The History of

Utah Deaf Technology

Compiled & Written By Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2013

Updated in 2024

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2013

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

Over the years, technology has played a vital role in enhancing accessibility for the Deaf community in Utah. We depend on different technological tools to overcome communication barriers and ensure full participation in all aspects of life. Technological advancements have also made life much more comfortable for Deaf and hard of hearing individuals than in the past. We can now utilize various available devices to help us navigate our communication and information access needs.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in reading 'The History of Utah Deaf Technology' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in reading 'The History of Utah Deaf Technology' webpage.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Evolution of Hearing Devices

Hearing devices have evolved, from early ear trumpets to hearing aids, and have come a long way since the 17th century.

The Growth of Cochlear Implants

The first cochlear implant was invented in the 1950s. In the 1960s, the Utah Association for the Deaf (UAD) became interested in cochlear implants, and Dr. David A. Dolowitz, an otologist at the University of Utah School of Medicine, spoke about the Deafness Research Foundation Temporal Bone Bank at the UAD Convention in 1963. During the convention, UAD promoted the Temporal Bone Bank Program and assisted those who wanted to donate their temporal bones to help doctors with research to help others hear (UAD Bulletin, Spring 1963).

The Los Angeles Foundation of Otology started the cochlear implant experiment in the early 1960s with funding from Mr. and Mrs. George S. Eccles, who headed the First Security Bank of Utah. The last implant took place in 1968, but it is unclear why this was the last time (UAD Bulletin, June 1974). Three profoundly Deaf patients had tiny electric wires implanted in their inner ears, which were attached to a device that turned sound into small, complex electric currents through the skin behind the ear. These electric currents directly activate the hearing nerve, producing a sound sensation. Since then, they have remained in close contact with the three individuals who received the implants. They were examined to see if their bodies had accepted the foreign material implanted in the inner ear and to look for signs of rejection (UAD Bulletin, June 1974). The test showed that there were no rejection signs.

The Los Angeles Foundation of Otology started the cochlear implant experiment in the early 1960s with funding from Mr. and Mrs. George S. Eccles, who headed the First Security Bank of Utah. The last implant took place in 1968, but it is unclear why this was the last time (UAD Bulletin, June 1974). Three profoundly Deaf patients had tiny electric wires implanted in their inner ears, which were attached to a device that turned sound into small, complex electric currents through the skin behind the ear. These electric currents directly activate the hearing nerve, producing a sound sensation. Since then, they have remained in close contact with the three individuals who received the implants. They were examined to see if their bodies had accepted the foreign material implanted in the inner ear and to look for signs of rejection (UAD Bulletin, June 1974). The test showed that there were no rejection signs.

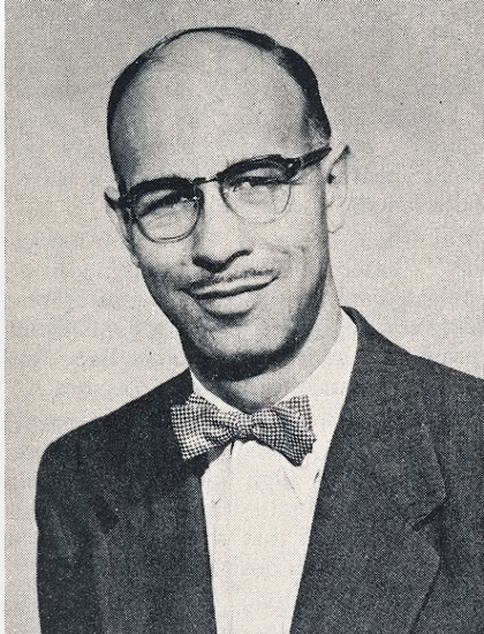

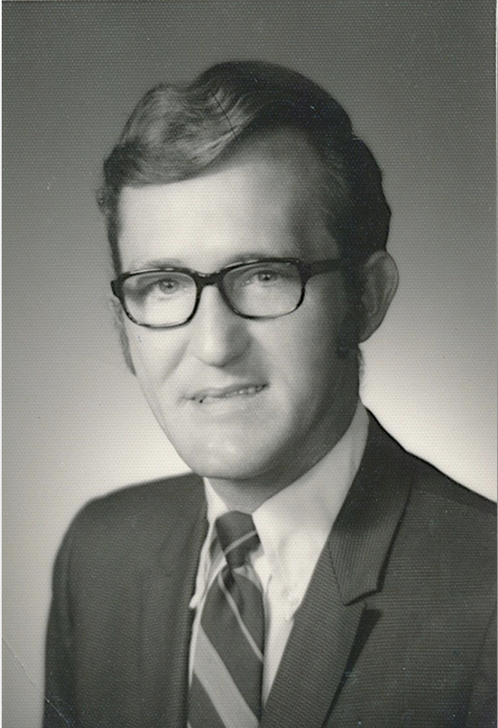

In 1974, biophysicist William H. Dobelle from the University of Utah Institute for Biomedical Engineering, in partnership with Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, head of the Utah Services of the Deaf office, launched a new initiative to advance the cochlear implant project. They contacted Deaf individuals in the Utah community, inviting them to attend an electrocochleography meeting. During the meeting, Dr. Derald E. Brackmann evaluated four volunteers - Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, W. David "Dave" Mortensen, Joseph Burnett, and his wife, LaVerne - to determine if they were suitable candidates for the implant—the evaluation involved measuring the electrical output of inner ear cells and the hearing nerve. Only Joseph Burnett was found to have functioning hearing nerves and became a volunteer candidate for the cochlear implant. The technology of cochlear implants has since evolved. During electrocochleography, a needle was inserted through the eardrum and into the inner ear bone. Sound was then used to stimulate the inner ear, and a computer measured the electrical output produced by the cells in the inner ear. If the cells were dead, there was no trace of electrical output. In that case, the hearing nerve was directly stimulated. If the sound was heard, it meant that the hearing nerve was functioning correctly (UAD Bulletin, June 1974).

In June 1974, eight Deaf individuals received cochlear implants, a groundbreaking development at the time. Five of these eight patients reported significant improvements in their hearing after using the cochlear stimulator. Two patients were still in the healing process, while one person experienced a complete restoration of their hearing through the production of electrical signals by the implanted device. This early success story highlights the transformative potential of cochlear implants (UAD Bulletin, June 1974).

In 1975, all four Utah Deaf volunteers and their interpreter, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, traveled to Los Angeles to visit the Ear Research Institute. Joseph Burnett, 62 years old at the time, received his new cochlear implant during this visit. After the surgery, he went home with wires implanted and began a series of tests with an "electronic ear." These experiments were conducted by Dr. Dobelle's Institute for Biomedical Engineering and the Ear Research Institute (UAD Bulletin, June 1975). Joseph, a true pioneer, was the first Deaf person in Utah to receive a cochlear implant following a successful surgery. This achievement was the result of a collaborative effort between the University of Utah Biomedical Center and the House Hearing Institute of California. Today, cochlear implants are being implanted more frequently in Deaf children and adults, which is a testament to the ongoing collaborative efforts in this field (Nelson, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 27, 1975).

In June 1974, eight Deaf individuals received cochlear implants, a groundbreaking development at the time. Five of these eight patients reported significant improvements in their hearing after using the cochlear stimulator. Two patients were still in the healing process, while one person experienced a complete restoration of their hearing through the production of electrical signals by the implanted device. This early success story highlights the transformative potential of cochlear implants (UAD Bulletin, June 1974).

In 1975, all four Utah Deaf volunteers and their interpreter, Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, traveled to Los Angeles to visit the Ear Research Institute. Joseph Burnett, 62 years old at the time, received his new cochlear implant during this visit. After the surgery, he went home with wires implanted and began a series of tests with an "electronic ear." These experiments were conducted by Dr. Dobelle's Institute for Biomedical Engineering and the Ear Research Institute (UAD Bulletin, June 1975). Joseph, a true pioneer, was the first Deaf person in Utah to receive a cochlear implant following a successful surgery. This achievement was the result of a collaborative effort between the University of Utah Biomedical Center and the House Hearing Institute of California. Today, cochlear implants are being implanted more frequently in Deaf children and adults, which is a testament to the ongoing collaborative efforts in this field (Nelson, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 27, 1975).

The Telecommunication System

Before the 1960s, Deaf people faced many obstacles when trying to communicate with others. They had to drive to a Deaf or hearing friend's house to meet them for business or pleasure, and they often had to rely on neighbors to make phone calls for them. If they had a telephone at home, they would ask their children to make calls for them, which could strain the parent-child relationship over time due to repeated requests (Walker, 2006).

Despite these challenges, Deaf people persevered until the launch of TTY in 1964. TTY, or Teleprinter Phonetype Units, was a way to transmit phone lines using teletype machines, like those used to send telegrams. The TTY was first demonstrated at the 1964 Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf Conference in Salt Lake City, Utah (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, September 2012).

Following the convention, Mr. Weitbrecht and Dr. Marsters founded the first TTY company. Deaf people benefited greatly from TTY, allowing them to communicate more easily with others. "TTY is catching on in many areas across the United States like wildfire," said Dennis R. Platt, president of the Utah Association for the Deaf (Platt, UAD Bulletin, Fall 1969). With TTY, Deaf individuals no longer had to rely on neighbors, friends, relatives, and their children for communication, nor did they need a car to see others. The frustration of not finding people at home was also eliminated.

In 1975, the president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, W. David Mortensen, expressed his concerns about TTY (text telephone) issues. According to national statistics, there was only one TTY for every 530 deaf people and one TTY for every hard of hearing person. In Utah, there were 78,626 people with hearing loss, including 10,225 who were deaf and 2,126 who were prevocalic deaf. However, there were only 200 TTYs in Utah, which meant that only a small percentage of Deaf people owned or used TTYs. This lack of access to telecommunications created a barrier for Deaf people, as they were unable to purchase items by calling a department store if they were deaf or if their amplification equipment was inefficient. This put them at a disadvantage compared to hearing people who had access to all the services that Deaf people did not. Estimates suggested that only one out of every two people in the United States had access to a telephone (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, October 1975, p. 2).

President Mortensen expressed his dissatisfaction with the high cost of purchasing a TTY. Unlike hearing individuals who only had to pay a small installation fee and a reasonable monthly rate for a phone that suited their style or décor, the Deaf had to pay between $250 and $600. Mortensen questioned why the Deaf should be penalized for trying to express themselves through their choice of phone style while communicating. According to Mortensen, AT&T and its operating businesses, including Mountain States Telephone, had an obligation to provide equipment to the Deaf and other customers at a cost comparable to that of ordinary telephone equipment (UAD Bulletin, October 1975, p. 2).

F.A. Caligiuri, coordinator of Deaf Community Relations at California State University, Northridge, shared Mortensen's frustration. To a Deaf person, the telephone serves as a constant reminder of their handicap and their dependence on others to use it. Caligiuri stated that the telephone also serves as an invisible barrier to their vocational advancement, as Deaf individuals are typically only considered for promotion to positions that do not require telephone use. The telephone can be a psychological barrier to the realization of their full potential. Ironically, the telephone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell to aid his deaf wife, is entirely useless to the Deaf (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, October 1975, p. 2).

The telephone company was obligated to follow the Rehabilitation Act Amendment of 1974 and the Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These acts established certain requirements to ensure that individuals with disabilities have access to and can use public buildings constructed by or on behalf of the federal government. President Mortensen pointed out that telephones were an essential part of public facilities, yet they were not accessible to Deaf people (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, October 1975, p. 2).

F.A. Caligiuri, coordinator of Deaf Community Relations at California State University, Northridge, shared Mortensen's frustration. To a Deaf person, the telephone serves as a constant reminder of their handicap and their dependence on others to use it. Caligiuri stated that the telephone also serves as an invisible barrier to their vocational advancement, as Deaf individuals are typically only considered for promotion to positions that do not require telephone use. The telephone can be a psychological barrier to the realization of their full potential. Ironically, the telephone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell to aid his deaf wife, is entirely useless to the Deaf (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, October 1975, p. 2).

The telephone company was obligated to follow the Rehabilitation Act Amendment of 1974 and the Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These acts established certain requirements to ensure that individuals with disabilities have access to and can use public buildings constructed by or on behalf of the federal government. President Mortensen pointed out that telephones were an essential part of public facilities, yet they were not accessible to Deaf people (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, October 1975, p. 2).

Between the 1970s and the 1980s, the large mailbox TTY machines were replaced by smaller, portable typewriter-style machines that could be placed on a desk or counter. The phone bill was high at that time due to the time spent typing messages on the TTY. Depending on their typing ability, some people typed slowly while others typed fast. According to a survey, even the fastest typist could not type as quickly as a person could speak over the phone (Walker, 2006).

The Enactment of Hearing Impaired

Telecommunication Access Act in Utah

Telecommunication Access Act in Utah

In 1987, the Utah Deaf Access Coalition and other organizations worked tirelessly during the legislative session to pass Senate Bill 101, known as the "Hearing Impaired Telecommunication Access Act." The bill was introduced by Senator Darrell Renstrom (D-Ogden) and aimed to improve telephone access for Deaf individuals. The bill's key features were:

To fund the telephone access program, a surcharge was to be levied on every business and household phone line in the state. The program's funds would then be used to purchase, maintain, and distribute TTYs, as well as provide training and necessary administration (UAD Bulletin, January and February 1987).

- Provision of TTYs to Deaf individuals who meet the criteria

- Establishment of a 24-hour central relay system to connect Deaf TTY users with hearing individuals

- Involvement of Deaf individuals in the program setup

- Implementation in 1987 and full service by 1989

To fund the telephone access program, a surcharge was to be levied on every business and household phone line in the state. The program's funds would then be used to purchase, maintain, and distribute TTYs, as well as provide training and necessary administration (UAD Bulletin, January and February 1987).

Deaf Supporters with Utah Governor Bangerter, 1987. It was the extended Utah Relay permit to continue in 1987 L-R: Gene Stewart, Peter Green, PSC chairman, representative from a blind organization, Lloyd Perkins, Rodney Walker, Tim Funk, Madelaine Perkins (Utah Relay director), Dave Mortensen, Jerry Westburg, Robert Bonnell and Governor Norman Bangeter sitting

The Establishment

of the Utah Relay Service

of the Utah Relay Service

In 1987, the Utah Deaf Access Coalition ran a campaign to pass Senate Bill 101. During this time, W. David Mortensen, the president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, and his Board of Directors lobbied politicians, particularly Senator Paul Fordham, to expand the Utah Relay Service. To cover the expense of Deaf phone service, the Utah State Legislature was presented with a proposal to charge each Utah citizen five cents on their phone bill. President Mortensen was concerned about the higher cost of using a phone for a Deaf person who uses a TTY. To assess the speed at which various Deaf individuals utilized the TTY, the committee working on this proposal appointed Rodney Walker, a Deaf advocate. Rodney concluded the survey and demonstrated that even the fastest typist could not type as quickly as a person could speak on the phone (Walker, 2006).

During a demonstration for legislators at the Capitol, a proficient typewriter could not keep up with a person who read a quick note. This demonstrated how much more expensive it is for a Deaf person who uses a TTY to use a phone. As a result of the demonstration, the Utah Legislature imposed a three-cent-per-month surcharge on all home and business telephone lines, also known as the "Deaf Tax." In other words, the Utah Legislature imposed a five-cent surcharge on each Utah resident's phone bill to cover the cost of the deaf phone service (UAD Bulletin, December 1988).

During a demonstration for legislators at the Capitol, a proficient typewriter could not keep up with a person who read a quick note. This demonstrated how much more expensive it is for a Deaf person who uses a TTY to use a phone. As a result of the demonstration, the Utah Legislature imposed a three-cent-per-month surcharge on all home and business telephone lines, also known as the "Deaf Tax." In other words, the Utah Legislature imposed a five-cent surcharge on each Utah resident's phone bill to cover the cost of the deaf phone service (UAD Bulletin, December 1988).

In 1988, a surcharge was implemented to fund a statewide telephone relay system that enabled Deaf, hard of hearing individuals, and people with speech limitations to communicate with hearing and speaking individuals via the conventional phone system. Additionally, the surcharge helped provide telecommunication devices to low-income individuals, allowing Deaf and hard of hearing individuals, as well as people with speech limitations, to access the telephone system directly (UAD Bulletin, December 1988).

In January 1987, the UAD organized a Telephone Access Rally, which drew 200 Deaf people to push senators to pass SB 101 during its third reading. Governor Bangerter delivered a short but moving speech during the rally, and he had already signed a proclamation declaring January 30 National Telephone Equal Access Day (UAD Bulletin, March 1987).

In January 1987, the UAD organized a Telephone Access Rally, which drew 200 Deaf people to push senators to pass SB 101 during its third reading. Governor Bangerter delivered a short but moving speech during the rally, and he had already signed a proclamation declaring January 30 National Telephone Equal Access Day (UAD Bulletin, March 1987).

After the Senate's third reading, the Utah Association for the Deaf (UAD) persisted in advocating for the passage of the bill through the House of Representatives and Governor Bangerter's signature. In March, the legislature finally enacted the Hearing Impaired Telecommunication Access Act just 20 minutes before it adjourned. To celebrate this historic occasion, UAD threw a party on May 13, 1987 (UAD Bulletin, July 1987). To commemorate the occasion, UAD threw a party on May 13, 1987 (UAD Bulletin, May 1987).

After many months of meetings, negotiations, equipment reviews, and paperwork, a new era for Utah's Deaf and Hard of Hearing community began. Nine months after the passage of SB 101, on December 18, 1987, the Utah State Board of Education approved and signed a contract with Dr. Judy Ann Buffmire, Executive Director of Rehabilitation, and David Mortensen, President of the Utah Association for the Deaf. This contract allowed for the use of a room in the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, marking a significant step forward for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community in Utah (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, January 1988).

After many months of meetings, negotiations, equipment reviews, and paperwork, a new era for Utah's Deaf and Hard of Hearing community began. Nine months after the passage of SB 101, on December 18, 1987, the Utah State Board of Education approved and signed a contract with Dr. Judy Ann Buffmire, Executive Director of Rehabilitation, and David Mortensen, President of the Utah Association for the Deaf. This contract allowed for the use of a room in the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, marking a significant step forward for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community in Utah (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, January 1988).

Deaf Supporters with Utah Governor Bangerter, 1988. Signing to permit purchase of TTYs for free distribution in 1988 Governor Norman Bangeter sitting. L-R: Lee Shepherd, Kristi Mortensen, Shanna Mortensen, Donna Lee Westberg, Tim Funk (assisted Dave Mortensen on the Hill), Ben Edwards, Craig Edwards, Roy Cochran, Senator Darrel Renstrom, D-Ogden (He helped passed the SB 101 bill), Dave Mortensen, Art Valdez and Mae Varley

On October 13, 1987, President Mortensen signed a contract with the Public Service Commission to operate the Utah Relay Service in Utah (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, November 1987). The Utah Community Center for the Deaf had appointed Madelaine Perkins, a CODA and certified interpreter, to run as the Utah Relay System program director based at the Utah Community Center for the Deaf in Bountiful, Utah. The Utah Relay Service became the official title of the phone access relay system (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, November 1987).

The Utah Relay Service began operations on January 4, 1988, following a lengthy negotiation process and the establishment of a statewide phone relay service (UAD Bulletin, January 1993). The UAD operated the Utah Relay Service for ten years under a contract with the Public Service Commission (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, April 1999).

The Utah Relay Service began operations on January 4, 1988, following a lengthy negotiation process and the establishment of a statewide phone relay service (UAD Bulletin, January 1993). The UAD operated the Utah Relay Service for ten years under a contract with the Public Service Commission (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, April 1999).

Did You Know?

In July 1982, a survey of TeleCaption decoder owners revealed that 38% of them were currently subscribed to cable services. Interestingly, 85% of viewers who were not subscribed to cable services indicated they would subscribe if closed-captioned programming were available. Closed captioning had two advantages for cable franchises: it was a community service and helped build the audience. During that time, only ABC, NBC, and PBS provided closed captioning, which was only available for limited primetime hours (UAD Bulletin, July 2002). The Utah Association for the Deaf has come a long way since then!

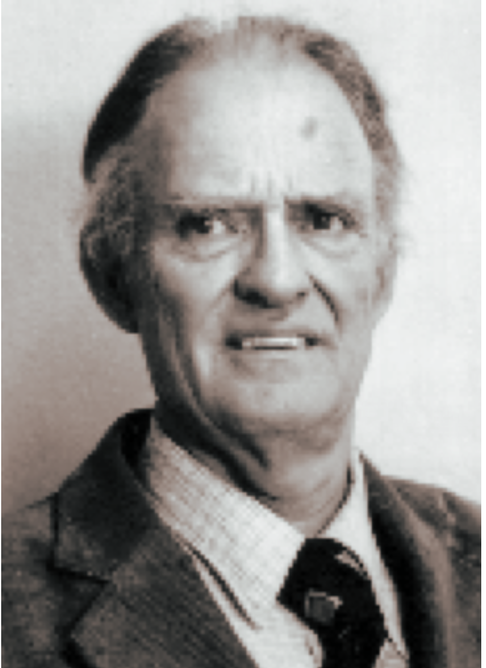

W. David Mortensen

Receives Consumer Award

Receives Consumer Award

On January 19, 1990, the Utah State Committee of Consumer Services presented W. David "Dave" Mortensen with a utility consumer achievement award at the State Capitol's Fifth Annual Utility Consumer Awards Celebration. The Committee honored Dave for his "commitment to strong consumer advocacy." In an article, the Committee for Consumer Services highlighted his efforts and contributions to ensuring equal access to phone services. An excerpt from the article reads as follows:

"Dave made sure the telephone is more accessible to the Deaf, the speech impaired, and the hard of hearing. In 1986, Dave began organizing support for Legislation making the telephone system more accessible for the hearing and speech impaired. With the help of Deaf and speech-impaired consumers...Dave led the formation of a broad coalition of supporters. The coalition drafted Legislation, found a sponsor, and successfully lobbied for the passage of a telecommunications access law. The law provides for establishing a relay service and distributing TTYs to low-income Deaf or speech-impaired consumers. Dave's leadership has made the telephone accessible to 15,000 disabled Utah consumers. Thank you, Dave, for making it happen" (UAD Bulletin, February 1990, p. 4).

"Dave made sure the telephone is more accessible to the Deaf, the speech impaired, and the hard of hearing. In 1986, Dave began organizing support for Legislation making the telephone system more accessible for the hearing and speech impaired. With the help of Deaf and speech-impaired consumers...Dave led the formation of a broad coalition of supporters. The coalition drafted Legislation, found a sponsor, and successfully lobbied for the passage of a telecommunications access law. The law provides for establishing a relay service and distributing TTYs to low-income Deaf or speech-impaired consumers. Dave's leadership has made the telephone accessible to 15,000 disabled Utah consumers. Thank you, Dave, for making it happen" (UAD Bulletin, February 1990, p. 4).

It’s a Matter of Fairness

Since the Utah Relay Service was established, Deaf relay users have had to wait patiently until an operator was available to make the call, and they have been frustrated for not being able to get through because the lines were always busy. Dr. Robert G. Sanderson stated in 1991 in the UAD Bulletin that the relay system, which allowed Deaf and hearing individuals to converse by telephone/TTY, was designed to serve everyone equally. That means a casual caller, a business call, a social chat, a life-threatening emergency, a local call, and a long-distance call.

It was brought to Dr. Sanderson's attention that some selfish relay users sought to monopolize restricted lines for their personal benefit, i.e., phone once, secure an operator, and demand that the operator make call after call, one after another, even if it took all day. He requested that the Utah Relay System for the Deaf limit calls "one at a"time"—finish one call and hang up before dialing again for the next. This would allow others to make their calls without waiting forever for an open line. With a limited number of telephone lines, it was easy for a salesperson, a businessperson, or several of them to totally clog the system, denying access to hundreds of people, let alone emergencies. Dr. Sanderson said, "It boiled down to a matter of fairness to all" (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, January 1991).

It was brought to Dr. Sanderson's attention that some selfish relay users sought to monopolize restricted lines for their personal benefit, i.e., phone once, secure an operator, and demand that the operator make call after call, one after another, even if it took all day. He requested that the Utah Relay System for the Deaf limit calls "one at a"time"—finish one call and hang up before dialing again for the next. This would allow others to make their calls without waiting forever for an open line. With a limited number of telephone lines, it was easy for a salesperson, a businessperson, or several of them to totally clog the system, denying access to hundreds of people, let alone emergencies. Dr. Sanderson said, "It boiled down to a matter of fairness to all" (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, January 1991).

The Utah Relay Service

Celebrates Five-Year Anniversary

Celebrates Five-Year Anniversary

On January 4, 1988, the Utah Relay Service (URS) began its operations without any grand ceremony. However, when the Utah Association for the Deaf reflected on the service in January 1993, they recognized that Utah was a pioneer in providing 24/7 relay services to Deaf callers, becoming the sixth state to do so. This information was sourced from the UAD Bulletin's January 1993 issue, which is as follows:

"In December 1987, Dr. Judy Ann Buffmire, Executive Director of the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, and Dave Mortensen, president of UAD, started working on the relay room in the former UCCD [Utah Community Center for the Deaf] in Bountiful and installed equipment.

In January [1988], there were 3,404 calls, and 5,269 in February. The Utah Relay Service handled approximately 175 calls every day. The Utahns were fast learning telephone etiquette.

By April, there were problems with equipment intercepting TTY calls. On URS computers, numbers became letters.

People complained about not getting through as the lines were always busy.

The Deaf callers were taught how to use credit cards to make long-distance calls

"In December 1987, Dr. Judy Ann Buffmire, Executive Director of the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, and Dave Mortensen, president of UAD, started working on the relay room in the former UCCD [Utah Community Center for the Deaf] in Bountiful and installed equipment.

In January [1988], there were 3,404 calls, and 5,269 in February. The Utah Relay Service handled approximately 175 calls every day. The Utahns were fast learning telephone etiquette.

By April, there were problems with equipment intercepting TTY calls. On URS computers, numbers became letters.

People complained about not getting through as the lines were always busy.

The Deaf callers were taught how to use credit cards to make long-distance calls

After May 13 [1988], the Utah Relay Service would take only one call per person to serve more callers and limit the calls to fifteen minutes. However, the UAD found that it did not receive enough money from the $.03 charge on all telephone lines to hire more operators.

By July, the UAD decided to return to the legislature and ask for a 10-cent cap on the Deaf tax on phone lines. The URS had to keep up with the fast-growing use of the relay services and cut down on the "all lines are busy; please hold" answer.

After six months in 1988, the Utah Relay Service handled 6800 calls. Within ten months, the relay had grown to 8,000 calls per month. The Utah Legislature approved the funding increase from three cents to a ten-cent cap by March 1989. Finally, the widely disliked message "Utah Relay. All lines are busy; please hold." has become a thing of the past. After five years, URS had come a long way" (UAD Bulletin, January 1993).

By 1993, a 7-cent surcharge on all Utah telephone bills had funded the Utah Relay Service. In the first quarter of 1992, the URS had eleven lines and received 20,000 more calls than in 1991. The URS was possibly the only agency run by a Deaf group, while private telephone companies ran most other state relays (UAD Bulletin, January 1993). The Utah Relay Service was in operation from 1987 to 1999.

By July, the UAD decided to return to the legislature and ask for a 10-cent cap on the Deaf tax on phone lines. The URS had to keep up with the fast-growing use of the relay services and cut down on the "all lines are busy; please hold" answer.

After six months in 1988, the Utah Relay Service handled 6800 calls. Within ten months, the relay had grown to 8,000 calls per month. The Utah Legislature approved the funding increase from three cents to a ten-cent cap by March 1989. Finally, the widely disliked message "Utah Relay. All lines are busy; please hold." has become a thing of the past. After five years, URS had come a long way" (UAD Bulletin, January 1993).

By 1993, a 7-cent surcharge on all Utah telephone bills had funded the Utah Relay Service. In the first quarter of 1992, the URS had eleven lines and received 20,000 more calls than in 1991. The URS was possibly the only agency run by a Deaf group, while private telephone companies ran most other state relays (UAD Bulletin, January 1993). The Utah Relay Service was in operation from 1987 to 1999.

TTYs Springing Up

Here and There in Utah

Here and There in Utah

Starting in 1992, TTYs became increasingly popular in Utah, as reported by the Utah Association for the Deaf's Bulletin. This was mainly due to the Americans with Disabilities Act that was passed in 1990, which encouraged many public places to offer various communication aids to people with hearing loss or speech limitations. The TTY pay phone, located at Murray's Fashion Place Mall, was most likely the first business TTY in Utah. Dave Mortensen discovered it and found it easy to use. To use the TTY, one needs to insert a quarter into a regular pay phone and dial the TTY number. A drawer slides out, and the caller connects the hook phone receiver to the TTY device and begins talking (UAD Bulletin, April 1992).

The Enactment

of the House Bill 217

of the House Bill 217

Utah passed House Bill 217 during its legislative session in 1994. As per this bill, the phone premium threshold was raised to 25 cents to fund and improve the Utah Relay System (Mortensen-Nelson, UAD Bulletin, March 1994, p. 2; UAD Bulletin, March 1994, p. 2-3).

Deaf Citizen’s Day a Big Success

The "Deaf Citizens' Day on the Hill" event was organized in February 1994, and it turned out to be a huge success. The State Office building auditorium was filled with around 200 people, including students from American Sign Language and Interpreters in Training classes, students and teachers from the Utah School for the Deaf, and many others from the Deaf community. Governor Mike Leavitt also attended the event and waved his hand while shaking hands with as many people as possible. He addressed the Utah Deaf community and signed the proclamation regarding Utah Relay Services after reading it. As he walked away, Governor Leavitt waved and smiled, and the audience applauded by waving their hands. The president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, Dave Mortensen, was moved by the Deaf community's spirit during the event (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, February 1994).

The Growth of the

Utah Relay Service

Utah Relay Service

In 1996, there were only two state associations for the Deaf running a relay system, and the Utah Association for the Deaf was one of them. They were pleased to report that since 1998, they had experienced tremendous growth with very few problems. For instance, in 1988, they had 89,626 calls; since then, they had received around 2,118,155 calls. Despite the high volume of calls, there had been surprisingly few complaints. Madelaine Perkins, UAD's program director, attributed a significant portion of this success to her skills and dedication (Sanderson, UAD Bulletin, January 1996).

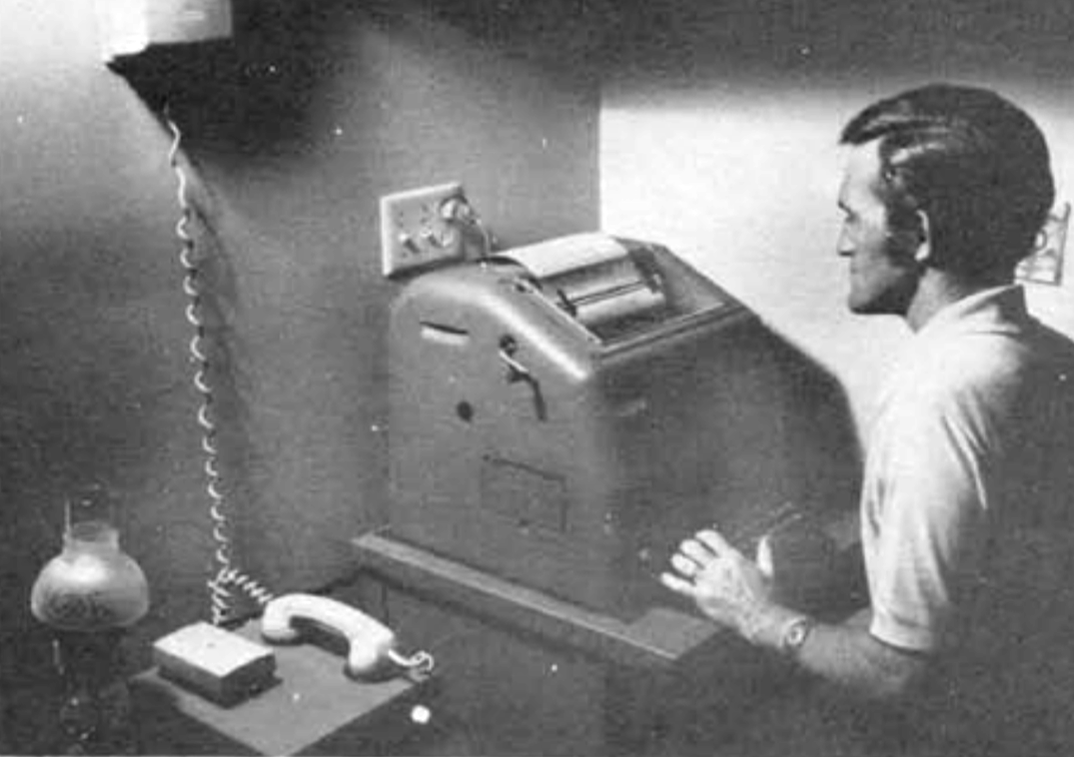

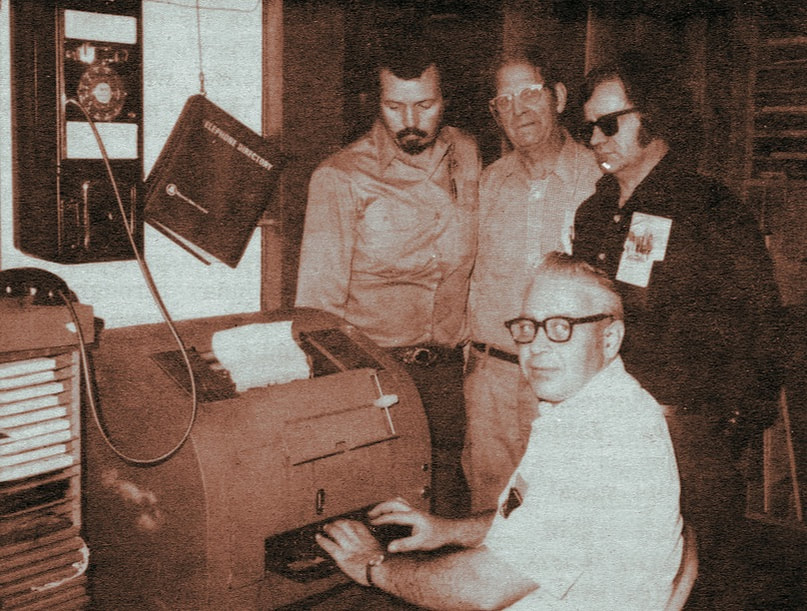

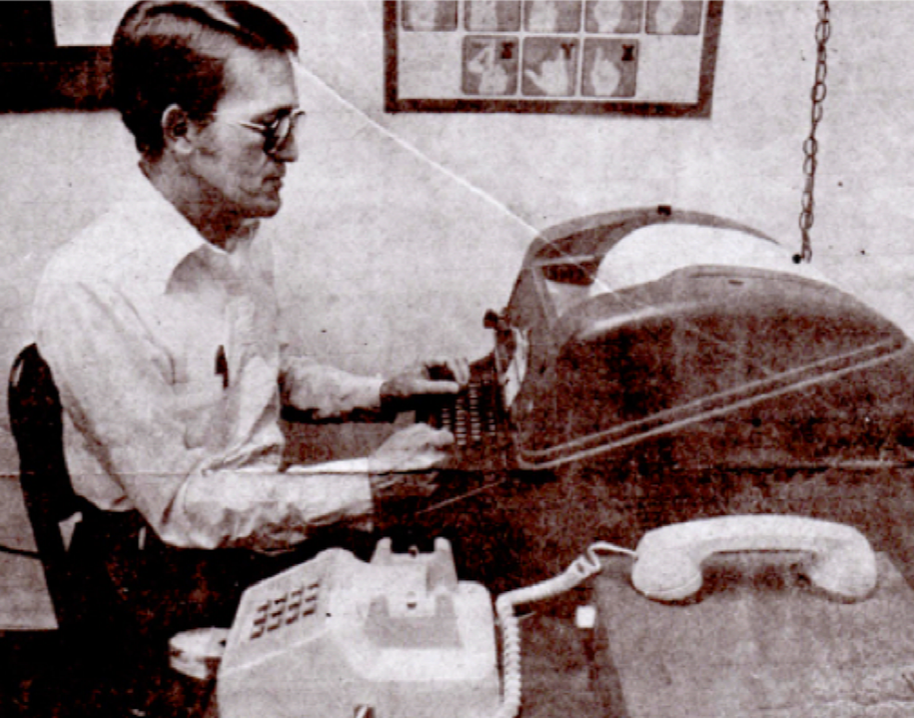

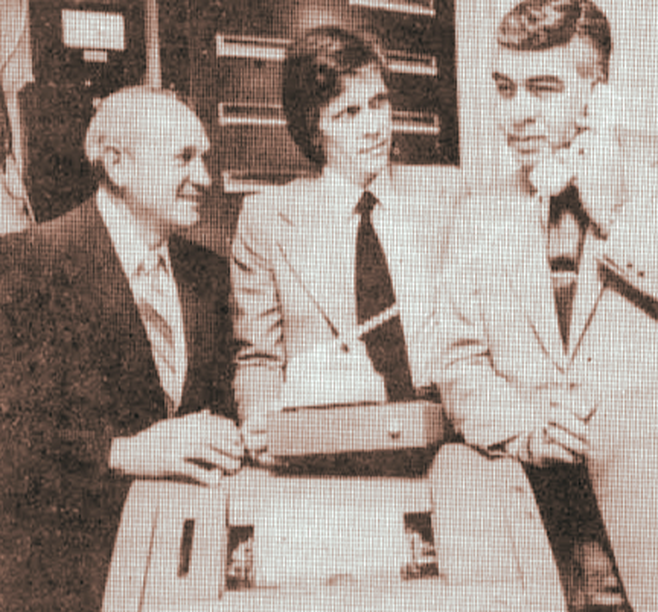

A new TTY service has been initiated by the Salt Lake City Police Department. Deaf persons can call the department when they need help. In the picture above are left to right: Deaf advocate, Lloyd H. Perkins, Salt Lake City Commissioner, Glen N. Greener, and Chief of Police Dewey J. Fillis. Perkins donated the teletype unit and the city bought the converter. Chief Fillies said the price have been train to operate the system. Calls have nee relayed, when necessary, to doctors, paramedics, and other persons whom Deaf families needed in a hurry. UAD Bulletin, April 1975

Utah Relay Service Executive Director Retires

Madelaine Perkins retired as Executive Director of the Utah Relay Service for the Deaf on September 30, 1996. The Utah Association for the Deaf hired her in 1988 to establish a relay system, and for the past eight years, she has diligently overseen the URS activities for the UAD. Madelaine brought a wealth of knowledge and experience to the role, having been an interpreter, married to a Deaf person, and working as an executive secretary for a businesswoman. Despite facing numerous challenges, she did an exceptional job, and the Deaf community in Utah greatly benefited. Thanks to her efforts, Utah became one of only one or two independent relay systems coveted by big companies like AT&T, MCI, and Sprint. Deaf people, on the other hand, demonstrated that they were capable of running it with modest improvement and great support from the Utah Public Service Commission (UAD Bulletin, September 1996).

The Deaf Mortensen Family Meets

Utah Governor Michael Okerlund Leavitt

Utah Governor Michael Okerlund Leavitt

In 1996, the Deaf Mortensen family of Dave, Shanna, and their daughter Kristi visited Utah Governor Michael Okerlund Leavitt on behalf of the Utah Deaf community and requested that he support the Utah Relay Service.

Sprint Takes Over

the Utah Relay Service

the Utah Relay Service

The Utah Public Service Commission (PSC) has been providing the Utah Relay Service since 1988, as authorized by the State of Utah, under a contract with the Utah Association for the Deaf (UAD). The contract with UAD was set to expire in 1999, and following a competitive bidding process approved by the State of Utah, the PSC selected Sprint and awarded the contract (UAD Bulletin, February 2000).

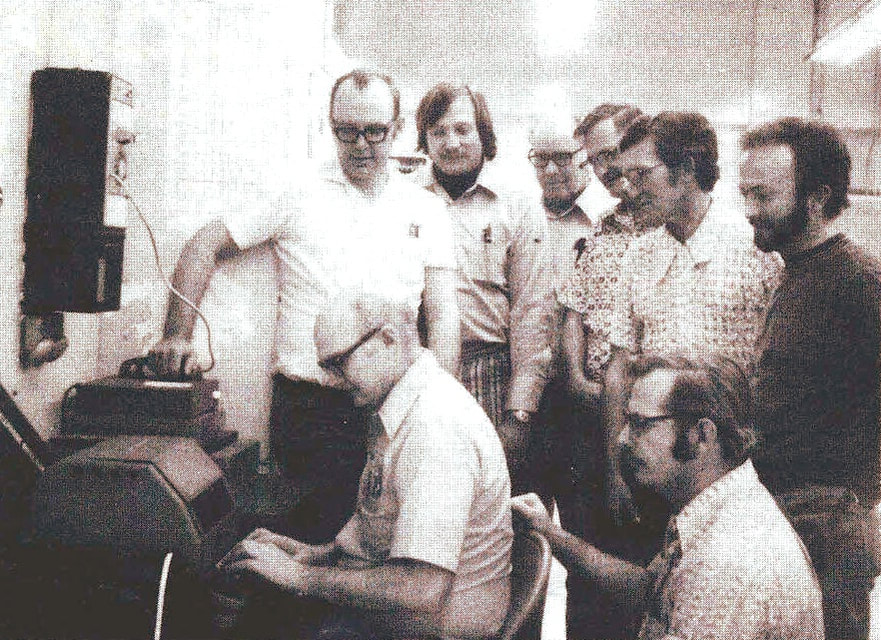

After Sprint took over the Utah Relay, it was voted to use

the money to establish an interpreter training program at Salt Lake Community College. L-R: Robert Sanderson, Jeff Pollock, Dave Mortensen, Shanna Mortensen, Craig Radford, Robert Kerr, JR Goff, Rep. Spendlove of the Utah House of Representative, who gets it passed with Gov. Jonathan Huntsman’s, Jr. sitting

In a bid with the Public Service Commission, Sprint won the Utah Relay Service. However, the Deaf community was outraged by Sprint's decision. Dr. Robert G. Sanderson led the UAD management team, which studied the situation for more than two years and concluded that Hamilton, employing Utah workers, would provide better service to Utah Deaf and Hard of Hearing, as well as speech-impaired people. Sprint had placed all calls at one of its out-of-state, difficult-to-reach call centers, which was not ideal for the community. Despite having no say in the Utah Public Service Commission's bidding decision, Dr. Sanderson preferred Hamilton to Sprint. Regrettably, the Utah Relay Service shut down in 2000. The TTY became obsolete when Sorenson Communication, Inc. entered the picture in 2003.

The Birth of Video

Relay Service Industry

Relay Service Industry

In 2003, Sorenson Communications, Inc., a company based in Salt Lake City, Utah, revolutionized communication for the Deaf community by introducing the first videophone. This groundbreaking innovation was developed by Jonathan Hodson, a native of Utah who is Deaf. Today, Sorenson Communications, Inc. continues to offer a video relay system that is 'functionally equivalent,' making communication more accessible for users, a true testament to the enduring impact of his initial innovation. In a November 7, 2009 e-mail interview with Jonathan Hodson, he shared how Sorenson Communications, Inc. started the video relay service. Thanks to his leadership, Deaf people now have access to this service, which benefits all of us. Here's his story.

In 1981, while studying at Los Angeles Pierce College, Jonathan Hodson, who was a former Director of Business Development at Sorenson Communication, Inc. and a Utah native, explored the possibility of transmitting video data over an analog line (plain old telephone system, or POTS) via a 28.8-kilobit modem. He consulted a computer professor with a classmate to investigate the feasibility of such a transmission. The professor thought about it, took a deep breath, and drew frequency diagrams on the whiteboard. After some reasoning, he concluded that transmitting video data through that technology was impossible. Nonetheless, Jonathan was determined to find a method to implement his concept, so he contacted a friend who worked as an electronic engineer for IBM in San Jose, California. He discussed the details of his idea with him, but his friend could not come up with a way, even after several days.

In 1981, while studying at Los Angeles Pierce College, Jonathan Hodson, who was a former Director of Business Development at Sorenson Communication, Inc. and a Utah native, explored the possibility of transmitting video data over an analog line (plain old telephone system, or POTS) via a 28.8-kilobit modem. He consulted a computer professor with a classmate to investigate the feasibility of such a transmission. The professor thought about it, took a deep breath, and drew frequency diagrams on the whiteboard. After some reasoning, he concluded that transmitting video data through that technology was impossible. Nonetheless, Jonathan was determined to find a method to implement his concept, so he contacted a friend who worked as an electronic engineer for IBM in San Jose, California. He discussed the details of his idea with him, but his friend could not come up with a way, even after several days.

In 1996, Jonathan received a call from his brother-in-law, James Lee Sorenson, Jr., of Sorenson Vision, Inc., informing him that his father, James LeVoy Sorenson, Sr., a Utah billionaire, and his executives wanted to demonstrate the video-conferencing software they had developed. Initially, Jonathan thought the video-conferencing equipment would likely display a choppy picture with missing frames, but he decided to give it a chance and see their latest technology. Jonathan and his interpreter traveled to California to meet with them and view their video software. To their amazement, the software proved to be highly capable of projecting the smooth and complex movements of a Deaf person utilizing American Sign Language.

In 1994, during a Thanksgiving dinner at the house of Jonathan's sister Elizabeth and her then-husband, James Lee Sorenson, James mentioned that his company was collaborating with Utah State University on video compression technology. He intended to buy the technology for his company. At the time, Jonathan had no idea what compression was. In the fall of 1996, Sorenson Vision hired him as director of business development. His responsibilities included marketing the company's video software to the Deaf community. Sorenson Vision developed VisionLink as its first product. It was created with the Deaf community in mind. Jonathan thought marketing this fantastic product would be simple. However, he was surprised to discover that the Deaf community was unprepared to embrace this significant shift in their mode of communication. They had grown accustomed to using a TTY for communication. They were concerned about losing their ability to write well in English. Women were particularly concerned about the possibility of appearing on video with their hair undone or in other unflattering settings.

Despite facing an initial setback, Jonathan remained committed to promoting the video software. He introduced the technology to various organizations for the deaf, universities with deaf programs, and influential individuals. His unshakable belief in the technology's potential and insistence that the future was available right now rather than in the distant future motivated others to see its possibilities. In 1998, Jonathan suggested using video relay interpreting technology to provide video relay interpreting to Sorenson Vision, but they ignored his idea. Meanwhile, Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD) expressed a strong interest in the video relay concept. They began pursuing it and eventually accepted it as a component of the telecommunication relay service (TRS), which the Federal Communications Commission finances.

The development of Sorenson EnVision, the second-generation video conferencing system after VisionLink, began in 1999. It served both the Deaf and hearing sectors and became an instant hit. Around the same time, the FCC approved video relay interpreting as a component of TRS, which later became a video relay service, or VRS. CSD and Sprint partnered up to provide VRS. They chose to use the free Microsoft NetMeeting software instead of Sorenson VisionLink. Ed Bosson, who was widely considered the father of video relay, had been trying to provide low-cost VRS to Deaf individuals in Texas. They collaborated with him for months, and in September 2000, they launched the first home-based video conferencing system. Texas became the first state in the United States to include EnVision on the state voucher list for services to Texas Deaf people.

Despite facing an initial setback, Jonathan remained committed to promoting the video software. He introduced the technology to various organizations for the deaf, universities with deaf programs, and influential individuals. His unshakable belief in the technology's potential and insistence that the future was available right now rather than in the distant future motivated others to see its possibilities. In 1998, Jonathan suggested using video relay interpreting technology to provide video relay interpreting to Sorenson Vision, but they ignored his idea. Meanwhile, Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD) expressed a strong interest in the video relay concept. They began pursuing it and eventually accepted it as a component of the telecommunication relay service (TRS), which the Federal Communications Commission finances.

The development of Sorenson EnVision, the second-generation video conferencing system after VisionLink, began in 1999. It served both the Deaf and hearing sectors and became an instant hit. Around the same time, the FCC approved video relay interpreting as a component of TRS, which later became a video relay service, or VRS. CSD and Sprint partnered up to provide VRS. They chose to use the free Microsoft NetMeeting software instead of Sorenson VisionLink. Ed Bosson, who was widely considered the father of video relay, had been trying to provide low-cost VRS to Deaf individuals in Texas. They collaborated with him for months, and in September 2000, they launched the first home-based video conferencing system. Texas became the first state in the United States to include EnVision on the state voucher list for services to Texas Deaf people.

The Establishment of the

Sorenson Communications, Inc.

Sorenson Communications, Inc.

At the time, several telephone companies, including MCI, AT&T, Hamilton, CAC, and others, who received certification for Telecommunications Relay Services (TRS) from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), began collaborating with interpreting agencies to provide Video Relay Services (VRS). Jonathan presented the EnVision product to Sprint, AT&T, MCI, and other phone carriers, but they were uninterested. Instead, they preferred to use the free Microsoft NetMeeting software. In 2001 and 2002, Jonathan pitched the video relay concept to Sorenson Vision (later Sorenson Technology, which merged with Sorenson Media). Despite their potential earnings of $9 per minute, they hesitated to adopt the idea.

In July 2002, Jonathan and his associates set up a basic 10x10 booth to showcase the EnVision product at Gallaudet University's Deaf Way II event. Communication Services for the Deaf approached him during the event to ask if they could use EnVision for their large floor exhibit, which featured multiple stations and a giant screen that displayed video conferencing links. They had previously encountered issues with Microsoft NetMeeting due to bandwidth limitations, resulting in poor video quality. EnVision's video-compressing technology finally provided a clear motion, leading to the successful completion of the task. Thousands of Deaf attendees watched the video communication on the giant screen and were impressed with the technology. As a result, many of them visited Jonathan's booth to purchase EnVision. Following the event, Jonathan briefed Sorenson executives about the substantial revenue from Video Relay Service (VRS) that Communication Services for the Deaf generated over the seven-day event. He noted that the recent increase in the FCC's reimbursement rate to $14 per minute had significantly contributed to the revenue. The per-minute pay structure had opened their eyes to the VRS market's potential.

In July 2002, Jonathan and his associates set up a basic 10x10 booth to showcase the EnVision product at Gallaudet University's Deaf Way II event. Communication Services for the Deaf approached him during the event to ask if they could use EnVision for their large floor exhibit, which featured multiple stations and a giant screen that displayed video conferencing links. They had previously encountered issues with Microsoft NetMeeting due to bandwidth limitations, resulting in poor video quality. EnVision's video-compressing technology finally provided a clear motion, leading to the successful completion of the task. Thousands of Deaf attendees watched the video communication on the giant screen and were impressed with the technology. As a result, many of them visited Jonathan's booth to purchase EnVision. Following the event, Jonathan briefed Sorenson executives about the substantial revenue from Video Relay Service (VRS) that Communication Services for the Deaf generated over the seven-day event. He noted that the recent increase in the FCC's reimbursement rate to $14 per minute had significantly contributed to the revenue. The per-minute pay structure had opened their eyes to the VRS market's potential.

Jonathan proposed a collaborative operation between EnVision and VRS, as well as a partnership with a telephone company, which piqued James Lee Sorenson's interest. James asked Jonathan to prove him wrong and find a telephone company that would be interested in partnering with him. James assigned Jonathan the task of gathering and synthesizing information, and after about two weeks, he and his team informed James that the plan was viable. James was impressed and wished that Sorenson had started VRS years ago.

Jonathan met with several companies, including Sprint, MCI, AT&T, Hamilton, and CAC, while developing the standalone Sorenson VP-100 videophoneHowever, these companies showed no interest in the new technology and conducted their meetings via Microsoft NetMeeting. AT&T then launched a Request Form Program to obtain bids from VRS vendors, and Sorenson Media decided to submit a proposal. AT&T chose an interpreting agency as its partner in 2002, as Sorenson Media needed to gain more interpreting experience.

On their own, Sorenson Media applied for a VRS (Video Relay Service) certificate with the FCC (Federal Communications Commission). Despite several attempts and negotiations, the FCC issued a certificate to Sorenson Media, making it the first small, non-telephone VRS provider. Some phone companies, however, objected to Sorenson Media's certification because it was primarily a technology company. Nevertheless, Sorenson Media embraced VRS in April 2003. Splitting its operations to focus solely on VRS led to the founding of Sorenson Communications, Inc. (SCI). As a result, SCI became the nation's largest and fastest-growing video relay service provider, with over 70,000 Deaf users (Jonathan Hodson, personal communication, November 7, 2009). Additionally, this company was the first VRS provider to develop a videophone for the Deaf community (The Endeavor, Winter 2017).

Jonathan met with several companies, including Sprint, MCI, AT&T, Hamilton, and CAC, while developing the standalone Sorenson VP-100 videophoneHowever, these companies showed no interest in the new technology and conducted their meetings via Microsoft NetMeeting. AT&T then launched a Request Form Program to obtain bids from VRS vendors, and Sorenson Media decided to submit a proposal. AT&T chose an interpreting agency as its partner in 2002, as Sorenson Media needed to gain more interpreting experience.

On their own, Sorenson Media applied for a VRS (Video Relay Service) certificate with the FCC (Federal Communications Commission). Despite several attempts and negotiations, the FCC issued a certificate to Sorenson Media, making it the first small, non-telephone VRS provider. Some phone companies, however, objected to Sorenson Media's certification because it was primarily a technology company. Nevertheless, Sorenson Media embraced VRS in April 2003. Splitting its operations to focus solely on VRS led to the founding of Sorenson Communications, Inc. (SCI). As a result, SCI became the nation's largest and fastest-growing video relay service provider, with over 70,000 Deaf users (Jonathan Hodson, personal communication, November 7, 2009). Additionally, this company was the first VRS provider to develop a videophone for the Deaf community (The Endeavor, Winter 2017).

Sorenson Launches

Video Relay Service

Video Relay Service

Jonathan played a crucial role in raising awareness about the availability of low-cost video compression technology to the Deaf community. He shared this information with Deaf organizations and state relay administrators, which led to them petitioning the FCC to include video relay service in the telecommunications relay service infrastructure. In 2003, Sorenson Communication, Inc. launched a free video relay service (VRS) for the 28 million Deaf and hard of hearing people in the United States, thanks to Jonathan's perseverance. This service enables Deaf and hard of hearing individuals to make video relay calls to their family, friends, and business associates using a trained American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter and a broadband Internet connection (UAD Bulletin, May 2003). As a result, users can now access a "functionally equivalent" video relay system.

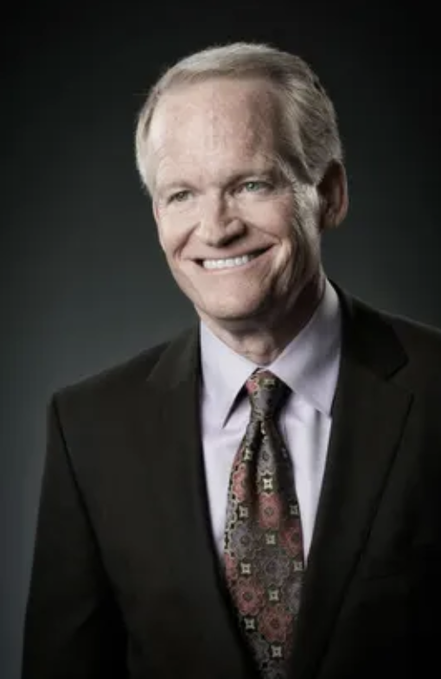

The video relay system, which provides "functionally equivalent" access, is now the most helpful form of relay service for Deaf and hard of hearing users. Ronald C. Burdett, a native of Utah who is also Deaf, has recently been appointed Vice President of Community Relations at Sorenson Communication, Inc.

In preparation for the 2007 Winter Dealympics in Utah, the Salt Lake City International Airport made history by becoming the first airport in the United States to offer free videophone booths for Deaf and hard of hearing travelers, provided by Sorenson Communications. Ronald Burdett, a Deaf individual and vice president of community relations for Sorenson Communication, Inc., expressed his excitement and said, "A lot of Deaf will see this from all around the world, and they'll be thrilled." Patrick Nola, the president and CEO of Sorensen Communications, also commented on this achievement, stating, "This is a historic first for the country. We hope this will serve as a model for other airports across the country" (Welling, The Deseret News, November 4, 2006).

The Development

of Closed Captions

of Closed Captions

Before 1930, the Deaf community could watch silent films or movies with subtitles. However, with the emergence of talking films in the 1930s, Deaf individuals faced a disadvantage as films lacked captions for over three decades (Walker, 2006). During this period, movies excluded Deaf people, as noted by Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a respected leader in the Deaf community (Sanderson, 2004). Although Dr. Malcolm J. Norwood, who was himself deaf, made efforts to promote captioning and is considered the "Father of Closed Captioning," it was only on June 30, 1960, that Captioned Films for the Deaf became available. Dr. Norwood, a director for the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, convinced higher-ups of the importance of providing Deaf individuals with an education through captioned films (Sanderson, 2004).

After receiving approval, Mac began developing a nationwide program of captioned films for Deaf and hard of hearing people. This sparked a great deal of interest in the Deaf community. As a result, thousands of Deaf individuals rented or purchased 16-mm projectors to use with the films from the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare's film library in Washington, D.C., which the department made available to them (Sanderson, 2004).

After receiving approval, Mac began developing a nationwide program of captioned films for Deaf and hard of hearing people. This sparked a great deal of interest in the Deaf community. As a result, thousands of Deaf individuals rented or purchased 16-mm projectors to use with the films from the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare's film library in Washington, D.C., which the department made available to them (Sanderson, 2004).

Established in July 1960, the United Utah Organizations of the Deaf collaborated with various local organizations, including the Utah Association of the Deaf, the Utah Athletic Club of the Deaf, the Salt Lake Frats, the Ogden Frats, the Salt Lake Valley Branch for the Deaf, the Ogden Branch for the Deaf, and other organizations within the Deaf community in Utah. Their primary objective was to coordinate dates for each group's activities to avoid overlapping meetings and events so everyone could participate. During a meeting on May 1, 2004, representatives from various organizations voted to dissolve the United Organizations for the Deaf (UAD Bulletin, June 2004). In the 1970s and 1980s, Dr. Norwood's perseverance paid off when the captioning industry as we know it today was born (Feldman, 2008). Closed-captioned TV series were popular at the time, and "this attracted Deaf people away from captioned film showings at Frat meetings" (Walker, 2006). Despite the gradual phaseout of subtitled film screenings, the Frat continued to meet.

On October 16, 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed the "Television Decoder Circuitry Act" into law. The law required television sets with 13 inches or more display sizes to have built-in closed captions by July 1, 1993 (UAD Bulletin, December 1990). Zenith was the first company to release TVs with closed captioning in late 1991, just in time for the holidays. They offered both portable and console models, with the closed captions large enough to read from a distance (Kinney, UAD Bulletin, April 1992). By 1993, two more television manufacturers, JVC and Toshiba, had released models with built-in closed caption decoders (UAD Bulletin, July 1993). This was a significant development for the Deaf and hard of hearing communities, who no longer needed to purchase a decoder to watch TV with closed captions. They could now enjoy TV with closed captions in a hotel room or at friends' and family members' homes, making it a dream come true for them.

On October 16, 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed the "Television Decoder Circuitry Act" into law. The law required television sets with 13 inches or more display sizes to have built-in closed captions by July 1, 1993 (UAD Bulletin, December 1990). Zenith was the first company to release TVs with closed captioning in late 1991, just in time for the holidays. They offered both portable and console models, with the closed captions large enough to read from a distance (Kinney, UAD Bulletin, April 1992). By 1993, two more television manufacturers, JVC and Toshiba, had released models with built-in closed caption decoders (UAD Bulletin, July 1993). This was a significant development for the Deaf and hard of hearing communities, who no longer needed to purchase a decoder to watch TV with closed captions. They could now enjoy TV with closed captions in a hotel room or at friends' and family members' homes, making it a dream come true for them.

Federal law requires captions to be included in television programs and wide-release films. This has made it possible for people who are deaf to enjoy captioned television shows and movies. The Popcorn Coalition and Utah-CAN have made efforts to include more captioned movies in Utah theaters. With the advancement of technology, there has been an increase in the number of American Sign Language (ASL)) films produced and directed by Deaf directors and producers. Lance Pickett of R.E.M. Films, Julio Diaz, Bobby Giles, and Jim Harper of Eye-Sign Media are local Utah film producers.

TV Stations

In 1993, the Utah Association for the Deaf persuaded two more local TV stations to provide captions for their news broadcasts. However, the UAD still had to put in more effort to ensure that the TV stations would provide "real-time" captioning mode, which would allow Deaf viewers to have the same access to the news as hearing viewers (Mortensen, UAD Bulletin, June 1995). By 1997, three local TV stations had implemented "real-time" captioning for their nightly news broadcasts: Channel 13 Fox, Channel 2 KUTV, and Channel 4 KTVX. The UAD expressed their appreciation to these TV stations for considering the needs of their Deaf viewers and providing them with equal access to information (UAD Bulletin, July 1997, p. 4).

Technological advancements have made a significant impact in the last 100 years, providing Deaf and hard of hearing people with access to the information that society takes for granted. The Utah Deaf community values technology because it allows them to communicate more effectively with both the Deaf and hearing worlds.

Technological advancements have made a significant impact in the last 100 years, providing Deaf and hard of hearing people with access to the information that society takes for granted. The Utah Deaf community values technology because it allows them to communicate more effectively with both the Deaf and hearing worlds.

Notes

Jonathan Hodson, personal communication, November 7, 2009.

Jonathan Hodson, personal communication, October 27, 2013.

Jonathan Hodson, personal communication, October 27, 2013.

References

“20 Years Ago...” UAD Bulletin, vol. 26.2 (July 2002): 5.

“Hooray for SB42.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 10 (March 1994): 2-3.

“Lobby Your Legislators!” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 9 (February 1987): 3.

“‘Joe,’ 62, hears his first sound by ‘plugging’ into a U. computer.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 2 (June 1975): 4.

“Happy 5th Birthday, Utah Relay Service!!” UAD Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 8 (January 1993): 1.

Kinney, Valerie. “New Zenith Owners Experience Problems.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 11 (April 1992): 3-4.

“More Built-in Televisions in Stores.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 18, no. 2 (July 1993): 11.

“Mortensen Receives Consumer Award.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 12, No. 22 (February 1990): 4.

Mortensen, David. “Deaf Citizen’s Day a Big Success.” UAD Bulletin, v. 17, no. 9 (February 1994): 1.

Mortensen, David. “UAD President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 19.1 (June 1995): 4.

Mortensen, David. “UAD President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 20.5 (October 1996): 4.

Nelson-Mortensen, Kristi. “Progress on Capitol Hill.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 10 (March 1994): 2.

Platt, Dennis. “President’s Corner.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 6, no. 1 (Fall 1969): 2.

Mortensen, W. David. “President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 3 (October 1975): 2.

Mortensen, W. David. “President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 11, no. 6 (November 1987): 2.

Mortensen, W. David. “President’s Message.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 11, no. 8 (January 1988): 2.

Sanderson, Robert G. “It’s a Matter of Fairness.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 14, no. 8 (January 1991): 4.

Sanderson, Robert G. “URS Needs Communication Assistants.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 19.8 (January 1996): 3.

“Speech and Hearing Impaired Telephone Surcharge.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 8 (December 1988): 4.

“Summary of Board Minutes.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 12 (May 1987): 2.

“Technology Has Changed Deaf Life: Is Your Child Benefitting?” The Endeavor (Winter 2017): 41.

“Telephone Access Bill Moves in Legislature.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 10 (March 1987): 2.

“Telephone Access and Relay Service Bill.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 8 (January 1987): 3.

“TDDs Springing Up Here and There in Utah.” UAD Bulletin, v. 15, no. 11 (April 1992): 2.

“UAD Convention Business Meeting June 13-14, 1997.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 21.2 (July 1997): 4.

“UAD Convention in Provo a First.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 11. No. 1 (July 1987): 2.

“URS Executive Director to Retire.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 20.4 (September 1996): 6.

“Utah Deaf Lead Nation in Ear Research.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 9, no. 3 (June 1974): 2.

Walker, Rodney, W. My Life Story, 2006.

Welling, Angie. “Airport Videophones a First in U.S.” The Deseret News, November 4, 2006.

“Hooray for SB42.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 10 (March 1994): 2-3.

“Lobby Your Legislators!” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 9 (February 1987): 3.

“‘Joe,’ 62, hears his first sound by ‘plugging’ into a U. computer.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 2 (June 1975): 4.

“Happy 5th Birthday, Utah Relay Service!!” UAD Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 8 (January 1993): 1.

Kinney, Valerie. “New Zenith Owners Experience Problems.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 15, no. 11 (April 1992): 3-4.

“More Built-in Televisions in Stores.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 18, no. 2 (July 1993): 11.

“Mortensen Receives Consumer Award.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 12, No. 22 (February 1990): 4.

Mortensen, David. “Deaf Citizen’s Day a Big Success.” UAD Bulletin, v. 17, no. 9 (February 1994): 1.

Mortensen, David. “UAD President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 19.1 (June 1995): 4.

Mortensen, David. “UAD President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 20.5 (October 1996): 4.

Nelson-Mortensen, Kristi. “Progress on Capitol Hill.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 10 (March 1994): 2.

Platt, Dennis. “President’s Corner.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 6, no. 1 (Fall 1969): 2.

Mortensen, W. David. “President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 3 (October 1975): 2.

Mortensen, W. David. “President’s Message.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 11, no. 6 (November 1987): 2.

Mortensen, W. David. “President’s Message.” The UAD Bulletin, vol. 11, no. 8 (January 1988): 2.

Sanderson, Robert G. “It’s a Matter of Fairness.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 14, no. 8 (January 1991): 4.

Sanderson, Robert G. “URS Needs Communication Assistants.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 19.8 (January 1996): 3.

“Speech and Hearing Impaired Telephone Surcharge.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 8 (December 1988): 4.

“Summary of Board Minutes.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 12 (May 1987): 2.

“Technology Has Changed Deaf Life: Is Your Child Benefitting?” The Endeavor (Winter 2017): 41.

“Telephone Access Bill Moves in Legislature.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 10 (March 1987): 2.

“Telephone Access and Relay Service Bill.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 10, no. 8 (January 1987): 3.

“TDDs Springing Up Here and There in Utah.” UAD Bulletin, v. 15, no. 11 (April 1992): 2.

“UAD Convention Business Meeting June 13-14, 1997.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 21.2 (July 1997): 4.

“UAD Convention in Provo a First.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 11. No. 1 (July 1987): 2.

“URS Executive Director to Retire.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 20.4 (September 1996): 6.

“Utah Deaf Lead Nation in Ear Research.” UAD Bulletin, vol. 9, no. 3 (June 1974): 2.

Walker, Rodney, W. My Life Story, 2006.

Welling, Angie. “Airport Videophones a First in U.S.” The Deseret News, November 4, 2006.