The Utah Deaf Education Controversy:

Total Communication Versus Oralism

at the University of Utah

Total Communication Versus Oralism

at the University of Utah

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

I had the opportunity to learn more about Dr. Grant B. Bitter's profound impact on deaf education in Utah through my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, a 1954 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf and the father of two Deaf children, Duane and Deanne. While learning about Dr. Bitter as a parent of two Deaf children myself, I am so grateful to Jeff W. Pollock, who played an essential role in uncovering, preserving, and promptly responding to my inquiry about Dr. Bitter's invaluable documents. His master's degree research at the University of Utah was crucial in bringing to light Dr. Bitter's significant documents, which he generously donated to the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah upon his retirement on June 30, 1987. He also shared his findings about Dr. Bitter's paper at the 2005 Utah Association for the Deaf Conference. Jeff's 2005 discovery of Dr. Bitter's meticulous documentation, along with my 2006 manuscript of his oral and mainstreaming impact on deaf education in Utah, paved the way for the establishment of this website, a digital tribute to Dr. Bitter's remarkable preservation.

Jeff W. Pollock, a Deaf Education Advocate, wrote "The Utah Deaf Education Controversy: Total Communication Versus Oralism at the University of Utah" for his Master's level "History of Higher Education" at the University of Utah, dated May 4, 2005.

Jeff, your dedication and passion for this project have not gone unnoticed. I am truly grateful for your invaluable contribution.

Thank you, and enjoy reading!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Jeff W. Pollock, a Deaf Education Advocate, wrote "The Utah Deaf Education Controversy: Total Communication Versus Oralism at the University of Utah" for his Master's level "History of Higher Education" at the University of Utah, dated May 4, 2005.

Jeff, your dedication and passion for this project have not gone unnoticed. I am truly grateful for your invaluable contribution.

Thank you, and enjoy reading!

Jodi Becker Kinner

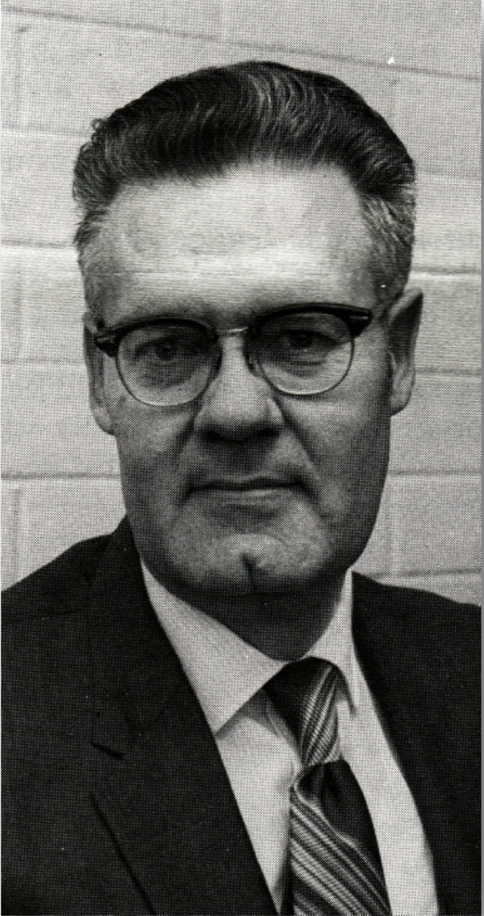

Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which inspired his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which inspired his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter, who opposed anyone who stood in the way of his goals of promoting oral and mainstream education, has formally requested the job removal of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, both respected advocates for sign language. He believed they were interfering with his mission. Additionally, he expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, feeling it did not align with his educational goals. He also asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected committee chairperson, to resign because she invited representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he saw as a shift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf, in the face of Dr. Bitter's opposition, demonstrated remarkable resilience, marking a significant turning point in their history and inspiring others with their strength and determination.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. His journey began at the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked as a teacher and curriculum coordinator. His passion for education led him to become a director and professor in the Teacher Training Program, where he focused primarily on oral education under the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. Dr. Bitter also served as the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

Dr. Bitter taught the Teacher Training Program within the Special Education Department at the University of Utah for 19 years, starting in 1968, focusing on oral education. His ambition to promote oral and mainstreaming sparked a heated controversy between oral and sign language, particularly with the Utah Association for the Deaf. Dr. Bitter's unwavering commitment also had a huge impact on the oral philosophy movement at the Utah School for the Deaf, as well as the integration of deaf education into mainstream society.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

Dr. Bitter taught the Teacher Training Program within the Special Education Department at the University of Utah for 19 years, starting in 1968, focusing on oral education. His ambition to promote oral and mainstreaming sparked a heated controversy between oral and sign language, particularly with the Utah Association for the Deaf. Dr. Bitter's unwavering commitment also had a huge impact on the oral philosophy movement at the Utah School for the Deaf, as well as the integration of deaf education into mainstream society.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, there was a national shift in deaf education, moving away from the oral method and towards an approach that included sign language, known as Total Communication. In 1960, Dr. William Stokoe, a scholar and hearing professor at Gallaudet College, published a dissertation recognizing American Sign Language (ASL) as an official language with its own syntax, morphology, and structure (Wikipedia: William Stokoe). Despite Dr. Stokoe's research, many professionals in Utah's deaf education field continued to advocate for the oral approach, and the University of Utah's Teacher Training Program did not include sign language.

In 1971, the Utah Association for the Deaf, including Lloyd H. Perkins, Chairperson of the UAD Educational Committee, asked in writing for a review of the Teacher Training Program (L. Perkins, personal communication, no date). On December 7, 1971, Dr. Erdman, the Department of Special Education Chairperson, wrote back to affirm to Lloyd that there would be a meeting on December 13 to review the Teacher Training Program. Dr. Stephen Hencley, the Dean of the Graduate School of Education, responded to Lloyd's letter on December 16, 1971, assuring him that the Teacher Training Program would undergo curriculum changes and incorporate a sign language component (Dr. Erdman, personal communication, December 6, 1971).

Four years later, on July 23, 1974, Dr. Jay J. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a sign language interpreter, the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, and the crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community, followed up with Dr. Erdman, the Chairperson of the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. He requested a report to confirm the implementation of a comprehensive communication curriculum in the Teacher Training Program. In response, Dr. Erdman informed Dr. Campbell that the Teacher Training Program hired Gene Stewart, a Children of Deaf Adults (CODA) and vocational rehabilitation counselor, in 1972 to teach a sign language course. Dr. Erdman's letter also included the new policy, as stated: "All students who are preparing to become teachers of the hearing impaired are required to master the basic manual communication competencies through involvement in one or both of the above described classes or be able to demonstrate those competencies if they have already had previous manual communication experiences and/or coursework in that area" (Dr. Erdman, personal communication, p. 2, August 15, 1974). There was a divergence between the Deaf Association for the Deaf and the Special Education Department regarding the extent to which the program would offer total communication courses. Apparently, the Utah Association for the Deaf expected a complete Total Communication Program, but the Teacher Training Program disagreed with this expectation.

In 1977, the Utah Association for the Deaf continued to advocate for including a total communication curriculum in their program. They urged University President Alfred C. Emery and other administrators to review the Teacher Training Program, modify the curriculum, and include sign language as an equal component of oralism. In late August or early September 1977, UAD representatives met with Dr. Pete D. Gardner, Vice President for Academic Affairs at the University, to present a 9-point list of concerns regarding the Teacher Training Program, as shown in the section below. During the meeting, Lloyd Perkins and other UAD representatives requested to meet with President Emery to present their concerns. However, Dr. Gardner responded by sending a letter to Lloyd Perkins' wife, Madeleine Burton Perkins, who served as an interpreter for the meeting. In the letter, Dr. Gardner informed them that a meeting with President Emery would be unproductive and that Dr. Bitter had not violated any academic standards (P.D. Gardner, personal communication, September 14, 1977).

President Emery's refusal to meet sparked controversy when W. David Mortensen, a well-known political activist and president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, organized two protests. The first protest took place on November 18, 1977, outside the Utah State Office of Education, and the second on November 28, 1977, in front of the Park Building on the University of Utah campus. The protests were a response to several grievances, including an unfair preference for oral-only education, a bias against the total communication method of teaching, a preference for day schools, a lack of Deaf representation on the Advisory Committee, and a failure to listen to the Utah Association for the Deaf. On November 28, approximately twenty Deaf people gathered in front of the Park Building to protest the university's handling of their concerns. M. J. Lewis published a letter to the Deseret News, stating that "Dr. Bitter has so brainwashed and put fear into parents that their children will never be able to function as normal human beings" (Lewis, Deseret News, November 28, 1977; Jeff Pollock, The Utah Deaf Education Controversy, May 4, 2005).

During the protest, Dr. Bitter's still stance on how Deaf students should be educated in oralism and his rejection of the Utah Association for the Deaf's demand to include sign language in his curriculum. In response to the Utah Association for the Deaf protest, Dr. Bitter said, "We are trying to be fair and meet individual needs" (Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, November 29, 1977, p. 1; Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, December 2, 1977). He responded that he supported an oral-only approach because he believed it was the most effective way to help Deaf children integrate into society (Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, November 29, 1977, p. 1). Dr. Bitter further contended that oralism would help Deaf children develop a positive self-concept and prepare them for mainstream life independently without relying on a sign language interpreter. He further clarified that the Teacher Training Program included sign language classes. Dr. Bitter noted that the university had met its obligations to the Utah State Board of Education by incorporating total communication opportunities in its oral curriculum (Graduate School of Education, November 28, 1977; Hunt, The Daily Utah Chronicle, December 2, 1977).

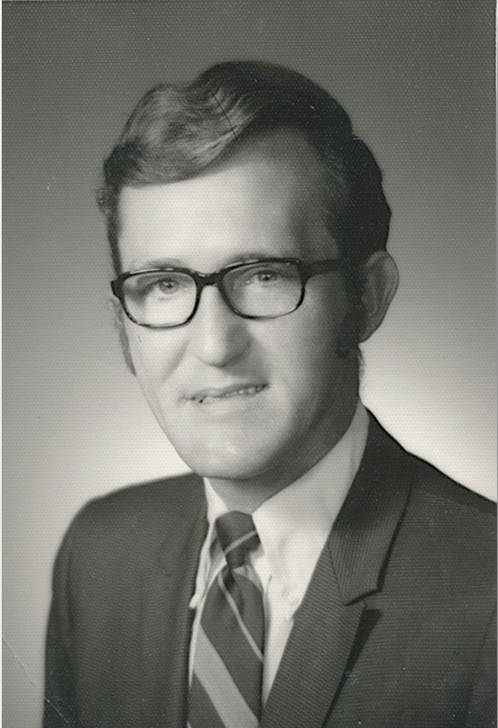

The protests, led by UAD President Mortensen, caught the attention of the Utah State Board of Education. In April 1979, they passed a motion directing the University of Utah to hire a faculty member to teach a total communication class to prospective deaf education teachers (The Silent Spotlight, June 1979; Jeff Pollock, The Utah Deaf Education Controversy, May 4, 2005). From 1979 to 1985, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson taught ASL (then total communication) as well as the social, psychological, and cultural aspects of deafness as an adjunct professor in the Division of Communication Disorders at the University of Utah.

On April 20, 1982, Utah State University approved a new deaf education major, marking a significant milestone in Utah's history of deaf education. This major allowed teacher candidates to study total communication skills, a crucial aspect of deaf education. Leading this program was Dr. Thomas C. Clark, the founder of SKI-HI, which served Deaf babies and toddlers. He was the hearing son of a Deaf father, John H. Clark, who graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1897 and became the first Utah graduate of Gallaudet College in 1902. Dr. Thomas C. Clark was also the second cousin of Elizabeth DeLong, who, like John H. Clark, also graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1897; was the first Utah graduate from Gallaudet College in 1902; and was the first female president of the Utah Association of the Deaf in 1909. However, it's important to note that funding was unavailable until 1985, when Utah State University established a preparation program to provide a total communication component.

Duane Kinner, the son of Deaf parents Kenneth and Ilene Kinner, was featured on the front cover of the SKI-Hi Model packet in 1974. The packet provided training through amplification and home intervention when visiting families with Deaf infants and toddlers.

Launching a Total Communication Program at Utah State University was a huge step forward for the Utah Association for the Deaf and the Utah Deaf community! Previously, the majority of total communication teachers in Utah were from other states, while the majority of oral teachers came from the University of Utah. In 1991, Dr. J. Freeman King, a newly hired hearing professor, transformed the Deaf Education Program at Utah State University from a Total Communication Program to a Bilingual-Bicultural Program (UAD Bulletin, October 1991).

In 2007, Dr. Karl R. White, a psychology professor at Utah State University, led the establishment of the Listening and Spoken Language program. Initially, this led to a heated debate between the Bilingual-Bicultural Program and the Listening and Spoken Language Program. Nonetheless, they coexisted and focused on their work within the same department.

Over the years, Dr. Bitter has remained a strong advocate for oralism and mainstreaming. The decline of education at the Utah School for the Deaf and the integration of more Deaf students into mainstream education saddened its alums. In Utah, the oral and mainstreaming movements have influenced deaf education since the early 1960s, with Dr. Bitter playing a key role. He used his influence and parental power to promote oralism in deaf education, making it difficult for the Utah Association for the Deaf to challenge him. After the Teacher Training Program in the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah closed in 1986, Dr. Bitter retired in 1987 (Bitter, A Summary Report for Tenure, March 15, 1985). Today, the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah offers a Specialization in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program. While the curriculum does include American Sign Language classes, it still places a greater emphasis on Listening and Spoken Language. This reflects the impact that Dr. Bitter, who passed away in 2000, continues to have on deaf education in Utah. To learn more about the evolving mainstreaming movement, visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective' webpage.

Dr. Bitter revealed in an interview with the University of Utah in 1987 that he had been the target of a vicious attack by the Utah Deaf community. Community leaders viewed him as a scoundrel who knew nothing about deafness. During this time, picketers gathered on the University of Utah campus and at the Utah State Office of Education, staging protests that included burning his effigy. The "Years of Controversy" paper also contains slanderous statements, detailed in Jeffrey W. Pollock's paper, like, "Jay J. Campbell will put Burbank down. Power is UAD" and "J.J. Campbell and R. Sanderson will throw Boyd Nielsen out of job in Utah, in America, and out of this world. UAD is Deaf power" (Grant Bitter, Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). It is clear that Dr. Bitter had little understanding of Deaf people's experiences in the oral and mainstreaming educational system. If only he had listened to their perspectives and understood what Deaf people went through.

Jeffrey W. Pollock's "The Utah Deaf Education Controversy: Total Communication and Oralism at the University of Utah" document above offers more details about the protest.

Dr. Bitter revealed in an interview with the University of Utah in 1987 that he had been the target of a vicious attack by the Utah Deaf community. Community leaders viewed him as a scoundrel who knew nothing about deafness. During this time, picketers gathered on the University of Utah campus and at the Utah State Office of Education, staging protests that included burning his effigy. The "Years of Controversy" paper also contains slanderous statements, detailed in Jeffrey W. Pollock's paper, like, "Jay J. Campbell will put Burbank down. Power is UAD" and "J.J. Campbell and R. Sanderson will throw Boyd Nielsen out of job in Utah, in America, and out of this world. UAD is Deaf power" (Grant Bitter, Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). It is clear that Dr. Bitter had little understanding of Deaf people's experiences in the oral and mainstreaming educational system. If only he had listened to their perspectives and understood what Deaf people went through.

Jeffrey W. Pollock's "The Utah Deaf Education Controversy: Total Communication and Oralism at the University of Utah" document above offers more details about the protest.

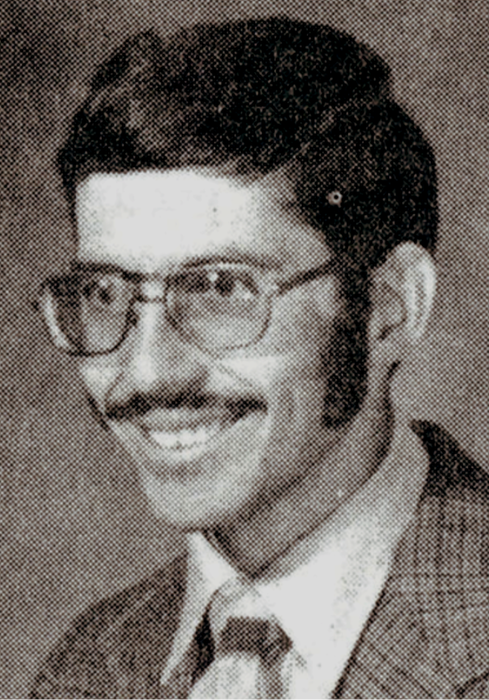

A Biography of Jeffrey W. Pollock

In 2007, Jeff Pollock established and directed the Davis Applied Technology College ASL-Interpreting Program. In various capacities, he has been a consultant for the Utah Interpreting Program since 1995, as a former member and chairperson, and (2012) co-chairperson of the UIP Advisory Board. Jeff’s career has included teaching ASL, Linguistics, and Deaf Studies at the high school, community college, and university levels, coordinating interpreting services for the University of Utah, and serving as an instructor at the ASL Teaching Program of the University of Utah. Jeff has a Bachelor of Science in Biology and a Master’s degree in Educational Leadership and Policy, and he is a Certified Deaf Interpreter.

He has served on the Utah Interpreter Certification Advisory Board and Advisory Council for the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind from 2011 to 2013, representing the Utah Deaf community.

Jeff has a passion for snowboarding, skiing, skateboarding, wakeboarding, waterskiing, motorcycling, and other sports involving standing or sitting on something and going fast! He has competed in three Deaflympics (1999 Davos, Switzerland; 2003 Sundsvall, Sweden; and 2007 Salt Lake City, Utah) and would have competed in 2011 Vysoke, Slovakia, if they weren’t canceled. He is a certified snowboard coach.

He has served on the Utah Interpreter Certification Advisory Board and Advisory Council for the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind from 2011 to 2013, representing the Utah Deaf community.

Jeff has a passion for snowboarding, skiing, skateboarding, wakeboarding, waterskiing, motorcycling, and other sports involving standing or sitting on something and going fast! He has competed in three Deaflympics (1999 Davos, Switzerland; 2003 Sundsvall, Sweden; and 2007 Salt Lake City, Utah) and would have competed in 2011 Vysoke, Slovakia, if they weren’t canceled. He is a certified snowboard coach.