprise that she would eventually become a JMS co-founder. Her passion was evident from the start, paving the way to co-founding the successful Jean Massieu School of the Deaf in 1999.

Throughout the campaign, the UAD committee strategically used the term 'Bi-Bi,' a shorthand for 'bilingual-bicultural, 'to underscore their vision of incorporating both ASL and English in the education of Deaf children. They also aimed to highlight the importance of integrating Deaf culture into the educational experience of Deaf children (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

One of the main goals of the Bi-Bi Committee was to explore the potential of introducing bilingual-bicultural education to the Utah School for the Deaf, which at that time only offered oral and total communication options (UAD Bulletin, July 1999; Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, April 23, 2011). The committee's first attempt to integrate the Bi-Bi program into the school was unsuccessful. The Bi-Bi Committee did not anticipate that their decision would lead to the creation of a deaf day school (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, April 23, 2011). Despite facing obstacles, their unwavering persistence and dedication led to the establishment of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf on August 29, 1999. This school later merged with the Utah School for the Deaf on June 3, 2005, to provide a bilingual and bicultural option called ASL/English bilingual. The Jean Massieu School of the Deaf continues to operate, providing Deaf students with access to both ASL and English on campus, empowering them to thrive and succeed. Thanks to Minnie Mae's dedication and steadfast leadership, JMS has been in operation since 1999. This achievement marked a significant milestone in Utah's deaf education, a historical turning point detailed in the following section below.

Minnie Mae was inspired by the 1997 Utah Deaf Bilingual and Bicultural Conference and was eager to contribute when elected chair of the Bi-Bi Committee. In her 1990 paper, "Exciting Developments in Deaf Education," she shared her enthusiasm and admiration for the Indiana School for the Deaf for adopting a bilingual-bicultural approach. It's no surprise that she would eventually become a JMS co-founder. Her passion was evident from the start, paving the way to co-founding the successful Jean Massieu School of the Deaf in 1999.

Throughout the campaign, the UAD committee strategically used the term 'Bi-Bi,' a shorthand for 'bilingual-bicultural, 'to underscore their vision of incorporating both ASL and English in the education of Deaf children. They also aimed to highlight the importance of integrating Deaf culture into the educational experience of Deaf children (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

One of the main goals of the Bi-Bi Committee was to explore the potential of introducing bilingual-bicultural education to the Utah School for the Deaf, which at that time only offered oral and total communication options (UAD Bulletin, July 1999; Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, April 23, 2011). The committee's first attempt to integrate the Bi-Bi program into the school was unsuccessful. The Bi-Bi Committee did not anticipate that their decision would lead to the creation of a deaf day school (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, April 23, 2011). Despite facing obstacles, their unwavering persistence and dedication led to the establishment of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf on August 29, 1999. This school later merged with the Utah School for the Deaf on June 3, 2005, to provide a bilingual and bicultural option called ASL/English bilingual. The Jean Massieu School of the Deaf continues to operate, providing Deaf students with access to both ASL and English on campus, empowering them to thrive and succeed. Thanks to Minnie Mae's dedication and steadfast leadership, JMS has been in operation since 1999. This achievement marked a significant milestone in Utah's deaf education, a historical turning point detailed in the following section below.

The Bi-Bi Committee Meets

USDB Superintendent Lee Robinson

USDB Superintendent Lee Robinson

On March 30, 1998, Minnie Mae and Jeff Allen, a father of a Deaf daughter, who were both committee leaders, met with Superintendent Dr. Lee Robinson and Assistant Superintendent Joseph DiLorenzo of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. The main objective of the meeting was to discuss the possibility of adding a Bi-Bi educational option to the Utah School for the Deaf. The committee strongly believed this would be a beneficial addition considering the Federal Bilingual Education Act of 1988, which included Deaf students protected by the legal definition of native language and limited English proficiency. Furthermore, in 1994, the Utah State Legislature passed Utah Senate Bill 42, which legally recognized American Sign Language as a language, making it an ideal time for the Bi-Bi Committee to make their request. However, school administrators declined the proposal, stating they were still not interested in incorporating ASL into their curriculum (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, 2010). Despite the setback, the Utah Deaf community, parents of Deaf children, and Deaf friends provided the Bi-Bi committee with unwavering support (UAD Bulletin, May 1988).

The Utah Charter Schools Act

The Bi-Bi Committee held regular meetings every two weeks; over time, more hearing parents began attending. Their increasing involvement is evidence of the growing awareness of the importance of providing their Deaf children with the best possible education. The Deaf community in Utah backed this cause, acknowledging that Deaf children were the future leaders of the Utah Association of the Deaf. The committee's main goal was to establish or find a program or school that could teach Deaf students using the "Bi-Bi" approach (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, June 1998; Wilding-Diaz, UAD Bulletin, June 1999).

During the committee's work, the Utah State Legislature was working on a charter school bill that caught the attention of the Bi-Bi Committee. The committee resolved to concentrate its efforts on enacting the bill that would permit the establishment of charter schools within the state. The Utah Legislature successfully passed the Utah Charter Schools Act at the end of the 1998 legislative session. This act provided the legal framework for the establishment of charter schools, including the one proposed by the Bi-Bi Committee (Utah Charter Schools Act, 1998; Wilding-Diaz, UAD Bulletin, June 1999).

In May 1998, the Bi-Bi Committee took a significant step by contacting Governor Mike Leavitt's Office and the Utah State Office of Education to apply for a charter school for the deaf. The timing of this action was perfect, as the Committee began working on a charter school proposal in June 1998, which the Utah State Board of Education later approved. The mission of this new charter school was to promote American Sign Language (ASL) as the language of communication and instruction. The Bi-Bi Committee submitted their application for the Utah Charter Schools for the academic year 1998-1999 on July 17, 1998 (Utah Charter Schools Application 1998-1999, July 17, 1998).

On July 29, 1998, a significant milestone was achieved for Deaf children when the Utah State Board of Education approved the proposal for the Bi-Bi educational option. This official recognition is a reassuring step forward for deaf education. The Tuacahan High School for the Performing Arts was the first to receive approval, and the Bi-Bi Committee's proposal was the second. By November of the same year, the Utah Board of Education planned to approve applications from six more schools (UAD Bulletin, September 1998). This milestone was achieved through the collaborative efforts of co-founders Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz and Jeff Allen. Their shared vision and dedication to deaf education led to the establishment of the Jean Massieu School for the Deaf, which began operating as a public charter school in 1999.

During the committee's work, the Utah State Legislature was working on a charter school bill that caught the attention of the Bi-Bi Committee. The committee resolved to concentrate its efforts on enacting the bill that would permit the establishment of charter schools within the state. The Utah Legislature successfully passed the Utah Charter Schools Act at the end of the 1998 legislative session. This act provided the legal framework for the establishment of charter schools, including the one proposed by the Bi-Bi Committee (Utah Charter Schools Act, 1998; Wilding-Diaz, UAD Bulletin, June 1999).

In May 1998, the Bi-Bi Committee took a significant step by contacting Governor Mike Leavitt's Office and the Utah State Office of Education to apply for a charter school for the deaf. The timing of this action was perfect, as the Committee began working on a charter school proposal in June 1998, which the Utah State Board of Education later approved. The mission of this new charter school was to promote American Sign Language (ASL) as the language of communication and instruction. The Bi-Bi Committee submitted their application for the Utah Charter Schools for the academic year 1998-1999 on July 17, 1998 (Utah Charter Schools Application 1998-1999, July 17, 1998).

On July 29, 1998, a significant milestone was achieved for Deaf children when the Utah State Board of Education approved the proposal for the Bi-Bi educational option. This official recognition is a reassuring step forward for deaf education. The Tuacahan High School for the Performing Arts was the first to receive approval, and the Bi-Bi Committee's proposal was the second. By November of the same year, the Utah Board of Education planned to approve applications from six more schools (UAD Bulletin, September 1998). This milestone was achieved through the collaborative efforts of co-founders Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz and Jeff Allen. Their shared vision and dedication to deaf education led to the establishment of the Jean Massieu School for the Deaf, which began operating as a public charter school in 1999.

The Bi-Bi Committee established a new school in September 1998, with the goal of opening it in the fall of 1999 (UAD Bulletin of September 1998). The committee proposed three names for the school, all of which were significant figures in the Deaf community: Alice Cogswell School, George Veditz School, and Jean Massieu School. These names held historical significance within the Deaf community. The committee held a vote and chose Jean Massieu, a deeply respected figure in the Deaf community, as the school's name (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

The Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, also known as JMS, was named after Jean Massieu, a remarkable French Deaf teacher. His influence reached far beyond France, with visits from princes, philosophers, and even the pope seeking his wisdom. Laurent Clerc, a Deaf man who, along with Thomas H. Gallaudet, established the first Deaf school in the United States, the American School for the Deaf, in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817, greatly benefited from Jean Massieu's teaching and mentoring. Loida R. Canlas of the Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center credits Jean Massieu's linguistic skills for his creation of an English-French dictionary in 1808. His successful students, many of whom directed schools for Deaf children in other countries, are a testament to his global impact (UAD Bulletin, June 1998).

The Utah Charter Schools Act required all charter schools to be non-profit organizations. In 1998, the committee established Utah Deaf Education and Literacy, Inc. (UDEAL) as a separate non-profit entity from the Utah Association for the Deaf. UDEAL's main goal was establishing, managing, and supervising a new charter school, with a secondary objective of raising funds (UAD Bulletin, September 1998; Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

The Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, also known as JMS, was named after Jean Massieu, a remarkable French Deaf teacher. His influence reached far beyond France, with visits from princes, philosophers, and even the pope seeking his wisdom. Laurent Clerc, a Deaf man who, along with Thomas H. Gallaudet, established the first Deaf school in the United States, the American School for the Deaf, in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817, greatly benefited from Jean Massieu's teaching and mentoring. Loida R. Canlas of the Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center credits Jean Massieu's linguistic skills for his creation of an English-French dictionary in 1808. His successful students, many of whom directed schools for Deaf children in other countries, are a testament to his global impact (UAD Bulletin, June 1998).

The Utah Charter Schools Act required all charter schools to be non-profit organizations. In 1998, the committee established Utah Deaf Education and Literacy, Inc. (UDEAL) as a separate non-profit entity from the Utah Association for the Deaf. UDEAL's main goal was establishing, managing, and supervising a new charter school, with a secondary objective of raising funds (UAD Bulletin, September 1998; Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

Jean Massieu School of the Deaf

Opens Its Doors

Opens Its Doors

After receiving approval, the Bi-Bi Committee, a group of dedicated individuals with expertise in Deaf education, began working to make the charter school a reality. This involved finding a suitable location, securing more funding, choosing a curriculum, hiring teachers, and purchasing supplies, among other things (UAD Bulletin, September 1998). At the same time, the UDEAL Board took on responsibilities such as fundraising, program development, preparing for Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meetings, resolving transportation issues, managing building and site concerns, and addressing technology-related matters.

On August 29, 1999, the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf opened its doors to 21 students from preschool through third grade. Over the years, JMS has expanded its program by one grade each year, and it now offers education from pre-kindergarten through 12th grade. JMS also provides complete language accessibility in both American Sign Language and English (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

Despite operating as an independent Bi-Bi charter school for six years, JMS has shown remarkable resilience, relying on donations and state funding based on student enrollment. The state funds were not enough, leading JMS to face financial difficulties, but the school has continued to provide quality education. However, the Utah School for the Deaf hesitated to introduce the ASL/English bilingual program, formerly the bilingual-bicultural option, to parents and students. The Parent Infant Program of the Utah School for the Deaf and its staff did not recognize JMS as a viable option for families seeking educational opportunities in Utah. They mistakenly labeled it as a school for students with low academic abilities or those needing to catch up.

On August 29, 1999, the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf opened its doors to 21 students from preschool through third grade. Over the years, JMS has expanded its program by one grade each year, and it now offers education from pre-kindergarten through 12th grade. JMS also provides complete language accessibility in both American Sign Language and English (Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

Despite operating as an independent Bi-Bi charter school for six years, JMS has shown remarkable resilience, relying on donations and state funding based on student enrollment. The state funds were not enough, leading JMS to face financial difficulties, but the school has continued to provide quality education. However, the Utah School for the Deaf hesitated to introduce the ASL/English bilingual program, formerly the bilingual-bicultural option, to parents and students. The Parent Infant Program of the Utah School for the Deaf and its staff did not recognize JMS as a viable option for families seeking educational opportunities in Utah. They mistakenly labeled it as a school for students with low academic abilities or those needing to catch up.

The Merger Agreement Between

the Utah School for the Deaf

and Jean Massieu School of the Deaf

the Utah School for the Deaf

and Jean Massieu School of the Deaf

The UDEAL board had to reevaluate its direction due to financial pressures. On the other hand, incorporating the ASL/English bilingual option into the state school would make the Utah School for the Deaf more open to its support. Therefore, the merger was not only a strategic move but a necessity to make JMS and its philosophy more accessible to Deaf children and their families across the state. This urgency highlights the importance of the proposal. Furthermore, according to Laurel Stimpson's UAD Bulletin in March 2005, the merger aimed to secure JMS's quality accessibility services, ensure financial stability, and enhance employee salaries and benefits.

In 2004, the Jean Massieu Charter School, facing significant financial difficulties, sought to merge with the Utah Schools for the Deaf to offer parents ASL/English bilingual education options. However, the Utah School for the Deaf initially hesitated to include the ASL/English bilingual program. As a result, the UDEAL Board sought the help of legislators to make the merger possible. One of the UDEAL board members, Joe Zeidner, an attorney with a Deaf child, lobbied the state legislature to have the Utah School for the Deaf legally incorporate the JMS program. USDB Superintendent Linda Rutledge had no choice but to support the merger, or else the USDB's funding would be cut. In the end, the USD merged the JMS program to guarantee bilingual education for Deaf children.

In 2004, the Jean Massieu Charter School, facing significant financial difficulties, sought to merge with the Utah Schools for the Deaf to offer parents ASL/English bilingual education options. However, the Utah School for the Deaf initially hesitated to include the ASL/English bilingual program. As a result, the UDEAL Board sought the help of legislators to make the merger possible. One of the UDEAL board members, Joe Zeidner, an attorney with a Deaf child, lobbied the state legislature to have the Utah School for the Deaf legally incorporate the JMS program. USDB Superintendent Linda Rutledge had no choice but to support the merger, or else the USDB's funding would be cut. In the end, the USD merged the JMS program to guarantee bilingual education for Deaf children.

Joe Zeidner's hard work for Utah Deaf Education and Literacy, Inc. was instrumental in the Utah State Legislature passing 'intent language' during the 2004 session, ultimately leading to JMS's merger with USDB. The UDEAL board formed a steering committee that developed letters of intent and terms of agreement for the merger, and negotiations between the USDB and JMS took nearly a year. After a meticulous and thorough review and approval by Utah Deaf Education and Literacy, the USDB Institutional Council, and the Utah State Board of Education, the Utah State Board of Education officially approved the USD/JMS merger in 2005, instilling confidence in the decision-making process.

On June 3, 2005, at JMS, Kim Burningham, the Chair of the Utah State Board of Education, Linda Rutledge, the USDB Superintendent, and Craig Radford, the UDEAL Chair, signed documents following their approval by the Utah State Board of Education, represented by Dr. Patti Harrington, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction (Stimpson, UAD Bulletin, July 2005). The UDEAL board members who witnessed the merger signatures were Chris Palaia (Deaf), Laurel Stimpson (Deaf), Sean Williford, Joe Ziedner, LaDawn Rinlinsbaker, Jeff Allen, Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz (Deaf), and me (Deaf). This merger brought about a significant change, offering parents and students a new ASL/English bilingual option at the Utah School for the Deaf. Thanks to Joe Zeidner's legislative efforts, the Utah Legislature and the Utah State Board of Education, through their remarkable collaboration, authorized the merger of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf with the Utah School for the Deaf. His drive and lobbying efforts for deaf education will be remembered for years to come.

The Growing Pains of the Merger

The Utah School for the Deaf, in a collaborative effort with JMS, overcame challenges and implemented changes. This 'growing pains' period was a demonstration of our commitment to ASL/English bilingual education. Michelle Tanner, the Associate Superintendent, played a pivotal role in establishing the hybrid program in August 2016, a significant milestone that marked our progress and success. This program facilitated 'unbiased collaboration' between the listening and spoken language program and the ASL/English bilingual program, making personalized deaf education placement a reality. For more detailed information, we invite you to visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream webpage.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of JMS and its role in working with the Utah School for the Deaf, we encourage you to delve into the 'Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, JMS Co-Founder of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf' webpage. This webpage offers a rich overview of JMS, its founders, and their vision for deaf education, including ASL/English bilingual education. Exploring this webpage will deepen your understanding and ignite your curiosity about JMS's rich history and vision.

Today, the Utah School for the Deaf offers four ASL/English bilingual schools: Kenneth C. Burdett School for the Deaf in Ogden, Jean Massieu School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Elizabeth DeLong School for the Deaf in Springville, and Southern Utah School for the Deaf in St. George. These schools are named after three prominent Deaf individuals: Kenneth C. Burdett, Jean Massieu, and Elizabeth DeLong.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of JMS and its role in working with the Utah School for the Deaf, we encourage you to delve into the 'Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, JMS Co-Founder of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf' webpage. This webpage offers a rich overview of JMS, its founders, and their vision for deaf education, including ASL/English bilingual education. Exploring this webpage will deepen your understanding and ignite your curiosity about JMS's rich history and vision.

Today, the Utah School for the Deaf offers four ASL/English bilingual schools: Kenneth C. Burdett School for the Deaf in Ogden, Jean Massieu School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Elizabeth DeLong School for the Deaf in Springville, and Southern Utah School for the Deaf in St. George. These schools are named after three prominent Deaf individuals: Kenneth C. Burdett, Jean Massieu, and Elizabeth DeLong.

JMS Yellowjackets Mascot

In 2003, Doug Stringham, a senior designer and art director at Stephen Hales Creative, Inc. in Provo, Utah, designed the yellow jacket mascot. Despite being a hearing man, Doug is deeply involved in the Deaf community and volunteered his time and skills to create the design. The yellow jacket, with its "J" shape and hands formed in the "M" and "S" hand shapes, symbolizes JMS and its connection to the Utah Deaf community (Leanna Turnman, personal communication, 2009; Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, personal communication, March 29, 2010).

The Jean Massieu School of the Deaf

Operated at Various Locations

Operated at Various Locations

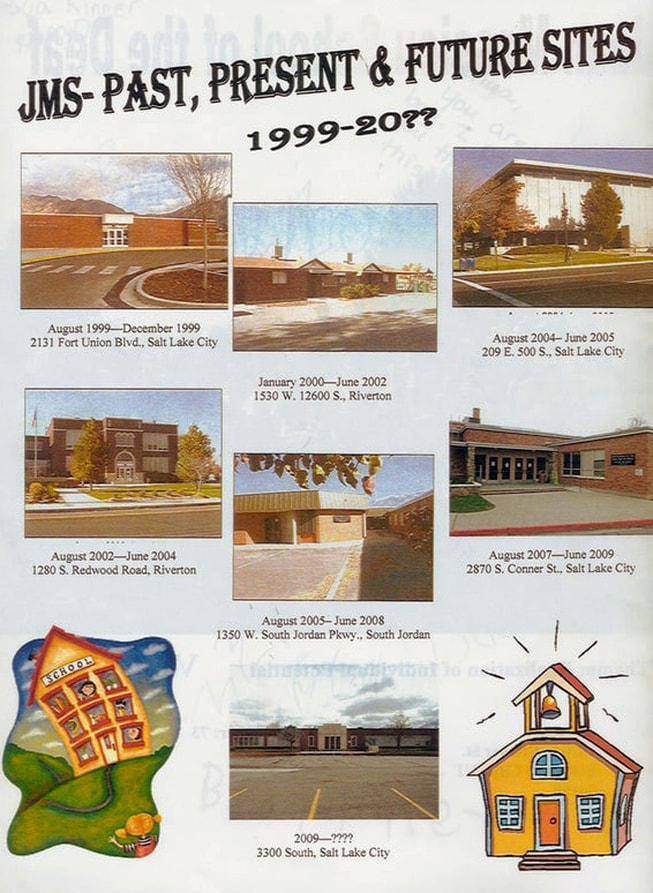

- Bella Vista Elementary School 2131 East 7000 South, Salt Lake City – August – November 1999

- Riverton at 1530 West 12600 South, Unit 3 and 4 – November 1999 – 2002

- Riverton City Library 12750 South Redwood Road, Riverton – 2002 – 2004

- Salt Lake Arts Academy 209 E. 500 South, Salt Lake City – 2004 – 2005

- USDB/JMS 1350 West 10400 South, South Jordan – 2005 – 2008

- USDB Extension Conner Street 2870 Connor Street Salt Lake City, UT 84109 – 2008 – 2010

- Libby Edwards Elementary 1655 E. 3300 South Salt Lake City, Utah 84106 - 2010- present