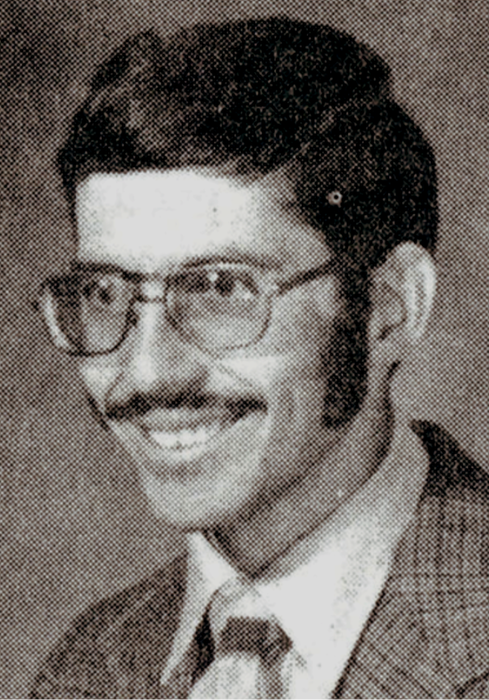

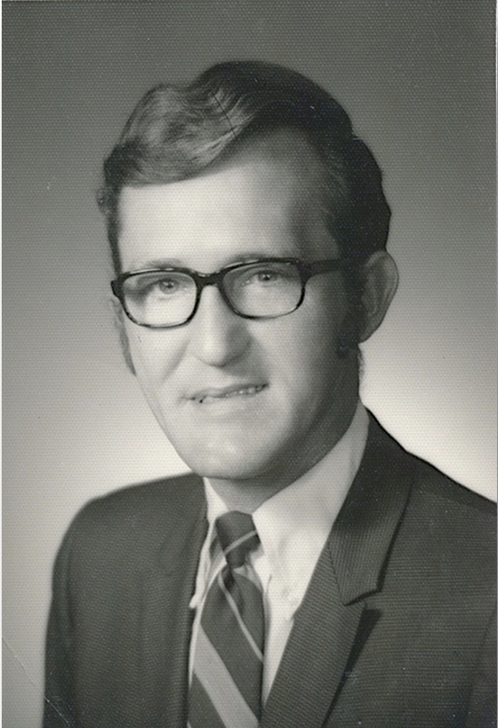

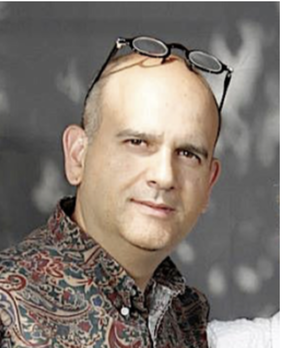

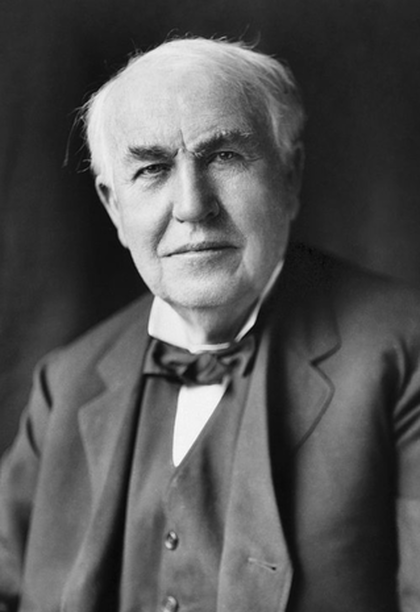

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson:

"Mainstreaming Is Not the Answer

for All Deaf Children"

"Mainstreaming Is Not the Answer

for All Deaf Children"

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

As a parent of two Deaf children, my passion for deaf education comes from my personal journey. My father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, also sparked my interest and shared with me the history of deaf education in Utah, including its oral and mainstreaming impact. This inspired me to meticulously document the controversial events of that era. If it weren't for him, I wouldn't be able to advocate for my kids without knowing the history. My studies at the Gallaudet School Social Work Program further deepened my understanding of the complexities of education, legislation, and policy. Moreover, my role on the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind has truly empowered me to advocate for my children and others in Utah who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled. This platform has given me the strength and voice to make a difference.

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

While advocating for deaf education in Utah, I have gained firsthand experience with the Utah Code that regulates the Utah School for the Deaf. The code has been promoting mainstreaming for Deaf and hard of hearing students, and the Utah School for the Deaf has been a pioneer in mainstreaming since 1959. During my research for the history website, I discovered an article in the 1992 UAD Bulletin by our Deaf Education Advocate, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, titled "Mainstreaming is Not the Answer for All Deaf Children." Despite the article's publication, the mainstreaming trend continued until the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf merged with the Utah School for the Deaf in 2005, which drastically changed its dynamic. The Utah Code had a significant impact on JMS, leading to a decline in student enrollment in mainstream settings. However, things changed for the better when we successfully advocated for a change in the law in 2009, as explained on this webpage.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

While advocating for deaf education in Utah, I have gained firsthand experience with the Utah Code that regulates the Utah School for the Deaf. The code has been promoting mainstreaming for Deaf and hard of hearing students, and the Utah School for the Deaf has been a pioneer in mainstreaming since 1959. During my research for the history website, I discovered an article in the 1992 UAD Bulletin by our Deaf Education Advocate, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, titled "Mainstreaming is Not the Answer for All Deaf Children." Despite the article's publication, the mainstreaming trend continued until the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf merged with the Utah School for the Deaf in 2005, which drastically changed its dynamic. The Utah Code had a significant impact on JMS, leading to a decline in student enrollment in mainstream settings. However, things changed for the better when we successfully advocated for a change in the law in 2009, as explained on this webpage.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

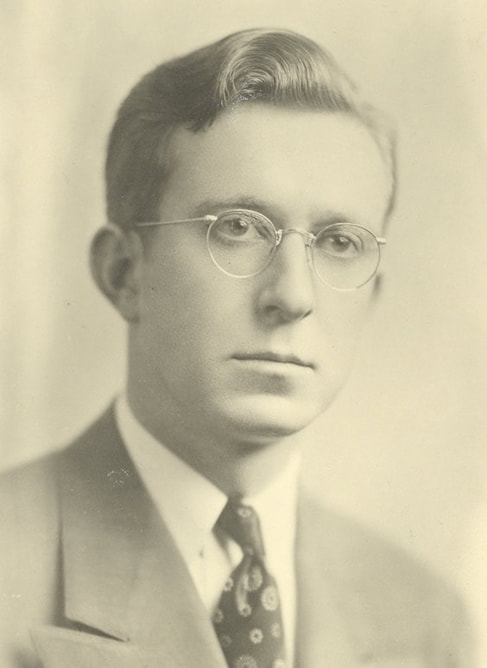

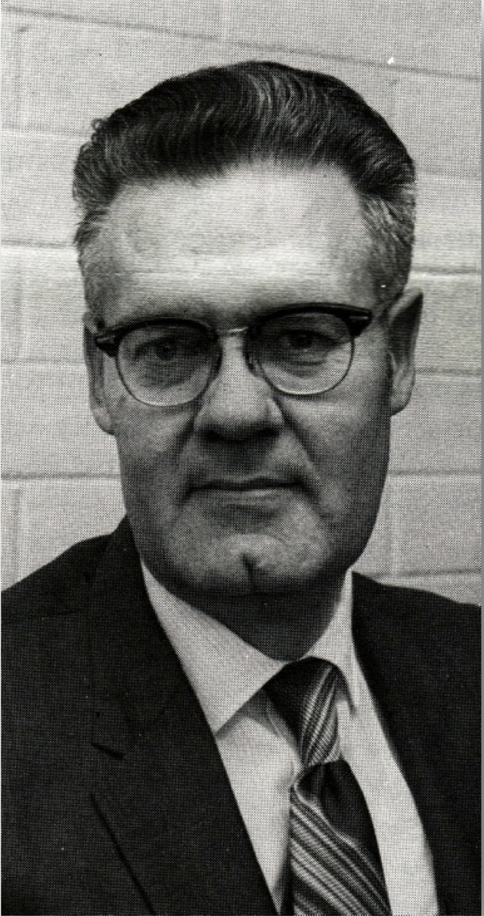

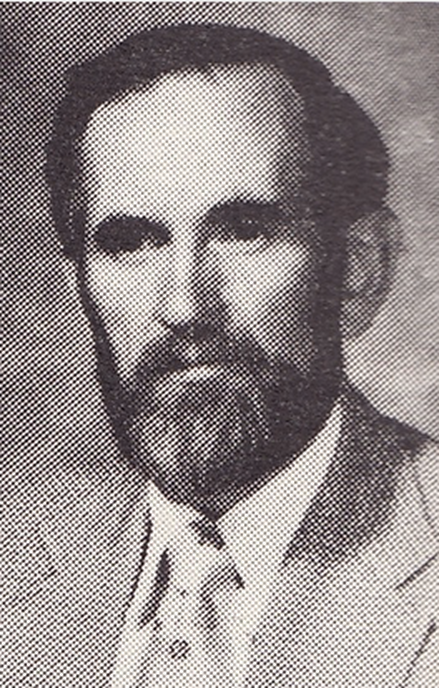

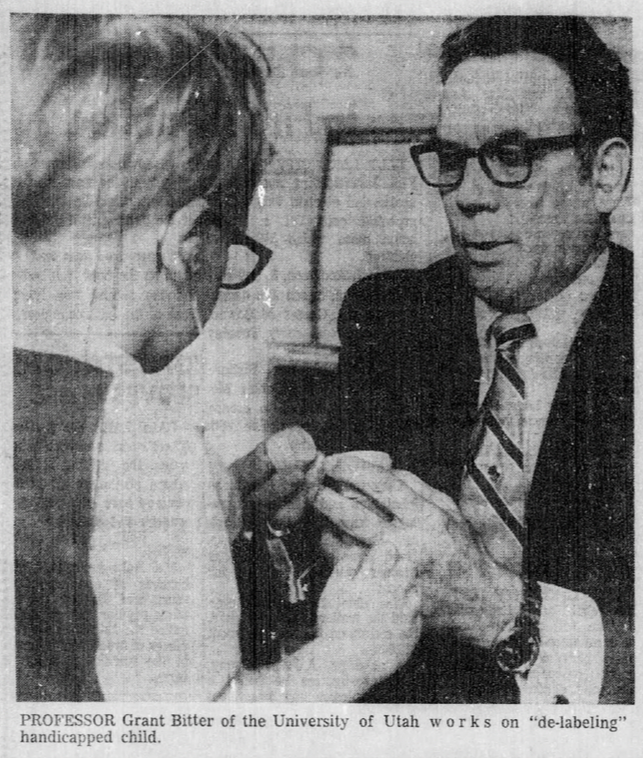

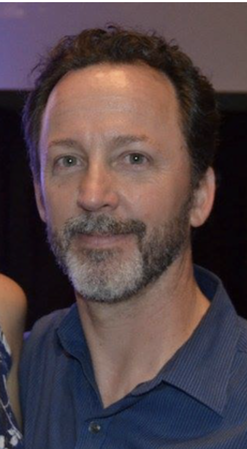

Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

the Father of Mainstreaming

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

During Martha's tenure on the Board of Trustees in 1896, a significant effort was made to address the lack of a law requiring Deaf and Blind children to attend the state institution. Martha and her board members urgently wrote a letter to the Utah governor and legislature, requesting that these children be educated at the state institute rather than in public schools. Their letter specifically recommended a legislative requirement for these children's attendance at the state institution, emphasizing the life-changing impact of specialized education. The report of the Utah State School for the Deaf and Dumb and the State School for the Blind, 1896, as detailed in the section below, provides a clearer picture of the content of this letter and its impact (Report of the Utah State School for the Deaf and Dumb and the State School for the Blind, 1896). After being elected as a senator, Martha continued her advocacy, spearheading a proposal for a mandatory school bill, which was successfully passed in 1896, bringing about positive change for Deaf and Blind children.

However, in the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990). It is likely that Dr. Bitter disagreed with Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon and her team's proposal to mandate the education of Deaf children at the state institution.

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter has also formally demanded the termination of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, two esteemed advocates for sign language, due to what he perceives as their interference with his mission to promote oral and mainstream education. He has also expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, as he felt it did not align with his educational goals. Finally, he has asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected chairperson of the committee, to resign due to her decision to invite representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he perceived as a drift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf showed remarkable resilience when faced with challenges from Dr. Bitter, marking a significant turning point in their history.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. His journey began at the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked as a teacher and curriculum coordinator. His passion for education led him to become a director and professor in the Teacher Training Program, where he focused primarily on oral education under the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. Dr. Bitter also served as the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

On top of that, Dr. Bitter and other parents firmly supported oral education and refused to send their Deaf children to Ogden's deaf residential campus. As a result, in 1959, the Utah School for the Deaf established an Extension Division in Salt Lake City, Utah, allowing Deaf students to attend classes close to their homes, paving the way for the mainstreaming movement. Dr. Bitter taught Deaf students at the USD Extension-Salt Lake City program between 1960 and 1962 (Utahn, 1963). He later became the Extension Division curriculum coordinator, advocating for the inclusion of all Deaf and hard of hearing students in public schools (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1969). With Dr. Bitter's push, the Utah School for the Deaf quickly created Extension Divisions around Utah to provide a day program for Deaf students in heavily populated areas.

The demographics of Deaf students at the Utah School for the Deaf began to change in 1961 as the proportion of Deaf individuals with additional disabilities increased. Hearing aids were starting to improve, giving Deaf individuals with better hearing aids the opportunity to interact with hearing people. The number of people who became deaf later in life began to decline, while the number of those born deaf began to rise. Before losing their hearing, half of the Deaf students at the Utah School for the Deaf had acquired a good language foundation. However, the growing population of Deaf individuals was impeding their language development. Before the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was established in 1965, the Utah Deaf community heavily relied on hard of hearing individuals who learned their language before using hearing aids, and those who lost their hearing afterward had acquired good speaking ability. The Utah Association of the Deaf predicted that in the future, there would be fewer such individuals and more Deaf people with additional disabilities, further complicating the picture (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1961, p. 2).

As more Deaf children without disabilities integrated into mainstream education, the number of Deaf students with disabilities at Ogden's residential campus increased in the 1960s and 1970s. The Utah Association of the Deaf's prediction about this trend proved to be accurate. The Utah School for the Deaf established self-contained deaf classes in local public schools to facilitate mainstreaming. Deaf students who excelled academically or were at the same level as their peers had the option to enroll in full inclusion programs within their school districts. However, the Utah Association of the Deaf and the Utah Deaf community remained dissatisfied with the quality of education at the Utah School for the Deaf, as discussed in Institutional Council meetings (Bronwyn O’Hara, personal communication, August 27, 2009).

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

On top of that, Dr. Bitter and other parents firmly supported oral education and refused to send their Deaf children to Ogden's deaf residential campus. As a result, in 1959, the Utah School for the Deaf established an Extension Division in Salt Lake City, Utah, allowing Deaf students to attend classes close to their homes, paving the way for the mainstreaming movement. Dr. Bitter taught Deaf students at the USD Extension-Salt Lake City program between 1960 and 1962 (Utahn, 1963). He later became the Extension Division curriculum coordinator, advocating for the inclusion of all Deaf and hard of hearing students in public schools (The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1969). With Dr. Bitter's push, the Utah School for the Deaf quickly created Extension Divisions around Utah to provide a day program for Deaf students in heavily populated areas.

The demographics of Deaf students at the Utah School for the Deaf began to change in 1961 as the proportion of Deaf individuals with additional disabilities increased. Hearing aids were starting to improve, giving Deaf individuals with better hearing aids the opportunity to interact with hearing people. The number of people who became deaf later in life began to decline, while the number of those born deaf began to rise. Before losing their hearing, half of the Deaf students at the Utah School for the Deaf had acquired a good language foundation. However, the growing population of Deaf individuals was impeding their language development. Before the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was established in 1965, the Utah Deaf community heavily relied on hard of hearing individuals who learned their language before using hearing aids, and those who lost their hearing afterward had acquired good speaking ability. The Utah Association of the Deaf predicted that in the future, there would be fewer such individuals and more Deaf people with additional disabilities, further complicating the picture (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1961, p. 2).

As more Deaf children without disabilities integrated into mainstream education, the number of Deaf students with disabilities at Ogden's residential campus increased in the 1960s and 1970s. The Utah Association of the Deaf's prediction about this trend proved to be accurate. The Utah School for the Deaf established self-contained deaf classes in local public schools to facilitate mainstreaming. Deaf students who excelled academically or were at the same level as their peers had the option to enroll in full inclusion programs within their school districts. However, the Utah Association of the Deaf and the Utah Deaf community remained dissatisfied with the quality of education at the Utah School for the Deaf, as discussed in Institutional Council meetings (Bronwyn O’Hara, personal communication, August 27, 2009).

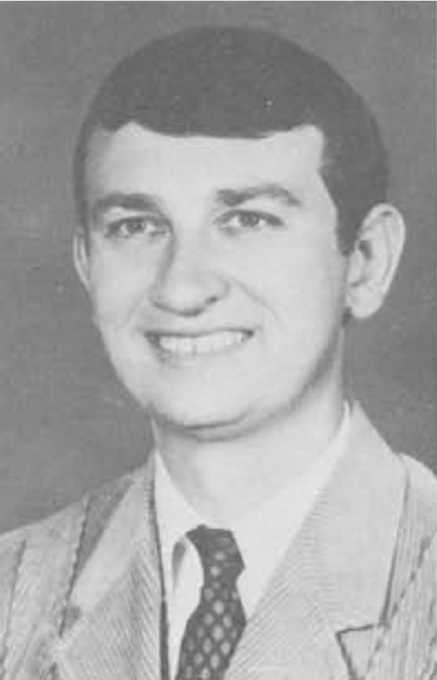

Robert G. Sanderson Defends the

Utah School for the Deaf

Utah School for the Deaf

The proposal to mainstream all Deaf children was initially discussed in the April 20, 1959, edition of a Salt Lake City newspaper. An article titled "It's Leave Home or Education Ends" by William Smiley advocated for the establishment of a day school in Salt Lake City for Deaf children using an oral approach (Smiley, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 20, 1959).

In response to William Smiley's article, Robert G. Sanderson, known as "Sadie" and "Bob," a 1936 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf who officially became a Deaf education advocate in 1955, presented a compelling argument on April 30, 1959, titled "Ogden School Best for Deaf Children." In an article, Bob defended the Utah School for the Deaf's use of sign language for communication. He emphasized the crucial role of sign language in the lives of Deaf children. Bob recognized the rights of parents to request special classes for their Deaf children in Salt Lake City, Utah. However, he opposed the notion that oral advocates deceive parents by emphasizing lip-reading and speech over education. Bob argued that a Deaf child attending the residential school in Ogden, Utah, received a better education compared to attending an oral day school. He also compared the education provided at the Utah School for the Deaf to that of a regular public school for hearing children. Bob highlighted the excellent academic instruction and vocational training available at the Utah School for the Deaf, urging parents to prioritize their child's education over their emotions when choosing a school. He also stressed that speech and lip-reading abilities would develop over time based on the child's capabilities, a crucial point often overlooked in the debate. In his conclusion, Bob emphasized that sign language is the natural and primary means of communication for Deaf children, and it was unreasonable for parents to deny their Deaf children the use of it. Bob stated that learning the sign language would enable parents and children to communicate and bridge the language barrier sooner. He emphasized again that speech and lip-reading skills would develop over time based on each child's abilities (Sanderson, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 30, 1959).

The Utah School for the Deaf graduates and Utah Association of the Deaf officials, G. Leon Curtis and Ray G. Wenger, also a member of the Advisory Council for the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, wrote in support of Robert Sanderson. Their newspaper pieces were in response to William Smiley's article (above) and Elizabeth H. Spear's "The Case for Oral Education of the Deaf," in which she disagreed with Robert. Leon and Ray highlighted in their writings that both speech lessons and sign language classes were available at the Utah School for the Deaf. They recommended that anyone interested attend the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah (Curtis, The Salt Lake Tribune, May 5, 1959; Wenger, The Salt Lake Tribune, May 12, 1959). They also said Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder could arrange a campus tour. They also assured the students' cheerful expressions would prove that the USD was excellently developing happy, self-sufficient Deaf adults (Sanderson, The Salt Lake Tribune, May 2, 1959).

The First Concept of Mainstreaming

at the Stewart Training Program

at the Stewart Training Program

The first concept of mainstreaming Deaf and hard of hearing students began with parents of Deaf children in the Salt Lake area of Utah. They did not want to send their children to the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah. Instead, they worked with the Stewart Training School, a teacher training school at the University of Utah, to establish a local oral day school. In the fall of 1956, the Stewart Training School opened to provide an oral classroom for Deaf students (Jonathon Hodson, personal communication, January 31, 2022). Since then, the mainstreaming idea has gained popularity in Utah, with the Utah School for the Deaf expanding outreach programs in school districts.

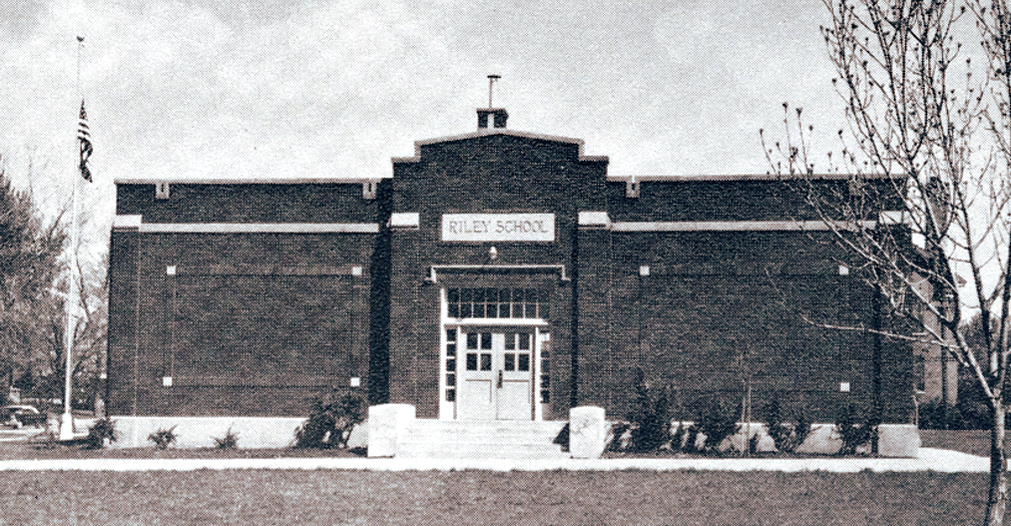

Paul Williams Hodson, who enrolled his five-year-old son Jonathan in the Stewart Training program, was one of these parents. This was not just a cause, but a deeply personal journey for them. Jonathan's teacher, Miss Hunt, was a pivotal figure in his life, and she later taught at Riley Elementary School in 1959 (Jonathon Hodson, personal communication, January 31, 2022). The Stewart Training School, where Jonathan received his education, was, as the oral community called it, a beacon of hope for parents of Deaf children, providing them with oral education using speech and listening skills instead of sign language (The Utah Eagle, October and November 1960).

The Utah School for the Deaf has established an Extension Division for Deaf Students in their Neighborhood Homes

However, the Stewart Training School became overcrowded in the late 1950s, especially among kindergarten-age students. They could no longer serve the Deaf and hard of hearing students (Jonathon Hodson, personal communication, May 29, 2011). Due to the overcrowding of the Stewart Training School, the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, faced opposition from parents who feared institutionalization, isolation, and segregation, as Dr. Bitter called it in his interview with the University of Utah in 1987 (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). To address this concern, the Utah School for the Deaf sought assistance from Dr. Allen Bateman, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, to partner with the Salt Lake City School District to support the parents. This collaboration led to the development of the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf, marking the beginning of mainstreaming for Deaf and hard of hearing students. Dr. Allen E. Bateman responded positively and supported the initiative (The Utah Eagle, October and November 1960; The Utah Eagle, January 1968).

In 1959, with the collaboration of the Utah State Board of Education, the legislature, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Salt Lake City Schools District, Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder of the Utah School for the Deaf and the Blind established the first extension classroom for oral students in public schools. This allowed these students to continue their education at home (The Utah Eagle, January 1968; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). The Extension Division, which began in 1959, first offered oral classes to elementary school students (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Utah School for the Deaf 100th Year Anniversary Alumni Reunion, 1984). At that time, students had the option to attend a local public school or the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, where they could get the necessary academic and vocational skills for graduation (The Utah Eagle, October and November 1960).

The teachers in the extension classrooms followed the curriculum of the Utah School for the Deaf in the elementary school. In the upper grades, the curriculum was gradually adapted to parallel the curriculum of the Salt Lake City School District (The Utah Eagle, January 1968). Students were integrated into regular public schools as part of their education transition. With careful planning, the students gradually transition from intensive speech, speech-reading, and listening skills to public school classes. At first, they began integrating with hearing students during recess and lunch, then moved on to non-academic subjects like physical education, art, industrial arts, and homemaking. The Extension Division also assigned prepared students to more advanced academic classes for one or more periods during the day. The Utah School for the Deaf eventually added the Total Communication Program to its Extension Division, following a similar process to that of oral students. The Utah School for the Deaf funded the programs and rented space from the local public school district (The Utah Eagle, January 1968; First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Utah School for the Deaf 100th Year Anniversary Alumni Reunion, 1984).

The Extension Division, established in 1959, was successful and expanded from one to over twenty classrooms in Salt Lake City, Ogden, Provo, Brigham City, Logan, and Vernal from 1961 to 1970. As part of its outreach programs, the Utah School for the Deaf collaborated with various public schools in different areas. The Extension Division team included teachers, nursery teachers, teacher aides, consultants, volunteers, and a curriculum coordinator. The Extension Division offered classes at preschool, kindergarten, elementary, junior high, and high schools (The Utah Eagle, January 1968; First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Utah School for the Deaf 100th Year Anniversary Alumni Reunion, 1984).

Since then, with the support of parents who advocated for oral education and integration into mainstream schools, the school has been a leader in mainstreaming students who are deaf or hard of hearing into local school districts all over Utah. This collective effort, along with Dr. Bitter's mission, spearheaded the mainstreaming movement and led to a significant shift in deaf education (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

The Extension Division, established in 1959, was successful and expanded from one to over twenty classrooms in Salt Lake City, Ogden, Provo, Brigham City, Logan, and Vernal from 1961 to 1970. As part of its outreach programs, the Utah School for the Deaf collaborated with various public schools in different areas. The Extension Division team included teachers, nursery teachers, teacher aides, consultants, volunteers, and a curriculum coordinator. The Extension Division offered classes at preschool, kindergarten, elementary, junior high, and high schools (The Utah Eagle, January 1968; First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Utah School for the Deaf 100th Year Anniversary Alumni Reunion, 1984).

Since then, with the support of parents who advocated for oral education and integration into mainstream schools, the school has been a leader in mainstreaming students who are deaf or hard of hearing into local school districts all over Utah. This collective effort, along with Dr. Bitter's mission, spearheaded the mainstreaming movement and led to a significant shift in deaf education (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the Salt Lake area, the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf also accepted children with disabilities who could learn academically as young as two and a half years old. After preschool, Deaf students would either transfer to Ogden's residential campus or continue their education in the Extension Oral Program. Curriculum coordinators, instructors, and parents collaboratively made the placement decision, considering the student's academic performance, home environment, and social development. In most cases, students transitioned from preschool to kindergarten. If a student made good progress in all areas, they would remain under the supervision of the Extension Division until high school graduation. If they needed more intensive speech and listening training, the Extension Division could transfer them to the Ogden residential campus due to insufficient sections at each grade level in the Extension Division to accommodate a wide deviation in performance in these oral skills (The Utah Eagle, January 1968).

The Oral and Mainstreaming

Movement is Flourishing in Utah

Movement is Flourishing in Utah

Persuaded to come out of retirement, Mary Burch taught the first extension classroom in Salt Lake City in September 1959. Originally from Kentucky, she taught at Clarke School for the Deaf, a private oral-deaf school in Northampton, Massachusetts. The extension classroom was considered a success for the school year from September 1959 to May 1960 (Tegedar, The Utah Eagle, October 1959; The Utah Eagle, October and November 1960).

As a result of its success, the number of classrooms expanded. In 1960, the Utah School for the Deaf added two more extension classrooms to Riley Elementary School in Salt Lake City, Utah. The goal was to assess the effectiveness of teaching Deaf children speech and listening skills. Teachers on this project advocated for and taught oral instruction in the classroom. To ensure and promote the program's success, the teachers wanted to include parents and invited them to observe the class during the experiment. They hoped to gain parental support and use it to push their agenda (Ronald Burdett, personal communication, 2009).

As an example of mainstreaming expansion, Dr. Bitter taught the first integrated class for oral students at Jordan Middle School, Salt Lake City School District, in cooperation with the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf from 1962 to 1964. Following his doctorate, the Extension Division promoted him to Curriculum Coordinator, a role he held for two years from 1967 to 1969 (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

For the first time in history, Utah established certification standards for deaf education teachers in 1958 (The Utah Eagle, April 1958). In 1962, Reid C. Miller, an oral advocate, assistant professor, and director, established the Teacher Training Program under the Speech Pathology and Audiology Department at the University of Utah, focusing primarily on oral education through a collaboration between the University of Utah and the Utah School for the Deaf (Tony Christopulos, personal communication, November 5, 1986; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). The Department of Special Education later took over the Teacher Training Program in 1967 to help prepare future oral education teachers, known as an 'army of oral teachers,' for employment at the Utah School for the Deaf (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Bitter, Utah's Hearing Impaired Children...At High Risk, 1986). At the time, university policy changed, requiring doctorates for program directors at this level. The university let go of Reid C. Miller, who held a master's degree, and hired Dr. Bitter, who was the Curriculum Coordinator of the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf, in 1968, to become an Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the Teacher Training Program in 1968 after he completed his doctorate in 1967 (Utah Eagle, October 1967; Boyack, David County, 1970; Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). From 1968 to 1969, he had two hats for a year, working as the Extension Division Coordinator and professor of the Teacher Training Program. He resigned as an Extension Division coordinator and continued teaching the Teacher Training Program until his retirement in 1987 (Bitter, Utah's Hearing Impaired Children...At High Risk, 1986; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

For the first time in history, Utah established certification standards for deaf education teachers in 1958 (The Utah Eagle, April 1958). In 1962, Reid C. Miller, an oral advocate, assistant professor, and director, established the Teacher Training Program under the Speech Pathology and Audiology Department at the University of Utah, focusing primarily on oral education through a collaboration between the University of Utah and the Utah School for the Deaf (Tony Christopulos, personal communication, November 5, 1986; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). The Department of Special Education later took over the Teacher Training Program in 1967 to help prepare future oral education teachers, known as an 'army of oral teachers,' for employment at the Utah School for the Deaf (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Bitter, Utah's Hearing Impaired Children...At High Risk, 1986). At the time, university policy changed, requiring doctorates for program directors at this level. The university let go of Reid C. Miller, who held a master's degree, and hired Dr. Bitter, who was the Curriculum Coordinator of the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf, in 1968, to become an Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the Teacher Training Program in 1968 after he completed his doctorate in 1967 (Utah Eagle, October 1967; Boyack, David County, 1970; Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). From 1968 to 1969, he had two hats for a year, working as the Extension Division Coordinator and professor of the Teacher Training Program. He resigned as an Extension Division coordinator and continued teaching the Teacher Training Program until his retirement in 1987 (Bitter, Utah's Hearing Impaired Children...At High Risk, 1986; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

For deaf education, the University of Utah provided licensed teachers with an emphasis on speaking and listening skills, whereas the Utah School for the Deaf provided student teaching facilities, internships, and daily on-site supervision for its student teachers (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985). However, the Special Education Department did not plan any such Teacher Training Program for prospective teachers who would teach Deaf students in sign language using the simultaneous communication method. The state board did not resolve this issue until 1984 (Utah, 1973; Campbell, 1977; Bitter, Utah's Hearing Impaired Children...At High Risk, 1986).

From there, Dr. Bitter incorporated his oral and mainstreaming philosophy into the curriculum for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. His daughter Colleen, who was Deaf, was born in 1954, and he wanted her to be able to speak. His ambition led him to play a key role in developing the oral teaching method. At that time, this was the only program for training deaf education teachers in Utah. The main goal of this program was to train future teachers to teach Deaf children to speak and listen in the same way as hearing children. The curriculum focused solely on the oral method and did not include sign language training. In the UAD Spring 1964 Bulletin, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson stated that the University of Utah prioritized oral instruction in deaf education. The university also attracted teachers trained in the oral instruction approach; many came from well-known oral deaf schools, such as Clarke School for the Deaf and Lexington School for the Deaf. The Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah quickly produced teachers of oral and mainstream education.

The curriculum focused solely on the oral method and did not include sign language training. In the UAD Spring 1964 Bulletin, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson stated that the University of Utah prioritized oral instruction in deaf education. The university also attracted teachers trained in the oral instruction approach; many came from well-known oral deaf schools, such as Clarke School for the Deaf and Lexington School for the Deaf. The Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah quickly produced teachers of oral and mainstream education.

Dr. Sanderson was not the only one who saw the effects of having so many oral teachers at the Utah School for the Deaf. Both Dr. Jay J. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a sign language interpreter, the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, and a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community, along with Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, Curriculum Coordinator of the Total Communication Division at the Utah School for the Deaf, observed the impact on the school. 90% of Deaf children have hearing parents, so they became advocates for the oral and mainstreaming movements. Many hearing parents were unfamiliar with sign language and wanted their Deaf child to learn how to speak (Baldwin, 1975, p. 1; Campbell, 1977). Most Deaf adults preferred simultaneous communication, which included signs in classroom instruction. The University of Utah rejected the Utah Association for the Deaf's request for the Teacher Training Program to incorporate simultaneous communication methods into their curriculum (Campbell, 1977).

In the late 1960s and 1970s, there was a national shift in deaf education, moving away from the oral method and towards an approach that included sign language, known as Total Communication. In 1960, Dr. William Stokoe, a scholar and hearing professor at Gallaudet College, published a dissertation recognizing American Sign Language (ASL) as an official language with its own syntax, morphology, and structure (Wikipedia: William Stokoe). Despite Dr. Stokoe's research, many professionals in Utah's deaf education field continued to advocate for the oral approach, and the University of Utah's Teacher Training Program did not include sign language.

A Protest at the University of Utah

In 1971, the Utah Association for the Deaf, including Lloyd H. Perkins, Chairperson of the UAD Educational Committee, asked in writing for a review of the Teacher Training Program (L. Perkins, personal communication, no date). On December 7, 1971, Dr. Erdman, the Department of Special Education Chairperson, wrote back to affirm to Lloyd that there would be a meeting on December 13 to review the Teacher Training Program. Dr. Stephen Hencley, the Dean of the Graduate School of Education, responded to Lloyd's letter on December 16, 1971, assuring him that the Teacher Training Program would undergo curriculum changes and incorporate a sign language component (Dr. Erdman, personal communication, December 6, 1971).

Four years later, on July 23, 1974, Dr. Jay J. Campbell followed up with Dr. Erdman, the Chairperson of the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. He requested a report to confirm the implementation of a comprehensive communication curriculum in the Teacher Training Program. In response, Dr. Erdman informed Dr. Campbell that the Teacher Training Program hired Gene Stewart, a Children of Deaf Adults (CODA) and vocational rehabilitation counselor, in 1972 to teach a sign language course. Dr. Erdman's letter also included the new policy, as stated: "All students who are preparing to become teachers of the hearing impaired are required to master the basic manual communication competencies through involvement in one or both of the above described classes or be able to demonstrate those competencies if they have already had previous manual communication experiences and/or coursework in that area" (Dr. Erdman, personal communication, p. 2, August 15, 1974). There was a divergence between the Deaf Association for the Deaf and the Special Education Department regarding the extent to which the program would offer total communication courses. Apparently, the Utah Association for the Deaf expected a complete Total Communication Program, but the Teacher Training Program disagreed with this expectation.

In 1977, the Utah Association for the Deaf continued to advocate for including a total communication curriculum in their program. They urged University President Alfred C. Emery and other administrators to review the Teacher Training Program, modify the curriculum, and include sign language as an equal component of oralism. In late August or early September 1977, UAD representatives met with Dr. Pete D. Gardner, Vice President for Academic Affairs at the University, to present a 9-point list of concerns regarding the Teacher Training Program, as shown in the section below. During the meeting, Lloyd Perkins and other UAD representatives requested to meet with President Emery to present their concerns. However, Dr. Gardner responded by sending a letter to Lloyd Perkins' wife, Madeleine Burton Perkins, who served as an interpreter for the meeting. In the letter, Dr. Gardner informed them that a meeting with President Emery would be unproductive and that Dr. Bitter had not violated any academic standards (P.D. Gardner, personal communication, September 14, 1977).

President Emery's refusal to meet sparked controversy when W. David Mortensen, a well-known political activist and president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, organized two protests. The first protest took place on November 18, 1977, outside the Utah State Office of Education, and the second on November 28, 1977, in front of the Park Building on the University of Utah campus. The protests were held because the University of Utah provided an unequal oral and total communication training program, favored oral-only education, was biased against using the total communication method of teaching, favored day schools, had no Deaf representative on the Advisory Committee, and failed to listen to UAD and the Utah Deaf community on a regular basis. On November 28, approximately twenty Deaf people gathered in front of the Park Building to protest the university's handling of their concerns. M. J. Lewis published a letter to the Deseret News, stating that "Dr. Bitter has so brainwashed and put fear into parents that their children will never be able to function as normal human beings" (Lewis, Deseret News, November 28, 1977; Jeff Pollock, The Utah Deaf Education Controversy, May 4, 2005).

During the protest, Dr. Bitter's still stance on how Deaf students should be educated in oralism and his rejection of the Utah Association for the Deaf's demand to include sign language in his curriculum. In response to the Utah Association for the Deaf protest, Dr. Bitter said, "We are trying to be fair and meet individual needs" (Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, November 29, 1977, p. 1; Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, December 2, 1977). He responded that he supported an oral-only approach because he believed it was the most effective way to help Deaf children integrate into society (Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, November 29, 1977, p. 1).

Dr. Bitter further contended that oralism would help Deaf children develop a positive self-concept and prepare them for mainstream life independently without relying on a sign language interpreter. He further clarified that the Teacher Training Program included sign language classes. Dr. Bitter noted that the university had met its obligations to the Utah State Board of Education by incorporating total communication opportunities in its oral curriculum (Graduate School of Education, November 28, 1977; Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, December 2, 1977).

The protests, led by UAD President Mortensen, caught the attention of the Utah State Board of Education. In April 1979, they passed a motion directing the University of Utah to hire a faculty member to teach a total communication class to prospective deaf education teachers (The Silent Spotlight, June 1979; Jeff Pollock, The Utah Deaf Education Controversy, May 4, 2005). More details about the protest can be found in "The Utah Deaf Education Controversy: Total Communication and Oralism at the University of Utah." From 1979 to 1985, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson taught ASL (then total communication) as well as the social, psychological, and cultural aspects of deafness as an adjunct professor in the Division of Communication Disorders at the University of Utah (Newman, 2006).

Dr. Bitter revealed in an interview with the University of Utah in 1987 that he had been the target of a vicious attack by the Utah Deaf community. Community leaders viewed him as a scoundrel who knew nothing about deafness. During this time, picketers gathered on the University of Utah campus and at the Utah State Office of Education, staging protests that included burning his effigy. The "Years of Controversy" paper also contains slanderous statements, detailed in Jeffrey W. Pollock's paper, like, "Jay J. Campbell will put Burbank down. Power is UAD" and "J.J. Campbell and R. Sanderson will throw Boyd Nielsen out of job in Utah, in America, and out of this world. UAD is Deaf power" (Grant Bitter, Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). It is clear that Dr. Bitter had little understanding of Deaf people's experiences in the oral and mainstreaming educational system. If only he had listened to their perspectives and understood what Deaf people went through.

Dr. Bitter revealed in an interview with the University of Utah in 1987 that he had been the target of a vicious attack by the Utah Deaf community. Community leaders viewed him as a scoundrel who knew nothing about deafness. During this time, picketers gathered on the University of Utah campus and at the Utah State Office of Education, staging protests that included burning his effigy. The "Years of Controversy" paper also contains slanderous statements, detailed in Jeffrey W. Pollock's paper, like, "Jay J. Campbell will put Burbank down. Power is UAD" and "J.J. Campbell and R. Sanderson will throw Boyd Nielsen out of job in Utah, in America, and out of this world. UAD is Deaf power" (Grant Bitter, Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). It is clear that Dr. Bitter had little understanding of Deaf people's experiences in the oral and mainstreaming educational system. If only he had listened to their perspectives and understood what Deaf people went through.

A New Deaf Education Program

at Utah State University

at Utah State University

On April 20, 1982, Utah State University approved a new deaf education major, marking a significant milestone in Utah's history of deaf education. This major allowed teacher candidates to study total communication skills, a crucial aspect of deaf education. Leading this program was Dr. Thomas C. Clark, the founder of SKI-HI, which served Deaf babies and toddlers.He, a professor and mentor, dedicated his life to training teachers and parent advisors who could meet the needs of Deaf children and their families. Dr. Clark was a pioneer of deaf education and early intervention services for Deaf children in the nation. He knew that early access to language was crucial for Deaf children's success, so he developed programs that provided services to the families of Deaf children in their homes. He founded the SKI*HI Institute at Utah State University, which has become the model for early home intervention programs for Deaf children and children with disabilities in the United States and around the world (UAD Bulletin, April 2010).

He was the hearing son of a Deaf father, John H. Clark, who graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1897 and became the first Utah graduate of Gallaudet College in 1902. Dr. Thomas C. Clark was also the second cousin of Elizabeth DeLong, who, also like John H. Clark, also graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1897, the first Utah graduate from Gallaudet College in 1902, and the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf in 1909. However, it's important to note that funding was unavailable until 1985, when Utah State University established a preparation program to provide a total communication component.

Duane Kinner, the son of Deaf parents Kenneth and Ilene Kinner, was featured on the front cover of the SKI-Hi Model packet in 1974. The packet provided training through amplification and home intervention when visiting families with Deaf infants and toddlers.

Launching a Total Communication Program at Utah State University was a huge step forward for the Utah Association for the Deaf and the Utah Deaf community! Previously, the majority of total communication teachers in Utah were from other states, while the majority of oral teachers came from the University of Utah. In 1991, Dr. J. Freeman King, a newly hired hearing professor, transformed the Deaf Education Program at Utah State University from a Total Communication Program to a Bilingual-Bicultural Program (UAD Bulletin, October 1991).

In 2007, Dr. Karl R. White, a psychology professor at Utah State University, led the establishment of the Listening and Spoken Language program. Initially, this led to a heated debate between the Bilingual-Bicultural Program and the Listening and Spoken Language Program. Nonetheless, they coexisted and focused on their work within the same department.

The Utah School for the Deaf Is Not

Comparable to Traditional Residential Schools

Comparable to Traditional Residential Schools

Over the years, Dr. Bitter has strongly advocated oralism and mainstreaming. The decline of education at the Utah School for the Deaf, as well as the integration of more Deaf students into mainstream education, saddened its alums. In Utah, the oral and mainstreaming movements have influenced deaf education since the early 1960s, with Dr. Bitter playing a pivotal role. He used his influence and parental power to promote oralism in deaf education, making it difficult for the Utah Association for the Deaf to challenge him. After the Teacher Training Program in the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah closed in 1986, Dr. Bitter retired in 1987 (Bitter, A Summary Report for Tenure, March 15, 1985). Today, the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah offers a Specialization in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program. While the curriculum does include American Sign Language classes, it still places a greater emphasis on listening and speaking. This reflects the impact that Dr. Bitter, who passed away in 2000, continues to have on deaf education in Utah. To learn more about the evolving mainstreaming movement, visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective' webpage.

In 2001, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a member of the USDB Institutional Council at the time, observed that Utah took a different approach to deaf education compared to other states, where residential schools were the norm. Instead of having children attend school on campus, Utah prioritized mainstreaming. This resulted in the integration of most Deaf children into public schools, with only a small number of students residing on campus. The Utah School for the Deaf also implemented self-contained classes led by its personnel staff in the local public school system to further integrate Deaf and hard of hearing students (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, April 2001; Sanderson, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 13, 2001).

According to Dr. Sanderson, 90% of the Deaf and hard of hearing students

were scattered throughout Utah in various school districts. These students registered at the Utah School for the Deaf, a specialized institution that meets the educational needs of Deaf and hard of hearing students. The Utah School for the Deaf also provided educational and consulting services to non-USD students who were Deaf and hard of hearing. The expertise of USDB benefited public school district service providers and families of Deaf and hard of hearing students. As a result, Utah designated the Utah School for the Deaf as a state institutional resource, providing expertise to any educational programs that served Utah's Deaf and hard of hearing children (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, April 2001; McAllister, 2002).

In 2001, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a member of the USDB Institutional Council at the time, observed that Utah took a different approach to deaf education compared to other states, where residential schools were the norm. Instead of having children attend school on campus, Utah prioritized mainstreaming. This resulted in the integration of most Deaf children into public schools, with only a small number of students residing on campus. The Utah School for the Deaf also implemented self-contained classes led by its personnel staff in the local public school system to further integrate Deaf and hard of hearing students (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, April 2001; Sanderson, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 13, 2001).

According to Dr. Sanderson, 90% of the Deaf and hard of hearing students

were scattered throughout Utah in various school districts. These students registered at the Utah School for the Deaf, a specialized institution that meets the educational needs of Deaf and hard of hearing students. The Utah School for the Deaf also provided educational and consulting services to non-USD students who were Deaf and hard of hearing. The expertise of USDB benefited public school district service providers and families of Deaf and hard of hearing students. As a result, Utah designated the Utah School for the Deaf as a state institutional resource, providing expertise to any educational programs that served Utah's Deaf and hard of hearing children (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, April 2001; McAllister, 2002).

The approach to deaf education in Utah differed from that of other states in several ways. Initially, the Utah State Office of Education and the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind interpreted the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Public Law 94-142, to mean that the least restrictive environment (LRE) for these students would be a mainstream public school. The Utah School for the Deaf primarily focused on the oral method of instruction, reflecting this viewpoint. However, a problem arose when the Individualized Education Program (IEP) team considered educational placement options in Utah and other states. Unlike other states, Utah commonly refers to the LRE as a regular school classroom.

Despite Utah's LRE interpretation, Lawrence M. Siegel, a special education attorney specializing in deaf education, noted in 2000 that a Deaf or hard of hearing student's educational placement decision should be based on communication-driven factors. The student's preferred mode of communication, a deeply personal and integral part of their identity, should be given utmost consideration. This prioritization would undoubtedly impact the outcome of the IEP placement decision. The more pressing question would be whether the student's school environment could provide them with an accessible language and equal communication opportunities. According to Lawrence, this was not just a matter of educational rights but of fundamental human rights. Deaf and hard of hearing students, according to Lawrence, have the same universal need for language and communication as any other human being. This fundamental requirement should be the starting point for all educational decisions. The deaf school made poor decisions by enrolling a Deaf or hard of hearing student in the public school system, expecting it to be the least restrictive environment. The IEP paperwork is a legal document that enforces all placement and goal determinations. The IEP team should research the student's language accessibility needs before making placement decisions (National Deaf Education Project).

Despite Utah's LRE interpretation, Lawrence M. Siegel, a special education attorney specializing in deaf education, noted in 2000 that a Deaf or hard of hearing student's educational placement decision should be based on communication-driven factors. The student's preferred mode of communication, a deeply personal and integral part of their identity, should be given utmost consideration. This prioritization would undoubtedly impact the outcome of the IEP placement decision. The more pressing question would be whether the student's school environment could provide them with an accessible language and equal communication opportunities. According to Lawrence, this was not just a matter of educational rights but of fundamental human rights. Deaf and hard of hearing students, according to Lawrence, have the same universal need for language and communication as any other human being. This fundamental requirement should be the starting point for all educational decisions. The deaf school made poor decisions by enrolling a Deaf or hard of hearing student in the public school system, expecting it to be the least restrictive environment. The IEP paperwork is a legal document that enforces all placement and goal determinations. The IEP team should research the student's language accessibility needs before making placement decisions (National Deaf Education Project).

Utah Code 53A-25-104: The Culprit

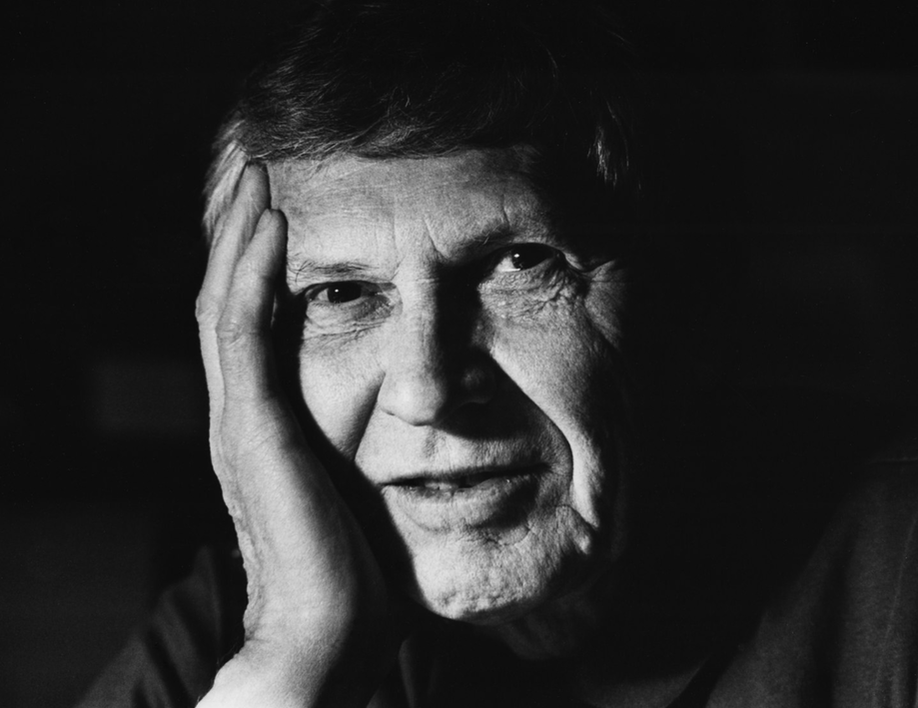

Since the passage of Public Law 94-142 in 1975, the Deaf community has viewed the public school system as the "most restrictive environment" for many Deaf students. The mainstreaming inclusion of more Deaf children led to their isolation from their peers and a lack of Deaf adult role models. This resulted in language and social deprivation due to an inability to learn American Sign Language in their public school years (Erting et al., 1989). The Utah Association for the Deaf recognized that the mainstreaming philosophy and prevalent oral teaching methods at the Utah School for the Deaf had influenced mainstreamed placement decisions. During an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) meeting, Bronwyn O'Hara, a hearing parent, her daughter Ellen, age 9, Steven Noyce, an oral and mainstreaming advocate, and the Outreach Program Director of the Utah School for the Deaf revealed the true nature of deaf education in Utah.

In the fall of 1994, Bronwyn, who became friends with Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, a Deaf renowned leader and future co-founder of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, advocated the development of a day school for Deaf students where they could be together and share a common language and culture. In this place, hearing parents could learn from Deaf adults, and Deaf adults would feel valued. Bronwyn wanted this for all Deaf children and families. She formed the Support Group for Deaf Education with this goal in mind and planned to educate other parents of Deaf children about deaf issues and deaf education. She has three Deaf children and understands the importance of receiving accurate information to make informed decisions. At the IEP meeting, Steven Noyce stated that the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind, under the Special Education Department, could not establish a deaf day school. He also noted that we would need to change the Utah Code, which regulates USDB, if we wanted a day school (O'Hara, UAD Bulletin, January 1995). Steven Noyce's insight reinforced information Bronwyn had obtained a few years prior during a phone conversation with Steve Kukic, the State Director of Special Education at the time. He informed her that all Deaf students began their education at the Department of Special Education rather than in regular schools. As a result, Utah law established specific rules to follow.

Bronwyn's plea during the 1994 IEP meeting sparked a dialogue with Steven Noyce. She requested that Ellen communicate in ASL directly with teachers and peers without using an interpreter, and she also needed peers with communication and linguistic abilities comparable to her own. Steven Noyce noted at the time that the law prohibited grade-level or above-grade-level Deaf students from attending the Utah School for the Deaf and its self-contained classes. He continued, "The classification of all Deaf children as special education students limited Ellen's educational options." Bronwyn was stunned. She asked where the intelligent Deaf students went. He replied with a single word: 'Mainstreamed' (Bronwyn O'Hara, personal communication, August 27, 2009).

Bronwyn's plea during the 1994 IEP meeting sparked a dialogue with Steven Noyce. She requested that Ellen communicate in ASL directly with teachers and peers without using an interpreter, and she also needed peers with communication and linguistic abilities comparable to her own. Steven Noyce noted at the time that the law prohibited grade-level or above-grade-level Deaf students from attending the Utah School for the Deaf and its self-contained classes. He continued, "The classification of all Deaf children as special education students limited Ellen's educational options." Bronwyn was stunned. She asked where the intelligent Deaf students went. He replied with a single word: 'Mainstreamed' (Bronwyn O'Hara, personal communication, August 27, 2009).

Unwilling to give up, Bronwyn pleaded with him to draft an IEP for Ellen, including gifted student goals, to enable her to receive an education at or above the grade level at the Utah School for the Deaf. Bronwyn was determined to overcome obstacles by circumventing existing laws to achieve her goal for Ellen, similar to how some states fund their gifted programs more efficiently by placing gifted students in special education without a waiver. However, Steven shrugged and remarked that it would not happen in Utah. He continued by stating that changing the law would be necessary for the situation to change (Bronwyn O'Hara, personal communication, August 27, 2009).

Deaf student Toni Ekenstam gets auditory training from Steven Noyce, a teacher of the deaf. Toni is taught to lip read and communicate with her own voice, one of several methods used to teach deaf children at the Utah School for the Deaf @ Deseret News, March 8, 1973. Deseret News Photo by Chief Photographer Don Groyston

Bronwyn realized there were no alternatives but to mainstream Ellen in a public school. Having lived in Utah for eight years, Bronwyn suspected that parents had never discussed or clarified many USDB educational regulations. She also believed she had obtained enough information through reading, phone calls, and questioning at her children's IEP meetings. Nonetheless, when Bronwyn requested answers, the USDB officers responded vaguely. Following the eye-opening IEP meeting, Bronwyn warned the Utah Association for the Deaf and its Deaf Community about the law that governs the USDB. She believed they deserved to know what prevented the state from improving deaf education (Bronwyn O'Hara, personal communication, April 27, 2009). The UAD Bulletin published her letter on the third page, requesting their assistance in changing the law in the January 1995 issue, as shown in the section below.

Bronwyn O'Hara Writes a Letter

to the Utah Deaf Community

to the Utah Deaf Community

Dear Editor,

Right now, the law says that THE UTAH SCHOOLS FOR THE DEAF AND THE BLIND IS UNDER SPECIAL EDUCATION. BECAUSE OF THAT RESTRICTION, THE ONLY DEAF CHILDREN WHO QUALIFY FOR ATTENDING USDB ARE THOSE WHO WOULD QUALIFY FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION…

Does the Deaf community understand what this means?? This means that the deaf children who attend USDB must have delays in some area and need remedial help. This means the intelligent deaf children, on grade level or above, CAN NOT attend USDB. If they do attend USDB, they either are mainstreamed as much as possible or receive a remedial education with the rest of the remedial students (‘Remedial’ means “a special course to help students overcome deficiencies”).

The only way for deaf children to be educated together and for the possibility for a Day school is to CHANGE THE LAW. We need the Deaf community’s political clout to accomplish this. Please help! You accomplished so much last legislative session. You need to do it again.

Sincerely,

Bronwyn O’Hara, Parent

(O’Hara, UAD Bulletin, January 1995, p. 3)

Right now, the law says that THE UTAH SCHOOLS FOR THE DEAF AND THE BLIND IS UNDER SPECIAL EDUCATION. BECAUSE OF THAT RESTRICTION, THE ONLY DEAF CHILDREN WHO QUALIFY FOR ATTENDING USDB ARE THOSE WHO WOULD QUALIFY FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION…

Does the Deaf community understand what this means?? This means that the deaf children who attend USDB must have delays in some area and need remedial help. This means the intelligent deaf children, on grade level or above, CAN NOT attend USDB. If they do attend USDB, they either are mainstreamed as much as possible or receive a remedial education with the rest of the remedial students (‘Remedial’ means “a special course to help students overcome deficiencies”).

The only way for deaf children to be educated together and for the possibility for a Day school is to CHANGE THE LAW. We need the Deaf community’s political clout to accomplish this. Please help! You accomplished so much last legislative session. You need to do it again.

Sincerely,

Bronwyn O’Hara, Parent

(O’Hara, UAD Bulletin, January 1995, p. 3)

Bronwyn refused to postpone Ellen's education until the law underwent a change. So, the O'Hara family decided to leave Utah when it became clear that the current statute was a roadblock. Bronwyn had reservations about mainstreaming her Deaf children, as it would deprive them of Deaf adults and peers in terms of education and socialization. Ellen had an ineffective interpreter in fourth grade at Scera Park Elementary School, where she spent some of her time mainstreaming. In the Utah School for the Deaf system, there was no way to get a better one. These circumstances consistently hindered her child's academic advancement. In reality, squandering these years of education was irreversible. The family decided it was time to find a school that aligned with their values. In 1995, Ellen enrolled at the Indiana School for the Deaf, which was the first state school in 1990 to incorporate the bilingual-bicultural program and its philosophy into the curriculum.

Another Parent's

Turn to Learn About the Law

Turn to Learn About the Law

Twelve years later, in 2007, it was another parent's turn to learn about Utah's law regulating Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. When I moved to Utah from Washington, D.C., in 2000, I was unaware of Bronwyn's family issues with the Utah School for the Deaf. As a Deaf parent with two Deaf children, Joshua and Danielle, in 2004, the USDB Institutional Council (later renamed the Advisory Council) elected me to serve on the council to represent the Utah Deaf community rather than as a parent. Bronwyn had also applied for a council position but was unsuccessful. While applying for a vacant position to replace Dr. Sanderson, whose term had expired, I suspected my oral and mainstreaming background led to my selection. This role as an advocate for the Utah Deaf community has given me a unique perspective and a platform to bring about change.

When I enrolled my Deaf children, Joshua and Danielle, at the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, a part of the Utah School for the Deaf, I encountered the culprit of the Utah Code, which governed the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. Before the 2005 USD/JMS merger, Joshua's enrollment at JMS, an independent charter school at the time, was easy when he turned three in 2004. Therefore, there was no barrier for him to be notified of his service through the local school district. However, JMS had to comply with Utah's Special Education and IDEA regulations after the 2005 merger. Before registering at the Utah School for the Deaf, these regulations mandated a family's referral to their local school district. Like Joshua, I had also decided to place my daughter, Danielle, who turned three in 2006, in JMS after the merger. Her evaluation testing was part of the IDEA process, requiring her to undergo a lengthy procedure. The IEP meeting revealed that Danielle was six months behind her hearing peers in school, which qualified her for educational services at JMS. I asked if Danielle would be eligible to attend JMS if she was academically on par with her peers. She wouldn't, according to the IEP team. When I pressed for further information, I was met with vague responses, and as with most parents before me, I let the questions slide. In that one IEP meeting, there was no way I could get to the bottom of the USDB system.

When I enrolled my Deaf children, Joshua and Danielle, at the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, a part of the Utah School for the Deaf, I encountered the culprit of the Utah Code, which governed the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind. Before the 2005 USD/JMS merger, Joshua's enrollment at JMS, an independent charter school at the time, was easy when he turned three in 2004. Therefore, there was no barrier for him to be notified of his service through the local school district. However, JMS had to comply with Utah's Special Education and IDEA regulations after the 2005 merger. Before registering at the Utah School for the Deaf, these regulations mandated a family's referral to their local school district. Like Joshua, I had also decided to place my daughter, Danielle, who turned three in 2006, in JMS after the merger. Her evaluation testing was part of the IDEA process, requiring her to undergo a lengthy procedure. The IEP meeting revealed that Danielle was six months behind her hearing peers in school, which qualified her for educational services at JMS. I asked if Danielle would be eligible to attend JMS if she was academically on par with her peers. She wouldn't, according to the IEP team. When I pressed for further information, I was met with vague responses, and as with most parents before me, I let the questions slide. In that one IEP meeting, there was no way I could get to the bottom of the USDB system.

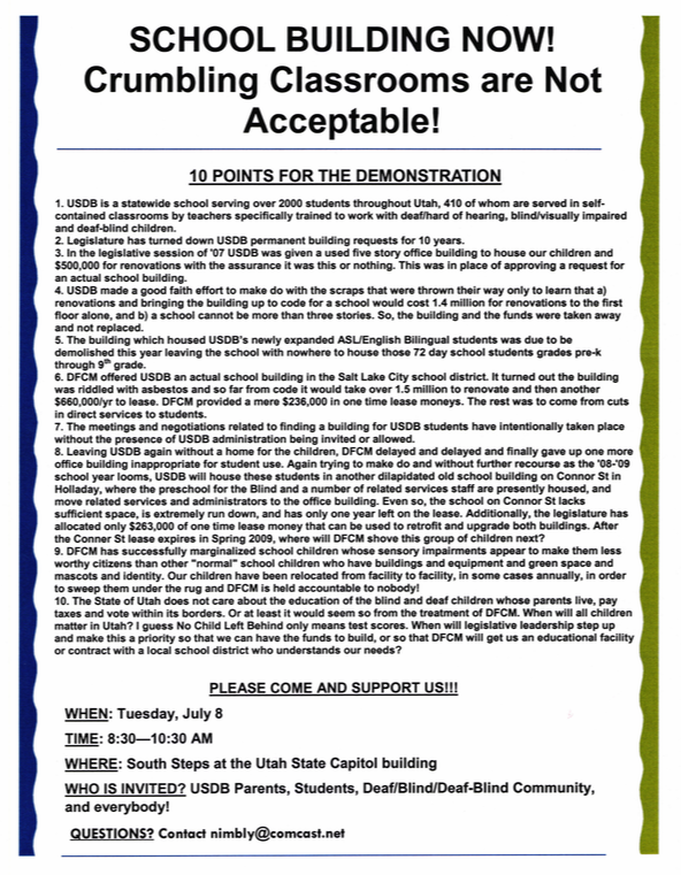

A year later, in 2007, it surfaced again when Joshua's yearly evaluation report arrived. During the IEP meeting, I learned that, as a kindergartener, he was just one point away from being mainstream. I was stunned to learn that every student scoring 85 or higher at the USDB had been "kicked out" since the late 1970s, following the passage of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in 1975. This also affected students with Low Vision, Blind, or DeafBlind. The school transferred students who performed well on standardized tests to a public school. As a member of the Utah Deaf Education and Literacy Board of the JMS Charter School, we anticipated the JMS would flourish after the merger, but the reverse happened. In 2006, JMS shrank one year after the merger, losing several bright students to mainstreaming. Some had also transferred to a deaf state school outside the state. Like the Utah School for the Deaf, JMS went through the same cycle of losing intelligent students and struggling with retention. It was Catch-22 all over again. Julio Diaz, Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, and I, the JMS Deaf parents, couldn't figure out the root of the problem until the Utah School for the Deaf administration revealed the reasons behind the Utah Code. What we learned about the Utah Code governed USDB shocked us. Utah Code 53A-25-104 [Code 53A-25-104(2)(a) and (b)] mandated determining the eligibility of hearing-impaired children, as they called it, for special education services before drafting an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and allowing them to attend the Utah School for the Deaf. Yet Utah Code 25A-25-103 declares, in its definition of the Utah School for the Deaf, that USD can educate all of the deaf and hearing-impaired children in the state. We noticed these two laws contradicted each other (Utah State Legislature: Utah Code 53A-25-104 and Utah Code 25A-25-103).

I soon realized that the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind were required by law to identify Deaf and hard of hearing students as special education students if they demonstrated academic delays and that an Individualized Education Program (IEP) was required for special education services and placement. Only students with special needs or those experiencing academic delays received services at USDB, a special education school. If these students experienced academic delays, they would need an IEP. However, the issue of Deaf students at or above grade level being ineligible for IEP services and unable to attend the USDB classes was not being adequately addressed. This issue, which Bronwyn first identified many years ago, was resurfacing. Under the USDB's umbrella, the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, a crucial institution for education, linguistics, and socialization, was forced to remove a grade-level Deaf or hard of hearing student from its environment. This was not a sustainable solution. Moreover, the decision to send Utah School for the Deaf students to a mainstream program would severely limit their access to numerous aspects of education due to communication barriers. It was clear that changes in the Utah Code's goal of promoting mainstreaming were urgently needed to avoid these catch-22 issues.

Minnie Mae was aware of the regulations because Bronwyn, whom Minnie Mae mentored during her battle with the deaf educational system, had previously worked with the USDB's Utah Code before moving to Indiana. She did not, however, recognize the connection between the consequences of the 2005 USD/JMS merger and the root of the problem until it hit home. She discovered how contradictory they were. Like me, she saw the legislation's impact on her daughter Briella's IEP meeting. Briella's exceptional academic progress prompted the IEP team to notify Minnie Mae that her daughter would no longer be eligible for services at JMS. She was startled to learn that her daughter could not continue her education at JMS. In short, JMS had to give up its autonomy in accepting Deaf and hard of hearing children from around the state in return for being governed by the Utah Department of Special Education and its laws.

I soon realized that the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind were required by law to identify Deaf and hard of hearing students as special education students if they demonstrated academic delays and that an Individualized Education Program (IEP) was required for special education services and placement. Only students with special needs or those experiencing academic delays received services at USDB, a special education school. If these students experienced academic delays, they would need an IEP. However, the issue of Deaf students at or above grade level being ineligible for IEP services and unable to attend the USDB classes was not being adequately addressed. This issue, which Bronwyn first identified many years ago, was resurfacing. Under the USDB's umbrella, the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, a crucial institution for education, linguistics, and socialization, was forced to remove a grade-level Deaf or hard of hearing student from its environment. This was not a sustainable solution. Moreover, the decision to send Utah School for the Deaf students to a mainstream program would severely limit their access to numerous aspects of education due to communication barriers. It was clear that changes in the Utah Code's goal of promoting mainstreaming were urgently needed to avoid these catch-22 issues.

Minnie Mae was aware of the regulations because Bronwyn, whom Minnie Mae mentored during her battle with the deaf educational system, had previously worked with the USDB's Utah Code before moving to Indiana. She did not, however, recognize the connection between the consequences of the 2005 USD/JMS merger and the root of the problem until it hit home. She discovered how contradictory they were. Like me, she saw the legislation's impact on her daughter Briella's IEP meeting. Briella's exceptional academic progress prompted the IEP team to notify Minnie Mae that her daughter would no longer be eligible for services at JMS. She was startled to learn that her daughter could not continue her education at JMS. In short, JMS had to give up its autonomy in accepting Deaf and hard of hearing children from around the state in return for being governed by the Utah Department of Special Education and its laws.