Sociology of the Utah School for the Deaf

in the Utah Deaf Community,

1890-1970

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2015

Updated in 2024

Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2015

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

We are deeply grateful to Elaine Roberts for her master's thesis, 'The Early History of the Utah School for the Deaf and Its Influence on the Development of a Cohesive Deaf Society in Utah, c. 1884–1905,' published in 1994. This work is a critical component of the history of the Utah School for the Deaf. This 'Sociology of the Utah School for the Deaf in the Utah Deaf Community' webpage has been instrumental in disseminating her invaluable discoveries. Thank you, Elaine Roberts, for your outstanding contribution!

Anne Leahy and Doug Stringham, esteemed scholars, have dedicated their careers to extensive research on the history of Deaf Latter-day Saints in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well as the early history of the Utah School for the Deaf. Their research collection, 'Far Away, In the West: The Emergence of Utah's Deaf Community, 1885–1910,' contains valuable information about our Utah Deaf Community's early history. I wanted to thank Anne and Doug for providing information on the early history of the Utah Deaf Community and for Doug's recommendation to name this title as seen above in the manuscript that transformed into this webpage. A heartfelt thank you for your contributions to this project!

This webpage also delves into the pivotal role of the Utah School for the Deaf, established in 1884, in shaping the Utah Deaf community. The USD has been instrumental in developing Deaf communities in Ogden and Salt Lake City, with its students often becoming future community leaders. Furthermore, the 1960s witnessed and experienced the profound impact of the oral and mainstreaming movements on our Utah Deaf community.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in reading the webpage titled 'Sociology of the Utah School for the Deaf in the Utah Deaf Community.' This webpage is very intriguing to me because it contains information about the early history of the Utah School for the Deaf and the formation of the Utah Deaf Community.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Anne Leahy and Doug Stringham, esteemed scholars, have dedicated their careers to extensive research on the history of Deaf Latter-day Saints in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well as the early history of the Utah School for the Deaf. Their research collection, 'Far Away, In the West: The Emergence of Utah's Deaf Community, 1885–1910,' contains valuable information about our Utah Deaf Community's early history. I wanted to thank Anne and Doug for providing information on the early history of the Utah Deaf Community and for Doug's recommendation to name this title as seen above in the manuscript that transformed into this webpage. A heartfelt thank you for your contributions to this project!

This webpage also delves into the pivotal role of the Utah School for the Deaf, established in 1884, in shaping the Utah Deaf community. The USD has been instrumental in developing Deaf communities in Ogden and Salt Lake City, with its students often becoming future community leaders. Furthermore, the 1960s witnessed and experienced the profound impact of the oral and mainstreaming movements on our Utah Deaf community.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in reading the webpage titled 'Sociology of the Utah School for the Deaf in the Utah Deaf Community.' This webpage is very intriguing to me because it contains information about the early history of the Utah School for the Deaf and the formation of the Utah Deaf Community.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Population of Deaf People

The population of Deaf people in Utah began to rise in 1849. According to the United States Census of 1860, 14 Deaf people were documented living in Salt Lake, Davis, Utah, and Iron counties. In 1900, Salt Lake, Davis, and Weber counties had 343 Deaf people. Ten years later, in 1910, the number of Deaf people declined. These counties had 236 Deaf people (Stringham & Leahy, 2013). There was no deaf school at the time, and there was no sense of community among Deaf people.

Deaf Utahns Educated or Tutored At Home

Deaf Utahns received their education or tutoring at home before the establishment of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1884. Long-time and well-known Deaf LDS history historians Anne Leahy and Doug Stringham report that during the Utah territory period, several Deaf children received homeschooling. The Utah Territory did not establish state educational agencies until 1877, and the Salt Lake City Board of Education did not exist until 1890. As a result, children in Utah, especially Deaf children, did not have access to a public school (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 7, 2011).

Between 1850 and 1880, parents of young Deaf children in Utah taught or tutored them at home. For example, Laron Pratt, the son of Apostle Orson Pratt, became deaf at the age of three and received his education at home. Sarah Eckersley was nine years old when her family emigrated to Utah. She had been deaf since she was eighteen months old. Her mother provided her with tutoring at home. The father of Mary Irene Foote, a Deaf woman who was born in Fort Union in 1855 and had two other Deaf sisters, educated her at home. Deaf adults who moved West may have attended schools for the Deaf in the East, like Henry C. White, who became principal and teacher of the Utah School for the Deaf. However, Deaf children had few options during the Utah Territory (Doug Stringham, personal communication, June 2, 2011).

Between 1850 and 1880, parents of young Deaf children in Utah taught or tutored them at home. For example, Laron Pratt, the son of Apostle Orson Pratt, became deaf at the age of three and received his education at home. Sarah Eckersley was nine years old when her family emigrated to Utah. She had been deaf since she was eighteen months old. Her mother provided her with tutoring at home. The father of Mary Irene Foote, a Deaf woman who was born in Fort Union in 1855 and had two other Deaf sisters, educated her at home. Deaf adults who moved West may have attended schools for the Deaf in the East, like Henry C. White, who became principal and teacher of the Utah School for the Deaf. However, Deaf children had few options during the Utah Territory (Doug Stringham, personal communication, June 2, 2011).

The Founding of the

Utah School for the Deaf

Utah School for the Deaf

The Utah School for the Deaf, a transformative institution that opened its doors in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1884, left an indelible mark on the lives of its students. The students at school not only received education but also fostered a profound sense of community during this period. As the Utah School for the Deaf evolved, it became a beacon of empowerment for its students. The majority of the student body comprised younger students, and their social dynamics shifted over time. The school's commitment to individual growth and independence was evident in the education and social skills training they provided. This training equipped the students to work together, find employment, and contribute meaningfully to society. Over time, the school's influence manifested itself in the evolving trends of Deaf marriages and vocational education training (Roberts, 1994).

The Utah Deaf community underwent transformative changes, empowered by the influence of the Utah School for the Deaf. The institution immediately set about preparing its students to become future leaders in Salt Lake City and Ogden, Utah. Moreover, it played a vital role in the establishment of social organizations for the deaf, both within and outside the state. This initiative provided students with a platform to enhance their leadership skills, enabling them to serve in a diverse array of social, educational, religious, and vocational groups (Roberts, 1994).

Prior to the establishment of the Utah School for the Deaf, individuals from congenital deaf hereditary families demonstrated remarkable resilience, having more experience in relating with other Deaf people than those from hearing families who later went deaf. Deaf siblings, parents, or other relatives were a common presence among those born deaf, fostering early connections with other Deaf individuals. In contrast, Deaf individuals from hearing families often felt more isolated. However, individuals with hearing backgrounds, such as John H. Clark (deaf at age 11), Elizabeth DeLong (deaf at age 5), Dr. Robert G. Sanderson (deaf at age 11), and Ned C. Wheeler (deaf at age 13), had an advantage. They could often speak before becoming deaf, and after learning sign language, they were able to communicate more effectively with both the Deaf and hearing communities than those who were born deaf and had difficulty learning to speak (Roberts, 1994).

In 1884, the Utah School for the Deaf was established, marking a significant milestone in the history of the Deaf community. Laron Pratt, a 37-year-old early Deaf leader, penned an essay to the editor of the Deseret News titled "Deaf Mutes: A Good Word in Behalf of the Unfortunates." This essay not only lauded the legislature's provision for Deaf children's education in the Utah Territory but also offered a unique perspective on the Deaf culture to a hearing audience (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011). Pratt's words resonate even today, as shown in the section below:

Prior to the establishment of the Utah School for the Deaf, individuals from congenital deaf hereditary families demonstrated remarkable resilience, having more experience in relating with other Deaf people than those from hearing families who later went deaf. Deaf siblings, parents, or other relatives were a common presence among those born deaf, fostering early connections with other Deaf individuals. In contrast, Deaf individuals from hearing families often felt more isolated. However, individuals with hearing backgrounds, such as John H. Clark (deaf at age 11), Elizabeth DeLong (deaf at age 5), Dr. Robert G. Sanderson (deaf at age 11), and Ned C. Wheeler (deaf at age 13), had an advantage. They could often speak before becoming deaf, and after learning sign language, they were able to communicate more effectively with both the Deaf and hearing communities than those who were born deaf and had difficulty learning to speak (Roberts, 1994).

In 1884, the Utah School for the Deaf was established, marking a significant milestone in the history of the Deaf community. Laron Pratt, a 37-year-old early Deaf leader, penned an essay to the editor of the Deseret News titled "Deaf Mutes: A Good Word in Behalf of the Unfortunates." This essay not only lauded the legislature's provision for Deaf children's education in the Utah Territory but also offered a unique perspective on the Deaf culture to a hearing audience (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011). Pratt's words resonate even today, as shown in the section below:

Deaf Mutes

A Good Word in Behalf of the Unfortunates

A Good Word in Behalf of the Unfortunates

Salt Lake City, April 16, 1884,

Editor Deseret News:

It is with a degree of pleasure that I note the fact that the Legislature at its last session, made provision for the instruction and education of the unfortunate deaf and dumb of the Territory, in its primary branches, a much needed and long desired measure which cannot but be of benefit to them. Though the number of deaf mutes in our Territory are but few, it is a step in the right direction to aid them to become useful and self supporting citizens, that they may not be a charge thrown up the community.

I have had a varied experience of some thirty years among these unfortunate beings, and I will say that though this faculty—the faculty of hearing—has been denied them, it is nevertheless true that most if not all are capable of being educated to a better standard of excellence in intellectual and moral culture.

Doubtless it would be interesting to many who do not understand these beings, to give a short sketch upon their mode of life and peculiar way of making themselves understood by those with whom they come in contact.

These are different grades of deafness and dumbness, which may be classified as follows: Those who have been born deaf and dumb are naturally the hardest to bring to an understanding of even the most simple, every-day things. As they grow up and their faculties begin to expand, a vast amount of patience and perseverance will be required of those under whose charge they are placed to bring them to a comprehension of the plainest affair, that is in their uneducated state. Their brain possesses almost the same functions as that of other beings, but are very dormant and of slow growth, aptness not being a characteristic, and rather conspicuous for its absence. They are capable of being educated, but only by object lessons—always have an object to point to when trying to make them comprehend, such as a picture, etc.—they can learn most of the words in common use. Then you bring them to understand the meaning of words by persistently pointing at the object of the sentence; they will thus known what is meant, but they will not know the sound of the word, even of dog, cat, etc. When educating this class many difficulties are to be met with. It would be requisite not only to have a large share of patience, but a good facial expression, with the power to denote love, hate, sorrow, humor, etc., thereon. Deaf and dumb are able to understand facial expression and are quick to comprehend every variety and expression of the human countenance; it amount to an intuition; nothing escapes their notice. Another thing required will be an expressive gesture, not only of the arms, fingers and shrug of the shoulders, but a peculiar movement of the whole body, in imitation and illustration of the subject you may be speaking of. They have a peculiar gesture to denote father, mother, sister, brother, uncle, aunt, etc., and for all the numerous objects that surround them, and whole sentences can be brought to their understanding by a simple gesture of the arm and face. When made familiar with words and objects they will be soon able to connect sentences and learn to put them in proper shape. I have met many deaf mates of eastern cities who considered themselves as having a good education, still in their conversation, which they usually write on small slates carried about in the pocket for that purpose—they seem to have the greatest difficulty in joining sentences together, and they have a rather peculiar way of doing it. Their general mode of conversing among themselves is not only be gestures, but also by means of the deaf and dumb alphabet—single or double; with one hand or with both. In many cases they can spell the object but do not know the meaning, which is explained to them by gesture.

Another class are those who have lost their hearing and in some cases their speech by disease, such as scarlet ever or some great sickness. Some are made totally deaf through the auditory nerve of the ear being destroyed, and some through catarrh and various other diseases. The mental and intellectual faculties of this class are of a superior organization to those of the other, and may, by cultivation, be brought up to a much higher plain. In fact this class may be educated to any degree on a par with the most intelligent being—their reasoning powers and mental capacity to grasp at ideas being the same—with the exception of hearing, and may be taught the sciences, different languages, etc., but is it doubtful whether they can ever attain to a higher degree of perfection or even excellence. They are naturally very sensitive as well as suspicious and generally get very much embarrassed when trying to pronounce a word that they cannot accentuate properly. This grade also have a peculiar way of their won in speaking, being generally through the medium of signs, but more particularly by the formation of words shaped by the mouth. It must be understood that those who are of this latter class, namely—deaf through disease—will be able to talk aloud in most instances like any other person, if brought up to it. And while being able to express themselves understandingly are still in a measure mute—the loss of the hearing more or less affecting the glands of the throat, which are in sympathy with the auditory nerve of the ear, rendering the voice thick, and it cannot be made to harmonize with the variety of sounds produced in speaking. Still they are able to get along in that way without the aid of many signs. If you will converse with an intelligent person who is thus afflicted by writing on a piece of paper or a slate, he will be found to be equal in ideas, expression and refinement to the most intelligent beings, but it is difficult for a person not well acquainted with their habit of understanding the lips by the forming of words thereon without sound to converse really intelligently by that mode. These unfortunates, according to the degree of education they may secure, and according to their intellectual capacity, are able to obtain a fair share of pleasure therefrom. They can more or less enjoy sounds. Even music has its charms. They may all hear different sounds, by this mode:

When a piano or instrument is being played they either put their feet against it or their hand on it, and thus what a mute may say he “heard” is conveyed by the jar of the sound on the nervous system, which vibrates along the member touching the instrument and communicates through the whole body, producing a most delightful music and sensation, and giving a tolerable idea of what music is. A piece of elastic rubber, with one end in the mouth between the teeth and stretched, and with one finger striking it in the middle makes it vibrate. This will give a tolerably fair idea of the sensation of sound.

I would by all means encourage the parents and guardians of these unfortunates to send them to the Deseret University, for by not doing so they know not the pleasure they are depriving them of—the capacity to enjoy what few pleasures fall to them. If they are too poor to send them to the institution, then, in the name of common humanity, let those who profess to be their friends show by their actions and not words—by subscribing means to that end—their appreciation of the condition of their unfortunate fellow-creatures.

Respectfully,

Laron Pratt (Deseret News, Apr. 1884)

Anne Leahy, a Deaf LDS history researcher, noted that Laron was a post-lingually deaf person with a high social status. He recognized his advantage and chose to use his dual citizenship in both the Deaf and hearing communities to act as an advocate and a bridge between the two worlds. While he was not a grassroots individual, he did not disregard those who were (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Editor Deseret News:

It is with a degree of pleasure that I note the fact that the Legislature at its last session, made provision for the instruction and education of the unfortunate deaf and dumb of the Territory, in its primary branches, a much needed and long desired measure which cannot but be of benefit to them. Though the number of deaf mutes in our Territory are but few, it is a step in the right direction to aid them to become useful and self supporting citizens, that they may not be a charge thrown up the community.

I have had a varied experience of some thirty years among these unfortunate beings, and I will say that though this faculty—the faculty of hearing—has been denied them, it is nevertheless true that most if not all are capable of being educated to a better standard of excellence in intellectual and moral culture.

Doubtless it would be interesting to many who do not understand these beings, to give a short sketch upon their mode of life and peculiar way of making themselves understood by those with whom they come in contact.

These are different grades of deafness and dumbness, which may be classified as follows: Those who have been born deaf and dumb are naturally the hardest to bring to an understanding of even the most simple, every-day things. As they grow up and their faculties begin to expand, a vast amount of patience and perseverance will be required of those under whose charge they are placed to bring them to a comprehension of the plainest affair, that is in their uneducated state. Their brain possesses almost the same functions as that of other beings, but are very dormant and of slow growth, aptness not being a characteristic, and rather conspicuous for its absence. They are capable of being educated, but only by object lessons—always have an object to point to when trying to make them comprehend, such as a picture, etc.—they can learn most of the words in common use. Then you bring them to understand the meaning of words by persistently pointing at the object of the sentence; they will thus known what is meant, but they will not know the sound of the word, even of dog, cat, etc. When educating this class many difficulties are to be met with. It would be requisite not only to have a large share of patience, but a good facial expression, with the power to denote love, hate, sorrow, humor, etc., thereon. Deaf and dumb are able to understand facial expression and are quick to comprehend every variety and expression of the human countenance; it amount to an intuition; nothing escapes their notice. Another thing required will be an expressive gesture, not only of the arms, fingers and shrug of the shoulders, but a peculiar movement of the whole body, in imitation and illustration of the subject you may be speaking of. They have a peculiar gesture to denote father, mother, sister, brother, uncle, aunt, etc., and for all the numerous objects that surround them, and whole sentences can be brought to their understanding by a simple gesture of the arm and face. When made familiar with words and objects they will be soon able to connect sentences and learn to put them in proper shape. I have met many deaf mates of eastern cities who considered themselves as having a good education, still in their conversation, which they usually write on small slates carried about in the pocket for that purpose—they seem to have the greatest difficulty in joining sentences together, and they have a rather peculiar way of doing it. Their general mode of conversing among themselves is not only be gestures, but also by means of the deaf and dumb alphabet—single or double; with one hand or with both. In many cases they can spell the object but do not know the meaning, which is explained to them by gesture.

Another class are those who have lost their hearing and in some cases their speech by disease, such as scarlet ever or some great sickness. Some are made totally deaf through the auditory nerve of the ear being destroyed, and some through catarrh and various other diseases. The mental and intellectual faculties of this class are of a superior organization to those of the other, and may, by cultivation, be brought up to a much higher plain. In fact this class may be educated to any degree on a par with the most intelligent being—their reasoning powers and mental capacity to grasp at ideas being the same—with the exception of hearing, and may be taught the sciences, different languages, etc., but is it doubtful whether they can ever attain to a higher degree of perfection or even excellence. They are naturally very sensitive as well as suspicious and generally get very much embarrassed when trying to pronounce a word that they cannot accentuate properly. This grade also have a peculiar way of their won in speaking, being generally through the medium of signs, but more particularly by the formation of words shaped by the mouth. It must be understood that those who are of this latter class, namely—deaf through disease—will be able to talk aloud in most instances like any other person, if brought up to it. And while being able to express themselves understandingly are still in a measure mute—the loss of the hearing more or less affecting the glands of the throat, which are in sympathy with the auditory nerve of the ear, rendering the voice thick, and it cannot be made to harmonize with the variety of sounds produced in speaking. Still they are able to get along in that way without the aid of many signs. If you will converse with an intelligent person who is thus afflicted by writing on a piece of paper or a slate, he will be found to be equal in ideas, expression and refinement to the most intelligent beings, but it is difficult for a person not well acquainted with their habit of understanding the lips by the forming of words thereon without sound to converse really intelligently by that mode. These unfortunates, according to the degree of education they may secure, and according to their intellectual capacity, are able to obtain a fair share of pleasure therefrom. They can more or less enjoy sounds. Even music has its charms. They may all hear different sounds, by this mode:

When a piano or instrument is being played they either put their feet against it or their hand on it, and thus what a mute may say he “heard” is conveyed by the jar of the sound on the nervous system, which vibrates along the member touching the instrument and communicates through the whole body, producing a most delightful music and sensation, and giving a tolerable idea of what music is. A piece of elastic rubber, with one end in the mouth between the teeth and stretched, and with one finger striking it in the middle makes it vibrate. This will give a tolerably fair idea of the sensation of sound.

I would by all means encourage the parents and guardians of these unfortunates to send them to the Deseret University, for by not doing so they know not the pleasure they are depriving them of—the capacity to enjoy what few pleasures fall to them. If they are too poor to send them to the institution, then, in the name of common humanity, let those who profess to be their friends show by their actions and not words—by subscribing means to that end—their appreciation of the condition of their unfortunate fellow-creatures.

Respectfully,

Laron Pratt (Deseret News, Apr. 1884)

Anne Leahy, a Deaf LDS history researcher, noted that Laron was a post-lingually deaf person with a high social status. He recognized his advantage and chose to use his dual citizenship in both the Deaf and hearing communities to act as an advocate and a bridge between the two worlds. While he was not a grassroots individual, he did not disregard those who were (Anne Leahy, personal communication, June 3, 2011).

Marriage of the Deaf Students

Jonathan Lambert, a Deaf resident on Martha's Vineyard, off the coast of Massachusetts, began the history of the Deaf in the United States in 1694. The secluded islanders' marriages passed down the deaf gene to his generation of descendants (Shapiro, 1994). In rural areas, especially in isolated regions of southern Utah, a pattern of hereditary congenital deafness was common due to inbreeding and intermarriage, similar to Martha's Vineyard. Furthermore, many Deaf families intermarried, perpetuating genetic deafness (Roberts, 1994).

In the West Virginia area, some families with deaf genes joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints early on. They eventually moved to southern Utah together. President Brigham Young of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent these families, along with other members of their families, to Utah. They continued intermarrying, with one or two Deaf relatives joining each generation. Several of these Deaf children had attended the Utah School for the Deaf since its inception. A couple of Deaf people got married. Most stayed home and helped their families (Roberts, 1994).

Polygamous intermarriage in Utah also contributed to the transmission of the deaf gene. While intermarriage was declining on Martha's Vineyard, it significantly decreased among Utah families once the students enrolled in the Utah School for the Deaf, providing them with the opportunity to interact with other Deaf individuals from across the state. As a result, deaf marriage patterns shifted due to socialization at school (Roberts, 1994).

With the expansion of the Utah School for the Deaf, the dynamics of deaf marriage shifted considerably. Before the establishment of the Utah School for the Deaf, Deaf students' marriage patterns differed from those of the hearing population. For example, they got married later than the general public. Most of them were unmarried, and few Deaf people lived alone. They either stayed home as maiden aunts and uncles to help with the family home or married someone from their local area. Interestingly, most Deaf educators and advocates at the time were opposed to Deaf-Deaf marriage. They frequently married hearing spouses to compensate for their deaf genes (Roberts, 1994).

In the West Virginia area, some families with deaf genes joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints early on. They eventually moved to southern Utah together. President Brigham Young of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent these families, along with other members of their families, to Utah. They continued intermarrying, with one or two Deaf relatives joining each generation. Several of these Deaf children had attended the Utah School for the Deaf since its inception. A couple of Deaf people got married. Most stayed home and helped their families (Roberts, 1994).

Polygamous intermarriage in Utah also contributed to the transmission of the deaf gene. While intermarriage was declining on Martha's Vineyard, it significantly decreased among Utah families once the students enrolled in the Utah School for the Deaf, providing them with the opportunity to interact with other Deaf individuals from across the state. As a result, deaf marriage patterns shifted due to socialization at school (Roberts, 1994).

With the expansion of the Utah School for the Deaf, the dynamics of deaf marriage shifted considerably. Before the establishment of the Utah School for the Deaf, Deaf students' marriage patterns differed from those of the hearing population. For example, they got married later than the general public. Most of them were unmarried, and few Deaf people lived alone. They either stayed home as maiden aunts and uncles to help with the family home or married someone from their local area. Interestingly, most Deaf educators and advocates at the time were opposed to Deaf-Deaf marriage. They frequently married hearing spouses to compensate for their deaf genes (Roberts, 1994).

According to Roberts (1994), over one-third of Deaf people never married before 1890. (p. 33). The following are three possible factors for early students' lack of marriage:

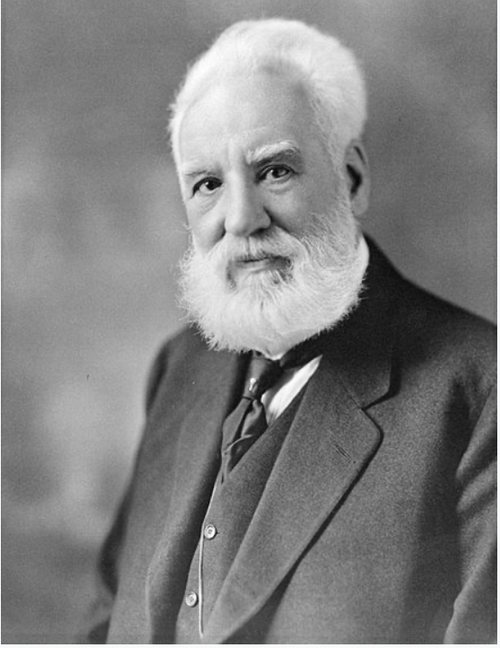

Alexander Graham Bell, also known as AGB, one of the most influential oral advocates and eugenicists of his time, was concerned about the rise of the Deaf community, which he saw as a result of sign language and state residential schools across the country. During his eugenics campaign, he aimed to ban Deaf people from socializing with one another, marrying one another, or reproducing with one another (Lane, 1984; Lane, 1999). He also proposed legislation barring Deaf people from marrying because he was worried that the deaf race would become more common (Behan, 1989e).

- The isolated nature of the rural areas where many of these students grew up made socialization difficult for the deaf,

- The environment had not changed to make it easier for deaf people to marry

- Often, family members accepted the prevailing opinion of many educators and advocates of the deaf that marriage should not be an option for deaf individuals (Roberts, 1994, p. 33–34).

Alexander Graham Bell, also known as AGB, one of the most influential oral advocates and eugenicists of his time, was concerned about the rise of the Deaf community, which he saw as a result of sign language and state residential schools across the country. During his eugenics campaign, he aimed to ban Deaf people from socializing with one another, marrying one another, or reproducing with one another (Lane, 1984; Lane, 1999). He also proposed legislation barring Deaf people from marrying because he was worried that the deaf race would become more common (Behan, 1989e).

In "Memoirs Upon the Formation of the Deaf Variety of the Human Race," which he submitted to the National Academy of Science in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1883, Alexander took a stand against the Deaf community and Deaf marriage. As a result of Deaf intermarriage, AGB claimed in this study that a "defective deaf race" was forming and getting stronger, resulting in more deaf births. His alarm was that the number of Deaf children enrolled in deaf residential schools was growing, spreading the "defective race." Furthermore, he believed a Deaf person would be more likely to marry another Deaf person at residential schools. As Deaf families intermarried generation after generation, a pure deaf breed of humans, or the Deaf Race, would emerge (Lane, 1984). AGB argued that prohibiting Deaf intermarriage would lead to a decrease in the number of Deaf births. He came up with two options:

AGB's book also pushed for removing Deaf teachers from the classroom and condemned the mixed-language educational system, including sign language and spoken instruction. He advocated "pure" oralism in the deaf education system. The law prohibiting Deaf intermarriage did not pass because he presented misleading scientific evidence about deaf intermarriages (Lane, 1984; Lane, 1999).

- Preventative method: Close all residential schools and place deaf kids in public schools with hearing kids and,

- Repressive method: Legally forbid congenitally deaf people from marrying each other when, in fact, statistics indicate that only 10% of deaf people have deaf parents, while 90% of Deaf people have hearing parents (Lane, 1984; Lane, Hoffmeister, & Bahan, 1996).

AGB's book also pushed for removing Deaf teachers from the classroom and condemned the mixed-language educational system, including sign language and spoken instruction. He advocated "pure" oralism in the deaf education system. The law prohibiting Deaf intermarriage did not pass because he presented misleading scientific evidence about deaf intermarriages (Lane, 1984; Lane, 1999).

In the past, there was a bill that aimed to ban marriages between Deaf people. Alexander Graham Bell supported this bill by presenting flawed scientific data. However, the bill did not become law, thanks to the efforts of Edward Allen Fay, a well-known teacher, publisher, and researcher in the field of Deaf education. Edward conducted a detailed study of Deaf marriages and deaf genetics, which led to his findings being published in 1893. Edward's research showed that most Deaf couples had hearing children, which contradicted AGB's belief that deafness was a hereditary trait that could be passed down through generations of Deaf families. As a result of Edward's research, AGB's misconceptions about Deaf marriage and heredity were corrected (Robert, 1994).

During the school's early years, there were several marriages between staff members and students, as well as between staff members' children. For example, Elizabeth DeLong, a Deaf teacher, married one of her students, Thomas Loran Savage. The residential school's environment allowed the students and staff to interact with each other, and it became a significant gathering place for Deaf people to socialize. As a result, there were several Deaf marriages during that time (Robert, 1994).

With the school's expansion, more Deaf people got married, and students at the Utah School for the Deaf had the opportunity to socialize with each other. Almost two-thirds of the students married within the first twenty years after their inception. Later on, the majority of students married other USD students. The school helped them learn new skills that enabled them to get married, live independently, and support their families (Roberts, 1994, p. 37).

With the school's expansion, more Deaf people got married, and students at the Utah School for the Deaf had the opportunity to socialize with each other. Almost two-thirds of the students married within the first twenty years after their inception. Later on, the majority of students married other USD students. The school helped them learn new skills that enabled them to get married, live independently, and support their families (Roberts, 1994, p. 37).

In addition, the Utah School for the Deaf allowed students to meet people from places other than where they lived. As a result, the school broke down the intermarriage patterns established in rural Utah. Here are some examples of how early school students can break down intermarriage patterns:

Since the school opened, social opportunities have changed the structure of the Utah Deaf community in a big way. Through the skills they learned at the Utah School for the Deaf, the students eventually contributed to their families, education, vocations, communities, and churches (Roberts, 1994).

- Joseph Olorenshaw came to Utah from England. His family settled in Salt Lake City, and he married Helmar Michelson, a fellow student from Largo, Idaho.

- John McMills was born in Summit County but married Pearl Ault, whose family lived in Cedar Fort, Utah.

- Ole Pettit grew up in Salt Lake City, but his wife, Jenine Jensen, was originally from Salina (Robert, 1994, p. 38).

Since the school opened, social opportunities have changed the structure of the Utah Deaf community in a big way. Through the skills they learned at the Utah School for the Deaf, the students eventually contributed to their families, education, vocations, communities, and churches (Roberts, 1994).

Students from the Same Families

According to Roberts (1994), during the first 25 years of its opening in 1884, many students at the Utah School for the Deaf came from the same families. After their stay at the Utah School for the Deaf, the nieces and cousins of the first couple married and returned to attend school together. Although their children did not attend school, many relatives from both families did (Roberts, 1994). Furthermore, many members of the same family attended the Utah School for the Deaf at the same time, such as Elizabeth DeLong and John H. Clark, who sent their relatives to school. Additionally, several sets of siblings, including the Beck, Bernard, and Thompson siblings, attended the school together (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Roberts, 1994).

During their time at the Utah School for the Deaf, the teachers encouraged the students to remain in touch with their families. While the majority of the families were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, parents of out-of-state students mainly were not. Utah parents preferred to enroll their children in a nearby school, whereas out-of-state parents moved their children to nearby institutions as soon as they became available. Regardless of the school's location, families frequently visited the campus and participated in school activities (Robert, 1994).

The social opportunities provided by the school enabled Deaf communities to grow in Ogden and Salt Lake City as the students moved out into the real world. As the students left school and integrated into the larger society, Deaf communities grew in Ogden and Salt Lake City due to the opportunities for social interaction provided by the school (Roberts, 1994).

The social opportunities provided by the school enabled Deaf communities to grow in Ogden and Salt Lake City as the students moved out into the real world. As the students left school and integrated into the larger society, Deaf communities grew in Ogden and Salt Lake City due to the opportunities for social interaction provided by the school (Roberts, 1994).

Social Development within the Utah Deaf Community

The Utah Deaf community had limited social opportunities until the opening of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1884. The school campus allowed students to socialize and connect with their peers. However, living on campus was challenging for some students who had to adjust to living away from home and sharing a dorm with others. To help students improve their social skills, staff members organized social activities. Students learned to collaborate, live and work independently, and develop their emotional and social skills through such activities. As a result, they were better equipped to contribute to society and live fulfilling lives (Roberts, 1994).

The school in Utah provided a range of activities for its students, their families, and the Deaf community. These social opportunities aimed to foster personal growth, encourage interaction with others, and improve social skills. By participating in these events, students were able to meet new people and develop into capable individuals, equipped to face the challenges of life in broader society (Roberts, 1994).

The First Deaf Student from Deaf Parents

Joseph Beck, Jr., was a former student at the Utah School for the Deaf. He enrolled his six-year-old son, Hyrum Hatch Beck, who was also deaf, at the school in the fall of 1906. The Utah Eagle reported on June 6, 1906, that Hyrum was the first Deaf student of Deaf parents to enroll at the Utah School for the Deaf. Joseph Beck, Jr. was the son of Joseph Beck, one of the co-founders of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1884.

Social Interests Among Boys and Girls

In 1921, the Utah School for the Deaf had 126 students. Primary Hall housed 42 students, while the Main Building housed 84 (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

During their time at school, the boys became interested in battle. Some of the school staff were veterans who had fought in wars, and their stories fascinated the boys. The veterans divided the young boys into groups and had them engage in fake wars against each other. Arthur W. Wenger, a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1913, frequently visited the school and encountered a student who would act "violently" when disturbed. Arthur referred to the boy as a "defeated general" who had either lost the war or was concerned about the safety of his troops when victory was uncertain (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

During their time at school, the boys became interested in battle. Some of the school staff were veterans who had fought in wars, and their stories fascinated the boys. The veterans divided the young boys into groups and had them engage in fake wars against each other. Arthur W. Wenger, a graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf in 1913, frequently visited the school and encountered a student who would act "violently" when disturbed. Arthur referred to the boy as a "defeated general" who had either lost the war or was concerned about the safety of his troops when victory was uncertain (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

During various Indian wars, the boys participated in battles along the Ogden River using trenches, machine guns, cudgels, swords, and helmets made of cushioned cooking utensils. These battles were so daring that they even trampled the dead. The boys kicked, laughed, and threw dirt, corks, and various missiles in the air. However, during one of these battles, the generals drafted the younger boys while playing baseball, negatively impacting the game. The older boys urged the generals to allow the drafted baseball players to return to the game. The big guys vowed to end the war if they denied the appeal. As a result, the armies disbanded, and the little boys showed their support for baseball by tossing down their rocks (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

The boys tended focus on more structured activities, while the girls enjoyed engaging in free-spirited activities like spinning around in circles. There were also gifted storytellers, such as "Peter Pan," who was always at the center of a joyful gathering, and "Princess," who could spin a good tale. One exceptionally skilled girl earned a nickname for her leadership in various activities. (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

The boys tended focus on more structured activities, while the girls enjoyed engaging in free-spirited activities like spinning around in circles. There were also gifted storytellers, such as "Peter Pan," who was always at the center of a joyful gathering, and "Princess," who could spin a good tale. One exceptionally skilled girl earned a nickname for her leadership in various activities. (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

Students of the Utah School for the Deaf, 1917-1918. 1st Top Row (L-R): Waldron Robinson, Arthur Hutcheson, Lee Hunter, George Roth, Marvin Stanly or possible Stanley, Nat Underwood, & Allen Fowler. 2nd Row (L-R): Albert Price, Lorn Alsof (maybe Joe Brandberg), Kenneth Burdett, Virgil Greenwood, & George Laramie. 3rd Bottom Row (L-R): Wayne Stewart & Oliver Woodard

Swimming Pool Enjoyment

The Utah School for the Deaf would fill up a swimming pool with fresh water every week and make it available to all groups at specific times. The swimmers were allowed to shout as loudly as they wanted, and the boys and girls were filled with excitement and joy. Arthur W. Wenger believed that this was a great way for them to release their emotions, which could help them manage their anger and avoid conflicts in the future (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

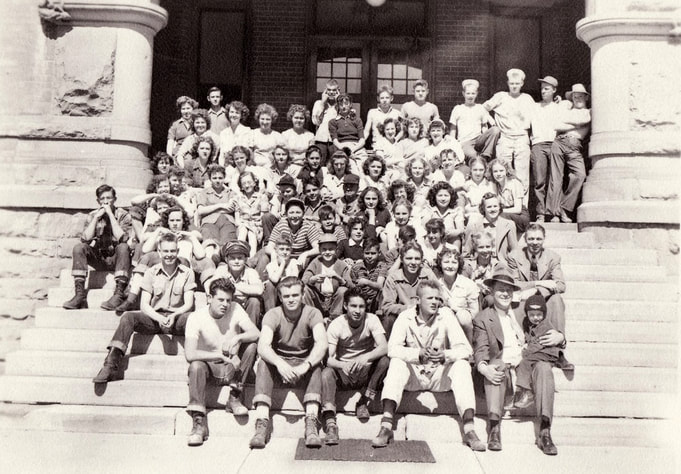

Students of Utah School for the Deaf, 1928-1930. Back L-R: Wayne Stewart, William Woodward, Alton Fisher, John (Jack) White, Joseph Burnett, possible Leon Edwards, Arvel Christensen, Virgil Greenwood, ____ Front L-R: J. Sherwood Messerly, Rodney Walker, Melvin Penman, Wesley Perry, Verl Throup, _____

Extracurricular Activities

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

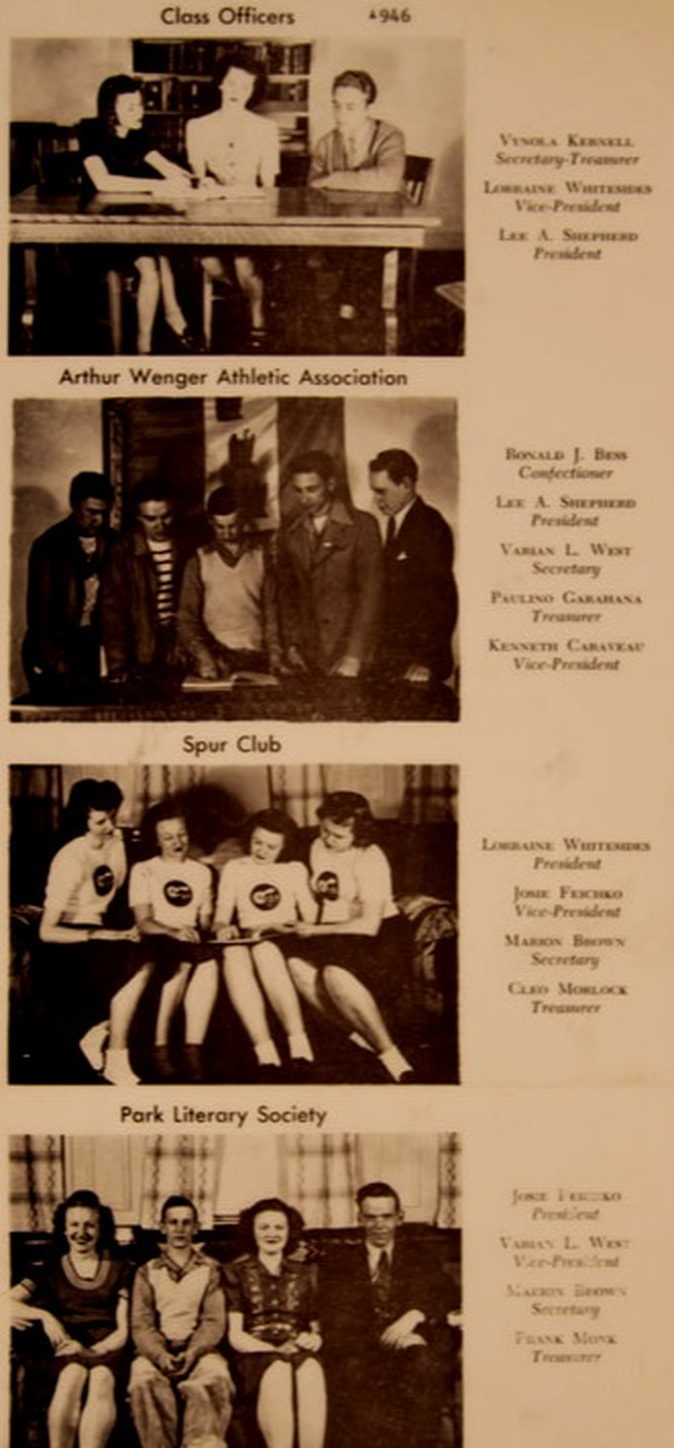

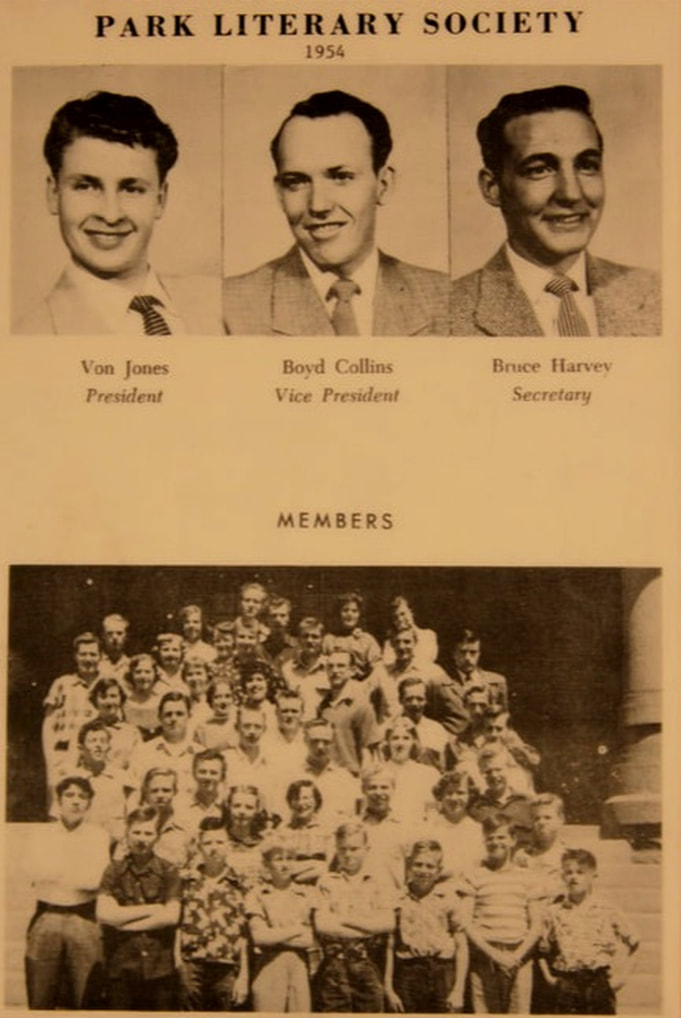

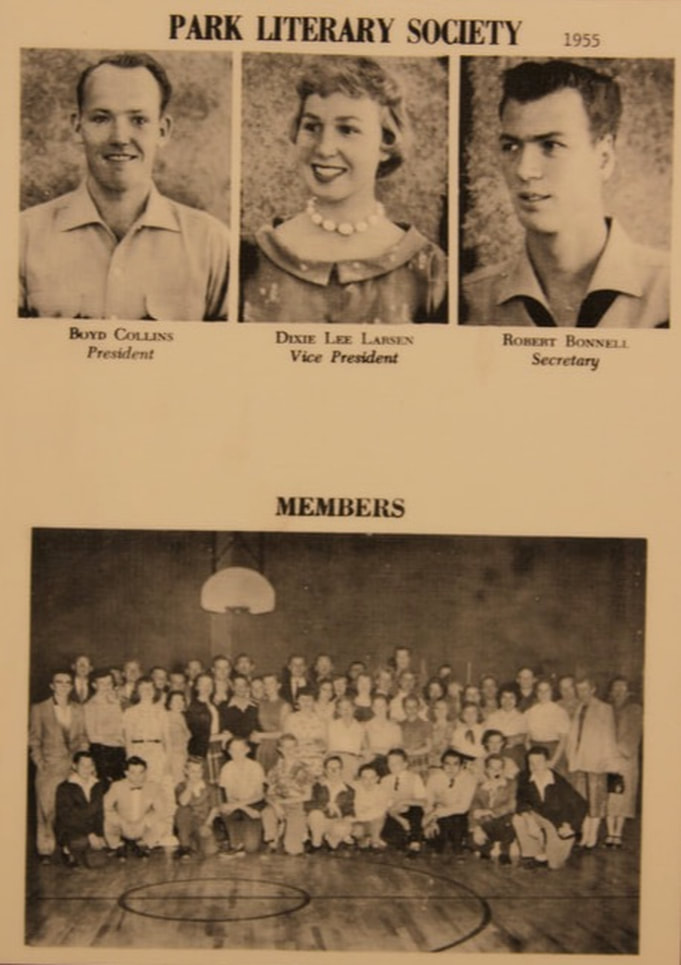

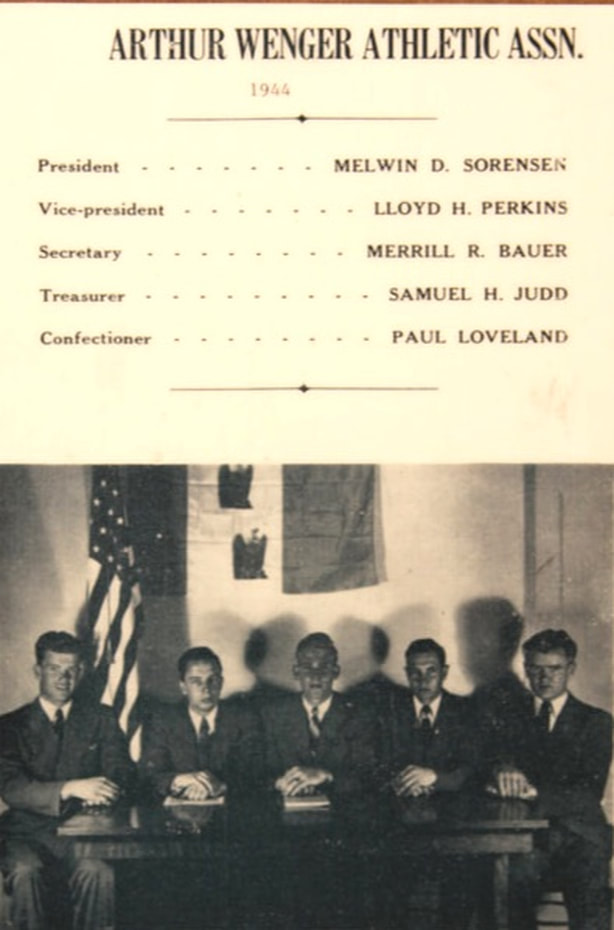

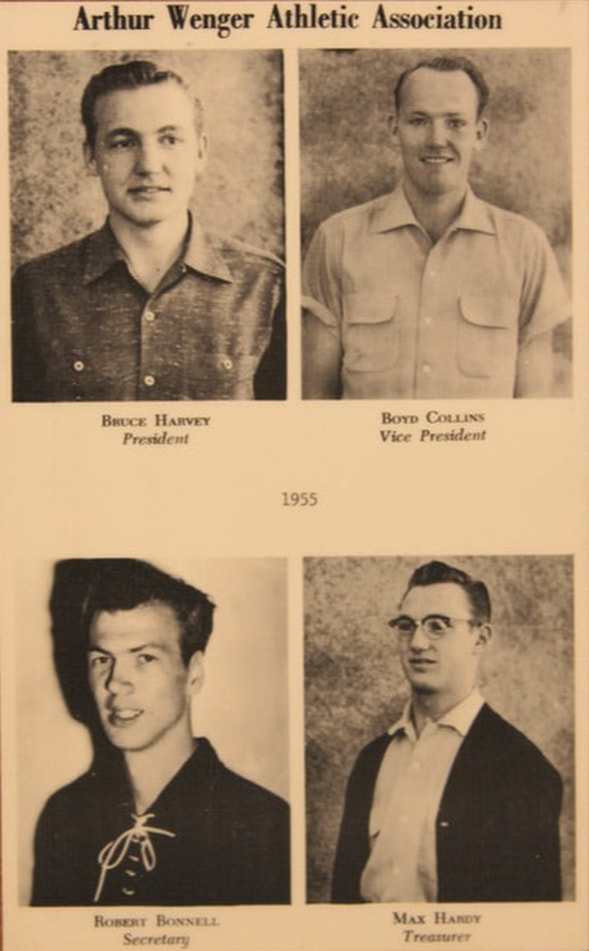

According to the Alumni Reunion booklets of 1976 and 1984, students at the Utah School for the Deaf had the opportunity to participate in extracurricular activities after school. These activities included the Park Literary Society, Arthur Wenger Athletic Association, Drama Club, Spur Club, Ski Club, Student Body Government, Junior NAD, Student Council, various athletic programs, as well as Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. Most of the students were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and attended church services at the Ogden Branch for the Deaf on Sundays and Tuesday nights. However, non-LDS students attended Protestant chapel services (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Booklet, 1976; A Century of Memories: Utah School for the Deaf 100th Year Anniversary Alumni Reunion Booklet, 1984).

The three most prominent clubs on campus were the Park Literary Society, the Arthur Wenger Athletic Association, and the Spur Club.

The three most prominent clubs on campus were the Park Literary Society, the Arthur Wenger Athletic Association, and the Spur Club.

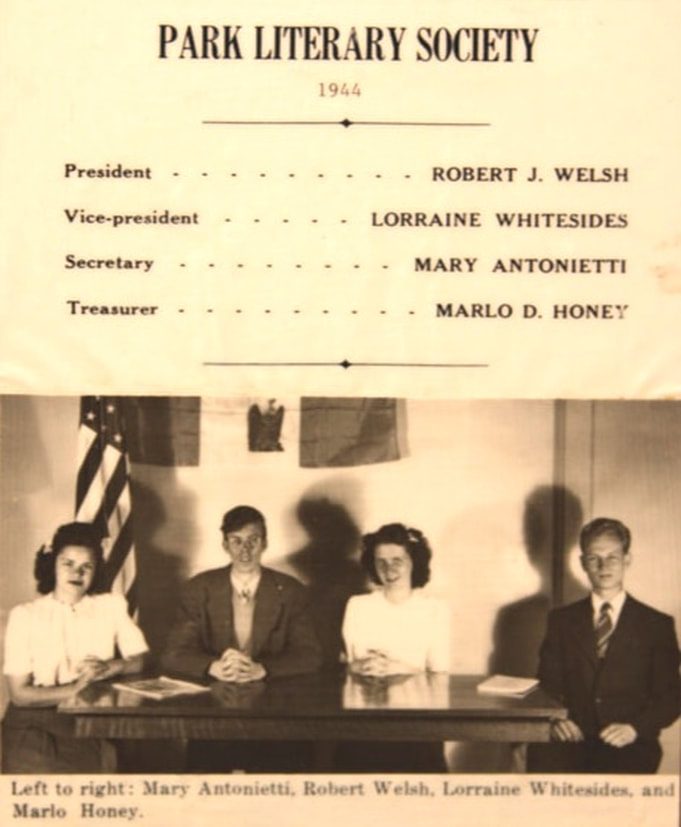

The Park Literary Society

In 1897, a year after the Utah School for the Deaf moved to Ogden from Salt Lake City, the Park Literary Society was formed to honor Dr. John R. Park, the President of the University of Deseret (now University of Utah), where the Deaf students held him in high regard. The Park Literary Society was the first club at the university and consisted of students aged between fourteen and seventeen who met every two weeks throughout the school year to improve their creative writing and acting skills, as well as their appreciation of literature. The society also provided a platform for students to practice their debating skills on a range of subjects. Students had to prepare their presentations, stories, plays, and debates without any assistance from their teachers (Roberts, 1994).

The "Eaglets" magazines published by the Utah School for the Deaf featured several debate topics, including whether "Lincoln was a greater man than Washington," "the United States should recognize the independence of Cuba," and "boys have more pleasure than girls." Judges, selected from among teachers and members of the Utah Deaf community, determined the debate winners. Debate helped students improve their communication, public speaking, teamwork, organizational skills, and world knowledge through reading (Roberts, 1994; First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Booklet, 1976; A Century of Memories: Utah School for the Deaf 100th Year Anniversary Alumni Reunion Booklet, 1984). Unfortunately, today's boys and girls miss out on such a great experience.

The Park Literary Society Produced

"The House of Rimmon" Play

"The House of Rimmon" Play

In 1921, the Park Literary Society showcased the creative abilities of the Deaf community in "The House of Rimmon." Arthur W. Wenger, a 1913 Utah School for the Deaf graduate, directed the play based on a Biblical story, with Elsie Christiansen, also Deaf, and a 1907 Utah School for the Deaf graduate providing assistance. The play's first performance in the school chapel was a huge success, prompting a repeat performance at East High School in Salt Lake City. Admission was free, and the crowd gave a standing ovation, highlighting the play's impact. This production not only showcased the abilities of Deaf people but also played a crucial role in raising public awareness about their potential (White, The Silent Worker, June 1920; Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921; UAD Bulletin, Summer 1964).

On September 5, 1956, representatives from the Utah Association of the Deaf and the Utah School for the Deaf met and decided to close the Park Literary Society (Sanderson, The Utah Eagle, October 1956). The reason for society's closure is unclear.

On September 5, 1956, representatives from the Utah Association of the Deaf and the Utah School for the Deaf met and decided to close the Park Literary Society (Sanderson, The Utah Eagle, October 1956). The reason for society's closure is unclear.

Did You Know?

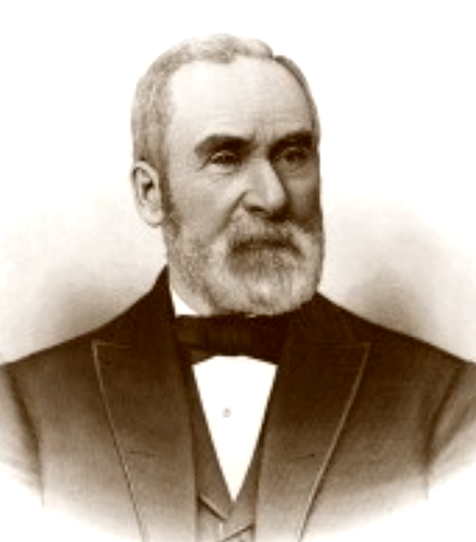

Dr. John R. Park played a significant role in supporting the Deaf community in Utah. In 1884, two parents of Deaf children, John Beck and William Wood, petitioned the then-Territory of Utah's Legislature to establish a state school for the deaf. The Legislature granted their request and assigned the task to Dr. Park, who was then the president of the University of Deseret. Dr. Park arranged for the university to establish a class for Deaf students and hired Henry C. White, a Deaf individual from Boston, to lead the program. Dr. Park showed a strong interest in this work throughout his life. For eight years, he served as the head of the Utah School for the Deaf. He recognized the need for the school's independence from the university and used his influence to ensure it happened. When the school became independent and moved to Ogden, he was overjoyed. He was a guest during his visit to the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, and the students remembered him. Even shortly before his death, he maintained the same enthusiasm for the school's well-being, which USD employees noted during a visit to his Salt Lake City office. Dr. Park was president of the University of the Territory and State for almost 25 years. He was born on September 30, 1835, and passed away on September 30, 1900 (Metcalf, The Utah Eagle, October 15, 1900; The Utah Eagle, October 15, 1900).

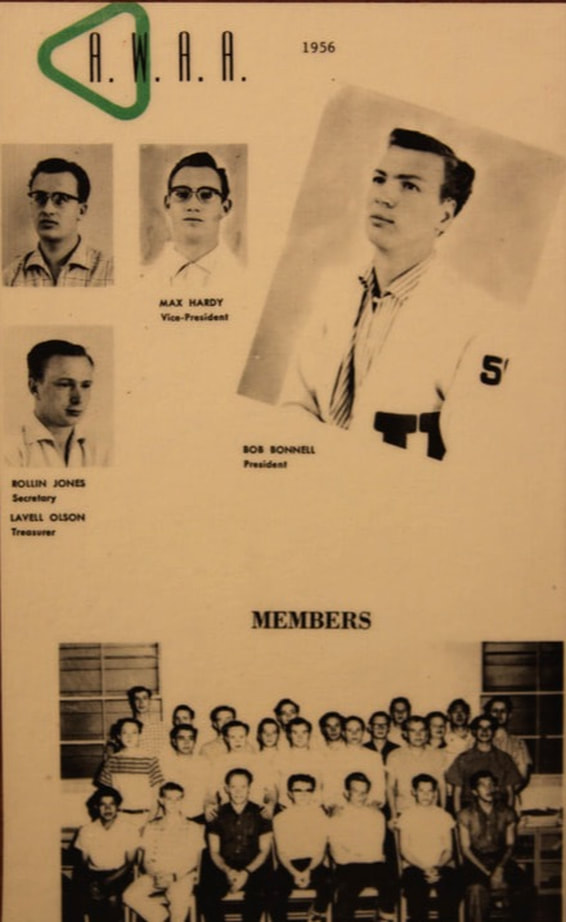

The Arthur Wenger Athletic Association

The Arthur Wenger Athletic Association (AWAA) was a club for older boys founded and named after Arthur W. Wenger, a 1931 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf. The club was active from 1919 to 1956 and aimed to promote social growth and fellowship among boys through physical activities (Robert, 1994). Students raised funds for the club by selling candy on the school campus under AWAA. However, the club ceased operations on September 5, 1956, when representatives from the Utah Association of the Deaf and the Utah School for the Deaf met for a conference and voted to close the Arthur Wenger Athletic Association. The $1,000.00 raised by the club was then used as a scholarship fund for the Utah Association of the Deaf Scholarship Fund. This fund later became the Utah Scholarship Foundation for the Deaf and the Ned C. Wheeler Scholarship Foundation for the Deaf (Sanderson, The Utah Eagle, October 1956).

The Spur Club

The Spur Club was an organization for older females that promoted school activities through sponsorship. Along with the clubs, the Utah School for the Deaf hosted an annual formal banquet to recognize students who excelled in their service. Boy and Girl Scout troops also participated in their designated programs and activities (Roberts, 1994).

According to Roberts (1994), extracurricular activities primarily teach students necessary social skills and foster the development of lasting connections. This laid the foundation for the eventual formation of Deaf communities in Utah and Idaho. The Utah School for the Deaf provided a sense of community for Deaf students for the first time, which led to the creation of Deaf organizations that offered support and social activities for these individuals.

The Annual May Festival

of the Utah School for the Deaf

of the Utah School for the Deaf

The Utah School for the Deaf organized the first May Festival in 1909 and continued it annually until 1936. During the festival, students from the school showcased their remarkable dancing skills, which attracted a large audience. One performance alone drew 5,000 spectators (Pace, 1946). The ninth edition of the May Festival, which had a theme of "The Story of the Deaf," was the most successful pageant. In May 1920, the Utah School for the Deaf held this pageant on its campus and later on the lawn of Liberty Park in Salt Lake City, Utah. During the pageant, students dressed up in costumes representing various nationalities and portrayed the Deaf community's struggles against 'intolerence and neglect.' The central message of the pageant was that through education, the Deaf community can overcome these obstacles and achieve happiness and success (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921).

Mona Leckliter, Vida Crawford, Elsie Lamb, Gladys Jones, and Coraline Wood performed as soloists in a pageant. Arthur W. Wenger, a 1913 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf, praised the beautiful performance of these dancers, who represented the five senses of sight, taste, touch, smell, and hearing. As the dancers performed, a group of girls entered, seeking the blessing of the five senses they had received as a gift. With excitement and thankfulness, the girls and their senses danced in unison.

However, the girls lost their hearing and separated from their companions. Edna Wright, who portrayed the "Maiden" as "Deaf," passionately pleaded for the blessing of the five senses. Only four of the senses could bestow blessings on the "Maiden." When the "Maiden" discovered she was deaf, she was heartbroken, but the knowledge came to her rescue, summoning nature in the form of butterflies, birds, and flowers to assist her. The "Maiden" was overjoyed.

The pageant highlighted the narrative of the Deaf community's struggle to seek recognition of their rights. Arthur W. Wenger then said that, just before the pageant's end, the dancers showed examples of the many nations. Each was a letdown until the "Maiden" of the Stars and Stripes emerged from the flag's folds. Arthur remarked, "She gave liberty, equity, and prosperity to all." He says that "her graceful dancing and real expression attracted the people who loved her and all the children who helped her" (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921, p. 113).

The pageant highlighted the narrative of the Deaf community's struggle to seek recognition of their rights. Arthur W. Wenger then said that, just before the pageant's end, the dancers showed examples of the many nations. Each was a letdown until the "Maiden" of the Stars and Stripes emerged from the flag's folds. Arthur remarked, "She gave liberty, equity, and prosperity to all." He says that "her graceful dancing and real expression attracted the people who loved her and all the children who helped her" (Wenger, The Silent Worker, January 1921, p. 113).

Dressed in flowing chiffon gowns for their role in one of the

USD’s famous May Festivals in 1920 are, left to right, front,

Corline Wood, Ellen Lusk, Gladys Jones; center, Verda

Williams, Vida Crawford, Catherine Crawford, Eda Wright,

Irene Linderman; back, Mary Erying, Lona Thompson, Mona

Leckliter, Florence Funk, and Violet Taylor. The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963

The May Festival was held

on the Utah School for the Deaf campus in 1910

on the Utah School for the Deaf campus in 1910

Helen Keller’s Visit to the

Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind

Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind

On March 14, 1941, Helen Keller, a well-known Deaf and Blind woman, and her companion and interpreter, Polly Thompson, and business manager, Ida Hirst-Gifford, visited the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind (USDB). Before arriving at the school, she had traveled to Utah on behalf of the American Foundation for the Blind, where she testified in front of the legislature to support blind adults. Helen Keller also spoke before a crowd of 5,000 people at the Mormon Tabernacle.

During her visit to USDB, Helen Keller gave a speech in the Main Building chapel, where students gathered to listen to her remarks. The USDB Superintendent, Frank Driggs, assisted with the interpreting, while Polly Thompson, Helen's interpreter, communicated with her using speech and the manual alphabet. When a student spelled out in Helen's hand, asking her, "What is the most outstanding thing you have found on your visit to Utah?" she immediately replied, "The good will toward the adult blind" (The Utah Eagle, March 1941, p. 11).

During her visit to USDB, Helen Keller gave a speech in the Main Building chapel, where students gathered to listen to her remarks. The USDB Superintendent, Frank Driggs, assisted with the interpreting, while Polly Thompson, Helen's interpreter, communicated with her using speech and the manual alphabet. When a student spelled out in Helen's hand, asking her, "What is the most outstanding thing you have found on your visit to Utah?" she immediately replied, "The good will toward the adult blind" (The Utah Eagle, March 1941, p. 11).

One of the students, Kleda Barker Quigley, remembers the event from her school days when Helen Keller accompanied Polly Thompson to the assembly chapel and delivered a speech in her voice to all the Deaf and blind students. Kleda was amazed by Helen's intelligence and the speed at which she signed with her interpreter, Polly, and astonished that Helen had overcome her double disabilities of being deaf and blind to the best of her ability. Years later, in 2014, Kleda talked about Helen Keller on videophone with some Utah School for the Deaf alums, including Fred Richins, G. Leon Curtis, Jay A. Barker, her brother, Winona Anderson, Gerry Shepard, and others. Leon, Kleda's classmate, asked Helen whether she would rather be deaf or blind over the video call. "Blind," she said. In her interview, Kleda stated that most Deaf people prefer to be deaf rather than blind. Nevertheless, Helen's visit positively impacted Kleda, and she was grateful for the experience (Kleda Quigley, personal communication, April 15, 2015).

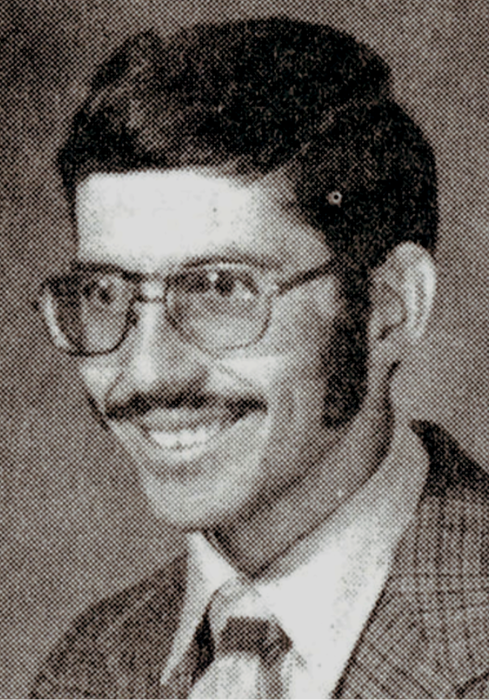

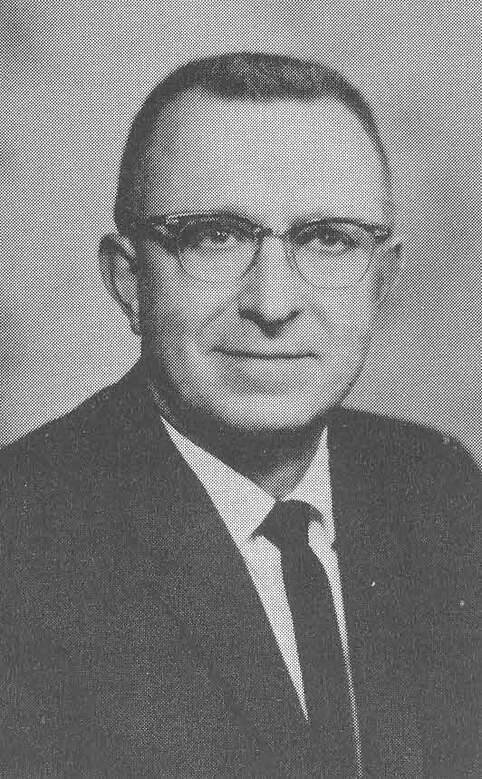

The Burdett’s Picnic and Boating Party

In 1953, Kenneth C. Burdett, a Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, organized a picnic and boating party for high school students during the summer. Eleanor Kay Kinner, a member of the class of 1954, wrote an article about the event titled "Burdett's Picnic and Boating Party," which was published in the Utah Eagle magazine. In her article, Kinner described how much fun they had at the party and how Burdett was not only an inspirational youth leader but also a great teacher.

“During the summer of 1953, it was so hot that the Utah School for the Deaf high school students always drank lemonades or cold drinks. The lawns and plants were dry because they had so few showers. However, sometimes there was a little rain at night, but not during the day. They surely had a hard time watering the plants, lawns, and flowers so they would grow beautifully. Those who had jobs came home and watered in the evening. They went swimming often to get cool.

On August 2, they received an invitation from the Burdetts to go boating and picnicking. They were filled with excitement, and the invitation extended to some girls and boys who lived far away from Ogden. Some of them came to Ogden so they might go to Pine View Lake together the Sunday after Peter and Sally [Green]’s wedding.

“During the summer of 1953, it was so hot that the Utah School for the Deaf high school students always drank lemonades or cold drinks. The lawns and plants were dry because they had so few showers. However, sometimes there was a little rain at night, but not during the day. They surely had a hard time watering the plants, lawns, and flowers so they would grow beautifully. Those who had jobs came home and watered in the evening. They went swimming often to get cool.

On August 2, they received an invitation from the Burdetts to go boating and picnicking. They were filled with excitement, and the invitation extended to some girls and boys who lived far away from Ogden. Some of them came to Ogden so they might go to Pine View Lake together the Sunday after Peter and Sally [Green]’s wedding.

"The day began cold and rainy and they thought that they might not be able to go there. While they stayed at the Burdett home, they waited and waited for the rain to stop. Suddenly, the rain stopped, and the sun shone very brightly about noon. They thought the weather was queer. When the sun shone through the window onto the floor, they were ready, and started for Pine View Lake.

Some of them went water-skiing and surf boarding. Some of the girls and boys went riding in the boat with Kenneth Burdett. Kenneth Kinner held onto the rope and went water skiing. They were nonplussed that Max Hardy could water ski and ride a surfboard. He just held onto the rope and rode the waves, then went water skiing at once. He was successful although that was his first time. Von Jones, Dona Mae Dekker, Lawana Simmons, and Bruce Harvey tried to learn how to control themselves while water skiing. Some fell down all the time, but some were successful. Dixie Lee Larsen and Kay Kinner water-skied well because they had done this before at Bear Lake. They had fun going water skiing and surf riding.

At the beach, they rested and the Burdetts treated them to cold drinks. They took sunbaths for a while. They had fun going water skiing and surf riding. They fell and tried to manage themselves.

In the evening, the students went to the Burdetts’ for a barbecue in their yard. It was delicious and they did enjoy going to the picnic and boating party. It was all very interesting for them. Marion Brown and her boyfriend were with them” – Kay Kinner (Kinner, The Utah Eagle, October 1953).

Some of them went water-skiing and surf boarding. Some of the girls and boys went riding in the boat with Kenneth Burdett. Kenneth Kinner held onto the rope and went water skiing. They were nonplussed that Max Hardy could water ski and ride a surfboard. He just held onto the rope and rode the waves, then went water skiing at once. He was successful although that was his first time. Von Jones, Dona Mae Dekker, Lawana Simmons, and Bruce Harvey tried to learn how to control themselves while water skiing. Some fell down all the time, but some were successful. Dixie Lee Larsen and Kay Kinner water-skied well because they had done this before at Bear Lake. They had fun going water skiing and surf riding.

At the beach, they rested and the Burdetts treated them to cold drinks. They took sunbaths for a while. They had fun going water skiing and surf riding. They fell and tried to manage themselves.

In the evening, the students went to the Burdetts’ for a barbecue in their yard. It was delicious and they did enjoy going to the picnic and boating party. It was all very interesting for them. Marion Brown and her boyfriend were with them” – Kay Kinner (Kinner, The Utah Eagle, October 1953).

Students went boating with Kenneth and Afton Burdett, Deaf teachers at

Pineview Reservoir, 1953. Standing L-R: Kay Kinner, Marion Brown,

Bruce Harvey, Dixie Lee Larsen, Afton Burdett, Kenneth Burdett, Max

Hardy, Donna Mae Dekker, Leon Curtis, Von Jones, Lawana Simmons.

Sitting L-R: Kenneth Kinner and Ronald Burdett

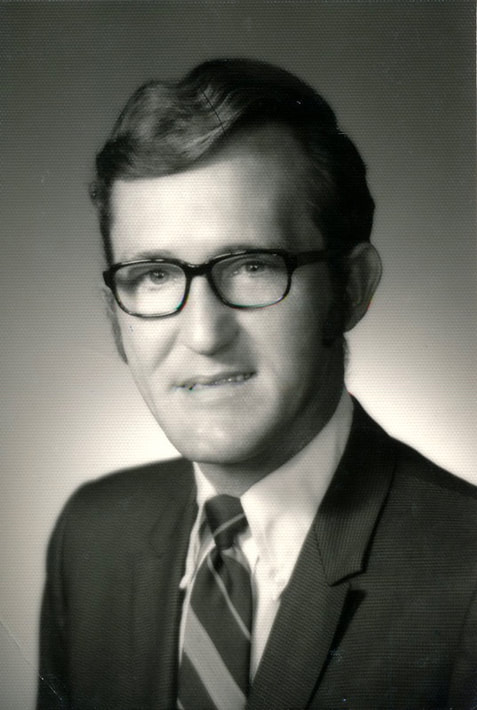

Kenneth C. Burdett dedicated his life to the Utah School for the Deaf. He worked at the Utah School for the Deaf for four decades, from 1934 to 1974, and spent an additional fifty-two years as a student, boy's supervisor, head basketball coach, athletic director, teacher, printing instructor, and curriculum coordinator. Kenneth was also a member of the Utah Association for the Deaf, the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, and the Golden Spike Athletic Club of the Deaf (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 23, 1974). He was widely respected for his unwavering support for student athletics, deep affection for his students, and inspiring leadership that encouraged each student's personal growth. Kenneth was a highly regarded teacher and coach who inspired young people and all those he encountered (Dr. Robert Sanderson and Valerie Kinney, personal communication, July 8, 2011).

Holiday Celebrations at

the Utah School for the Deaf

the Utah School for the Deaf

Holidays were important social events at the Utah School for the Deaf in its early years. The school served and entertained the students during their Thanksgiving stay. They usually only returned home for the Christmas holidays (Roberts, 1994; Evans, 1999). In 1913, the school allowed students who lived nearby to return home for the Thanksgiving holiday weekend (Evans, 1999).

The school also observed Arbor Day, Valentine's Day, Easter, and other holidays. The teachers prepared the Arbor Day activities, Valentine's socials, and other holiday events (Roberts, 1994). The social events took place in Salt Lake City during the school year. USD Superintendent Frank Metcalf and teachers sponsored a masquerade dance and other events. He also frequently sponsored social events in the spring and fall, where teachers and older students socialized. People who attended these social gatherings formed several marriages (Roberts, 1994).

Given that the majority of students resided on campus, birthday celebrations took on a special significance. The school would organize birthday parties for both teachers and students, fostering a sense of community and familial bonds. Additionally, the Metcalf children would often extend invitations to many students for their birthday parties, further enhancing the familial atmosphere (Roberts, 1994).

The school also observed Arbor Day, Valentine's Day, Easter, and other holidays. The teachers prepared the Arbor Day activities, Valentine's socials, and other holiday events (Roberts, 1994). The social events took place in Salt Lake City during the school year. USD Superintendent Frank Metcalf and teachers sponsored a masquerade dance and other events. He also frequently sponsored social events in the spring and fall, where teachers and older students socialized. People who attended these social gatherings formed several marriages (Roberts, 1994).

Given that the majority of students resided on campus, birthday celebrations took on a special significance. The school would organize birthday parties for both teachers and students, fostering a sense of community and familial bonds. Additionally, the Metcalf children would often extend invitations to many students for their birthday parties, further enhancing the familial atmosphere (Roberts, 1994).

School Events and Trips

The Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City allowed its students to participate in various events and field trips. For instance, the students visited the circus before and after the school moved to Ogden. They also enjoyed winter activities such as sledding and ice skating. When the school was located in Salt Lake City, the students would go sledding on the hills between the school and the future site of the Utah Capitol. After the school moved to Ogden, the gardener kept an ice rink on campus for most of the years so that the students could enjoy ice skating (Robert, 1994).

John Beck, a co-founder of the Utah School for the Deaf, owned Beck's Hot Springs, located north of Salt Lake City. John Beck's three sons—Joseph, John A., and Jacob—and other older boys used to frequent Beck's Hot Springs before the school relocated to Ogden (Robert, 1994).

Later on, most of the Deaf students used to go back home for Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter (Robert, 1994).

John Beck, a co-founder of the Utah School for the Deaf, owned Beck's Hot Springs, located north of Salt Lake City. John Beck's three sons—Joseph, John A., and Jacob—and other older boys used to frequent Beck's Hot Springs before the school relocated to Ogden (Robert, 1994).

Later on, most of the Deaf students used to go back home for Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter (Robert, 1994).

The students and staff would occasionally go on nature walks and shopping trips together. These trips were beneficial as they provided opportunities for education and a change of scenery for everyone involved (Roberts, 1994).

During one of these trips, the students had the chance to meet Dr. James Talmage, a professor at the University of Utah. Dr. Talmage's blind brother, Albert Talmage, was a student at the Utah School for the Blind. Dr. Talmage was already familiar with several students from the school due to his past affiliation with the institution when it was still housed with the University of Utah (Robert, 1994).

During one of these trips, the students had the chance to meet Dr. James Talmage, a professor at the University of Utah. Dr. Talmage's blind brother, Albert Talmage, was a student at the Utah School for the Blind. Dr. Talmage was already familiar with several students from the school due to his past affiliation with the institution when it was still housed with the University of Utah (Robert, 1994).

According to the Utah Eagle, the voyage took place in Ogden Canyon from 1900 to 1901.

“Some of the large boys went up to the mouth of Ogden Canyon with Mr. Crandall the other day. They wanted to look at the bridge which was recently destroyed by a rock falling from the immense cliff at the mouth of the canyon. They met Dr. Talmage, formerly president of the University of Utah. He was to examine the tunnel, the cliff, the fissure and the water pipe and report to the electric Power Plant Company regarding the cause of the break and the proper course to pursue to repair the damage done. Dr. Talmage is a learned geologist and a very prominent scientist (p. 70).”

Several influential figures visited the Utah School for the Deaf and struck up friendships with the students. Among these figures was David O. McKay, who visited the school while teaching at Weber Stake Academy and serving in the Utah State Legislature. Later, he was elected President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Robert, 1994).

“Some of the large boys went up to the mouth of Ogden Canyon with Mr. Crandall the other day. They wanted to look at the bridge which was recently destroyed by a rock falling from the immense cliff at the mouth of the canyon. They met Dr. Talmage, formerly president of the University of Utah. He was to examine the tunnel, the cliff, the fissure and the water pipe and report to the electric Power Plant Company regarding the cause of the break and the proper course to pursue to repair the damage done. Dr. Talmage is a learned geologist and a very prominent scientist (p. 70).”

Several influential figures visited the Utah School for the Deaf and struck up friendships with the students. Among these figures was David O. McKay, who visited the school while teaching at Weber Stake Academy and serving in the Utah State Legislature. Later, he was elected President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Robert, 1994).

Maud May Babcock, the University of Utah's first female faculty member and founder of the Departments of Speech, Physical Education, and University Theater, served on the school's board of trustees for twenty-two years. The Babcock Theater, the first college dramatic club in the United States, was renamed after her. She traveled to the east in 1904 to study communication methods at other schools and eventually lobbied for additional funding for the school's new programs. In addition, she came to the school regularly to share her experiences with the students (Robert, 1994; Maud Babcock – Wikipedia).

Edwin A. Stratford chaired the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf for several years. After the school was separated from the University of Utah and relocated to Ogden, he was appointed to stay on the board. In 1896, he was also the superintendent of the students' Sunday School for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at the school in Ogden.

In conclusion, these four individuals and others significantly impacted USD students and helped raise their awareness of the institution among their friends and members of the Utah State Legislature (Robert, 1994).

In conclusion, these four individuals and others significantly impacted USD students and helped raise their awareness of the institution among their friends and members of the Utah State Legislature (Robert, 1994).

Legislative Leadership Opportunity

During Utah's territorial period, students at the Utah School for the Deaf had the opportunity to serve as legislative leaders. They were trained to lobby politicians and request funding for their educational pursuits. Even after Utah became a state in 1896, the students continued collaborating with legislators to secure funding for the school and its programs. Teachers organized an "exhibition" on the school campus every year to showcase the students' achievements and invite legislators to witness their abilities. This event provided the students with a chance to interact with hearing individuals while also demonstrating their accomplishments. They were able to explain to legislators the importance of the school program. Ultimately, this program boosted the students' self-confidence (Roberts, 1994).

In January 1896, the state legislature organized an exhibition where students displayed their educational skills, performed songs, and recited poems and readings. The Utah State Capitol building provided a tour for the students, educating them about the legislative process and its implementation. They also had meetings with several government officials. As a result, the students gained an understanding of the functions of government, including the legislative (House and Senate), executive (Governor), and judicial (Courts) branches, among other things. During the tour, the students learned about things their parents might not have known (Roberts, 1994). Many of them rose to leadership positions within the state because of the legislative leadership skills they acquired in school. In addition, they contributed their leadership skills to the Utah Association of the Deaf, covering a wide range of advocacy issues such as auto insurance, traffic safety, anti-peddlers, education, early intervention, employment, rehabilitation services, interpreting services, health care, technology, and telecommunications, youth leadership, and various other issues.