Students Strike Over the Oral

and Sign Language Segregation Policy

at the Utah School for the Deaf

in 1962 and 1969

and Sign Language Segregation Policy

at the Utah School for the Deaf

in 1962 and 1969

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

As a parent of two Deaf children, my passion for deaf education comes from my personal journey. My father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, also sparked my interest and shared with me the history of deaf education in Utah, including its oral and mainstreaming impact. This inspired me to meticulously document the controversial events of that era. If it weren't for him, I wouldn't be able to advocate for my kids without knowing the history. My studies at the Gallaudet School Social Work Program further deepened my understanding of the complexities of education, legislation, and policy. Moreover, my role on the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind has truly empowered me to advocate for my children and others in Utah who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled. This platform has given me the strength and voice to make a difference.

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Acknowledgment

I wanted to thank my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, for sharing about the dual-track and two-track programs at the Utah School for the Deaf, as well as the impact of the "Y" system. As the father of two Deaf children, Deanne and Duane, his first-hand experience within the system was a valuable source of information. Because I was so fascinated by those segregation programs at Ogden's residential campus while documenting historical events, I dove more into them, but I could not find the word "Y" system Ken had told me about in any documents for validation. My search led me to Dr. Grant B. Bitter's papers that he donated to the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah. His paper played a crucial role in validating the existence of the "Y" system. One of his papers stated, "Thus there would be a true dual system rather than the present "Y" system that forces all parents to place their children under oral programs until the 6th grade or 7th grade year." The date on which Dr. Bitter wrote his paper about this program is unknown. It appears that Dr. Bitter penned his paper in the early 1970s to prepare for the meeting that followed the replacement of the dual-track program with a two-track program, which eliminated the "Y" system in 1970. So, I'm grateful to Ken for telling me about the "Y" system and how it affected many families. Otherwise, we would not have known about it or understood what "Y" means when we ran across Dr. Bitter's paper.

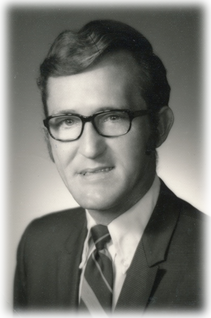

When Steven W. Noyce became superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind in 2009, his support for oral and mainstream education raised concerns within the Utah Deaf community. As a parent of Deaf children, I was worried that Steven Noyce would carry Dr. Grant B. Bitter's legacy by promoting oral education and mainstreaming all Deaf children in Utah. On November 3, 2009, I raised this issue with him and Associate Superintendent Jennifer Howell. I knew that Steven, a former student of Dr. Bitter's Oral Training Program at the University of Utah and a long-time employee at the Utah School for the Deaf, was fully aware of the controversy between oral and sign language. To protect the ASL/English bilingual program, I detailed Dr. Grant B. Bitter's controversial history of oral and mainstreaming advocacy, as well as the profound impact of the dual-track and two-track programs at the Utah School for the Deaf. I recommended providing an equal balance between the Listening and Spoken Language and ASL/English bilingual options for families of Deaf children. I also requested preventive measures to avoid the recurrence of similar issues. Steven acknowledged the accuracy of the information and said, "This is the most accurate paper I have ever read." This recognition of the paper's credibility underscores the importance of our advocacy efforts. I owe a debt of gratitude to my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, for sharing this critical history with me. His insights and knowledge have proven invaluable in our advocacy efforts for deaf education. Without his help, we couldn't have opposed the oral agenda.

Thank you, Ken!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Thank you, Ken!

Jodi Becker Kinner

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Nellie Sausedo, a remarkable individual who graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1967. Her contribution to this webpage is truly invaluable, as she shared her personal experience of the 1962 student strike at the school. Her story gave us a unique perspective on establishing the dual-track program, which divided the oral and sign language departments. Nellie was known for having an "elephant mind," and her enthusiasm for sharing stories about the school and its impact on students like herself is truly inspiring. If it weren't for her, this webpage would not have happened. Nellie, we are immensely grateful to you for playing a significant role in preserving and sharing this important story.

Thank you so much, Nellie!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Thank you so much, Nellie!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Utah School for the Deaf students

went on strike in 1962 and 1969

went on strike in 1962 and 1969

This piece of history is my favorite. I really appreciate the story that the students have shared. It's truly inspiring to hear about the brave actions of Ogden's residential school students who protested against the unfair "Y" System policy. It is heartbreaking to reflect on their social segregation from the oral and sign language departments

on the school campus during the strikes of 1962

and 1969, as well as their experiences in the

dual-track and two-track programs. Their courage and determination to stand up for their rights are truly admirable. Thank you for playing a significant role in preserving and sharing this important story.

~Jodi Becker Kinner~

on the school campus during the strikes of 1962

and 1969, as well as their experiences in the

dual-track and two-track programs. Their courage and determination to stand up for their rights are truly admirable. Thank you for playing a significant role in preserving and sharing this important story.

~Jodi Becker Kinner~

Opening of the Utah School for the Deaf

In 1884, a significant development in deaf education took place in Utah. The Utah School for the Deaf was established at the University of Deseret, later renamed the University of Utah, in Salt Lake City, as a territory school for Deaf students. John Beck and William Wood, parents of Deaf children, demonstrated remarkable perseverance in establishing the Utah School for the Deaf, which provides specialized education for Deaf students. Despite the challenges they faced, including the search for a qualified teacher and limited financial resources, they pressed on. After collecting data on the number of Deaf children in Utah, their request to open a new school for the Deaf was recognized and approved through the legislative process (Metcalf, 1898; The Utah Eagle, February 1922; Pace, 1946; Utah School for the Deaf Brochure, Evans, 1999). This significant milestone in Utah's deaf education history had a nationwide impact, setting a precedent for the establishment of similar institutions. The Utah School for the Deaf became a beacon of hope for Deaf students and their families in Utah and across the country.

Dr. John Rocky Park, the president of the University of Deseret, later renamed the University of Utah, also showed great determination when he took on the responsibility of setting up a classroom for Deaf students at the school. His search for a qualified Deaf teacher led him to the East in 1884, where he met Dr. Edward Miner Gallaudet, the president of Gallaudet College. Dr. Gallaudet's recommendation of Henry C. White, a Boston-based Deaf man who graduated from Gallaudet College in 1880, was a testament to the perseverance of these pioneers. On Dr. Gallaudet's recommendation, Dr. Park appointed Henry C. White as the principal and teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf (The Utah Eagle, February 1922; Evans, 1999). Although Henry did not establish the Utah School for the Deaf, he is credited with leading and maintaining it. Despite the school's limited financial resources and lack of support from the hearing community, Henry C. White served with distinction in his role.

On August 26, 1884, a room at the University of Deseret housed the establishment of the Utah School for the Deaf. This monumental event brought hope and opportunity to the Deaf community in Utah. Elizabeth Wood, the Deaf daughter of William Wood, who had been attending the Colorado School for the Deaf, joined Professor White on the first day of class (Fay, Histories of American Schools for the Deaf, 1817–1893). Shortly after, John Beck's three Deaf sons, Joseph, John, and Jacob, who were attending the California School for the Deaf, also joined the class (Evans, 1999). Professor Henry C. White, a visionary leader, was the school's first principal and served as a teacher, principal, and head teacher until 1890, shaping the school's early years with his dedication and expertise (Fay, 1893; Clarke, 1897; Metcalf, 1900; The Utah Eagle, February 1922; Pace, 1946). His leadership and the school's establishment marked a significant turning point in the history of Deaf education in Utah, providing a beacon of hope and a platform for the Deaf community to thrive.

Henry served as principal at the Utah School for the Deaf for five years before leaving in 1890. However, after the Milan Conference of 1880 passed a resolution mandating oralism in deaf education, the oral movement spread across the country. This movement threatened Henry's job, leading to his eventual replacement as principal in 1889 by Frank W. Metcalf, a hearing teacher from the Kansas School for the Deaf. This change reflected the growing emphasis on oralism in Utah and its impact on deaf education (Evans, 1999).

Frank took on the role of school principal in 1889, while Henry assumed the role of head teacher. However, their differing educational philosophies led to frequent disputes and animosity between them. The Board of Regents investigated and terminated Henry's employment with the school (The Utah Eagle, February 1922). In February 1890, he completely disassociated himself from the school (White, 1890; Fay, 1893; Pace, 1946; Burdett, Utah School for the Deaf Brochure). In 1894, while criticizing the school administrators for failing to consult with Deaf adults directly, Henry C. White stated, "What of the deaf themselves? Have they no say in a matter which means intellectual life and death to them?" (Buchanan p. 28).

Frank took on the role of school principal in 1889, while Henry assumed the role of head teacher. However, their differing educational philosophies led to frequent disputes and animosity between them. The Board of Regents investigated and terminated Henry's employment with the school (The Utah Eagle, February 1922). In February 1890, he completely disassociated himself from the school (White, 1890; Fay, 1893; Pace, 1946; Burdett, Utah School for the Deaf Brochure). In 1894, while criticizing the school administrators for failing to consult with Deaf adults directly, Henry C. White stated, "What of the deaf themselves? Have they no say in a matter which means intellectual life and death to them?" (Buchanan p. 28).

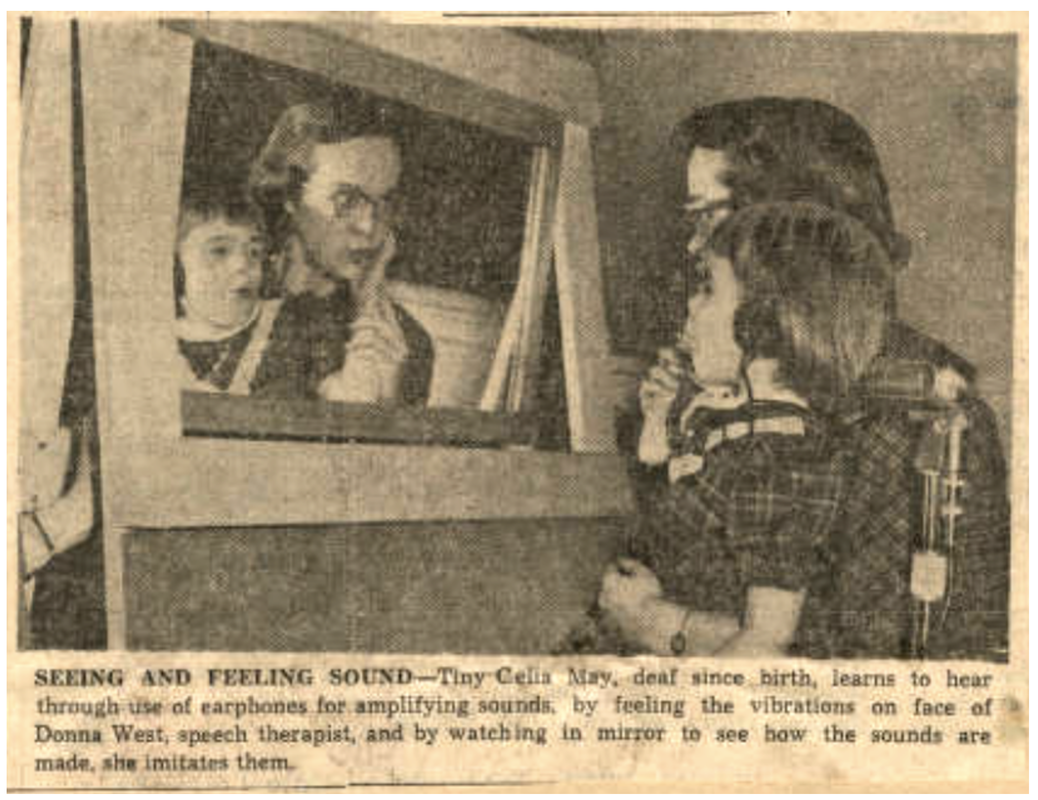

Beginning of Speech Training

In 1891, teaching speech to Deaf students was not a major focus in state schools. However, the Utah School believed teaching speech and lip-reading would benefit many students. As per Evans (1999, p. 29), around two-thirds of the students at the school received speech therapy. The school taught one class using speech and lip-reading, while the other two classes utilized a "combined system" that combined both sign language and speech (Pace, 1946; Evans, 1999). Florence Crandall Metcalf, a former teacher at the Kansas School for the Deaf and wife of the first superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf, Frank W. Metcalf, became an oral program teacher. She taught a class exclusively using the oral method (Fay, 1893).

Hearing parents wanted their children to learn to speak and read lips in an effort to integrate them into mainstream society. This has caused controversy, as Deaf individuals have been vocal in their opposition to this approach (Robert, 1994). The debate over whether to use the oral or signing method in deaf education has been ongoing for over 150 years without a definitive solution.

An Introduction of Combined System

In the early 1900s, the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, under the leadership of Superintendent Frank M. Driggs, who replaced Frank W. Metcalf, adopted a teaching method known as the combined method. To help Deaf students learn, this approach incorporated manual alphabet, sign language, speech, and speech reading. This method was widely used by state schools for the deaf across America at the time.

The school published a statement about its teaching methods in 1902. It explained that the combined method was the most effective way to educate students. Teachers believed education, including English acquisition, was more important than teaching speech and lip reading. When a child faced difficulties in learning speech, educators used the manual method, which involved using sign language. They viewed all the different communication approaches, such as speech, manual alphabet, writing, and sign language, as tools to help the student learn and succeed (Roberts, 1994, p. 61-62).

The school published a statement about its teaching methods in 1902. It explained that the combined method was the most effective way to educate students. Teachers believed education, including English acquisition, was more important than teaching speech and lip reading. When a child faced difficulties in learning speech, educators used the manual method, which involved using sign language. They viewed all the different communication approaches, such as speech, manual alphabet, writing, and sign language, as tools to help the student learn and succeed (Roberts, 1994, p. 61-62).

Frank M. Driggs, upon his appointment as superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf, faced the challenge of determining the most effective teaching methods for Deaf and hard of hearing children, as well as creating policies that would benefit both the children and their parents. Every parent who was worried about their Deaf child's ability to speak and read lips would approach him, asking, "Will my child be able to speak and read lips?" while pointing to their young Deaf child.

Superintendent Driggs believed in teaching Deaf children to speak but also recognized the conflict between the rigid oralism approach, which excluded signing, and the combined method. This conflict between the two philosophies has existed since the beginning of deaf education (UAD Bulletin, April 1959).

Superintendent Driggs believed in teaching Deaf children to speak but also recognized the conflict between the rigid oralism approach, which excluded signing, and the combined method. This conflict between the two philosophies has existed since the beginning of deaf education (UAD Bulletin, April 1959).

In the early 1900s, the Utah School for the Deaf employed teachers trained in the oral method to help students with their speaking and listening skills. Some of these teachers were also proficient in sign language. When a Deaf student had difficulty with speech or language development and couldn't communicate verbally, the oral teacher, who knew sign language, could use sign language to bridge the gap and help the student communicate effectively. This arrangement proved to be successful (Roberts, 1994).

Over time, the number of hearing parents who did not want their children to learn sign language increased. These parents wanted their children to be able to speak, read lips, and communicate mostly through residual hearing (Robert, 1994). This decision inspired the Utah School for the Deaf to create an oral program in 1943 to address these needs. The oral program's curriculum focused on lip-reading as well as spoken and written language (Pace, 1946).

Communication Methods of Instruction

at the Utah School for the Deaf

at the Utah School for the Deaf

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw the implementation of the oral program. Teachers primarily taught Deaf students orally, with no signing until the ninth grade. However, teachers allowed students to sign after school hours and in their dormitories. However, teachers often physically punished children for signing, striking them with erasers or yardsticks (Celia May Baldwin, personal communication, April 15, 2012).

The Utah School for the Deaf graduates of that era became the next generation of Deaf community leaders. They had firsthand experience with the harmful effects of oral instruction on Deaf students, knowing that these techniques compromised their educational standards. As the new Deaf leaders grew more active in academic issues, they discovered that the Utah Association of the Deaf provided them with a platform to speak out against these practices.

The Utah School for the Deaf graduates of that era became the next generation of Deaf community leaders. They had firsthand experience with the harmful effects of oral instruction on Deaf students, knowing that these techniques compromised their educational standards. As the new Deaf leaders grew more active in academic issues, they discovered that the Utah Association of the Deaf provided them with a platform to speak out against these practices.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson and Joseph B. Burnett, who both graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf, reported that in the 1950s, the school used three primary techniques for teaching: the manual method, the oral method, and the combined method. After experiencing all three methods, many Utah Association of the Deaf members developed a preference for the combined method. In 1955, the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) reaffirmed its support for the combined method of instruction for Deaf children during its convention, which was considered a significant show of support (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956).

Between 1955 and 1956, the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind announced to the public that they would use the oral method to teach elementary classrooms under Superintendent Harold W. Green's administration. After that, a gradual transition to the combined method would occur in the intermediate grades. In 1956, Joseph B. Burnett, president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, led a fierce campaign to prevent the inclusion of speech instruction in deaf education. The rest of the UAD officials supported him, believing that the combined method of instruction at the Utah School for the Deaf was the most valuable part of education. As a result of this controversy, the Utah Association of the Deaf opposed Superintendent Green's plan, arguing that early speech training for Deaf children had inherent disadvantages. They also claimed that oral philosophy violated the right to equal education for each Deaf child and hindered their academic progress (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956).

Around the same time, the Utah State Board of Education established a committee comprising eighteen citizens to scrutinize the teaching methods employed at the Utah School for the Deaf. Elmer H. Brown, from Salt Lake City, was appointed as the committee's chairman. Ray G. Wenger, Utah's most prominent Deaf advocate and the first Deaf representative to serve on the USDB Governor's Advisory Council, was also a member of the committee. The Utah Association of the Deaf (UAD) pledged their support for the investigation, contingent on its conduct being honest, fair, and impartial. However, the Deaf community had reservations regarding the investigation (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956).

In April 1958, the Governor's Advisory Committee for the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind reappointed Ray G. Wenger, a 1913 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf. Ray G. Wenger, having served on the Governor's Advisory Committee for the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind since 1945, received another appointment in April 1958. The UAD welcomed Ray's appointment because he strongly supported the combined method in educational settings (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956). Additionally, Ray is believed to be the first Deaf member of the advisory committee.

To prevent any bias or prejudice that could influence the outcome of an investigation, the Utah Association of the Deaf requested an equal hearing of all points of view. The investigating committee heard from the Utah Association of the Deaf, mainly comprised of graduates of the Utah School for the Deaf, about their perspectives on educational approaches for Deaf children. The discussions were also open to educators, parents, and the general public. During the investigation, Deaf adults emphasized to the committee that the Utah School for the Deaf, which is the state's official residential school for the deaf, provided the best possible education for Deaf students. This school also offered an excellent vocational education program to Deaf students when they reached adolescence, giving them an edge over hearing children in preparing for future employment. Most Deaf students who enrolled in this program found jobs right after graduation. A residential school provided a better social life for Deaf children, according to Deaf adults. They also felt that parents should be aware that relying solely on the oral method was insufficient to teach their Deaf child in many areas, based on their own experiences of being pushed into an inadequate oral program (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956).

To prevent any bias or prejudice that could influence the outcome of an investigation, the Utah Association of the Deaf requested an equal hearing of all points of view. The investigating committee heard from the Utah Association of the Deaf, mainly comprised of graduates of the Utah School for the Deaf, about their perspectives on educational approaches for Deaf children. The discussions were also open to educators, parents, and the general public. During the investigation, Deaf adults emphasized to the committee that the Utah School for the Deaf, which is the state's official residential school for the deaf, provided the best possible education for Deaf students. This school also offered an excellent vocational education program to Deaf students when they reached adolescence, giving them an edge over hearing children in preparing for future employment. Most Deaf students who enrolled in this program found jobs right after graduation. A residential school provided a better social life for Deaf children, according to Deaf adults. They also felt that parents should be aware that relying solely on the oral method was insufficient to teach their Deaf child in many areas, based on their own experiences of being pushed into an inadequate oral program (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956).

The Utah School for the Deaf graduates and individuals affiliated with the Utah Association of the Deaf advocated for the necessary improvement of Deaf children's academic skills in reading, writing, and mathematics to provide them with a quality education. They further asserted that mastering these fundamental subjects facilitates the acquisition of essential social skills such as lip-reading and speech. The group expressed concern about the lack of a clear direction for the educational program at the Utah School for the Deaf. They believe that USD needs to establish concrete goals for students regarding college preparedness. Deaf high school students were unprepared for college and unaware of the benefits of higher education. Deaf adults suggest that the Utah School for the Deaf should begin college preparation in the first year of high school and design the entire high school academic program around college entry criteria (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956).

The Utah Association of Deaf officials and the Utah School for Deaf graduates aimed to convey to the hearing community that Deaf students were capable of receiving academic instruction and access to a comprehensive education. During the investigative committee, the Deaf adults clearly stated this sentiment, emphasizing that education was more important than speech. Here's the quote:

“EDUCATION IS MORE IMPORTANT TO THE DEAF THAN THE MERE ABILITY TO SPEAK AND READ LIPS! And the most efficient and quickest way to educate Deaf children is competent application of the Combined Method” (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955-1956, p. 3).

When the study came to a close, the outcome was unknown, despite the fact that Deaf adults and the Utah Association of Deaf officials had put in a lot of effort and time presenting papers to the educators and committee. Unfortunately, nothing changed in the scenario. They were surprised and disappointed. Following the incident, the Utah School for the Deaf implemented two communication programs: an oral program and a simultaneous communication program that combines both voice and sign language at the same time. Nonetheless, there appeared to be a lack of attention and concern towards deaf education (Burnett & Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, 1955–1956).

On March 19, 1959, the UAD Committee on Deaf Education visited the Utah School for the Deaf to discuss the school's programs with administrators. The committee consisted of Ned C. Wheeler, G. Leon Curtis, Gladys Burnham Wenger, Arthur W. Wenger, and Robert G. Sanderson, all of whom were the Utah School for the Deaf graduates. Ray's twin Deaf brother, Arthur W. Wenger, was absent that day. The committee needed more time to evaluate the academic outcomes of the school's various methods. They couldn't say whether they were effective or whether the Deaf children's education was adequate. Nevertheless, the committee members, who are alums, felt they had a right to request that the Utah School for the Deaf administration officials keep them informed of the students' academic and professional achievements.

Despite the growing popularity of small oral day schools that posed a threat to the Utah Association of the Deaf, the UAD Committee for Deaf Education unanimously agreed that the Utah School for the Deaf was still the best place for a Deaf child to receive a comprehensive education and acquire sufficient vocational skills to become a valuable member of society (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, April 1959).

Despite the growing popularity of small oral day schools that posed a threat to the Utah Association of the Deaf, the UAD Committee for Deaf Education unanimously agreed that the Utah School for the Deaf was still the best place for a Deaf child to receive a comprehensive education and acquire sufficient vocational skills to become a valuable member of society (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, April 1959).

Ray G. Wenger Addresses

Congressional Committee

Congressional Committee

Ray and Arthur Wenger, known as Utah's Famous Twin Team and 1913 Utah School for the Deaf graduates, traveled to Los Angeles, California, on July 16, 1960, to attend an important meeting. Ray was scheduled to speak before a U.S. House of Representatives committee about a federal bill that would provide training for Deaf teachers. However, the original bill did not have provisions to prevent discrimination against Deaf educators seeking employment. The Utah Association of Deaf officials lobbied to amend the bill, and Ray's testimony added to the combined method's defense with a powerful and effective presentation. The congressional hearing report included his remarks, leaving a lasting impression on the House Committee members (UAD Bulletin, Fall 1960). However, the Utah Association of the Deaf eventually faced an unexpected shift in 1962 when Dr. Grant B. Bitter came into the picture, which has had a long-term impact on the deaf educational system in Utah.

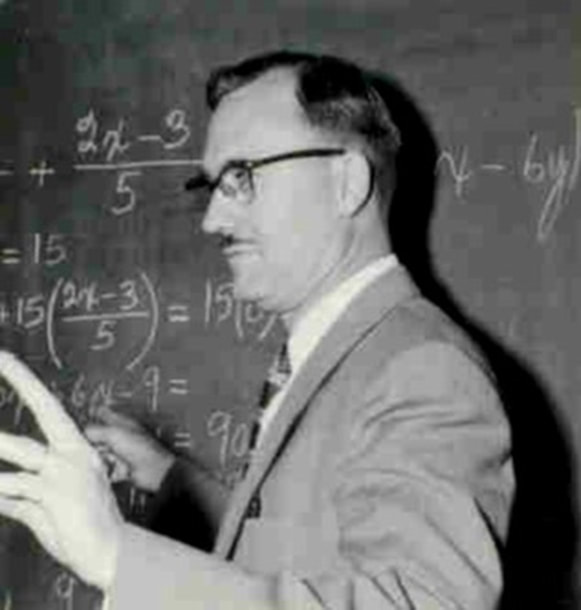

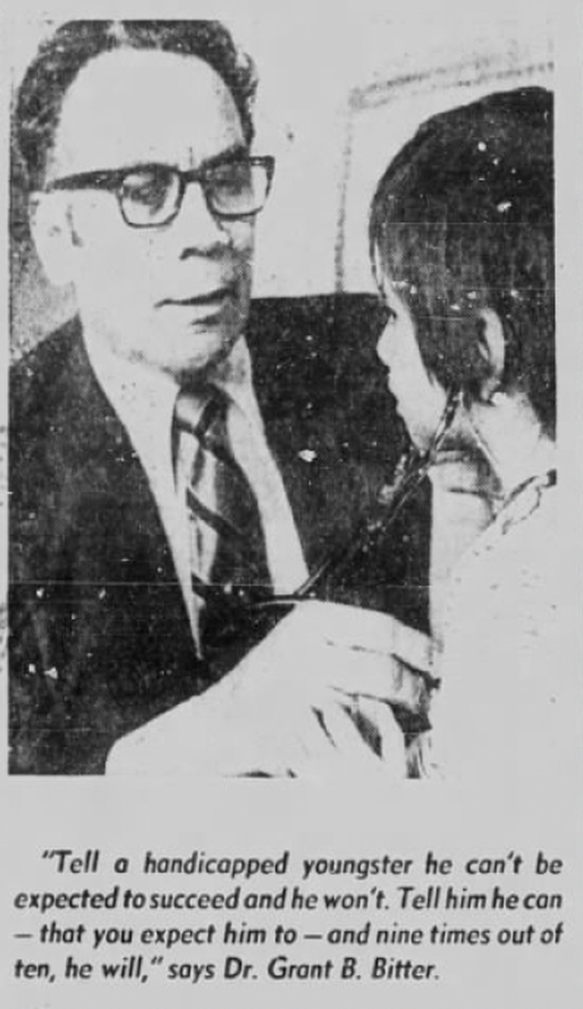

Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

the Father of Mainstreaming

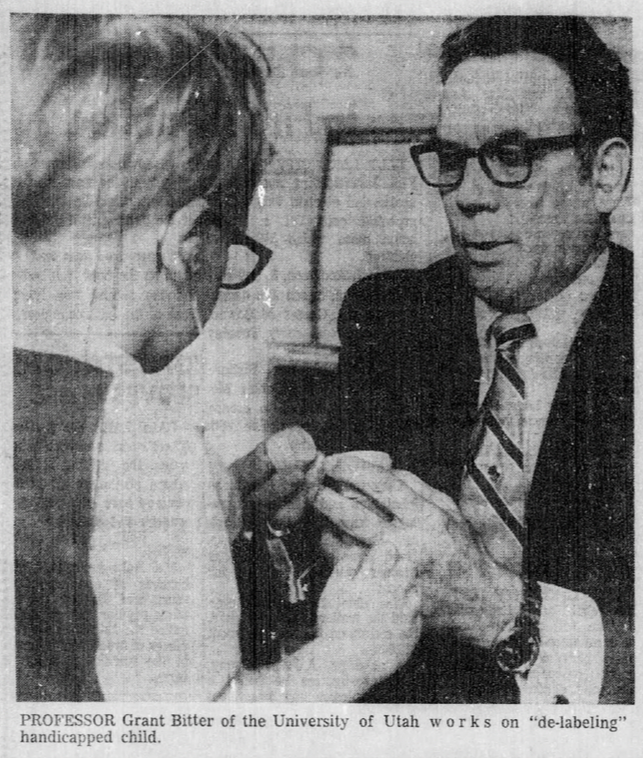

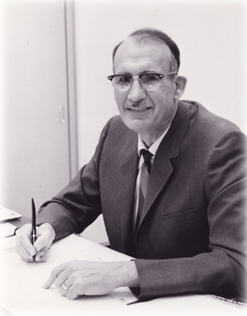

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter, who opposed anyone who stood in the way of his goals of promoting oral and mainstream education, has formally requested the job removal of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, both respected advocates for sign language. He believed they were interfering with his mission. Additionally, he expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, feeling it did not align with his educational goals. He also asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected committee chairperson, to resign because she invited representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he saw as a shift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf, in the face of Dr. Bitter's opposition, demonstrated remarkable resilience, marking a significant turning point in their history and inspiring others with their strength and determination.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. His journey began at the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked as a teacher and curriculum coordinator. His passion for education led him to become a director and professor in the Teacher Training Program, where he focused primarily on oral education under the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. Dr. Bitter also served as the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

The Implementation of the Dual-Track Program,

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

In the fall of 1962, the Utah Deaf community was surprised by the revolutionary changes at the Utah School for the Deaf, which introduced the dual-track program, also commonly known as the "Y" system. The unexpected change had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children, evoking a sense of empathy within the community. The Utah Association of the Deaf, which advocated for sign language, was unaware that the Utah Council for the Deaf had spearheaded the change, advocating for speech-based instruction and successfully pushing for its implementation at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962). It is believed that Dr. Bitter was a member of this council. The dual-track program provided an oral program in one department and a simultaneous communication program in another department, which was later replaced by a combined system. However, the dual-track policy mandated that all Deaf children begin with the oral program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Gannon, 1981). The Utah State Board of Education, a key player in educational policy, approved this policy reform on June 14, 1962, with endorsement from the Special Study Committee on Deaf Education (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). The newly hired superintendent, Robert W. Tegeder, accepted the parents' proposals and initiated changes to the school system (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter, 1962; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). This new program not only affected the lives of Deaf children but also their families.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

As a result of the "Y" system's implementation, the Utah School for the Deaf had to undergo significant changes. The school had to hire more oral teachers and establish speech as the primary mode of communication, shifting the focus of the learning environment. The dual-track program initially placed all elementary school students in the oral department, transferring them to the simultaneous communication department only if they failed in the oral program. This approach was based on the belief that early development of oral skills was crucial for Deaf students, with sign language learning considered a secondary focus. The change in focus and the increased hiring of oral teachers had a significant impact on the school's learning environment, altering its dynamics and atmosphere (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The Utah School for the Deaf has used the combined method in its classrooms since 1902. This method involved a combination of manual signing, speech, and listening until the 1950s. The creation of more extension classrooms revealed parents' desire for their children to improve their speaking and listening abilities. Therefore, they prohibited signing in oral classes. Until ninth grade, oral classrooms prohibited Deaf students from signing, but this restriction only applied during class hours. Students could sign after school and in the dorms. Elementary school students received basic speaking skills instruction from hearing teachers, while Deaf high school students received instruction exclusively from Deaf teachers (Celia May Baldwin, personal communication, April 15, 2012).

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

The Utah School for the Deaf has used the combined method in its classrooms since 1902. This method involved a combination of manual signing, speech, and listening until the 1950s. The creation of more extension classrooms revealed parents' desire for their children to improve their speaking and listening abilities. Therefore, they prohibited signing in oral classes. Until ninth grade, oral classrooms prohibited Deaf students from signing, but this restriction only applied during class hours. Students could sign after school and in the dorms. Elementary school students received basic speaking skills instruction from hearing teachers, while Deaf high school students received instruction exclusively from Deaf teachers (Celia May Baldwin, personal communication, April 15, 2012).

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

The "Y" system, used as a decision-making tool, determined a student's educational placement in the dual-track program. For instance, in the oral department, a Deaf student would progress from preschool to sixth grade. After that, a committee would evaluate the student's speaking ability, school performance, test results, and family environment to decide whether to continue in the oral program or transfer to the simultaneous communication program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). Regardless of whether they studied on the Ogden campus or in the Extension Division classrooms, established in 1959 to promote mainstreaming for Deaf children, the program expected all Deaf children to enroll in the entire oral department (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970; The Utah Eagle, February 1968). As a result, the Salt Lake Extension Program became almost as big as Ogden's residential school. Unfortunately, these regulatory changes had a detrimental impact on Ogden's residential school for many years, raising concerns about the future of Deaf education.

At the time, teachers had to obtain a bachelor's degree in deaf education from an accredited teacher center and receive certification. Teachers who taught simultaneous communication also needed to be proficient in sign language (The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

A new "Y" policy at the Utah School for the Deaf resulted in a sudden shortage of oral teachers (The Utah Eagle, November 1962). To fill this gap, the Utah School for the Deaf employed the University of Utah's Teacher Training Program, an 'army of oral teachers.' Gallaudet College guided teachers in the simultaneous communication department, whereas the University of Utah assisted teachers in the oral department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Dr. Bitter is likely to get the idea for the new policy from his internship at the Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school in New York, during his master's degree studies (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

A new "Y" policy at the Utah School for the Deaf resulted in a sudden shortage of oral teachers (The Utah Eagle, November 1962). To fill this gap, the Utah School for the Deaf employed the University of Utah's Teacher Training Program, an 'army of oral teachers.' Gallaudet College guided teachers in the simultaneous communication department, whereas the University of Utah assisted teachers in the oral department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Dr. Bitter is likely to get the idea for the new policy from his internship at the Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school in New York, during his master's degree studies (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

The Effects of the Dual-Track and Two-Track Programs on the Kinner Family

This section describes Kenneth L. Kinner's experiences as a 1954 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf and how it affected the family. Kenneth had a Deaf daughter named Deanne, who was born in 1961, a year before the implementation of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. Kenneth's firsthand experience with the new dual-track program, which began in the fall of 1962, required his daughter to start the oral program at four and a half in 1965, despite her first language being American Sign Language (ASL). This program aimed solely at teaching speech skills, which forced parents like Kenneth and his wife, Ilene Coles, a 1959 graduate who preferred sign language, to enroll their children in it. Students who were unable to learn how to speak were eventually enrolled in the simultaneous communication department, a part of the dual-track program that focused on teaching both sign language and speech. However, in the "Y" system channel, a policy mandated that parents wait until their child completed their first six years of education or was 12 years old to enroll in sign language education in the simultaneous communication department, preventing Deanne from switching to the program she wanted until she turned 12. The oral program's goal was to enable all students to excel in their oral abilities, marking the start of a new war against the system (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). Deanne shared that she had wanted to switch to the simultaneous communication program during her childhood, but due to the "Y" policy, her father kept telling her that he could not transfer her until she turned 12. Only after reaching this age could she finally switch to the program she desired (Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

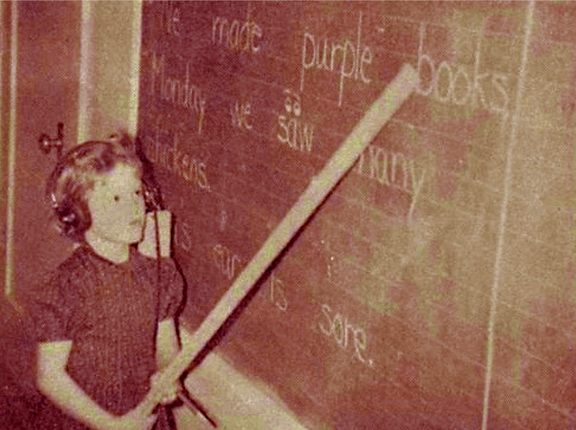

One incident in the oral program was that while a substitute oral teacher was writing on the blackboard and talking, Deanne, who was seven, was reading from the textbook. She could hear constant sounds with her hearing aid, but she couldn't read lips from the back of the teacher’s head. Often, Deanne would read from the book and then answer the teacher's questions. However, this time, the teacher kept calling her name while she was looking down and reading. Typically, she couldn't identify the caller due to the continuous background noise. After repeatedly calling her name, the teacher hit her with a stick and asked, "Why didn't you hear me when I called your name?" Deanne was stunned, but she remained calm until recess. Once outside, she hurriedly walked to her father's workplace, showing her arm to him while crying. His boss saw her crying and instructed her father to take her to school, where Ken reported the incident. The school apologized (Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024). This incident nonetheless prompted a need for change.

One incident in the oral program was that while a substitute oral teacher was writing on the blackboard and talking, Deanne, who was seven, was reading from the textbook. She could hear constant sounds with her hearing aid, but she couldn't read lips from the back of the teacher’s head. Often, Deanne would read from the book and then answer the teacher's questions. However, this time, the teacher kept calling her name while she was looking down and reading. Typically, she couldn't identify the caller due to the continuous background noise. After repeatedly calling her name, the teacher hit her with a stick and asked, "Why didn't you hear me when I called your name?" Deanne was stunned, but she remained calm until recess. Once outside, she hurriedly walked to her father's workplace, showing her arm to him while crying. His boss saw her crying and instructed her father to take her to school, where Ken reported the incident. The school apologized (Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024). This incident nonetheless prompted a need for change.

After nearly ten years of battle, the newly formed "two-track program" replaced the dual-track system in 1970, thereby eliminating the "Y" system. The two-track system allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their Deaf child aged between 2 1/2 and 21. This new two-track approach allowed their Deaf son, Duane, who was 11 years younger than Deanne, to begin to enter the total communication program at the age of three in 1975 (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011).

When Deanne was ten years old, her parents quickly removed her from the oral program in the fall of 1971, under the new two-track system, and placed her in the total communication program. This change in the educational system was considered a big step forward. Testing revealed that Deanne, who had grown up with language access at home, was at or above the academic level. Despite being placed with middle-and high-school-aged kids who were performing below academic level, she persevered. Her friends, who had hearing parents, remained in the oral program. Deanne, the youngest student in the total communication program, found herself placed with the 15, 16, and 17 year-old students who had been deprived of language in the oral program. This environment had a profound impact on her emotional, social, and educational growth. She was exposed to inappropriate information for her age and was forced to mature and persevere quickly in the two-track program, a challenge that she faced with remarkable strength.

Although Duane grew up with total communication and was free to communicate in ASL, the trend toward mainstreaming grew, and enrollment at the Utah School for the Deaf declined. With Deanne's encouragement, using her trauma from childhood experiences as evidence, she helped convince her parents to transfer Duane to the Idaho School for the Deaf in 1987. Duane thrived in this new environment, benefiting from a better education and access to peers who were his age. Furthermore, several of his age group classmates from the Utah School for the Deaf transferred out of state to attend residential schools across the United States, where they were able to get better education, social opportunities, extracurricular activities, and so on (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

Having said that, it is important to recognize the challenges that Deaf students and their families faced while advocating for their right to access educational opportunities that met their academic and social needs. These challenges included navigating complex educational systems, advocating for the use of effective communication methods, and ensuring access to appropriate learning environments. You can find more details about the two-track program and the challenges it posed further down the webpage.

When Deanne was ten years old, her parents quickly removed her from the oral program in the fall of 1971, under the new two-track system, and placed her in the total communication program. This change in the educational system was considered a big step forward. Testing revealed that Deanne, who had grown up with language access at home, was at or above the academic level. Despite being placed with middle-and high-school-aged kids who were performing below academic level, she persevered. Her friends, who had hearing parents, remained in the oral program. Deanne, the youngest student in the total communication program, found herself placed with the 15, 16, and 17 year-old students who had been deprived of language in the oral program. This environment had a profound impact on her emotional, social, and educational growth. She was exposed to inappropriate information for her age and was forced to mature and persevere quickly in the two-track program, a challenge that she faced with remarkable strength.

Although Duane grew up with total communication and was free to communicate in ASL, the trend toward mainstreaming grew, and enrollment at the Utah School for the Deaf declined. With Deanne's encouragement, using her trauma from childhood experiences as evidence, she helped convince her parents to transfer Duane to the Idaho School for the Deaf in 1987. Duane thrived in this new environment, benefiting from a better education and access to peers who were his age. Furthermore, several of his age group classmates from the Utah School for the Deaf transferred out of state to attend residential schools across the United States, where they were able to get better education, social opportunities, extracurricular activities, and so on (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

Having said that, it is important to recognize the challenges that Deaf students and their families faced while advocating for their right to access educational opportunities that met their academic and social needs. These challenges included navigating complex educational systems, advocating for the use of effective communication methods, and ensuring access to appropriate learning environments. You can find more details about the two-track program and the challenges it posed further down the webpage.

The Main Building

of the Utah School for the Deaf

of the Utah School for the Deaf

In 1962, the Utah School for the Deaf introduced the

dual-track program in the Main Building, known as

the "Y" System. At that time, the U-shaped Main

Building on Ogden's residential campus housed the

oral and simultaneous communication departments

in separate wings. As shown in the picture above,

the oral department was on the left, while the

simultaneous communication department was on the right (Utahn, 1957; The Utah Eagle, February 1968)

In 1962, the Utah School for the Deaf introduced the

dual-track program in the Main Building, known as

the "Y" System. At that time, the U-shaped Main

Building on Ogden's residential campus housed the

oral and simultaneous communication departments

in separate wings. As shown in the picture above,

the oral department was on the left, while the

simultaneous communication department was on the right (Utahn, 1957; The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

dual-track program in the Main Building, known as

the "Y" System. At that time, the U-shaped Main

Building on Ogden's residential campus housed the

oral and simultaneous communication departments

in separate wings. As shown in the picture above,

the oral department was on the left, while the

simultaneous communication department was on the right (Utahn, 1957; The Utah Eagle, February 1968).

The Student Protest of 1962

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, the Utah School for the Deaf made changes without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were shocked to learn about the changes. The dual-track program at Ogden's residential campus also caused drawbacks due to the strict social segregation environment. The oral program prevented Deaf students from interacting with their peers in the signing department, resulting in a lack of social interaction. This also meant that friends in different programs couldn't see each other during class or recess. The school's decision to separate one high school sweetheart was a clear example of the program's damaging effects (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). The new social segregation policy under the dual-track program has caused emotional and mental trauma for many students.

These changes also caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy, as detailed in the following webpage below.

During the 1962–63 school year, the Utah School for the Deaf made changes without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were shocked to learn about the changes. The dual-track program at Ogden's residential campus also caused drawbacks due to the strict social segregation environment. The oral program prevented Deaf students from interacting with their peers in the signing department, resulting in a lack of social interaction. This also meant that friends in different programs couldn't see each other during class or recess. The school's decision to separate one high school sweetheart was a clear example of the program's damaging effects (Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). The new social segregation policy under the dual-track program has caused emotional and mental trauma for many students.

These changes also caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy, as detailed in the following webpage below.

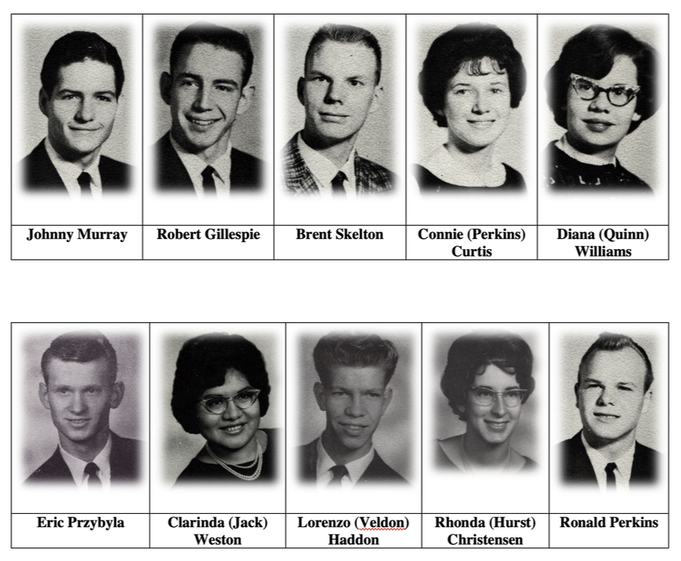

Over half of the high school students staged a strike on the third Friday of September 14th, 1962, over the social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus. Johnny Murray, a senior, was the leader protesting against the changes. He recalled a strange visit from Tony Christopulos, who was the principal of the Utah School for the Deaf, an oral advocate, and one of Dr. Bitter's right-hand men. Tony visited Johnny's home just before the start of the school year and asked his parents if they wanted their son to join the oral program. After Tony left, Johnny's parents asked him whether he wanted to enroll in the oral program. Johnny replied with a clear "No" (Johnny Murray, personal communication, August 14, 2009).

Johnny finally understood the reason behind the odd visit on the first day of school. The school administration had recently introduced a new policy called "Y," which allowed parents of older students attending the Utah School for the Deaf to choose their child's placement. The administration had contacted all parents to learn about their placement preferences. The oblivious parents were content to follow the administration's advice and enroll their children in the oral program. Unlike the other parents, Murray asked Johnny about their preferences before making any decision (Johnny Murray, personal communication, August 14, 2009).

Johnny finally understood the reason behind the odd visit on the first day of school. The school administration had recently introduced a new policy called "Y," which allowed parents of older students attending the Utah School for the Deaf to choose their child's placement. The administration had contacted all parents to learn about their placement preferences. The oblivious parents were content to follow the administration's advice and enroll their children in the oral program. Unlike the other parents, Murray asked Johnny about their preferences before making any decision (Johnny Murray, personal communication, August 14, 2009).

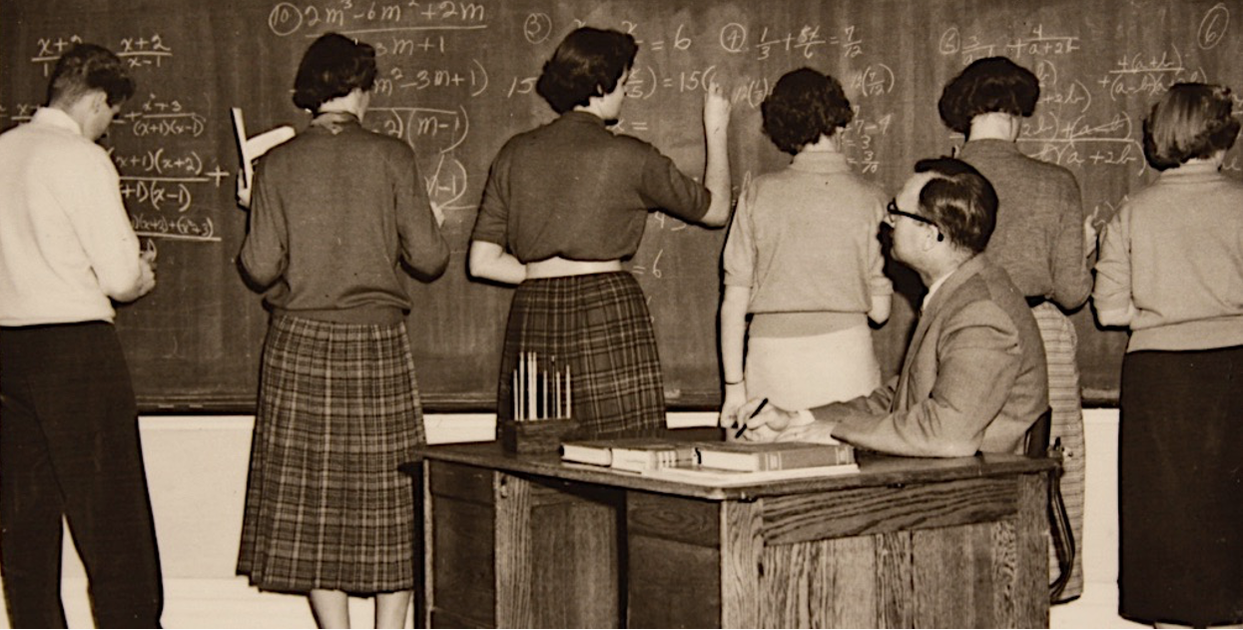

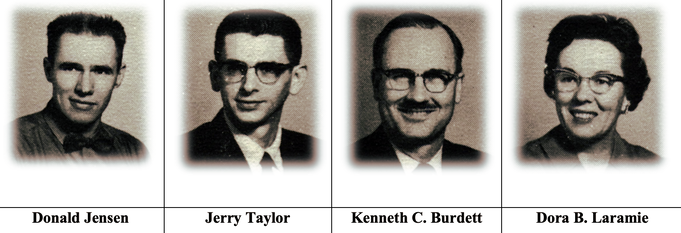

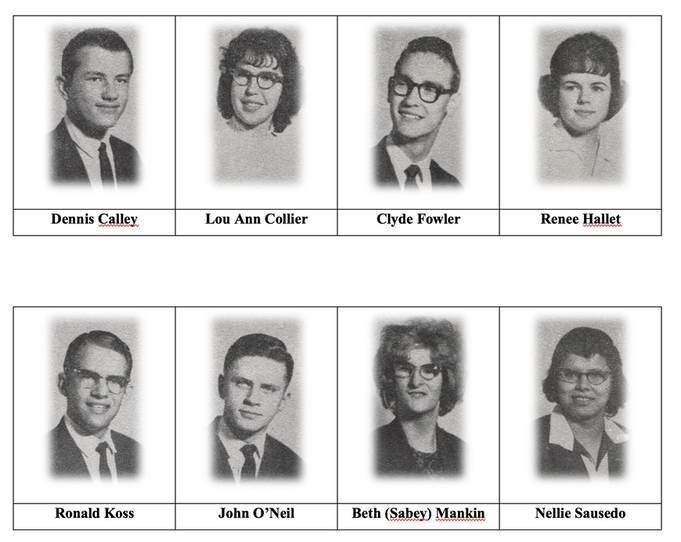

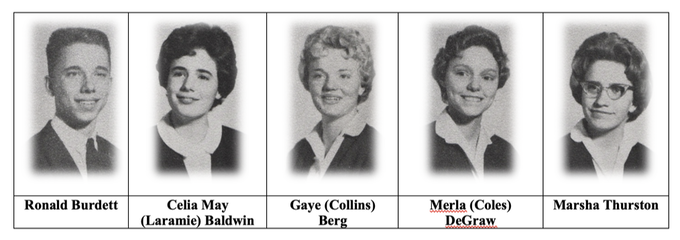

The students were worried about the dual-track program and its potential effects. They were especially concerned about possibly losing their well-liked and respected Deaf teachers. These teachers included Donald Jensen, Jerry Taylor, Kenneth C. Burdett, father of Ronald Burdett, sophomore, and Dora B. Laramie, mother of Celia May "C.M." Laramie Baldwin, also sophomore (Johnny Murray, personal communication, August 14, 2009; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011).

Johnny Murray, a senior and Student Council president, organized a protest with the support of 25 high school students from the simultaneous communication program. The students spent a week making posters and writing "Strike," "Unfair," and "Listen to Us" on them, using shoe polish and wooden sticks to prop them up. The Utah School for the Deaf teachers, including the four Deaf teachers, had no idea they were going on strike (The Ogden Standard Examiner, September 14, 1962; Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007; Celia May Laramie Baldwin, personal communication, April 1, 2024).

After completing their secret preparations, some of the students attended a seminary class of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on September 14, 1962, under the instruction of a Deaf instructor named G. Leon Curtis. After the seminary class, they went to the gym to meet with non-Latter-day Saints students and collect the posters. At 8:30 a.m., the students marched, holding the posters, into the hallway of the Main Building, starting from the gym, where their classrooms were located (The Ogden Standard Examiner, September 14, 1962; Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007).

After completing their secret preparations, some of the students attended a seminary class of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on September 14, 1962, under the instruction of a Deaf instructor named G. Leon Curtis. After the seminary class, they went to the gym to meet with non-Latter-day Saints students and collect the posters. At 8:30 a.m., the students marched, holding the posters, into the hallway of the Main Building, starting from the gym, where their classrooms were located (The Ogden Standard Examiner, September 14, 1962; Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007).

During a protest, Ronald Burdett noticed that his father, Kenneth C. Burdett, smiled slightly as he understood the purpose of the protest. However, he didn't feel comfortable participating in the protest as he was concerned about keeping his job. Some of the hearing teachers were shocked and disgusted with the protesting students. They thought the students were being silly for going on strike. One of the teachers, Thomas Van Drimmelen, got angry and tried to pull Celia May Laramie Baldwin out of the march. Dora B. Laramie, C.M.'s hard of hearing mother, shouted at him to stop pulling her out of the march, yelling, "Don't touch C.M.!" (Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007).

The Ogden Standard Examiner reported that by noon, some students' whereabouts were unknown (Ogden Standard Examiner, September 14, 1962). Two teachers searched for them while they marched from the USD campus to Lorin Farr Park. The students hid behind the trees as their car passed by to avoid being seen. They thought of going to a movie theater but found it closed at 10 a.m. Instead, they went to Ronald Burdett's backyard to relax and hang out. Feeling hungry, they pooled their money and sent someone to the nearby grocery shop on 26th and Quincy Avenue to buy cookies and punch for their lunch (Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007; Ronald Burdett, personal communication, 2007).

When Kenneth C. Burdett returned home from work, he was surprised to find the students at his place. Fearing for their safety and his potential termination, he promptly brought them to the Utah School for the Deaf. After that, students returned to their homes for the weekend (Ronald Burdett, personal communication, 2007).

When Kenneth C. Burdett returned home from work, he was surprised to find the students at his place. Fearing for their safety and his potential termination, he promptly brought them to the Utah School for the Deaf. After that, students returned to their homes for the weekend (Ronald Burdett, personal communication, 2007).

Seniors

Juniors

Sophomores

Tony Christopoulos, the principal of the Utah School for the Deaf, suggested in an article in the Ogden Standard-Examiner that unhappy parents initiated the recent student protest. He stated that the parents of the protesting students had influenced their decision to go on strike. Moreover, Tony made it clear that only the Deaf students in the simultaneous communication department were unhappy with the changes, while the 52 Deaf students in the oral department did not participate in the protest (Ogden Standard Examiner, September 14, 1962). Without any external influence, the simultaneous communication students protested independently and expressed their desire to remain together as before the changes.

On Monday, September 17, 1962, Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder arranged a meeting with students to discuss the strike. During the meeting, Superintendent Tegeder, torn between his duty and personal beliefs, asked the students why they went on strike. With a courage that would inspire generations to come, the students counterbacked by questioning the existence of two departments on campus and the disparity in the number of students enrolled in each department, as quoted: "Why do we have two departments on campus?" and "Why does the oral department have more students than the simultaneous communication department? Despite his disagreement with the changes, he had to support the new policy. He couldn't think of any other response except saying, "Oh well!" (Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007).

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder highlighted in an article in the Ogden Standard-Examiner that the walkout of 25 students at the Utah School for the Deaf was not only an act of defiance, but also a strong statement of their needs. The students, who felt limited in their social interactions and dissatisfied with the school's separate facilities, decided to take matters into their own hands. They yearned for more social interaction with the 52 other students in the oral program and expressed unhappiness with the separation of the classrooms, dormitory rooms, and playground areas. Superintendent Tegeder shared their feelings and admitted, "I'm dissatisfied with many of these myself." He further explained that some of the students had been living in dorms together for eight years, and the new teaching program forced them to separate from their old friends, which had taken an emotional toll on them (Ogden Standard Examiner, September 14, 1962).

Nellie Sausedo recalled when she and some students protested against the school's policy of segregating them into dormitories, dining rooms, and classes such as physical education, cooking, sewing, printing, and school events. The students were unhappy with this segregation and missed the days when everyone could be together in the same room at the same time. They were particularly upset about the signing restrictions and felt that the situation was becoming unacceptable. Nellie, one of the protesters, expressed that "no one listened" (Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007). Despite the students' efforts to intervene, the school administration persisted with the dual-track policy.

Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder highlighted in an article in the Ogden Standard-Examiner that the walkout of 25 students at the Utah School for the Deaf was not only an act of defiance, but also a strong statement of their needs. The students, who felt limited in their social interactions and dissatisfied with the school's separate facilities, decided to take matters into their own hands. They yearned for more social interaction with the 52 other students in the oral program and expressed unhappiness with the separation of the classrooms, dormitory rooms, and playground areas. Superintendent Tegeder shared their feelings and admitted, "I'm dissatisfied with many of these myself." He further explained that some of the students had been living in dorms together for eight years, and the new teaching program forced them to separate from their old friends, which had taken an emotional toll on them (Ogden Standard Examiner, September 14, 1962).

Nellie Sausedo recalled when she and some students protested against the school's policy of segregating them into dormitories, dining rooms, and classes such as physical education, cooking, sewing, printing, and school events. The students were unhappy with this segregation and missed the days when everyone could be together in the same room at the same time. They were particularly upset about the signing restrictions and felt that the situation was becoming unacceptable. Nellie, one of the protesters, expressed that "no one listened" (Nellie Sausedo, personal communication, 2007). Despite the students' efforts to intervene, the school administration persisted with the dual-track policy.

After the implementation of the dual-track program and the end of a student protest, Tony Christopulos asked high school Deaf students from the simultaneous communication program to promote unity and acceptance in light of the new "Y" system changes. During the meeting, he drew on the chalkboard to illustrate the concepts of the 'Deaf World' and 'Hearing World.' He warned the students against isolating themselves in the Deaf World, which he marked with an X. Instead, he emphasized the importance of integrating into the hearing world, which he circled (Ronald Burdett, personal communication, 2007). Tony's college education, which heavily emphasized oral instruction, shaped his perspective on integrating Deaf students into the hearing world.