Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

Written & Compiled by Jodi Becker Kinner

Published in 2015

Updated in 2024

Published in 2015

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

Through my father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, who graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf in 1954 and is the father of two Deaf children named Duane and Deanne, I had the fortunate opportunity to learn about the life and legacy of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a renowned oral and mainstream education advocate. Dr. Bitter's profound influence on deaf education in Utah caught my attention, thanks to Kenneth's storytelling. Dr. Bitter's ideologies have had a long-lasting impact on the education of Deaf children in Utah. He was the driving force behind Utah's movement in the 1960s to mainstream all Deaf children, which was a transformative moment for a parent of a Deaf daughter like him that earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' Without Kenneth's recollections, Dr. Bitter's influence, and his challenger, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who staunchly supported sign language and state schools for the deaf who engaged in battle with Dr. Bitter, I wouldn't have been able to write about this important history. I've compiled a webpage detailing Dr. Bitter's career and education, so you can learn more about him. If you want to understand his impact on deaf education in Utah, I recommend reading the "Deaf Education History in Utah" webpages. Finally, you can find a collection of Dr. Bitter's videos on the webpage below.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Who is Dr. Grant B. Bitter?

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter, who opposed anyone who stood in the way of his goals of promoting oral and mainstream education, has formally requested the job removal of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, both respected advocates for sign language. He believed they were interfering with his mission. Additionally, he expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, feeling it did not align with his educational goals. He also asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected committee chairperson, to resign because she invited representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he saw as a shift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf, in the face of Dr. Bitter's opposition, demonstrated remarkable resilience, marking a significant turning point in their history and inspiring others with their strength and determination.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. He obtained his bachelor's degree from the University of Utah. Before joining the Utah School for the Deaf, he worked as a religious education teacher. From 1950 to 1958, he taught the seminary class of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Subsequently, he received a scholarship to the Lexington School for the Deaf, affiliated with Columbia University, in New York City, where he earned a master's degree and a special education certificate while interning at the school from 1961 to 1962. Upon completion of his master's degree, he returned to Utah and began teaching in the Oral Extension classes of the Utah School for the Deaf in the Salt Lake City School District from 1962 to 1964 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children...At High Risk, 1986; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

After completing his doctorate in audiology, rehabilitation, and administrative-educational administration with a focus on special education at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, in the summer of 1967, he returned to Utah after three years of schooling. He worked at the University of Utah and also became the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987; Obituary: Grant Bunderson Bitter, Deseret News, July 2, 2000; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

After completing his doctorate in audiology, rehabilitation, and administrative-educational administration with a focus on special education at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, in the summer of 1967, he returned to Utah after three years of schooling. He worked at the University of Utah and also became the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987; Obituary: Grant Bunderson Bitter, Deseret News, July 2, 2000; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

From 1967 to 1969, Dr. Bitter worked as the Extension Division Curriculum Coordinator in Salt Lake City, Utah. He resigned from this coordinator position in 1969 due to increasing job demands. Additionally, he held part-time positions as the Coordinator for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Seminary for Deaf high school students and as the Director of the Teacher Training Program under the Department of Speech and Audiology at the University of Utah, which was established in 1962 (University of Utah, November 28, 1977).

In 1968, Dr. Bitter became an Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. He focused primarily on and dedicated himself to oral education under the Special Education Department. He held this position until 1987, a year after the program closed (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

Throughout his career, Dr. Bitter was involved in projects at both the state and national levels. In 1970, he established the Oral Deaf Association of Utah, and in 1981, he founded the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters. As the chair of the Utah Chapter of the Alexander Graham Bell Association, Dr. Bitter led a group advocating for oral Deaf people (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

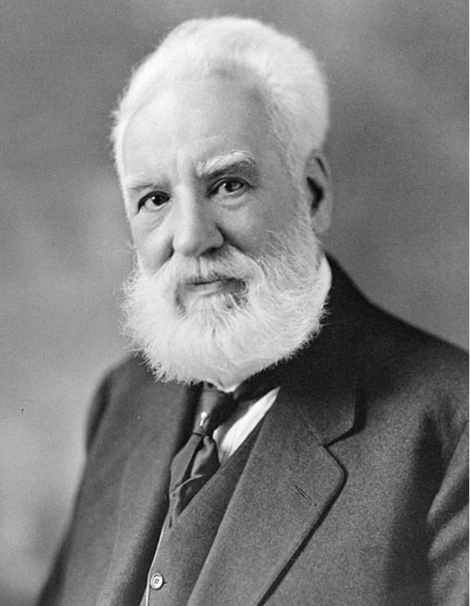

Dr. Bitter was also a prominent lobbyist on Utah Capitol Hill, effectively collaborating with legislators. He continuously emphasized the importance of adequately preparing Deaf and hard of hearing people for life in an English-speaking environment. Dr. Bitter said teaching Deaf people the skills necessary to live a 'normal' life was crucial. His influence in Utah during the 1900s was comparable to that of an early pioneer of oralism, Alexander Graham Bell, who had an impact on deaf education in the United States during the 1800s. Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the full integration of Deaf people into mainstream society was unwavering, and he saw speech as the means to achieve this (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter was also a prominent lobbyist on Utah Capitol Hill, effectively collaborating with legislators. He continuously emphasized the importance of adequately preparing Deaf and hard of hearing people for life in an English-speaking environment. Dr. Bitter said teaching Deaf people the skills necessary to live a 'normal' life was crucial. His influence in Utah during the 1900s was comparable to that of an early pioneer of oralism, Alexander Graham Bell, who had an impact on deaf education in the United States during the 1800s. Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the full integration of Deaf people into mainstream society was unwavering, and he saw speech as the means to achieve this (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's impact on oral deaf education is undeniable. His nationwide public appearances, including workshops for oral interpreters at the University of Cincinnati and the University of Utah, demonstrate his commitment to advancing the field. His leadership roles in the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf (AGB) from 1974 to 1978, including serving as the Governmental Relations Committee chairperson and leading the International Parents' Organization, underscore his influence and impact. His collaboration with the Utah Congressional Team, including Senator Orrin G. Hatch, Chairman of the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee, further demonstrates his reach and influence.

As a parent of nine children, Dr. Bitter's personal life deeply influenced his professional work. His extensive work on several oral education publications, audiovisuals, and videotape products was driven by his desire to improve the lives of Deaf and hard of hearing individuals. The release of his seminal work, 'The Hearing Impaired: New Perspectives in Educational and Social Management,' in 1987 marked a significant milestone in oral deaf education.

As a parent of nine children, Dr. Bitter's personal life deeply influenced his professional work. His extensive work on several oral education publications, audiovisuals, and videotape products was driven by his desire to improve the lives of Deaf and hard of hearing individuals. The release of his seminal work, 'The Hearing Impaired: New Perspectives in Educational and Social Management,' in 1987 marked a significant milestone in oral deaf education.

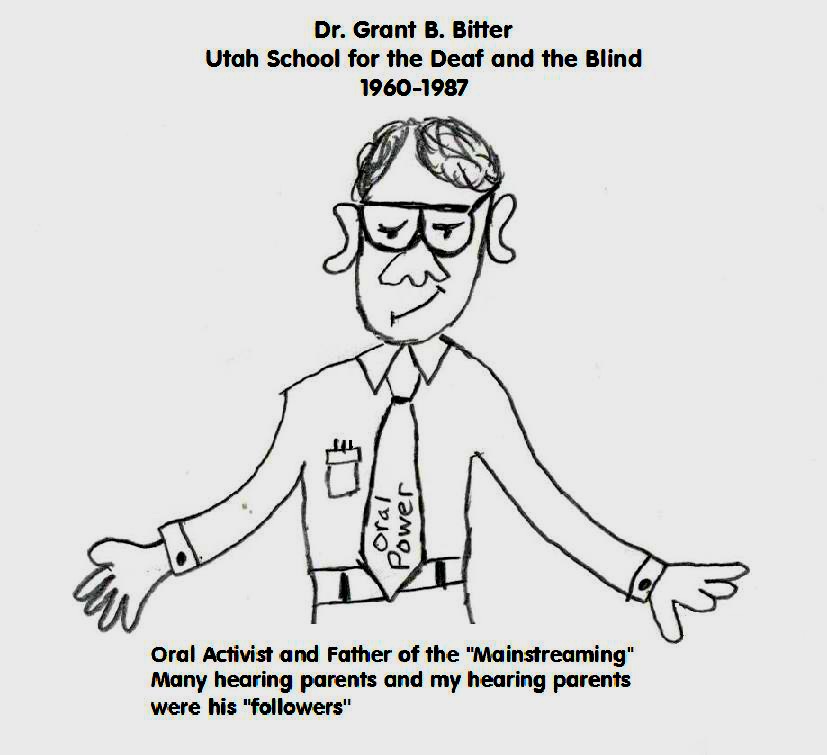

Lisa Richards' Artwork

Features Dr. Grant B. Bitter

Features Dr. Grant B. Bitter

In 2023, Lisa Richards drew the picture above, reflecting on her experiences growing up during the Bitter era and its impact on the deaf educational system in Utah. She is a former student of the Oral Program at the Utah School for the Deaf in the 1960s and 1970s.

A Feud Between Two Giant Figures

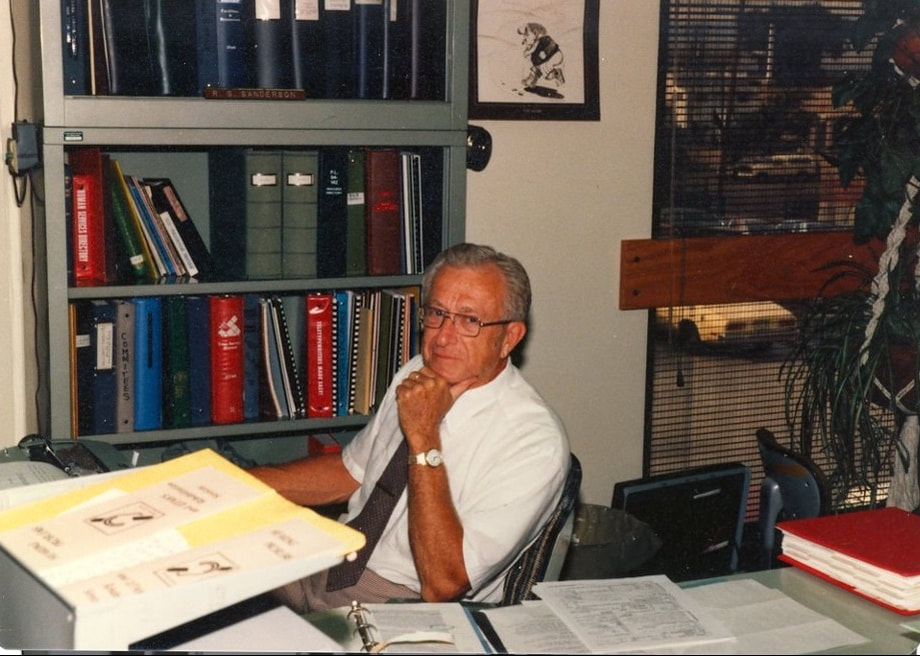

Throughout the 1960s, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a 1936 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf and a 1941 graduate of Gallaudet College, observed a decline in the use of sign language in Utah's educational system as spoken language became more popular across the state. Dr. Sanderson's unwavering determination led to his election as president of the National Association of the Deaf in 1964, after serving as president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963. In 1965, he began working as a Deaf Services counselor, a role that allowed him to directly influence the education and well-being of Deaf children. His courageous fight with Dr. Grant B. Bitter aimed to raise public awareness about sign language preservation and provide high-quality education for Deaf children (Robert G. Sanderson, personal communication, October 2006).

Dr. Sanderson was considered 'gutsy' by the Deaf community, and his fearless personality led him to challenge Dr. Bitter, who had power and influence in the university and legislation promoting the oral approach to deaf education. Hundreds of parents who advocated for oral education also backed Dr. Bitter. Dr. Sanderson's repeated confrontation with Dr. Bitter enraged him and his supporters, leading them to demand Dr. Avaad Rigby, Dr. Sanderson's boss, fire him. Dr. Rigby refused, recognizing the importance of his work. The state recently hired him as a Deaf Services counselor, highlighting his significant value to Utah. Dr. Rigby's support for Dr. Sanderson's numerous political activities outside of work also strengthened their alliance (Robert G. Sanderson, personal communication, October 2006; Stewart, DSDHH Newsletter, April 2012, p. 3). The Bitter-Sanderson conflict also mirrored the historic clash between Dr. Edward Gallaudet, the esteemed president of Gallaudet College, and Alexander Graham Bell in the 1800s. Dr. Gallaudet championed sign language, while Dr. Bell fervently advocated for speech and lip-reading, a conflict that significantly shaped the direction of deaf education.

Dr. Bitter's challenge to the Utah Association for the Deaf was not a random act but a response to what he perceived as a threat to his position. During the interview with the University of Utah in 1987, Dr. Bitter stated that Dr. Sanderson, who became deaf when he was 11 and grew up in both public school and state school for the deaf, 'knew nothing about school programs, but because he was deaf and an advocate of the Deaf community, he obviously played a vital role as far as the Deaf community was concerned' (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987, p. 30). Dr. Sanderson campaigned politically for sign language and was appointed by the Utah State Office of Education, along with other members of the Deaf community, to committees. Dr. Bitter challenged this, particularly Della Loveridge, a legislator and Deaf community advocate who appointed Dr. Sanderson and other Deaf members to her committee while Dr. Bitter was also on it. Dr. Bitter felt threatened by their committee appointments but denied it in his interview. He believed that his objection constituted a threat to them. At a state committee meeting, Della Loveridge described Dr. Bitter as emotionally disturbed. Dr. Bitter thought that the Utah Association for the Deaf had too much freedom in the state office of education, where they held their meetings, and requested that Della Loveridge step down as committee chairperson. This sparked a vendetta against Dr. Bitter (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

Dr. Frank R. Turk, the national director of the Jr. NAD, collaborated with Dr. Sanderson, who was president of the National Association of the Deaf in the 1960s, in a way that contradicted Dr. Bitter's description. He described Dr. Sanderson as an exceptional advocate for education who had a deep understanding of how a Deaf child's K–12 education connects with higher education and eventually leads to desired employment. He strongly advocated for young people with leadership potential and focused on promoting social, educational, economic, and communication equality for Deaf Americans. Dr. Sanderson believed in the importance of socialization in education and advised teachers to encourage students to question their school experience. He urged teachers in public and residential schools to encourage deaf students to ask questions about their school experience. He emphasized that children should learn not only the traditional three R's of reading, writing, and arithmetic but also the importance of socialization. This focus on socialization led to the development of "resourcefulness," which included after-school activities to develop essential life skills such as leadership, empowerment, attitude, discipline, empathy, respect, struggle, humility, initiative, and perseverance. Consequently, the Jr. NAD and SBG organizations were assigned to develop these crucial real-life skills essential for success in school, college, the workplace, career, and community life (Turk, From Oaks to Acorns, 2019).

In a 1982 interview, Dr. Sanderson, a prominent figure in the field of rehabilitation services, who had completed his one-year professorship at Gallaudet College holding the Powrie V. Doctor Chair of Deaf Studies, was asked about his thoughts on total communication and its impact on a child's development. He emphasized the importance of using all available means of communication to help deaf children develop. He stated, "Communication is life. It starts at birth and is a lifelong process. If a baby is suspected to be deaf, I believe that the communication process should begin as soon as the baby can focus his eyes. I would be very concerned that parents understand this. If the process is delayed, a deaf child just cannot catch up—too much is lost. It doesn't matter if the child later learns language or learns how to read lips; he still won't be able to catch up." Dr. Sanderson emphasized that effective communication is more important than the communication method, and many boil down to a lack of clear communication. To ensure a child's optimal learning and development, the focus should be on the quality of communication rather than the specific method. Putting too much emphasis on the mode of communication can very quickly turn off the communication process. He explained that total communication refers to using all available means to communicate ideas when a child is ready. Children differ in readiness, receptivity, tolerance, frustration, and responsiveness. While one child may quickly adapt to speech training, another may become frustrated and unresponsive. Therefore, total communication should consider these individual differences. In his opinion, many schools do not incorporate what is known about the psychology of communication (Kent, The Deaf American, 1982, p. 3). As demonstrated by Dr. Sanderson's thoughts during the interview, his life likely took a dramatic turn when he lost his hearing at eleven. His enrollment at the Utah School for the Deaf, where he learned sign language, probably marked a transformative chapter. He likely realized he had a significant advantage in language development over his born-deaf peers with hearing parents with no language access at home. The school also provided him with full access to education, which was a stark contrast to the limited access he had in a public school after his recovery. This difference in educational opportunities likely fueled his advocacy for Deaf children, highlighting the urgency for them to have access to language and education at residential schools. This challenged Dr. Bitter's mission to promote oralism and mainstream education.

In a 1982 interview, Dr. Sanderson, a prominent figure in the field of rehabilitation services, who had completed his one-year professorship at Gallaudet College holding the Powrie V. Doctor Chair of Deaf Studies, was asked about his thoughts on total communication and its impact on a child's development. He emphasized the importance of using all available means of communication to help deaf children develop. He stated, "Communication is life. It starts at birth and is a lifelong process. If a baby is suspected to be deaf, I believe that the communication process should begin as soon as the baby can focus his eyes. I would be very concerned that parents understand this. If the process is delayed, a deaf child just cannot catch up—too much is lost. It doesn't matter if the child later learns language or learns how to read lips; he still won't be able to catch up." Dr. Sanderson emphasized that effective communication is more important than the communication method, and many boil down to a lack of clear communication. To ensure a child's optimal learning and development, the focus should be on the quality of communication rather than the specific method. Putting too much emphasis on the mode of communication can very quickly turn off the communication process. He explained that total communication refers to using all available means to communicate ideas when a child is ready. Children differ in readiness, receptivity, tolerance, frustration, and responsiveness. While one child may quickly adapt to speech training, another may become frustrated and unresponsive. Therefore, total communication should consider these individual differences. In his opinion, many schools do not incorporate what is known about the psychology of communication (Kent, The Deaf American, 1982, p. 3). As demonstrated by Dr. Sanderson's thoughts during the interview, his life likely took a dramatic turn when he lost his hearing at eleven. His enrollment at the Utah School for the Deaf, where he learned sign language, probably marked a transformative chapter. He likely realized he had a significant advantage in language development over his born-deaf peers with hearing parents with no language access at home. The school also provided him with full access to education, which was a stark contrast to the limited access he had in a public school after his recovery. This difference in educational opportunities likely fueled his advocacy for Deaf children, highlighting the urgency for them to have access to language and education at residential schools. This challenged Dr. Bitter's mission to promote oralism and mainstream education.

During the political dispute between Dr. Sanderson and Dr. Bitter, Hannah P. Lewis, a hearing parent of a grown Deaf son, stated in 1977 that Dr. Sanderson has been a guiding light for the deaf all these years and emphasized the need for his continued support. She said, "I cannot thank him enough for all the help he has given my son throughout his growing-up years." "Thank God for a man like him" (Lewis, Deseret News, November 24, 1977, p. A4). His Ph.D. proved to be a valuable achievement. After completing his Ph.D., he continued to advocate for the Deaf community, leading to the naming of the Deaf Center in his honor in 2003.

Suffice it to say, Dr. Bitter was a prominent figure in Utah's oralism and mainstreaming movement, which has had a significant impact on deaf education in Utah since 1962. As a result of his efforts, the number of students attending Ogden's residential school for Deaf students decreased, and the quality of education also declined. The mainstreaming approach gained popularity but left many alums heartbroken. He also had significant power as a parental figure and used it to push for oralism, making it difficult for the Utah Association for the Deaf to challenge him. When the Teacher Training Program in the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah closed in 1986, he retired in 1987 (Bitter, A Summary Report for Tenure, March 15, 1985). Today, the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah offers a Specialization in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program. While the curriculum does include American Sign Language classes, it still places a greater emphasis on Listening and Spoken Language. This reflects the impact that Dr. Bitter, who passed away in 2000, continues to have on deaf education in Utah. To learn more about the evolving mainstreaming movement, visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective' webpage.

Suffice it to say, Dr. Bitter was a prominent figure in Utah's oralism and mainstreaming movement, which has had a significant impact on deaf education in Utah since 1962. As a result of his efforts, the number of students attending Ogden's residential school for Deaf students decreased, and the quality of education also declined. The mainstreaming approach gained popularity but left many alums heartbroken. He also had significant power as a parental figure and used it to push for oralism, making it difficult for the Utah Association for the Deaf to challenge him. When the Teacher Training Program in the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah closed in 1986, he retired in 1987 (Bitter, A Summary Report for Tenure, March 15, 1985). Today, the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah offers a Specialization in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program. While the curriculum does include American Sign Language classes, it still places a greater emphasis on Listening and Spoken Language. This reflects the impact that Dr. Bitter, who passed away in 2000, continues to have on deaf education in Utah. To learn more about the evolving mainstreaming movement, visit the 'Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Mainstreaming Perspective' webpage.

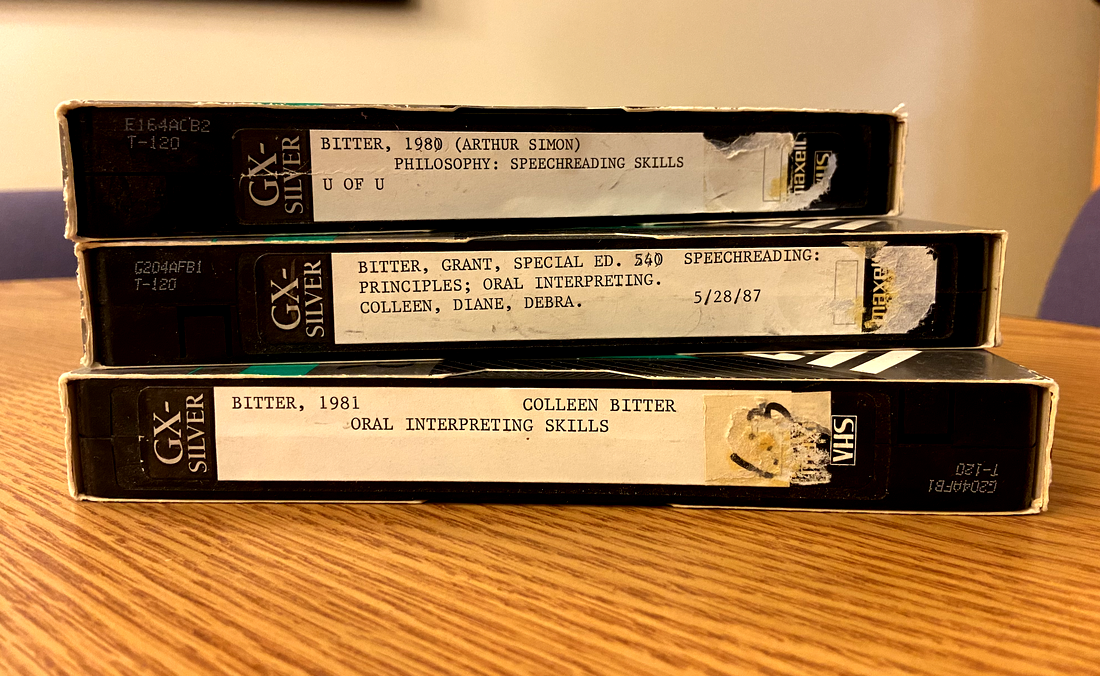

A Collection of

Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Videos

When my colleague, Julie Hesterman Smith, an interpreter, and I were cleaning out an old cabinet at work, we were thrilled to discover the videos made by Dr. Grant B. Bitter during my study of him and his impact on deaf education in Utah. I would like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to our interpreters, especially Julie, who put a lot of effort into captioning the videos. In 2011, they spent numerous hours listening to the recordings and creating caption transcripts. Regrettably, Julie's computer crash resulted in the loss of the transcripts, necessitating a fresh start. She remained committed and completed the transcripts. In 2012, we uploaded the videos to YouTube. Thanks to her dedication, we can watch Dr. Bitter's videos and the oral panelists, including his daughter Colleen. We did our best to caption the video accurately; however, the low quality and difficulty understanding some panel members may have caused some errors. We appreciate the panelists' contributions and have made every effort to represent their words accurately.

We hope you enjoy watching the videos!

Jodi Becker Kinner & Julie Hesterman Smith

We hope you enjoy watching the videos!

Jodi Becker Kinner & Julie Hesterman Smith

Includes interviews conducted by oral deaf education advocate and U of U instructor, Dr. Bitter with Arthur Simon, Sue DeHaan, Elaine. Includes questions about each individual's educational background.

Provides perspectives from deaf individuals who primarily communicate through speech and speech reading on situations when they would utilize an interpreter or other supports i.e. note taker. Dr. Bitter moderates the discussion at the University of Utah in 1983.

This video was filmed in Dr. Grant Bitter's Special Education 540 class, in May 1987. There is a panel of deaf individuals discussing their preferences regarding speech reading and oral interpreting.

This video was recorded in May 1987 at the University of Utah in ED 540. Instructor Dr. Grant Bitter facilitates a panel of deaf adults discussing their educational background, speech reading, and preferences regarding oral interpreters.

This video was recorded in May 1987 at the University of Utah in ED 540. Instructor Dr. Grant Bitter facilitates a panel of deaf adults discussing their educational background, speech reading, and preferences regarding oral interpreters.