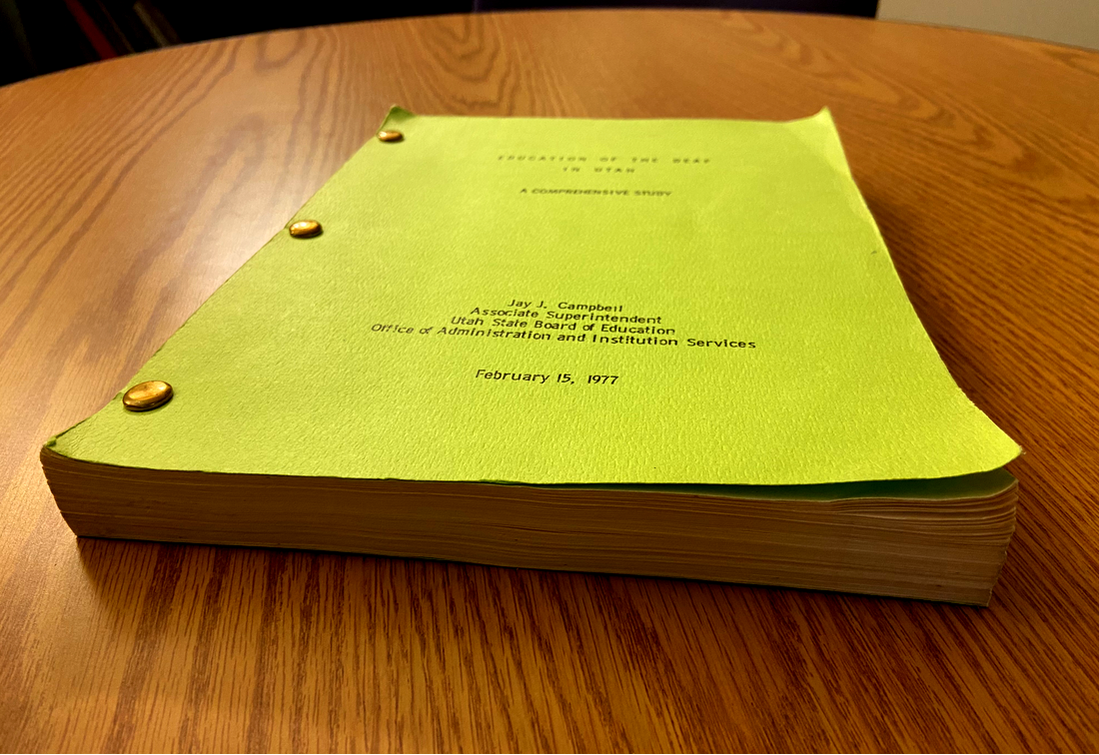

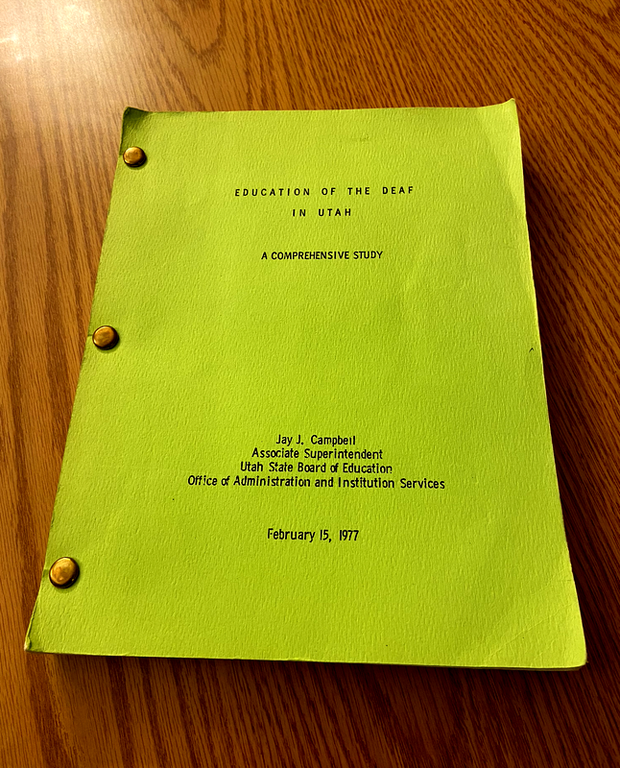

Dr. Jay J. Campbell's 1977

Comprehensive Study

of Deaf Education in Utah

Comprehensive Study

of Deaf Education in Utah

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Published in 2012

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

As a parent of two Deaf children, my passion for deaf education comes from my personal journey. My father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, also sparked my interest and shared with me the history of deaf education in Utah, including its oral and mainstreaming impact. This inspired me to meticulously document the controversial events of that era. If it weren't for him, I wouldn't be able to advocate for my kids without knowing the history. My studies at the Gallaudet School Social Work Program further deepened my understanding of the complexities of education, legislation, and policy. Moreover, my role on the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind has truly empowered me to advocate for my children and others in Utah who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled. This platform has given me the strength and voice to make a difference.

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Dr. Jay J. Campbell's

Comprehensive Study

Comes to Light

Comprehensive Study

Comes to Light

I want to express my gratitude to my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, a 1954 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf and father of two Deaf children, Deanne and Duane, for his pivotal role in sharing about Dr. Jay J. Campbell's crucial advocacy for the Utah Deaf community in 2006. Thirty years later, in 2007, Ken introduced me to Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study, which I found deeply intriguing, following its publication in 1977 for his Utah State Board of Education presentation. His study proposed critical recommendations for improving the relationship between the oral and sign language departments at the Utah School for the Deaf, which could have significantly benefited the school. Unfortunately, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a staunch oral and mainstream advocate at the Utah State Board of Education meeting, opposed Dr. Campbell's study, as detailed on this webpage.

Thank you, Ken, for sharing the history of deaf education in Utah with me and bringing Dr. Campbell's book out of dust. Without him, this history website would not have been possible. In addition to the two books by Dr. Campbell in their care, I'd like to thank my mother-in-law, Ilene Coles Kinner, for giving me the other book, which I had previously donated from Ken to the George Sutherland Archives at Utah Valley University for preservation.

Thank you, Ken and Ilene, for caring for Dr. Campbell's books and keeping them safe all these years!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Thank you, Ken and Ilene, for caring for Dr. Campbell's books and keeping them safe all these years!

Jodi Becker Kinner

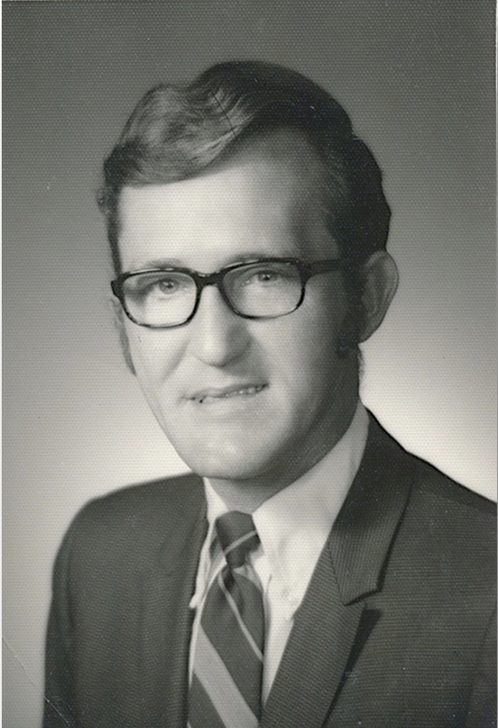

Acknowledgment

I, too, would like to express my gratitude to my colleague, Julie Hesterman Smith, an interpreter, who, through a family friend, had a connection with Dr. Jay J. Campbell, whom I was intrigued to meet. This connection allowed me to interview him and delve deeper into his study on July 1, 2007. Dr. Campbell's work had a profound impact on me, and meeting him and his wife, Beth Ann, who is a Child of Deaf Adults (CODA) and an interpreter, was a privilege. Dr. Campbell's legacy as a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community lives on, even after his passing on January 3, 2020, at the age of 96.

If you want to learn more about Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study, I invite you to explore this webpage. It offers a comprehensive overview of his critical research, which was the product of collaborative efforts between Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf leader in the Utah Deaf community, and other neutral researchers who worked closely with Dr. Campbell. Despite its prevention of implementation to strengthen the Utah School for the Deaf, I found it educational and fascinating, and I hope you will, too. Enjoy exploring the depths of Dr. Campbell's research!

Thank you so much, Julie, for introducing me to Dr. Campbell and his wife, Beth Ann!

Jodi Becker Kinner

If you want to learn more about Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study, I invite you to explore this webpage. It offers a comprehensive overview of his critical research, which was the product of collaborative efforts between Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf leader in the Utah Deaf community, and other neutral researchers who worked closely with Dr. Campbell. Despite its prevention of implementation to strengthen the Utah School for the Deaf, I found it educational and fascinating, and I hope you will, too. Enjoy exploring the depths of Dr. Campbell's research!

Thank you so much, Julie, for introducing me to Dr. Campbell and his wife, Beth Ann!

Jodi Becker Kinner

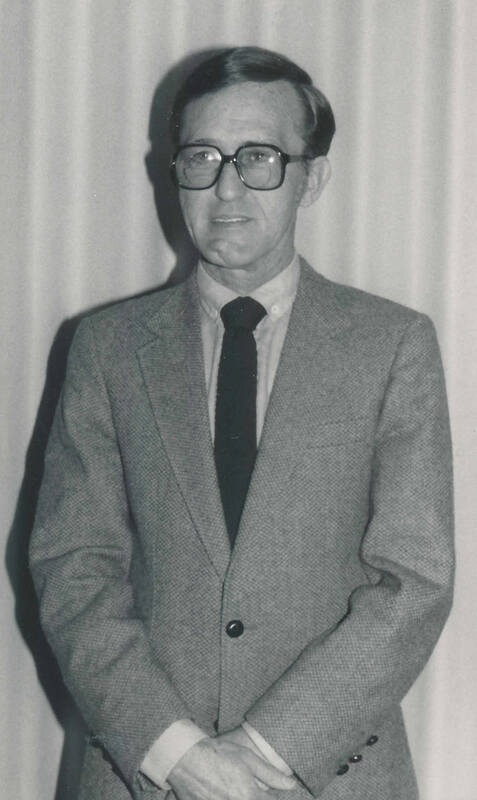

Like Ken and Julie, I would also like to thank Dr. Jay J. Campbell for his support and investment in the comprehension study, which was a crucial step in improving education and services at the Utah School for the Deaf. This initiative aimed to address the internal and external controversy surrounding the use of oral and sign language. Throughout deaf education history, there was a significant dispute between the Utah Association for the Deaf, led by Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent member of the Utah Deaf community and avid supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf, and Dr. Grant B. Bitter, who advocated for oral and mainstream education. Dr. Jay J. Campbell, husband of sign language interpreter Beth Ann Stewart Campbell and Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education at the time, played a unique and crucial role in this controversy. This conflict was a turning point in the history of deaf education, and Dr. Campbell, a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community, left an enduring impact.

Dr. Campbell passed away in 2020. I regret not recording his interview, during which he discussed his experience advocating for the Utah Deaf community, conducting a comprehensive study on deaf education, and overcoming obstacles with his opponent, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, and his oral advocates.

Thank you, Dr. Campbell, for your unwavering support and dedication to our community. Your contributions have been invaluable, and we are deeply grateful for all that you have done.

Jodi Becker Kinner

Dr. Campbell passed away in 2020. I regret not recording his interview, during which he discussed his experience advocating for the Utah Deaf community, conducting a comprehensive study on deaf education, and overcoming obstacles with his opponent, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, and his oral advocates.

Thank you, Dr. Campbell, for your unwavering support and dedication to our community. Your contributions have been invaluable, and we are deeply grateful for all that you have done.

Jodi Becker Kinner

Insightful Remarks from Beth Ann

Stewart Campbell Shed Light on her husband,

Dr. Jay J. Campbell's Research

Stewart Campbell Shed Light on her husband,

Dr. Jay J. Campbell's Research

Beth Ann Stewart Campbell shared a crucial insight at the interpreting workshop at Salt Lake Community College on October 15, 2010. Her husband, Dr. Jay J. Campbell, who was presented at the workshop, had conducted research on oral versus total communication in deaf education from 1975 to 1977. His findings, which supported total communication, showed great promise for improving deaf education. However, his research was reportedly concealed by the Utah State Board of Education and the Utah School for the Deaf, a missed opportunity to enhance deaf education in Utah. She also noted that I shed light on this issue and interviewed Dr. Campbell about his study in 2007. Beth Ann expressed surprise at the reemergence of this issue, highlighting the importance of raising awareness. She mentioned that there were tough times (Beth Ann Stewart Campbell Interview, YouTube, October 15, 2010). The following details the history of Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study and the obstacles that prevented it from enhancing deaf education in Utah.

We are very grateful to Beth Ann for her inspiring advocacy for the Utah Deaf community. Her experiences as an interpreter during the pre-Americans with Disabilities Act era, her firsthand experience with the deaf education battles during the Bitter/Sanderson era, and her continued advocacy were truly enlightening. During the interview, she mentioned the ongoing conflict between oral and sign language, but she believed it was not as vicious as it had been during the Bitter/Sanderson era. Unfortunately, I was unable to attend her workshop due to personal reasons. I want to express my heartfelt thanks to Julie Hesterman Smith, my co-worker, for making Beth Ann's presentation accessible to me.

Thank you, Beth Ann, for interpreting and advocating for our causes!

Jodi Becker Kinner

We are very grateful to Beth Ann for her inspiring advocacy for the Utah Deaf community. Her experiences as an interpreter during the pre-Americans with Disabilities Act era, her firsthand experience with the deaf education battles during the Bitter/Sanderson era, and her continued advocacy were truly enlightening. During the interview, she mentioned the ongoing conflict between oral and sign language, but she believed it was not as vicious as it had been during the Bitter/Sanderson era. Unfortunately, I was unable to attend her workshop due to personal reasons. I want to express my heartfelt thanks to Julie Hesterman Smith, my co-worker, for making Beth Ann's presentation accessible to me.

Thank you, Beth Ann, for interpreting and advocating for our causes!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Did You Know?

Norman Williams, a 1962 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf and father of two Deaf daughters, Penny and Jan, remembers finding Dr. Campbell's Comprehensive Study in the trash can at the Utah State Office of Education a few years after the fateful presentation. He had heard a lot about this research and was overjoyed to finally have the book in his hands (Norman Williams, personal communication, January 20, 1010). Kenneth L. Kinner and Norman Williams deserve credit for keeping Dr. Jay J. Campbell's book safe for all these years.

Kenneth L. Kinner and Norman Williams deserve credit for keeping Dr. Jay J. Campbell's book safe for all these years.

Kenneth L. Kinner and Norman Williams deserve credit for keeping Dr. Jay J. Campbell's book safe for all these years.

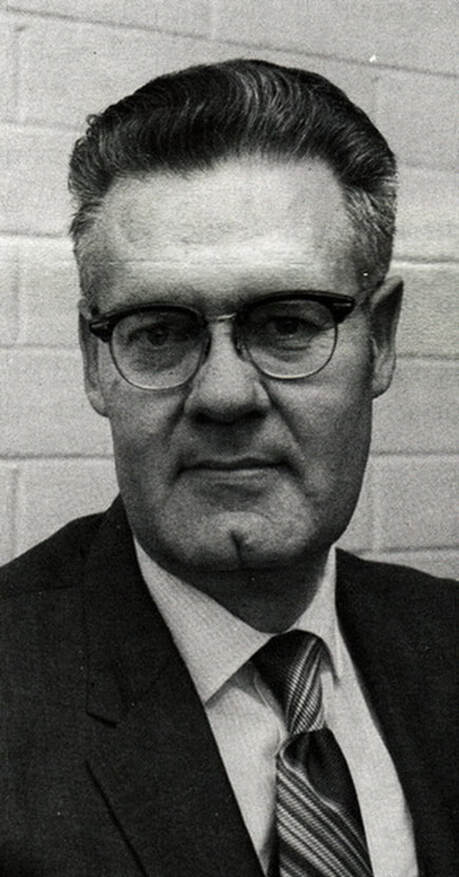

Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

the Father of Mainstreaming

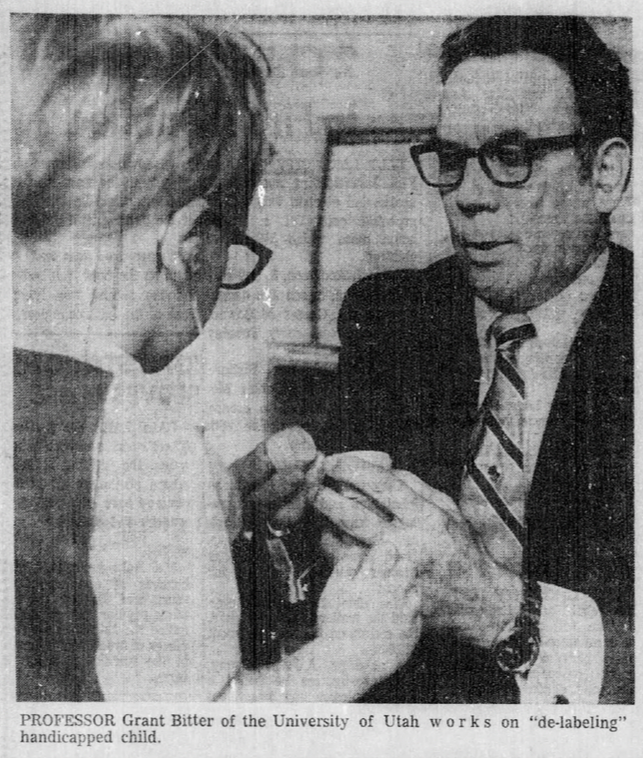

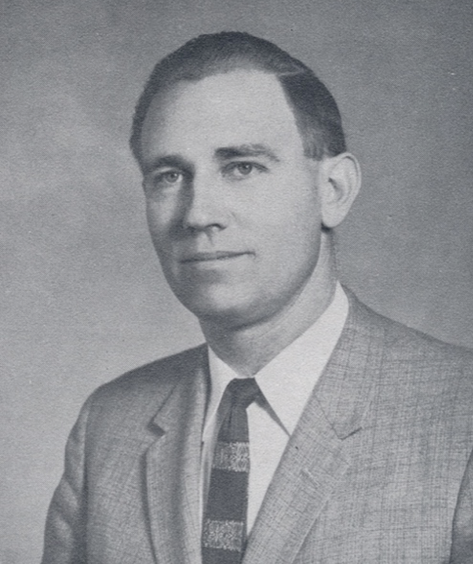

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter, who opposed anyone who stood in the way of his goals of promoting oral and mainstream education, has formally requested the job removal of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, both respected advocates for sign language. He believed they were interfering with his mission. Additionally, he expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, feeling it did not align with his educational goals. He also asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected committee chairperson, to resign because she invited representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he saw as a shift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf, in the face of Dr. Bitter's opposition, demonstrated remarkable resilience, marking a significant turning point in their history and inspiring others with their strength and determination.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. His journey began at the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked as a teacher and curriculum coordinator. His passion for education led him to become a director and professor in the Teacher Training Program, where he focused primarily on oral education under the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. Dr. Bitter also served as the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

The Implementation of the Dual-Track Program,

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

In the fall of 1962, the Utah Deaf community was surprised by the revolutionary changes at the Utah School for the Deaf, which introduced the dual-track program, also commonly known as the "Y" system. The unexpected change had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children, evoking a sense of empathy within the community. The Utah Association of the Deaf, which advocated for sign language, was unaware that the Utah Council for the Deaf had spearheaded the change, advocating for speech-based instruction and successfully pushing for its implementation at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962). It is believed that Dr. Bitter was a member of this council. The dual-track program provided an oral program in one department and a simultaneous communication program in another department, which was later replaced by a combined system. However, the dual-track policy mandated that all Deaf children begin with the oral program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Gannon, 1981). The Utah State Board of Education, a key player in educational policy, approved this policy reform on June 14, 1962, with endorsement from the Special Study Committee on Deaf Education (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). The newly hired superintendent, Robert W. Tegeder, accepted the parents' proposals and initiated changes to the school system (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter, 1962; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). This new program not only affected the lives of Deaf children but also their families.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

As a result of the "Y" system's implementation, the Utah School for the Deaf had to undergo significant changes. The school had to hire more oral teachers and establish speech as the primary mode of communication, shifting the focus of the learning environment. The dual-track program initially placed all elementary school students in the oral department, transferring them to the simultaneous communication department only if they failed in the oral program. This approach was based on the belief that early development of oral skills was crucial for Deaf students, with sign language learning considered a secondary focus. The change in focus and the increased hiring of oral teachers had a significant impact on the school's learning environment, altering its dynamics and atmosphere (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, some changes were made at the Utah School for the Deaf without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were surprised to find out about the changes. These changes caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The Implementation

of the The Two-Track Program

at the Utah School for the Deaf

of the The Two-Track Program

at the Utah School for the Deaf

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy.

Following the 1962 protest against social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a steadfast advocate for oral and mainstream education, and his oral supporters suspected that the Utah Association of the Deaf had organized the student strike. The Utah State Board of Education conducted an investigation but found no evidence of any connection between the students and the Utah Association for the Deaf (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). In the face of societal segregation, the simultaneous communication students demonstrated their unwavering determination and courage by staging their own protests.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

Another round of students' acts of resistance during the 1969 walkout protest against the continued enforcement of "Y" social segregation in the dual-track program was a defining moment in history, echoing the 1962 student protest at the Utah School for the Deaf. Despite not achieving the desired results, they found new ways to voice their discontent. Some sign language students boldly crossed the oral department hallway, while others took the simultaneous communication department route. This act of defiance broke the "Y" system rule, which had designated these spaces as 'off-limits' in order to maintain a 'clean' communication environment. Students even confronted their oral teachers, accusing them of oppression and dominance (Raymond Monson, personal communication, November 9, 2010). For nearly a decade, the Utah Association for the Deaf, in collaboration with the Parent-Teacher-Student Association, comprised supportive parents who advocated for sign language and fought against the "Y" system. Despite years of dismissal and opposition, their unwavering determination and resilience in the face of social segregation are truly admirable.

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, when faced with a challenging situation, sought assistance from his boss, Dr. Jay J. Campbell. Dr. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Campbell, a sign language interpreter and the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, had been a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community. Motivated by his concern for the welfare of Deaf children, he took the initiative to create the two-track program, a new instrument system that replaced the "Y" system (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Campbell, 1977; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). His dedication and commitment to the cause are genuinely inspiring.

Ned C. Wheeler, who became deaf at the age of 13 and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1933, was the chair of the USDB Governor's Advisory Council. He proposed the "two-track program" in response to various events, including Dr. Campbell's proposal, student strikes in 1962 and 1969, and opposition from the Parent Teacher Student Association to the "Y" system policy. On December 28, 1970, the Utah State Board of Education authorized a new policy, paving the way for the Utah School for the Deaf to operate a two-track program with choices, eliminating the "Y" system. This program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011, Recommendations on Policy for the Utah School for the Deaf, 1970; Deseret News, December 29, 1970).

Following the 1962 protest against social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a steadfast advocate for oral and mainstream education, and his oral supporters suspected that the Utah Association of the Deaf had organized the student strike. The Utah State Board of Education conducted an investigation but found no evidence of any connection between the students and the Utah Association for the Deaf (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). In the face of societal segregation, the simultaneous communication students demonstrated their unwavering determination and courage by staging their own protests.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

Another round of students' acts of resistance during the 1969 walkout protest against the continued enforcement of "Y" social segregation in the dual-track program was a defining moment in history, echoing the 1962 student protest at the Utah School for the Deaf. Despite not achieving the desired results, they found new ways to voice their discontent. Some sign language students boldly crossed the oral department hallway, while others took the simultaneous communication department route. This act of defiance broke the "Y" system rule, which had designated these spaces as 'off-limits' in order to maintain a 'clean' communication environment. Students even confronted their oral teachers, accusing them of oppression and dominance (Raymond Monson, personal communication, November 9, 2010). For nearly a decade, the Utah Association for the Deaf, in collaboration with the Parent-Teacher-Student Association, comprised supportive parents who advocated for sign language and fought against the "Y" system. Despite years of dismissal and opposition, their unwavering determination and resilience in the face of social segregation are truly admirable.

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, when faced with a challenging situation, sought assistance from his boss, Dr. Jay J. Campbell. Dr. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Campbell, a sign language interpreter and the Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, had been a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community. Motivated by his concern for the welfare of Deaf children, he took the initiative to create the two-track program, a new instrument system that replaced the "Y" system (First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni, 1976; Campbell, 1977; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). His dedication and commitment to the cause are genuinely inspiring.

Ned C. Wheeler, who became deaf at the age of 13 and graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1933, was the chair of the USDB Governor's Advisory Council. He proposed the "two-track program" in response to various events, including Dr. Campbell's proposal, student strikes in 1962 and 1969, and opposition from the Parent Teacher Student Association to the "Y" system policy. On December 28, 1970, the Utah State Board of Education authorized a new policy, paving the way for the Utah School for the Deaf to operate a two-track program with choices, eliminating the "Y" system. This program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011, Recommendations on Policy for the Utah School for the Deaf, 1970; Deseret News, December 29, 1970).

However, while supervising the Utah School for the Deaf, Dr. Campbell noticed that parents were often unaware of their children's educational and communication options (Campbell, 1977). Despite the Utah State Board of Education releasing policies in 1970, 1977, and 1998, the Utah School for the Deaf's Communication Guidelines did not provide parents with a wide range of choices. This lack of clarity resulted in ineffective placement tactics due to the prevalent oral bias.

Dr. Jay J. Campbell Shares his

Comprehensive Study

on the Education of the Deaf in Utah

Comprehensive Study

on the Education of the Deaf in Utah

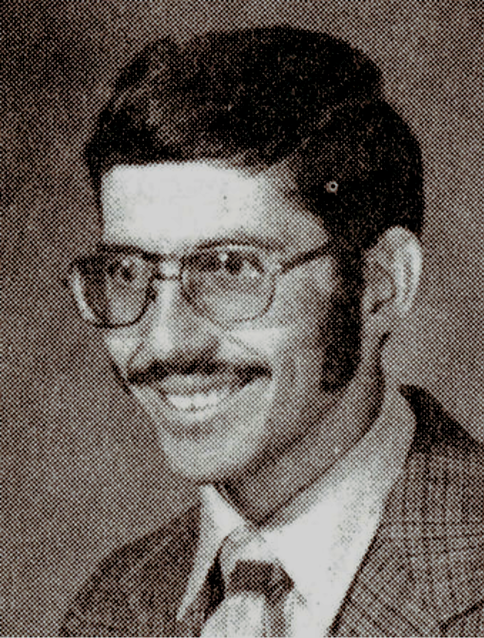

In 1966, the Utah State Office of Education appointed Dr. Jay J. Campbell, a respected individual and advocate for the Utah Deaf community, to oversee the Utah School for the Deaf. During his tenure from 1966 to 1977, he witnessed the ongoing controversy between Dr. Bitter, who advocated for oral communication, and Dr. Sanderson, who supported sign language. Furthermore, Dr. Campbell observed a conflict between the Oral Program and the Total Communication Program on communication methods, both within and outside the Utah School for the Deaf. In 1975, the Utah State Board of Education approved Dr. Campbell's investigation project on deaf education in Utah, which was a crucial step in improving education and services at the Utah School for the Deaf (Campbell, 1977; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2006; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

Dr. Campbell's study, a significant contribution to the field of deaf education, focused on bridging the educational training gap between the Utah School for the Deaf and the school districts. It aimed to improve the resources available to Deaf and hard of hearing children and develop a comprehensive and inclusive education system for these students. The study's major areas of focus were:

Dr. Campbell's study, a significant contribution to the field of deaf education, focused on bridging the educational training gap between the Utah School for the Deaf and the school districts. It aimed to improve the resources available to Deaf and hard of hearing children and develop a comprehensive and inclusive education system for these students. The study's major areas of focus were:

- An analysis of research on communication methods used in educating the deaf,

- A study of deaf children in Utah school districts,

- A sample of opinions of parents of older students at the Utah School for the Deaf,

- Comments from professional staff,

- Letters/materials received from national leaders and educators of the deaf,

- Perceptions and recommendations from former USD students,

- Professional interpreters for the deaf, and

- Professional counselors for the deaf.

After an extensive two-year study period, Dr. Campbell, in collaboration with external researchers, presented his comprehensive report on February 15, 1977. This study, spanning from 1960 to 1977, included students from both mainstream school districts and the Utah School for the Deaf. The report aimed to settle the ongoing debate between oral and total communication, address the internal conflicts at the Utah School for the Deaf, and provide policy proposals for the Utah State Board of Education to consider (Campbell, 1977).

The report showed that students' poor academic performance was due to conflicts between two educational ideologies. Unfortunately, this debate overlooked the education and language needs of Deaf children. Other issues included a shortage of teacher aides and tutors at the Utah School for the Deaf, and teachers felt overwhelmed by educating children of varying ages, language skills, and cognitive abilities in one classroom. One teacher pointed out that there was a significant difference in ability levels between students in most classes, and sometimes, a teacher had to teach at different levels at the same time. However, a capable assistant could help the teacher by conducting specific instructional activities with a group of students while the teacher instructs the rest. Utilizing assistants can increase the amount of language input each student receives throughout the day and maximize instructional time for teaching students (Campbell, 1977, p. 78).

Dr. Campbell's investigation also revealed that many Deaf students were unprepared for work and lacked the basic skills required to function in mainstream society. Furthermore, the larger number of students with additional disabilities had a detrimental effect on the Utah School for the Deaf's ability to deliver quality education over the seventeen years of study. Many school districts lacked the administrative commitment and skilled employees necessary to educate the Deaf successfully. Interactions between deaf and hearing students were relatively limited in the mainstream setting. According to Dr. Campbell's study, Deaf students were happier and more socially adjusted when they had other deaf students to associate with (Campbell, 1977).

Dr. Campbell's investigation also revealed that many Deaf students were unprepared for work and lacked the basic skills required to function in mainstream society. Furthermore, the larger number of students with additional disabilities had a detrimental effect on the Utah School for the Deaf's ability to deliver quality education over the seventeen years of study. Many school districts lacked the administrative commitment and skilled employees necessary to educate the Deaf successfully. Interactions between deaf and hearing students were relatively limited in the mainstream setting. According to Dr. Campbell's study, Deaf students were happier and more socially adjusted when they had other deaf students to associate with (Campbell, 1977).

Observation of a Two-Track System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Dr. Campbell conducted a study on the two-track program and the conflict it caused at the Utah School for the Deaf. The study included a letter from a respondent, which contained important observations and suggestions. Based on observations and suggestions in the letter, Dr. Campbell proposed a 'two-track system' in separate schools to solve internal and external conflicts, eliminate competition, and alleviate tensions between the two programs. He recommended that each program have its own dean, supervisor, principal, teachers, and students to avoid competition and tensions between the two programs. At the time, two oral and sign language coordinators reported to the principal, who favored oral education. This has had a negative impact on the sign language department, prompting a request to the Utah State Board of Education for the separation of two schools. The letter in the following section provides a better understanding of the challenges surrounding the dual-track program.

A Letter Detailing the Impact of the Dual-Track Program

“After observing the “two track system” as used by the Utah School for the Deaf, I believe its operation offers Utah the greatest flexibility in individualization and yet its operation creates intense in-house and in-state strife that significantly impairs the effectiveness of the school.

I believe that a state that offers only one communicative system for all deaf children is denying children the MOST important educational alternative that a deaf child needs. There is no question that there is a loss of potential and a great deal of inappropriate placement of deaf children when only one communicative system is offered. I would strongly support the continuation of a two-track system if the internal and external strife can be eliminated. However, at this point, I believe the strife has reached catastrophic stages and the whole education process is endangered.

I would like to first point out what I feel to be the source of this strife, then the results of the strife, and lastly, some suggestions for dealing with the problem.

I believe the source of the strife is in two completely separate programs. Each program has its own dean, its own supervisor, its own teachers, students, parents and, of course, supporters and enemies.

Strife is inherent in such program division. Each program is threatened by the other and when a person is threatened, he fights and attempts to put down the source of the threat. For example, the entrance of a new child into the school has become a battleground for the two programs. The competition is fierce, and children and parents are solicited by each program. Movement from one program to another is very difficult because of the competition. If children are transferred from one program to another, it reduces the number of students a teacher has and often threatens the [teacher’s job] because there are no longer enough students. Children and parents are seen as vehicles to support a program. Thus, I would suggest that the two-track system is not providing the individualization it was created to do and at the same time it is creating strife. I have sensed a great deal of mistrust and suspicion among the staff of the school supervisors and administration.

The strife and competition generated among staff is spread to the parents. The parents soon “join one camp or the other,” become strong advocates of a method, and then try to “win converts to their cause.” We have found parents of children in the PIP [Parent-Infant Program] that are already so biased, they cannot accept communicative and educational recommendations from the PIP staff.

…..There must be structure which allows for a fluid system permitting the movement of children and staff to maximize the education for each child. I believe the school must hire educators of the deaf not oralists or manualists. These teachers should be able to teach all deaf children in their particular area of expertise, not total communication or oral. I believe the teachers and supervisors must be concerned with children not with methods. The method should be used only as educational (communicative) alternatives.

I realize this would be very difficult to achieve but I believe it must be done or TWO separate schools established. If the state establishes two separate schools for the deaf, they will eliminate the in-house strife, but the external strife will be escalated and the competition for children will become even greater. I believe the state should do everything possible to develop a functional two option communicative program. I believe the ‘two school’ notion would create more problems than it would solve.

I would suggest the place to begin is to change the current infant, pre-school, and 1st/2ndgrade programs into an “Early Childhood Program” with one person over the whole program. The teachers would work with either “TC” or “Oral” children or both. Those teachers who could not do this could be moved to another level. Children in the Early Childhood Program would not be placed in an “oral” or “total” program but would receive whatever training is recommended and appropriate. By the time a child leaves the Early Childhood Program, a complete communicative evaluation could have been completed and he could then be placed in a “total communication track” or “oral track.” As this system develops and becomes functional, it could be slowly moved to the other areas of the school.

I realize I am suggesting you open a huge “can of worms.” This would take a great deal of planning and commitment to implement” (p. 82-83).

I believe that a state that offers only one communicative system for all deaf children is denying children the MOST important educational alternative that a deaf child needs. There is no question that there is a loss of potential and a great deal of inappropriate placement of deaf children when only one communicative system is offered. I would strongly support the continuation of a two-track system if the internal and external strife can be eliminated. However, at this point, I believe the strife has reached catastrophic stages and the whole education process is endangered.

I would like to first point out what I feel to be the source of this strife, then the results of the strife, and lastly, some suggestions for dealing with the problem.

I believe the source of the strife is in two completely separate programs. Each program has its own dean, its own supervisor, its own teachers, students, parents and, of course, supporters and enemies.

Strife is inherent in such program division. Each program is threatened by the other and when a person is threatened, he fights and attempts to put down the source of the threat. For example, the entrance of a new child into the school has become a battleground for the two programs. The competition is fierce, and children and parents are solicited by each program. Movement from one program to another is very difficult because of the competition. If children are transferred from one program to another, it reduces the number of students a teacher has and often threatens the [teacher’s job] because there are no longer enough students. Children and parents are seen as vehicles to support a program. Thus, I would suggest that the two-track system is not providing the individualization it was created to do and at the same time it is creating strife. I have sensed a great deal of mistrust and suspicion among the staff of the school supervisors and administration.

The strife and competition generated among staff is spread to the parents. The parents soon “join one camp or the other,” become strong advocates of a method, and then try to “win converts to their cause.” We have found parents of children in the PIP [Parent-Infant Program] that are already so biased, they cannot accept communicative and educational recommendations from the PIP staff.

…..There must be structure which allows for a fluid system permitting the movement of children and staff to maximize the education for each child. I believe the school must hire educators of the deaf not oralists or manualists. These teachers should be able to teach all deaf children in their particular area of expertise, not total communication or oral. I believe the teachers and supervisors must be concerned with children not with methods. The method should be used only as educational (communicative) alternatives.

I realize this would be very difficult to achieve but I believe it must be done or TWO separate schools established. If the state establishes two separate schools for the deaf, they will eliminate the in-house strife, but the external strife will be escalated and the competition for children will become even greater. I believe the state should do everything possible to develop a functional two option communicative program. I believe the ‘two school’ notion would create more problems than it would solve.

I would suggest the place to begin is to change the current infant, pre-school, and 1st/2ndgrade programs into an “Early Childhood Program” with one person over the whole program. The teachers would work with either “TC” or “Oral” children or both. Those teachers who could not do this could be moved to another level. Children in the Early Childhood Program would not be placed in an “oral” or “total” program but would receive whatever training is recommended and appropriate. By the time a child leaves the Early Childhood Program, a complete communicative evaluation could have been completed and he could then be placed in a “total communication track” or “oral track.” As this system develops and becomes functional, it could be slowly moved to the other areas of the school.

I realize I am suggesting you open a huge “can of worms.” This would take a great deal of planning and commitment to implement” (p. 82-83).

As part of a study, the Utah State Office of Education assigned Dr. Robert G. Sanderson to conduct a survey of the alums of the Utah School for the Deaf to confirm their experience regarding the education they received there. The survey compared the opinions of graduates who completed their studies at the school before 1948, those who graduated between 1948 and 1959, and those who graduated between 1960 and 1977. The results revealed a significant difference in the alums' views. Graduates who completed their studies before 1949 had a more positive experience at the school; they understood their teachers better and enjoyed the administrators more than those who graduated between 1960 and 1977. The results for the students who graduated between 1949 and 1959 fell between the two categories (Sanderson, 1977).

Based on the research, Dr. Campbell developed these recommendations as follows:

Based on the research, Dr. Campbell developed these recommendations as follows:

- Restructure and strengthen the programs to reduce the competition and tension and meet the children’s educational needs through a fair placement process,

- Improve the evaluation of each student in relation to communication methods used in educating the deaf,

- Provide periodic evaluations of all students and, if needed, recommendations for transfer,

- Provide aid and education to parents as they make decisions regarding placement,

- Set up an early intervention program for deaf toddlers and preschoolers,

- Improve curriculum and offer vocational courses for skill-building targeted to obtain employment,

- Encourage teachers and parents to become involved with the deaf community and have the right attitude towards the deaf,

- Include the state evaluative process for deaf children in school districts under the direction of USD and make recommendation along the spectrum of placements,

- Keep up with the research on services and education trends,

- Coordinate the educational research of USD with research from other states, and

- Reconsider and rewrite USD policies to clarify their intent and ensure that they reflect a coherent and consistent policy (Campbell, 1977).

Education of Deaf Stirs Debate:

No Educational Action Taken

No Educational Action Taken

In the past three months, from February to April 1977, the Utah State Board of Education has been listening to heated debate on appropriate methods for deaf education. Speakers have been passionately arguing over proposals to separate the two programs at the Utah School for the Deaf (Peters, Deseret News, April 15, 1977). Caught between oral and total communication conflicts, the Utah State Board of Education wanted to focus on strengthening both programs rather than their disputes (Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 15, 1977).

On April 14, 1977, Dr. Campbell presented his 200-page comprehensive study report to the Utah State Board of Education at the Utah School for the Deaf. He shared his findings and recommendations for improving education at the Utah School for the Deaf, advocating for more equitable evaluation and placement systems (Campbell, 1977). His report was a significant contribution to addressing the ongoing debate over deaf education. However, Dr. Bitter, a professor at the University of Utah, strongly opposed Dr. Campbell's research, as it indicated that Deaf children excel academically in sign language. Dr. Bitter, a defender of oral and mainstream education, expressed his opposition to the Utah State Board of Education in the presence of more than 300 parents of orally Deaf children who supported his views. He also scolded both oral and total communication groups for their ongoing debates over the most effective approach and challenged them to work together to enhance the quality of deaf education (Peters, Deseret News, April 15, 1977). Dr. Bitter stressed the importance of providing parents with options for their children and preserving their rights to make decisions concerning their children's education (Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 15, 1977). He also spoke against Dr. Campbell's research, stating that it contained falsehoods and unfounded conclusions about the Teacher Oral Training Program at the University of Utah and educational programs across the state (G.B. Bitter, personal communication, March 6, 1978). While Dr. Bitter may advocate for dual options, the reality is that the oral program was the initial choice for parents and Deaf children. Dr. Campbell, Dr. Sanderson, and the Utah Association for the Deaf, who have witnessed the harsh realities of Deaf students failing the oral program and transitioning to the total communication program, illuminate this stark contrast. They have encountered numerous parents who were unaware of alternative options, such as total communication, when they were advised to enroll their Deaf child in the oral program. Dr. Campbell's deep-seated dedication to finding solutions that would benefit both groups spurred him to embark on a research journey.

On April 14, 1977, Dr. Campbell presented his 200-page comprehensive study report to the Utah State Board of Education at the Utah School for the Deaf. He shared his findings and recommendations for improving education at the Utah School for the Deaf, advocating for more equitable evaluation and placement systems (Campbell, 1977). His report was a significant contribution to addressing the ongoing debate over deaf education. However, Dr. Bitter, a professor at the University of Utah, strongly opposed Dr. Campbell's research, as it indicated that Deaf children excel academically in sign language. Dr. Bitter, a defender of oral and mainstream education, expressed his opposition to the Utah State Board of Education in the presence of more than 300 parents of orally Deaf children who supported his views. He also scolded both oral and total communication groups for their ongoing debates over the most effective approach and challenged them to work together to enhance the quality of deaf education (Peters, Deseret News, April 15, 1977). Dr. Bitter stressed the importance of providing parents with options for their children and preserving their rights to make decisions concerning their children's education (Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 15, 1977). He also spoke against Dr. Campbell's research, stating that it contained falsehoods and unfounded conclusions about the Teacher Oral Training Program at the University of Utah and educational programs across the state (G.B. Bitter, personal communication, March 6, 1978). While Dr. Bitter may advocate for dual options, the reality is that the oral program was the initial choice for parents and Deaf children. Dr. Campbell, Dr. Sanderson, and the Utah Association for the Deaf, who have witnessed the harsh realities of Deaf students failing the oral program and transitioning to the total communication program, illuminate this stark contrast. They have encountered numerous parents who were unaware of alternative options, such as total communication, when they were advised to enroll their Deaf child in the oral program. Dr. Campbell's deep-seated dedication to finding solutions that would benefit both groups spurred him to embark on a research journey.

Dr. Bitter heavily criticized his adversary, Dr. Sanderson's survey of the Utah School for the Deaf alums, which was presented to the Utah State Board of Education. He raised concerns about the validity and reliability of Dr. Sanderson's population and sample procedures, which caused a lot of confusion. Some people alleged that Dr. Sanderson supported the creation of two separate schools for the two educational approaches while maintaining the Total Communication Department on Ogden's residential campus. Others argued that the previous reports showed that the Ogden campus's orientation program for parents of new students was biased in favor of the oral approach (Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, April 15, 1977). In this regard, Dr. Bitter requested the State Board postpone action on Dr. Campbell's report and recommendations (G.B. Bitter, personal communication, April 14, 1977).

During his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter stated that he and the school administration challenged Dr. Campbell and Dr. Sanderson, who were members of the committee studying the Utah School for the Deaf. Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, under Dr. Campbell's supervision, had to exercise caution (Grant Bitter, Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). It appeared that Superintendent Tegeder became caught up in the conflict between Bitter and Campbell-Sanderson, and he also had to exercise caution to avoid jeopardizing his job as the school administrators supported Bitter.

During his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter stated that he and the school administration challenged Dr. Campbell and Dr. Sanderson, who were members of the committee studying the Utah School for the Deaf. Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder, under Dr. Campbell's supervision, had to exercise caution (Grant Bitter, Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). It appeared that Superintendent Tegeder became caught up in the conflict between Bitter and Campbell-Sanderson, and he also had to exercise caution to avoid jeopardizing his job as the school administrators supported Bitter.

During a board meeting, Peter Vlahos, an Ogden-based lawyer and a parent of a Deaf daughter, presented a compelling argument. He stated that Utah is fortunate to have both methods of education available to Deaf children, but it was unfortunate that they were almost always in conflict. He added that he was proud of his daughter's accomplishments and questioned why proving one approach was better than the other should take precedence over educating children. Peter also mentioned that two-thirds of Deaf schoolchildren's parents requested the removal of Dr. Campbell and Dr. Sanderson from their roles over oral students. The presentation was heated, with over 300 parents supporting the oral method and cheering Dr. Bitter and Peter Viahos as they presented their arguments (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977).

A group of parents, under the influence of Dr. Bitter, petitioned the Utah State Board of Education to suspend Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study, citing its inconclusive nature. Also, dissatisfied with his research findings, they demanded his termination (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2006; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). Approximately 50 to 60 Deaf individuals attended the meeting (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Those attendees were Ned C. Wheeler, W. David Mortensen, Lloyd Perkins, Dennis Platt, Kenneth L. Kinner, and others.

Dr. Bitter, a spokesperson for the oral advocates, presented Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, with three options:

Dr. Talbot's response to Dr. Bitter's appeal sparked a firestorm of tension. The Deaf group fiercely opposed the State Board's decision to reassign Dr. Campbell within the Utah State Office of Education. Their dissatisfaction was intense, leading them to express their protest by stomping their feet on the floor. In his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter described the scene as highly emotional and wild, prompting him to consider leaving the room. Concerned about the escalating situation, Dr. Talbot asked the Deaf community members to leave the room (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Disagreements still exist about what the Deaf people did during the meeting, as different versions of what happened differ.

The Utah State Board of Education accepted Dr. Campbell's report and supporting documentation. However, despite the controversy surrounding his analysis, which included data from independent researchers, they disregarded all of his recommendations (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977). This decision had consequences, as Dr. Campbell's plan crumbled down, including a two-year study to improve education through fair assessment and placement procedures. His plan was buried and forgotten (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2006; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

A group of parents, under the influence of Dr. Bitter, petitioned the Utah State Board of Education to suspend Dr. Campbell's comprehensive study, citing its inconclusive nature. Also, dissatisfied with his research findings, they demanded his termination (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2006; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007). Approximately 50 to 60 Deaf individuals attended the meeting (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Those attendees were Ned C. Wheeler, W. David Mortensen, Lloyd Perkins, Dennis Platt, Kenneth L. Kinner, and others.

Dr. Bitter, a spokesperson for the oral advocates, presented Dr. Campbell's boss, Dr. Walter D. Talbot, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, with three options:

- Removing Dr. Campbell from his position;

- Assigning him to another position; or

- Requesting a grand jury investigation into the evidence demonstrating how oral Deaf individuals were intimidated by some of the state's programs (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

Dr. Talbot's response to Dr. Bitter's appeal sparked a firestorm of tension. The Deaf group fiercely opposed the State Board's decision to reassign Dr. Campbell within the Utah State Office of Education. Their dissatisfaction was intense, leading them to express their protest by stomping their feet on the floor. In his 1987 interview with the University of Utah, Dr. Bitter described the scene as highly emotional and wild, prompting him to consider leaving the room. Concerned about the escalating situation, Dr. Talbot asked the Deaf community members to leave the room (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). Disagreements still exist about what the Deaf people did during the meeting, as different versions of what happened differ.

The Utah State Board of Education accepted Dr. Campbell's report and supporting documentation. However, despite the controversy surrounding his analysis, which included data from independent researchers, they disregarded all of his recommendations (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 15, 1977). This decision had consequences, as Dr. Campbell's plan crumbled down, including a two-year study to improve education through fair assessment and placement procedures. His plan was buried and forgotten (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, 2006; Dr. Jay J. Campbell, personal communication, July 1, 2007).

A New Parent Infant Program

Orientation is Formed

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Orientation is Formed

at the Utah School for the Deaf

The mental trend of the "Y" system in the two-track program, with prevalent oral bias, persisted. This biased information had a profound impact, limiting the choices parents could make for their Deaf children's education and communication. Although Dr. J. Jay Campbell tried to provide fair information in the 1970s, Dr. Bitter opposed his efforts because he believed that total communication was a concept, not a word, and also a philosophy, not a method (Campbell, 1977; Cummins, The Salt Lake Tribune, August 20, 1977, p. 25; Bitter, Concern with Deaf Center Paper, 1985). In 2010, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group challenged this biased approach and advocated for unbiased and equal information. Superintendent Steven W. Noyce of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, an oral advocate and former university student of Dr. Bitter, as well as a long-time teacher and school director, created the Parent Infant Program Orientation to provide parents with fair and balanced information. However, parents still had to choose an "either/or" selection between ASL/English bilingual (replaced total communication) or listening and spoken language (replace oral) options for their children's education and communication, which resulted in the expansion of the listening and spoken program because the majority of Deaf children are born to hearing parents.

Jeff W. Pollock, a member of the USDB Advisory Council representing the Utah Deaf community, requested on February 10, 2011, that the Utah School for the Deaf implement the guidelines titled "The National Agenda: Moving Forward on Achieving Educational Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students" to address philosophical, placement, communication, and service delivery biases. One of the members of the Advisory Council wondered if the Deaf National Agenda was solely based on ASL. He clarified that the Deaf National Agenda does not exclusively rely on ASL but instead emphasizes the holistic development of each child, supporting both ASL and spoken language, unlike the current system's "either/or" approach. Jeff then addressed Superintendent Noyce in the eyes and stated that the USD has reverted to the inefficient "Y" system of the last 30–40 years, with an oral OR sign, and is not providing both ASL and LSL to parents who want both options. Superintendent Noyce remained silent about the subject. The "Y" system mental trend in the two-track program with prevalent oral bias persisted until Joel Coleman, superintendent of Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind, and Michelle Tanner, associate superintendent of Utah Schools for the Deaf, took action. Creating the Hybrid Program in 2016 was a significant step towards removing the requirement for parents to choose between the two programs "either/or." Their innovative approach is crucial and brings hope for unbiased and equal information. More information about the hybrid program can be found at the end of this webpage.

Suffice it to say, Dr. Grant B. Bitter was a prominent figure in Utah's oralism and mainstreaming movement, which had a significant impact on deaf education in Utah since 1962, despite the new Two-Track Program and the school's option guidelines. As a result of his efforts, the number of students attending Ogden's residential school for Deaf students decreased, and the quality of education also declined. The mainstreaming approach gained popularity but left many alums heartbroken. Dr. Bitter also had significant power as a parental figure and used it to push for oralism, making it difficult for the Utah Association for the Deaf to challenge him. When the Teacher Training Program in the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah closed in 1986, he retired in 1987 (Bitter, A Summary Report for Tenure, March 15, 1985). Today, the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah offers a Specialization in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program. While the curriculum does include American Sign Language classes, it still places a greater emphasis on Listening and Spoken Language. This reflects the impact that Dr. Bitter, who passed away in 2000, continues to have on deaf education in Utah. To learn more about the evolving mainstreaming movement, visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective' webpage.

The Parent Teacher Association

of the Utah School for the Deaf is Divided Over Communication Philosophy

of the Utah School for the Deaf is Divided Over Communication Philosophy

Before I delve into the debate between the advocates of oral and total communication at the Utah State Board of Education in the section at the end of the webpage, I'd like to provide some context regarding an earlier dispute in the PTA meetings, which Dr. Jay J. Campbell witnessed. The disagreement eventually led to a proposal to create separate campuses for oral and total communication at the state board meetings, which was not implemented primarily due to the strong opposition from Dr. Grant B. Bitter and his influential oral advocates.

Controversy at the

Parent Teacher Association Functions

Parent Teacher Association Functions