The Controversial Parallel Correspondence

Between American Sign Language

and Listening & Spoken Language

Between American Sign Language

and Listening & Spoken Language

Compiled & Written by Jodi Becker Kinner

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Edited by Bronwyn O'Hara

Co-Edited by Valerie G. Kinney

Published in 2016

Updated in 2024

Author's Note

As a parent of two Deaf children, my passion for deaf education comes from my personal journey. My father-in-law, Kenneth L. Kinner, also sparked my interest and shared with me the history of deaf education in Utah, including its oral and mainstreaming impact. This inspired me to meticulously document the controversial events of that era. If it weren't for him, I wouldn't be able to advocate for my kids without knowing the history. My studies at the Gallaudet School Social Work Program further deepened my understanding of the complexities of education, legislation, and policy. Moreover, my role on the Institutional Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind has truly empowered me to advocate for my children and others in Utah who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled. This platform has given me the strength and voice to make a difference.

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

As shown in the picture, Lisa Richards, born in 1959, was practicing her speech in the oral program at Lafayette Elementary School, one of the Extension Division programs established in 1959 to encourage mainstreaming in Utah. You can click her name to watch the video of her experience growing up in the Oral Program through the Extension Program of the Utah School for the Deaf.

As someone who is passionate about deaf education in Utah, I have personally witnessed the inequality in the deaf education system. Unfortunately, the Utah School for the Deaf has been known to favor and promote oral education, which has caused numerous conflicts between the oral and sign language departments in the dual-track and two-track programs. I have been working on Utah Deaf History for some time now. During this process, I and other ASL/English bilingual supporters found ourselves battling with Steven W. Noyce, the superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, who was a staunch advocate for the oral movement. In 2011, I discovered a controversial parallel between American Sign Language and Listening and Spoken Language between 1962 and 2011. This webpage outlines the startling discovery in detail.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

The Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind is a state school that promotes inclusivity by serving a diverse student population of Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Blind, Low Vision, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals. When we discuss deaf education, we will primarily refer to the 'Utah School for the Deaf.' On the other hand, when we talk about the entire state school, we will use the term "Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind."

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Utah School for the Deaf underwent significant changes. The dual-track program and the two-track program, divided into an oral department and a sign language department, significantly impacted the lives of Deaf students and their families. To avoid confusion, we refer to the "dual-track program" from the 1960s and the "two-track program" from the 1970s on our education webpages. These programs will help us understand how these changes have affected students, teachers, administrators, and the Utah Association for the Deaf.

The "Deaf Education in Utah" webpages contain repetitive and overlapping sections, similar to those on other education webpages. The introductions to each section are also similar, and they will directly get to the point of the webpage's topic.

When writing about individuals for our history website, I choose to use their first name to acknowledge all individuals who contribute to and advocate for our community's causes. Our patriarchal culture often expects to recognize women's advocacy, contributions, and achievements using their husbands' last names instead of their own. However, in the spirit of inclusivity, equality, and recognizing each individual's unique identity, I have decided to use their first names throughout the website. This decision reaffirms our commitment to these values and highlights the significant role of women's advocacy in our community.

Our organization, previously known as the Utah Association for the Deaf, changed its name to the Utah Association of the Deaf in 2012. The association was known as the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1962. The association changed its name to the Utah Association for the Deaf in 1963. Finally, in 2012, the association reverted to its previous name, the Utah Association of the Deaf. When writing the history website, I use both "of" and "for" to reflect the different eras of the association's history.

As shown in the picture, Lisa Richards, born in 1959, was practicing her speech in the oral program at Lafayette Elementary School, one of the Extension Division programs established in 1959 to encourage mainstreaming in Utah. You can click her name to watch the video of her experience growing up in the Oral Program through the Extension Program of the Utah School for the Deaf.

As someone who is passionate about deaf education in Utah, I have personally witnessed the inequality in the deaf education system. Unfortunately, the Utah School for the Deaf has been known to favor and promote oral education, which has caused numerous conflicts between the oral and sign language departments in the dual-track and two-track programs. I have been working on Utah Deaf History for some time now. During this process, I and other ASL/English bilingual supporters found ourselves battling with Steven W. Noyce, the superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, who was a staunch advocate for the oral movement. In 2011, I discovered a controversial parallel between American Sign Language and Listening and Spoken Language between 1962 and 2011. This webpage outlines the startling discovery in detail.

Thank you for your interest in the 'Deaf Education History in Utah' webpage of this website. Your engagement is invaluable to our mission to educate and advocate for the Deaf community and its history in Utah.

Enjoy!

Jodi Becker Kinner

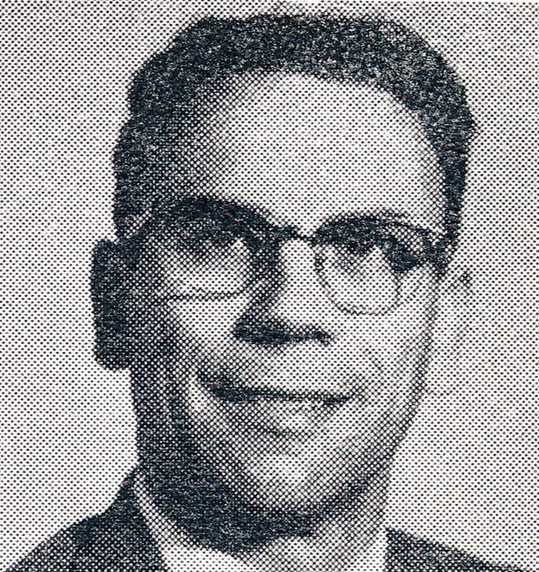

Dr. Grant B. Bitter,

the Father of Mainstreaming

the Father of Mainstreaming

Under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a firm advocate for oral and mainstream education, Utah's groundbreaking movement to mainstream all Deaf children began in the 1960s. Dr. Bitter's efforts earned him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' This movement was in stark contrast to the historical significance of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, the country's first female state senator and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind, who in 1896 spearheaded a proposal for the 'Act Providing for Compulsory Education of Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Citizens,' which made attendance at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind mandatory (Martha Hughes Cannon, Wikipedia, April 20, 2024). Her legislation led to its successful passage in 1896 and marked a turning point in the education of Deaf and Blind children. However, Dr. Bitter advocated for mainstreaming all Deaf children, paving the way for widespread acceptance of this approach in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

His daughter, Colleen, was born deaf in 1954, which was another reason for his dedication to the advancement of both oral and mainstream education. Dr. Bitter supported the idea of mainstreaming for all Deaf and hard of hearing children for two main reasons: his own Deaf daughter and his internship experience at the Lexington School for the Deaf. During his master's degree studies, he interned at Lexington School for the Deaf, an oral school, and was shocked to see young children having to leave their parents for a week, often crying and screaming. His role as a father of a Deaf child, as well as his experience, inspired him to advocate for mainstreaming, allowing Deaf children to attend local public schools at home (Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987).

In the 1970s, Dr. Stephen C. Baldwin, a Deaf educator who served as the Total Communication Division Curriculum Coordinator at the Utah School for the Deaf, shared his observations of Dr. Bitter. Dr. Bitter, a firm advocate of oral and mainstream philosophy, was particularly vocal about his beliefs. His influence, as Dr. Baldwin noted, was profound. Dr. Bitter was a hard-core oralist and one of the top figures in oral education, and no one was more persistent than him in promoting an oral and mainstream approach. Dr. Baldwin also recalled how Dr. Bitter criticized the popular use of sign language, arguing that it hindered the development of oral skills and enrollment in residential settings, which he believed isolated Deaf individuals from mainstream society (Baldwin, 1990).

Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. This included disputes during oral demonstrations, protests, education committee meetings, and board meetings. Dr. Bitter, who opposed anyone who stood in the way of his goals of promoting oral and mainstream education, has formally requested the job removal of Dr. Robert Sanderson and Dr. Jay J. Campbell, both respected advocates for sign language. He believed they were interfering with his mission. Additionally, he expressed dissatisfaction with Beth Ann Stewart Campbell's television interpretation of news in sign language, feeling it did not align with his educational goals. He also asked Della L. Loveridge, a Utah legislator and respected committee chairperson, to resign because she invited representatives from the Utah Association for the Deaf, which he saw as a shift from the committee's focus. The Utah Association for the Deaf, in the face of Dr. Bitter's opposition, demonstrated remarkable resilience, marking a significant turning point in their history and inspiring others with their strength and determination.

Dr. Bitter has had an extensive career in teaching and curriculum development. His journey began at the Extension Division of the Utah School for the Deaf in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked as a teacher and curriculum coordinator. His passion for education led him to become a director and professor in the Teacher Training Program, where he focused primarily on oral education under the Department of Special Education at the University of Utah. Dr. Bitter also served as the coordinator of the Deaf Seminary Program under The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

Dr. Bitter believed strongly in oralism, which is the belief that Deaf individuals should learn to speak. He was so committed to this idea that he included it in his teaching methods for the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah. To support this cause, he founded the Oral Deaf Association of Utah (ODAU) in 1970 and the Utah Registry of Oral Interpreters in 1981 (Bitter, Summary Report for Tenure, 1985; Bitter, Utah's Hearing-Impaired Children... At High Risk, 1986).

The Implementation of the Dual-Track Program,

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

Commonly Known as "Y" System

at the Utah School for the Deaf

In the fall of 1962, the Utah Deaf community was surprised by the revolutionary changes at the Utah School for the Deaf, which introduced the dual-track program, also commonly known as the "Y" system. The unexpected change had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children, evoking a sense of empathy within the community. The Utah Association of the Deaf, which advocated for sign language, was unaware that the Utah Council for the Deaf had spearheaded the change, advocating for speech-based instruction and successfully pushing for its implementation at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962). It is believed that Dr. Bitter was a member of this council. The dual-track program provided an oral program in one department and a simultaneous communication program in another department, which was later replaced by a combined system. However, the dual-track policy mandated that all Deaf children begin with the oral program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Gannon, 1981). The Utah State Board of Education, a key player in educational policy, approved this policy reform on June 14, 1962, with endorsement from the Special Study Committee on Deaf Education (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). The newly hired superintendent, Robert W. Tegeder, accepted the parents' proposals and initiated changes to the school system (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter, 1962; Grant Bitter: Everett L. Cooley Oral History Project, March 17, 1987). This new program not only affected the lives of Deaf children but also their families.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

The "Y" system, part of the dual-track program, imposed significant restrictions and challenges on students and their families. This system separated learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). The "Y" system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. The school's preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Dr. Grant B. Bitter's Paper, 1970s; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The placement of transferred students in the signing program labeled them as "oral failures" (The UAD Bulletin, Spring 1965). There was a discussion about the age at which students can transfer to a simultaneous communication program. According to the "First Reunion of the Utah School for the Deaf Alumni Program Book, 1976," this would be when they were 10–12 years old or entered sixth grade. However, according to the Utah Eagle's February 1968 issue, students must remain in the oral program for the first six years of school, which may be in the 6th or 7th grade. So, I am using between the 6th and 7th grades, rather than based on their age. Their birth date, progression, and other factors could determine their placement.

As a result of the "Y" system's implementation, the Utah School for the Deaf had to undergo significant changes. The school had to hire more oral teachers and establish speech as the primary mode of communication, shifting the focus of the learning environment. The dual-track program initially placed all elementary school students in the oral department, transferring them to the simultaneous communication department only if they failed in the oral program. This approach was based on the belief that early development of oral skills was crucial for Deaf students, with sign language learning considered a secondary focus. The change in focus and the increased hiring of oral teachers had a significant impact on the school's learning environment, altering its dynamics and atmosphere (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Deanne Kinner Montgomery, personal communication, May 4, 2024).

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, some changes were made at the Utah School for the Deaf without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were surprised to find out about the changes. These changes caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy.

The dual-track program shifted its approach for prospective teachers from sign language to the oral method, prioritizing speech as the primary mode of communication for Deaf students in classrooms. The administrators at the Utah School for the Deaf considered the dual-track program to be more advantageous than a single-track system (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). According to them, the oral program required a "pure oral mindset." In 1968, the Utah School for the Deaf was one of the few residential schools in the country to offer an exclusively oral program for elementary students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). By 1973, the Utah School for the Deaf was the only school in the United States that provided parents and Deaf students with both methods of communication through the dual-track system (Laflamme, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, 1973).

On June 14, 1962, the Utah State Board of Education approved the dual-track program, which led to the division of the Ogden campus into two parts during the summer break (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 14, 1962). The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The school prohibited interaction between oral and sign language students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968; Wight, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 19, 1970). However, due to low student enrollment in competitive sports, the athletic program combined both departments. The team had oral and sign language coaches to communicate with their respective students (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This unique situation highlights the challenges and complexities of implementing the dual-track program.

During the 1962–63 school year, some changes were made at the Utah School for the Deaf without informing the Deaf students. When the students arrived at school in August, they were surprised to find out about the changes. These changes caused a lot of anger among older students, as well as many disagreements between veteran teachers and the Utah Deaf community. Barbara Schell Bass, a long-serving Deaf teacher at the Utah School for the Deaf, said that the students' physical and methodological separation had painful consequences. Many teachers lost their friendships due to philosophical disagreements, classmates isolated themselves from each other, and administrators struggled to divide their loyalties (Bass, 1982).

The dual-track program's "Y" segregation system, which separated oral and sign language students, caused dissatisfaction and led to protests. High school students raised concerns about this system, but the school administration dismissed their objections. In 1962 and 1969, the students went on strike to oppose the new dual-track policy because they felt it created a "wall" that prevented oral and sign language students from interacting with each other. Despite the students' outcry, the school administration continued the dual-track policy.

Following the 1962 protest against social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus, Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a steadfast advocate for oral and mainstream education, and his oral supporters suspected that the Utah Association of the Deaf had organized the student strike. The Utah State Board of Education conducted an investigation but found no evidence of any connection between the students and the Utah Association for the Deaf (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963; Kenneth L. Kinner, personal communication, May 14, 2011). In the face of societal segregation, the simultaneous communication students demonstrated their unwavering determination and courage by staging their own protests.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, who served as the president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1960 to 1963, denied any involvement in a strike during his tenure. He maintained that the strike was a spontaneous reaction by students who felt that the conditions, restrictions, and personalities at the Utah School for the Deaf had become intolerable (Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963). In the Fall-Winter 1962 issue of the UAD Bulletin, the Utah Association of the Deaf expressed its support for a classroom test of the dual-track program at the Utah School for the Deaf. However, they openly opposed complete social isolation, interference with religious activities, crippling the sports program, and intense pressure on children in the oral program to comply with the "no signing" rule (UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2). The dual-track program's implementation marked a dark chapter in the history of deaf education in Utah.

The Oral Education Impacts

the Utah School for the Deaf

the Utah School for the Deaf

In 1962, the University of Utah established an oral training program within the Special Education Department as part of the implementation of the dual-track program. This program was utilized by the Utah School for the Deaf to expand its oral program (The Utah Eagle, February 1968). This program, often referred to as an 'army of oral teachers,' provided employment opportunities at the school. The oral program also extended to Ogden's residential campus and all extension classrooms. The surplus of orally trained teachers led to a shift from sign language to non-academic training, unsettling deaf education professionals and families who advocated sign language.

The Utah School for the Deaf fully embraced the oral education philosophy and teaching approach, emphasizing the importance of early speaking and listening exposure for children's effective communication and listening skills. In 1963, the Conference of Executives of American Schools for the Deaf commended the University of Utah's Oral Deaf Education Department (Survey of Program for Preparation of Teachers of the Deaf at the University of Utah, 1963). This recognition occurred during the era of oral dominance in deaf education in Utah and nationwide.

The Utah School for the Deaf fully embraced the oral education philosophy and teaching approach, emphasizing the importance of early speaking and listening exposure for children's effective communication and listening skills. In 1963, the Conference of Executives of American Schools for the Deaf commended the University of Utah's Oral Deaf Education Department (Survey of Program for Preparation of Teachers of the Deaf at the University of Utah, 1963). This recognition occurred during the era of oral dominance in deaf education in Utah and nationwide.

Attack on a Different Front

In October 1962, parents who supported sign language informed the Utah Association of the Deaf (UAD) about a letter that advocated and endorsed the implementation of oral education at the Utah School for the Deaf. The letter was addressed to parents of Utah's Deaf children enrolled in the Oral Program of the Utah School for the Deaf and its extension classrooms. The UAD published the entire letter on page 3 of the UAD Bulletin for Fall-Winter 1962. It is quoted below. There is no way to determine who wrote the 'Open Letter' to parents or who served on this council.

UTAH COUNCIL FOR THE DEAF

Dear Parents,

After several years of work, the Utah School for the Deaf finally inaugurated this year a dual program which gives parents a choice as to the type of education their children are to receive at the school. For the first time, parents who chose the oral program have found their children in an oral environment not only in the classrooms but in the dormitories, playgrounds, and dining rooms.

The staff has made a sincere effort to encourage oral communication at all times.

As a parent who has indicated an interest in having your child receive a strong oral program, we are sure that you are alarmed at recent events which have transpired at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden.

It is apparent that certain individuals in the adult deaf groups and some of the older group of students who are long-time trouble-makers in the non-oral department at the school have dedicated themselves to killing this program before it has a chance to prove its merits. To many parents who are somewhat undecided, they have made an aggressive campaign in order to cloud the issues. They make no attempt to hide their plan to foment disunity at the school and press for dismissal of the administrators and some school personnel who are trying to help us with the program. From information we have obtained, it is clear that they intend to make it impossible for Riley School to develop its present program.

If there is a change of administration at the State School, there is serious doubt whether any orally-trained or -inclined replacement teachers would be willing to come into a state where the education of the deaf is in the hands of a few antagonistic deaf alumni and a few disgruntled parents. Through control of hiring replacement teachers, an unsympathetic administration would be able to destroy the program without coming into the open.

After having planned and put into operation the present fine program, we will not willingly nor quietly lose what we have put forth so much effort to accomplish.

The State Board of Education is being subjected to tremendous pressure from the adult Deaf. One board member wants to eliminate or seriously hamper efforts to maintain the oral department at the State School for the Deaf. He has made no secret of his dislike for the day school program in Salt Lake City and any further expansion in oral education.

If we are to save the present oral program, it is imperative that you make your feelings known individually to the following board members:

(Names and addresses of nine board members, plus Dr. Marion G. Merkeley and Dr. Marsden B. Stokes are listed).

It may be necessary for us to appear in person before the board to demand that the adults deaf terminate entirely their efforts to control and administer the education program of our children in the Utah Schools and that the administration be left in the hands of those trained and hired for that job.

Trained oral teachers and administrators will not and cannot remain in our schools when they are subjected to continual harassment, personal attack, and degradation.

Once again, we are fighting for the survival of the present program. Write your letter now!

Sincerely yours,

Utah Council of the Deaf

(The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962)

After several years of work, the Utah School for the Deaf finally inaugurated this year a dual program which gives parents a choice as to the type of education their children are to receive at the school. For the first time, parents who chose the oral program have found their children in an oral environment not only in the classrooms but in the dormitories, playgrounds, and dining rooms.

The staff has made a sincere effort to encourage oral communication at all times.

As a parent who has indicated an interest in having your child receive a strong oral program, we are sure that you are alarmed at recent events which have transpired at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden.

It is apparent that certain individuals in the adult deaf groups and some of the older group of students who are long-time trouble-makers in the non-oral department at the school have dedicated themselves to killing this program before it has a chance to prove its merits. To many parents who are somewhat undecided, they have made an aggressive campaign in order to cloud the issues. They make no attempt to hide their plan to foment disunity at the school and press for dismissal of the administrators and some school personnel who are trying to help us with the program. From information we have obtained, it is clear that they intend to make it impossible for Riley School to develop its present program.

If there is a change of administration at the State School, there is serious doubt whether any orally-trained or -inclined replacement teachers would be willing to come into a state where the education of the deaf is in the hands of a few antagonistic deaf alumni and a few disgruntled parents. Through control of hiring replacement teachers, an unsympathetic administration would be able to destroy the program without coming into the open.

After having planned and put into operation the present fine program, we will not willingly nor quietly lose what we have put forth so much effort to accomplish.

The State Board of Education is being subjected to tremendous pressure from the adult Deaf. One board member wants to eliminate or seriously hamper efforts to maintain the oral department at the State School for the Deaf. He has made no secret of his dislike for the day school program in Salt Lake City and any further expansion in oral education.

If we are to save the present oral program, it is imperative that you make your feelings known individually to the following board members:

(Names and addresses of nine board members, plus Dr. Marion G. Merkeley and Dr. Marsden B. Stokes are listed).

It may be necessary for us to appear in person before the board to demand that the adults deaf terminate entirely their efforts to control and administer the education program of our children in the Utah Schools and that the administration be left in the hands of those trained and hired for that job.

Trained oral teachers and administrators will not and cannot remain in our schools when they are subjected to continual harassment, personal attack, and degradation.

Once again, we are fighting for the survival of the present program. Write your letter now!

Sincerely yours,

Utah Council of the Deaf

(The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962)

The Utah Association of the Deaf

Responds to the Utah Council for the Deaf

Responds to the Utah Council for the Deaf

The Utah Association of the Deaf expressed concern about the letter published by the Utah Council for the Deaf, fearing it could harm the Utah School for the Deaf, its administrators, teachers, students, and Deaf adults. Since the Utah State Board of Education and the State Superintendent of Public Instruction both received copies of the letter, the UAD decided it was unnecessary to dispute it. However, to reassure some parents and set the record straight, the UAD responded to the Utah Council for the Deaf's Open Letter by publishing an article titled "Who's For the Deaf?" in the same issue of The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, which is summarized here. This article provided a Deaf perspective in response to the Council's Open Letter. Given that they had firsthand experience in the deaf school system, Council members may better understand UAD viewpoints on the subject.

According to the UAD, the Utah Council of the Deaf was unable to comprehend the reality of living with hearing loss. There were no Deaf members on the Council who might provide helpful comments on Deaf perspectives and experiences. The Council set goals for all Deaf people, young and old. The UAD believed the Council's formation solely served to discredit and disparage any educational ideas that deviated from the Council's viewpoints.

The Utah Association of the Deaf emphasized that as an organization representing Deaf and hard of hearing adults, it supported a fair assessment of the Utah School for the Deaf's dual program. This involved allowing the oral/aural program to be evaluated.

The UAD criticized the strict prohibition of signing in front of the oral students, which led to the complete isolation of these students. This segregation also affected religious activities, hindered athletic programs, and placed significant pressure on students in the Oral Program not to use sign language inside or outside the classroom. The Utah Council of the Deaf labeled Deaf students who opposed the segregated environment as "trouble-makers," which the UAD found to be insensitive and disrespectful.

The UAD refuted the accusation that Deaf adults were aggressively trying to conceal the issue. According to the UAD, Deaf adults with college degrees offered advice to parents who were struggling to fully comprehend the consequences of their decisions about their children's education.

It was defamatory for the Utah Council of the Deaf to refer to the Deaf community as "antagonistic" and hearing parents who disagreed as "disgruntled." Why did they identify individuals who disagreed with them negatively? It seemed like they didn't care about the viewpoints of the Utah Association of the Deaf, the Deaf community, or signing parents. They showed no interest in collaborating to find solutions.

The UAD's claim of an attack on Riley Elementary School's oral day school program was unexpected and false. The Utah Association of the Deaf clarified that the UAD did not oppose the Riley School Deaf Day program or any other deaf school that adequately trains deaf education teachers. The UAD opposed any deaf day school lacking proper staff, grade advancement, vocational training opportunities, and social activities. They expressed concerns about several oral programs in Utah day schools with untrained employees and hoped it wouldn't happen at Riley. The Utah Council for the Deaf misinterpreted this warning as a call to end Riley School's Oral Program, which was a twisted fact. The UAD did not threaten the school's oral program.

The Council expressed that "trained oral teachers and administrators will not and cannot remain in our schools when they are subject to constant harassment, personal attack, and degradation." The UAD was aware of a few sign language teachers who had been persecuted but not of any oral language teachers. In response to the Council's authoritarian paragraph, the UAD instructed parents to "demand that the deaf adults terminate entirely their efforts to control and administer our children's education program." Their response reflects the 54 years the UAD policy has been in place. Deaf students in their schools need the best possible education to become self-sufficient and valued community members. The UAD believed it was their responsibility and right as citizens to educate the public about deaf concerns and provide progressive information on deaf education. The UAD did not want students who graduated from Utah schools to become welfare recipients. Deaf adults in the community recognized the potential for better outcomes for young deaf people. They were eager to share their observations with the State Office of Education and the Utah School for the Deaf.

The Utah Association of the Deaf agreed with the Council that the State Board of Education supervised and administered the deaf educational program at the Utah School for the Deaf. Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder was in charge of implementing it, and Deaf people did not control or run the educational program assumed by the Utah Council for the Deaf (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2–3).

According to the UAD, the Utah Council of the Deaf was unable to comprehend the reality of living with hearing loss. There were no Deaf members on the Council who might provide helpful comments on Deaf perspectives and experiences. The Council set goals for all Deaf people, young and old. The UAD believed the Council's formation solely served to discredit and disparage any educational ideas that deviated from the Council's viewpoints.

The Utah Association of the Deaf emphasized that as an organization representing Deaf and hard of hearing adults, it supported a fair assessment of the Utah School for the Deaf's dual program. This involved allowing the oral/aural program to be evaluated.

The UAD criticized the strict prohibition of signing in front of the oral students, which led to the complete isolation of these students. This segregation also affected religious activities, hindered athletic programs, and placed significant pressure on students in the Oral Program not to use sign language inside or outside the classroom. The Utah Council of the Deaf labeled Deaf students who opposed the segregated environment as "trouble-makers," which the UAD found to be insensitive and disrespectful.

The UAD refuted the accusation that Deaf adults were aggressively trying to conceal the issue. According to the UAD, Deaf adults with college degrees offered advice to parents who were struggling to fully comprehend the consequences of their decisions about their children's education.

It was defamatory for the Utah Council of the Deaf to refer to the Deaf community as "antagonistic" and hearing parents who disagreed as "disgruntled." Why did they identify individuals who disagreed with them negatively? It seemed like they didn't care about the viewpoints of the Utah Association of the Deaf, the Deaf community, or signing parents. They showed no interest in collaborating to find solutions.

The UAD's claim of an attack on Riley Elementary School's oral day school program was unexpected and false. The Utah Association of the Deaf clarified that the UAD did not oppose the Riley School Deaf Day program or any other deaf school that adequately trains deaf education teachers. The UAD opposed any deaf day school lacking proper staff, grade advancement, vocational training opportunities, and social activities. They expressed concerns about several oral programs in Utah day schools with untrained employees and hoped it wouldn't happen at Riley. The Utah Council for the Deaf misinterpreted this warning as a call to end Riley School's Oral Program, which was a twisted fact. The UAD did not threaten the school's oral program.

The Council expressed that "trained oral teachers and administrators will not and cannot remain in our schools when they are subject to constant harassment, personal attack, and degradation." The UAD was aware of a few sign language teachers who had been persecuted but not of any oral language teachers. In response to the Council's authoritarian paragraph, the UAD instructed parents to "demand that the deaf adults terminate entirely their efforts to control and administer our children's education program." Their response reflects the 54 years the UAD policy has been in place. Deaf students in their schools need the best possible education to become self-sufficient and valued community members. The UAD believed it was their responsibility and right as citizens to educate the public about deaf concerns and provide progressive information on deaf education. The UAD did not want students who graduated from Utah schools to become welfare recipients. Deaf adults in the community recognized the potential for better outcomes for young deaf people. They were eager to share their observations with the State Office of Education and the Utah School for the Deaf.

The Utah Association of the Deaf agreed with the Council that the State Board of Education supervised and administered the deaf educational program at the Utah School for the Deaf. Superintendent Robert W. Tegeder was in charge of implementing it, and Deaf people did not control or run the educational program assumed by the Utah Council for the Deaf (The UAD Bulletin, Fall-Winter 1962, p. 2–3).

An Oral Advocate Parent Wrote a Letter to the Utah Association for the Deaf President Robert G. Sanderson

Despite the Utah Association for the Deaf's response in the fall-winter of 1962, which clarified the Utah Council for the Deaf's Open Letter and its harmful to the Utah School for the Deaf and the Utah Deaf community, one parent remained misinformed. On April 25, 1963, D'On Reese, the parent of a Deaf son named Norman, enrolled in the Oral Program at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah. She believed that the Utah Association for the Deaf was still attempting to destroy oralism. She expressed her views in a letter to Robert G. Sanderson, President of the Utah Association of the Deaf. The UAD Bulletin published her letter and Robert's response during the summer of 1963. The letters are listed below.

Dear Mr. Sanderson:

I really enjoy reading your UAD Bulletin. I’ve never seen so much nonsense put together. It really makes for funny reading.

Why don’t you put your time to good use, instead of just trying to find ways of get rid of oralism?

I have a son in the oral department of the Utah School for the Deaf. And I have not heard one parent that has a child in that school say anything against oralism. It’s just you adult Deaf.

I don’t know what satisfaction it gives you to try to stop oralism. As long as I’m alive, (I’m a lot younger than you) you’ll have me to fight, if you expect to get rid of oralism.

The only time that I feel bad about my son being deaf is for fear he might meet up with ignorant people like you.

When you wrote to Dr. Greenaway at the Yorkshire School for the Deaf, did you inform him that the parents at our school are perfectly satisfied with what they have?

Did you tell him that it’s just you meddling outsiders, that are afraid that our children might be getting something better than you did, that are upset?

Did you tell him that you went to the school board members last fall and tried to stop our oral program?

Did you tell him that you got ahold of our students last fall and staged a walk -out to get rid of oralism?

Did you tell him that you circulated a letter to our legislators to try and get our budget for the school cut so that we can’t have qualified teachers?

Where has all of this gotten you?

Our oral department is still there and I think it will be there after you’re long gone.

Do you see us oral parents going around trying to chop your fingers off so you can’t sign?

I’m perfectly willing to let the simultaneous dept. stay at our school.

Those people who are too lazy to learn to talk need it.

We’re not bothering you so why don’t you leave us alone?

We are the ones that brought these deaf children into the world. We are the ones who have stayed awake at nights trying to decide what’s best for them. We’ve looked at both sides of the ways to teach our children and we have come to the conclusion that oralism is best.

Are you willing for me to tell you how to educate your hearing children?

According to you I have every right to because I can hear and you can’t.

We have a wonderful administration at our school and very good teachers. Now if you’ll just leave them and our children alone, we’ll be most grateful.

When we need your help, we’ll ask for it.

Sincerely yours,

D’On Reese

Smithfield, R.F.D. #1 Utah

(The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963, p. 2 & 14)

I really enjoy reading your UAD Bulletin. I’ve never seen so much nonsense put together. It really makes for funny reading.

Why don’t you put your time to good use, instead of just trying to find ways of get rid of oralism?

I have a son in the oral department of the Utah School for the Deaf. And I have not heard one parent that has a child in that school say anything against oralism. It’s just you adult Deaf.

I don’t know what satisfaction it gives you to try to stop oralism. As long as I’m alive, (I’m a lot younger than you) you’ll have me to fight, if you expect to get rid of oralism.

The only time that I feel bad about my son being deaf is for fear he might meet up with ignorant people like you.

When you wrote to Dr. Greenaway at the Yorkshire School for the Deaf, did you inform him that the parents at our school are perfectly satisfied with what they have?

Did you tell him that it’s just you meddling outsiders, that are afraid that our children might be getting something better than you did, that are upset?

Did you tell him that you went to the school board members last fall and tried to stop our oral program?

Did you tell him that you got ahold of our students last fall and staged a walk -out to get rid of oralism?

Did you tell him that you circulated a letter to our legislators to try and get our budget for the school cut so that we can’t have qualified teachers?

Where has all of this gotten you?

Our oral department is still there and I think it will be there after you’re long gone.

Do you see us oral parents going around trying to chop your fingers off so you can’t sign?

I’m perfectly willing to let the simultaneous dept. stay at our school.

Those people who are too lazy to learn to talk need it.

We’re not bothering you so why don’t you leave us alone?

We are the ones that brought these deaf children into the world. We are the ones who have stayed awake at nights trying to decide what’s best for them. We’ve looked at both sides of the ways to teach our children and we have come to the conclusion that oralism is best.

Are you willing for me to tell you how to educate your hearing children?

According to you I have every right to because I can hear and you can’t.

We have a wonderful administration at our school and very good teachers. Now if you’ll just leave them and our children alone, we’ll be most grateful.

When we need your help, we’ll ask for it.

Sincerely yours,

D’On Reese

Smithfield, R.F.D. #1 Utah

(The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963, p. 2 & 14)

Utah Association for the Deaf President

Robert G. Sanderson Responds to a Parent’s Letter

Robert G. Sanderson Responds to a Parent’s Letter

Dear Mrs. Reese:

Thank you very much for your letter of April 25. As you requested, we shall publish it in full, verbatim.

The UAD welcomes expressions of opinions from parents, teachers, professional educators, and individuals of every philosophy. The pages of the UAD Bulletin are always open to those who wish to be heard.

Membership in the Association entitles one to attend meetings, propose and discuss policies and actions. Where a majority of the membership does not agree with the policies and actions of the officers, they may exercise the American right of “voting them out” at regularly scheduled elections. We would welcome your attendance at our forthcoming convention and would give you and any other parent an opportunity to be heard at the proper time and in proper order; the same privileges are extended to all registered members.

Contrary to the belief of oralists that the adult deaf oppose oral instruction, we certainly do not. It has its place in the curriculum, for those who can benefit from it, along with reading, writing, arithmetic, history, geography, science, and all of the other subjects a school must teach. What the adult deaf do oppose is disproportionate attention to speech and lip-reading aspects, to the extent that the assimilation of subject matter becomes so difficult and so delayed that the total education of the deaf child suffers.

We adult deaf are interested in seeing deaf children acquire the best possible education as well as seeing them learn to speak. As we have learned in our personal lives, covering in the aggregate hundreds of years of experience in coping with the multitudinous socio-economic problems of deafness on a day-to-day basis, speech and lip-reading, while useful, solve no basic problems. The quality and the amount of education received, academically and vocationally, are what count.

I sincerely hope that your deaf son can profit by total oralism. Some children can and some cannot and any professional educator, if he is honest, will tell you so. If it should become apparent to you that your boy’s progress is not what it should be or what you expect or that his happiness (which is so close to your heart) is at stake, then perhaps your love for him would suggest another approach – one that guarantees to him an immediate means of expressing himself. The satisfaction of early and full self expression cannot be overestimated in its value to a well-adjusted child.

It should be remembered that we deaf adults had parents, many of whom once felt as you do, so we understand and appreciate your position.

Where the official position of the Association is concerned, I would suggest that you ascertain the facts with reference to other matters you mention in your letter. However, any member of our association, regardless of his office, may act individually as his conscience so dictates since he is also a taxpayer with those certain rights and privileges we value here in America. If any of our members choose to petition legislators against further spending on education, building, or any other phase of government and has his reasons, he is a free agent. His personal stand is not necessarily that of the association.

I must deny, publicly and categorically, in the strongest possible terms, that the Utah Association for the Deaf had anything to do with the student strike at the school last fall. The strike was spontaneous – a reaction of the students against conditions, restrictions, and personalities, which they felt, had become intolerable. The State Board of Education investigated and failed to turn up any connection between the students and the UAD. Severe pressures brought to bear on student leaders also failed to establish any connection. There was one coincidence: A member of our association happened to be at the school on a business matter (verifiable) and out of this coincidence some rather wild rumors grew.

I honestly believe that the adult deaf and parents of deaf children should work together closely toward the better education of deaf children. Working at cross-purposes merely ensures continuing and futile disputes.

Sincerely yours,

Robert G. Sanderson

President

(Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963, p. 14)

Thank you very much for your letter of April 25. As you requested, we shall publish it in full, verbatim.

The UAD welcomes expressions of opinions from parents, teachers, professional educators, and individuals of every philosophy. The pages of the UAD Bulletin are always open to those who wish to be heard.

Membership in the Association entitles one to attend meetings, propose and discuss policies and actions. Where a majority of the membership does not agree with the policies and actions of the officers, they may exercise the American right of “voting them out” at regularly scheduled elections. We would welcome your attendance at our forthcoming convention and would give you and any other parent an opportunity to be heard at the proper time and in proper order; the same privileges are extended to all registered members.

Contrary to the belief of oralists that the adult deaf oppose oral instruction, we certainly do not. It has its place in the curriculum, for those who can benefit from it, along with reading, writing, arithmetic, history, geography, science, and all of the other subjects a school must teach. What the adult deaf do oppose is disproportionate attention to speech and lip-reading aspects, to the extent that the assimilation of subject matter becomes so difficult and so delayed that the total education of the deaf child suffers.

We adult deaf are interested in seeing deaf children acquire the best possible education as well as seeing them learn to speak. As we have learned in our personal lives, covering in the aggregate hundreds of years of experience in coping with the multitudinous socio-economic problems of deafness on a day-to-day basis, speech and lip-reading, while useful, solve no basic problems. The quality and the amount of education received, academically and vocationally, are what count.

I sincerely hope that your deaf son can profit by total oralism. Some children can and some cannot and any professional educator, if he is honest, will tell you so. If it should become apparent to you that your boy’s progress is not what it should be or what you expect or that his happiness (which is so close to your heart) is at stake, then perhaps your love for him would suggest another approach – one that guarantees to him an immediate means of expressing himself. The satisfaction of early and full self expression cannot be overestimated in its value to a well-adjusted child.

It should be remembered that we deaf adults had parents, many of whom once felt as you do, so we understand and appreciate your position.

Where the official position of the Association is concerned, I would suggest that you ascertain the facts with reference to other matters you mention in your letter. However, any member of our association, regardless of his office, may act individually as his conscience so dictates since he is also a taxpayer with those certain rights and privileges we value here in America. If any of our members choose to petition legislators against further spending on education, building, or any other phase of government and has his reasons, he is a free agent. His personal stand is not necessarily that of the association.

I must deny, publicly and categorically, in the strongest possible terms, that the Utah Association for the Deaf had anything to do with the student strike at the school last fall. The strike was spontaneous – a reaction of the students against conditions, restrictions, and personalities, which they felt, had become intolerable. The State Board of Education investigated and failed to turn up any connection between the students and the UAD. Severe pressures brought to bear on student leaders also failed to establish any connection. There was one coincidence: A member of our association happened to be at the school on a business matter (verifiable) and out of this coincidence some rather wild rumors grew.

I honestly believe that the adult deaf and parents of deaf children should work together closely toward the better education of deaf children. Working at cross-purposes merely ensures continuing and futile disputes.

Sincerely yours,

Robert G. Sanderson

President

(Sanderson, The UAD Bulletin, Summer 1963, p. 14)

The Utah Deaf Education

Core Group Is Formed

Core Group Is Formed

In August 2009, the Utah Deaf community was concerned that Steven W. Noyce, a long-time teacher and director of the Utah School for the Deaf, would seek to carry on Dr. Bitter's legacy, jeopardizing the ASL/English bilingual program they had worked so hard to establish when the Utah State Board of Education elected him superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind in 2009. The state board disregarded the Utah Deaf community's outcry.

Steven Noyce was no stranger to the Utah Deaf community, having graduated from the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah between 1965 and 1972 (LinkedIn: Steven Noyce). We were concerned about his advocacy for oral education. In response, Ella Mae Lentz, a co-founder of the Deafhood Foundation and a vocal champion for deaf education, proposed founding the Deaf Education Core Group in April 2010. The group aimed to protect ASL/English bilingual education and fight inequality in the deaf education system. More information about the Utah Deaf Education Core Group is available on the "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream" webpage.

Steven Noyce was no stranger to the Utah Deaf community, having graduated from the Teacher Training Program at the University of Utah between 1965 and 1972 (LinkedIn: Steven Noyce). We were concerned about his advocacy for oral education. In response, Ella Mae Lentz, a co-founder of the Deafhood Foundation and a vocal champion for deaf education, proposed founding the Deaf Education Core Group in April 2010. The group aimed to protect ASL/English bilingual education and fight inequality in the deaf education system. More information about the Utah Deaf Education Core Group is available on the "Dr. Robert G. Sanderson's Dream" webpage.

Utah Deaf Education Core Group's Response to the

Comments Section of the Salt Lake Tribune Article

Comments Section of the Salt Lake Tribune Article

On May 5, 2011, an article in The Salt Lake Tribune titled "Parents rally to get boss of schools for Deaf, blind ousted" ignited a heated debate between ASL/English Bilingual and Listening and Spoken Language advocates. USDB Superintendent Steven W. Noyce misrepresented the intentions of ASL campaigners by suggesting that their goal was to advocate for teaching ASL to all children with hearing loss, a position he could not support. This upset LSL parents, leading to a conflict with the Utah Deaf Education Core Group.

The parents who use LSL supported Steven Noyce's efforts as USDB superintendent. They were concerned that the Deaf community in Utah would attempt to revoke their right to use LSL. The Utah Deaf Education Core Group faced criticism for portraying the issue as a "war" between ASL and LSL. Additionally, LSL parents defended Superintendent Noyce, blaming the 3% districts, the USDB Financial Director, and the State Board for USDB's debt, even though the 3% rule was in place before Noyce's hiring.

According to a newspaper article dated May 5, 2011, the Utah Deaf community wanted to force Deaf or hard of hearing children to use sign language. Not on Core Group's website or blog did ASL parents and members ask to eliminate the LSL program or call LSL parents' names. The Core Group knew they slandered Noyce but did not call him names.

LSL Blog condemned the Utah Deaf Education Core Group. USDB Superintendent Noyce met with LSL parents just before a USBE meeting on May 5, but no evidence exists. Superintendent Noyce apparently was "feeding" the LSL parents false information, making it look like the Utah Deaf Education Core Group wanted the LSL option eliminated, as LSL parents frequently complained in the comments section. Most core group members were raised by hearing parents and attended public schools. Some grew up with ASL; some did not. Many of them were Deaf parents. As Robert G. Sanderson stated in his 1963 letter to D'On Reese, they felt they had a constitutional right to advocate for Deaf Education in Utah because they lived in the deaf educational system themselves.

The real problem was that Superintendent Noyce did not allow families to choose and fund all USD programs equally. ASL and LSL clashed. Superintendent Noyce's mission should be to equally fund and champion both educational approaches, leaving it to parents and families to decide their child's educational modality without bias or favor. The Core Group also acknowledged that most parents opted for LSL, and they allocated funds based on the highest participation rate. However, they also understood his motivation for choosing one participant over all others.

The parents who use LSL supported Steven Noyce's efforts as USDB superintendent. They were concerned that the Deaf community in Utah would attempt to revoke their right to use LSL. The Utah Deaf Education Core Group faced criticism for portraying the issue as a "war" between ASL and LSL. Additionally, LSL parents defended Superintendent Noyce, blaming the 3% districts, the USDB Financial Director, and the State Board for USDB's debt, even though the 3% rule was in place before Noyce's hiring.

According to a newspaper article dated May 5, 2011, the Utah Deaf community wanted to force Deaf or hard of hearing children to use sign language. Not on Core Group's website or blog did ASL parents and members ask to eliminate the LSL program or call LSL parents' names. The Core Group knew they slandered Noyce but did not call him names.

LSL Blog condemned the Utah Deaf Education Core Group. USDB Superintendent Noyce met with LSL parents just before a USBE meeting on May 5, but no evidence exists. Superintendent Noyce apparently was "feeding" the LSL parents false information, making it look like the Utah Deaf Education Core Group wanted the LSL option eliminated, as LSL parents frequently complained in the comments section. Most core group members were raised by hearing parents and attended public schools. Some grew up with ASL; some did not. Many of them were Deaf parents. As Robert G. Sanderson stated in his 1963 letter to D'On Reese, they felt they had a constitutional right to advocate for Deaf Education in Utah because they lived in the deaf educational system themselves.

The real problem was that Superintendent Noyce did not allow families to choose and fund all USD programs equally. ASL and LSL clashed. Superintendent Noyce's mission should be to equally fund and champion both educational approaches, leaving it to parents and families to decide their child's educational modality without bias or favor. The Core Group also acknowledged that most parents opted for LSL, and they allocated funds based on the highest participation rate. However, they also understood his motivation for choosing one participant over all others.

Michelle4LSL, a Listening and Spoken

Language Advocate, Criticizes the American

Sign Language Community

Language Advocate, Criticizes the American

Sign Language Community

One of Michelle4LSL's comments found below the article, "Parents rally to get boss of schools for deaf, blind ousted," addressed the misinformation between ASL and LSL advocates. It is not just a coincidence, but a testament to the enduring nature of this debate, that we see the parallel language between Michelle4LSL (2011) and D'On Reese (1963) attacking the ASL community. Take a look at Michelle4LS's comment in the section below.

To All The ASL or ASL/E

What you all don't seem to get, is that the Utah School Board of Education is FED UP WITH YOU!! They are so tired of your constant complaining. Before Total Communication or TC was taken away, you had battles for other things, it really doesn't matter what is done in your behalf...they give you stuff to shut you up! But you just keep coming back with your hands and mouths open... someone, I don't know who...coined the term Fat Kids for your group....for the very simple reason that no matter how much you are given, you are NEVER satisfied!

Because of all the tirades and rallies and exhaustive amount of tantrums the ASL (not all of you...) community has put the school board through, they have been discussing for months any possible actions they can take to get rid of you as well as the other groups like the blind and LSL. They are so tired of it all that they will do just about anything to pawn us all of on someone else.

In pawning us all off, they will effectively take the rights and services of all the children away. They wrongly assume that our students can get interpreters, speech therapists, (any and all of the Related Services), etc. through the school districts who will have to pick up the slack. First off, the school districts are not equipped to help us...none of us, like we need. Second, for those parents who are ill informed or who are shy and don't have the strength to stand up for their child's rights...they will be left in the dust.

Many of us LSL parents are getting involved and are upset with the ASL group because you are endangering our children's future whether you believe it or not. You can say that the school board cannot do those things, but if you personally talk to members of the board and they are honest with you, they will tell you. The other reason we are involved is because we now understand how much you are all getting, and how little the rest of the kids are getting.

We are not fighting just for our kids...we are fighting for the blind kids. Other than a select few, we have not seen parents from the blind come forth to really fight (for whatever reason that may be...we are not picking on them here, we want to do what we can to help).

We feel that we should all be able to get along...the meanness comes out when your group is essentially screwing the rest of us over because you cannot get enough. We don't believe in your way of teaching, and that is our right...our decision, leave it alone. We have left you alone to do what you want in teaching, don't try to take our rights away.

If you really need or want something, try going back to being a charter school or try asking in a different manner...quit being bullies! Michelle4LSL

What you all don't seem to get, is that the Utah School Board of Education is FED UP WITH YOU!! They are so tired of your constant complaining. Before Total Communication or TC was taken away, you had battles for other things, it really doesn't matter what is done in your behalf...they give you stuff to shut you up! But you just keep coming back with your hands and mouths open... someone, I don't know who...coined the term Fat Kids for your group....for the very simple reason that no matter how much you are given, you are NEVER satisfied!

Because of all the tirades and rallies and exhaustive amount of tantrums the ASL (not all of you...) community has put the school board through, they have been discussing for months any possible actions they can take to get rid of you as well as the other groups like the blind and LSL. They are so tired of it all that they will do just about anything to pawn us all of on someone else.

In pawning us all off, they will effectively take the rights and services of all the children away. They wrongly assume that our students can get interpreters, speech therapists, (any and all of the Related Services), etc. through the school districts who will have to pick up the slack. First off, the school districts are not equipped to help us...none of us, like we need. Second, for those parents who are ill informed or who are shy and don't have the strength to stand up for their child's rights...they will be left in the dust.

Many of us LSL parents are getting involved and are upset with the ASL group because you are endangering our children's future whether you believe it or not. You can say that the school board cannot do those things, but if you personally talk to members of the board and they are honest with you, they will tell you. The other reason we are involved is because we now understand how much you are all getting, and how little the rest of the kids are getting.

We are not fighting just for our kids...we are fighting for the blind kids. Other than a select few, we have not seen parents from the blind come forth to really fight (for whatever reason that may be...we are not picking on them here, we want to do what we can to help).

We feel that we should all be able to get along...the meanness comes out when your group is essentially screwing the rest of us over because you cannot get enough. We don't believe in your way of teaching, and that is our right...our decision, leave it alone. We have left you alone to do what you want in teaching, don't try to take our rights away.

If you really need or want something, try going back to being a charter school or try asking in a different manner...quit being bullies! Michelle4LSL

The Utah Deaf Education Core Group

Responds to Michelle4LSL's & Other Comments

Responds to Michelle4LSL's & Other Comments

In response to Michelle4LSL's and other comments posted by the Listening & Spoken Language advocate in the comment section of the Salt Lake Tribune's "Parents rally to get boss of schools for deaf, blind ousted" article on May 5, 2011, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group, like former Utah Association for the Deaf President Robert G. Sanderson in the 1960s, clarified their objectives and intentions regarding USDB Superintendent Noyce, as shown in the section below. This swiftly ended the debate between the two groups. The Utah Deaf Education Core Group also posted it on their website, as shown below.

We are NOT fighting to get LSL removed from the Deaf division of USDB. We respect parents' right to choose LSL if they feel that it would work for their children. This is NOT an ASL versus LSL battle. We have never said that our goal was to have USD be an ASL-only school. We only ask for fair, unbiased options for all families and students, and for families to be able to choose both options if they so desire.

Let it be known that in 2007, elementary teachers in the Central Deaf Division of USDB who taught in the Total Communication program asked to be merged with JMS. Later, in 2009, when Steven W. Noyce revamped Parent Infant Program, he removed what was called the Total Communication option (which included both sign and speech) and restructured the program so that it offers either LSL or ASL, which upset many parents who wanted both options. Mr. Noyce also announced the phasing out of the USDB Total Communication program at Churchill. The Deaf community had no part of this change.

The Total Communication program utilized signing and speaking simultaneously and was ineffective for a number of reasons, one of which is that ASL and English are two distinct languages. Advocates of ASL/English bilingualism support the utilization of both ASL and written/spoken English in the instruction of deaf and hard of hearing children, with the understanding that one or the other language is used as appropriate and not simultaneously. A thorough explanation of this, however, is beyond the scope of this report.