UTAH DEAF HISTORY

The website is currently undergoing construction. Please come back later for updates.

"Yesterday is history.

Tomorrow is a mystery.

Today is a gift, that's why they call it the present." ~Eleanor Roosevelt~

Tomorrow is a mystery.

Today is a gift, that's why they call it the present." ~Eleanor Roosevelt~

Welcome to our Utah Deaf History and Culture website! I'm excited to have you join us as we explore the rich history that may have gone unnoticed statewide and nationwide. On October 21, 2012, I launched the 'Utah Deaf History and Culture' website, a crucial platform for preserving this exceptional legacy. Without your commitment to learning and our dedication to historic preservation, the Utah Deaf History Collection, which includes photographs, films, and historical documents, could have lost significant events and cultural heritage spanning decades. I have been researching, collecting, and writing about Utah Deaf History since 2006, and I am honored to share this journey with you.

Utah has several historical highlights,

including the following:

including the following:

Gallaudet University

On June 8, 1897, Elizabeth DeLong and John H. Clark, cousins who became deaf from medical conditions that were common back then, graduated from the Utah School for the Deaf. That year, they were the only two graduates, and they were the first students from Utah to attend Gallaudet College, which was founded in Washington, DC, in 1864 and serves Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled students. They thrived at Gallaudet, where they served as editors for The Buff and Blue, the college's student newspaper. Elizabeth's perseverance paid off in 1901 during her senior year when she was elected to serve as president of Gallaudet College's O.W.L.S., a secret society for women at Gallaudet College, now known as Phi Kappa Zeta. This society provided a safe space to debate, study poetry and literature, and form sisterhood bonds in a largely male environment on the Gallaudet campus. Elizabeth and John both graduated in 1902 and went on to have a successful profession, demonstrating their resilience and determination.

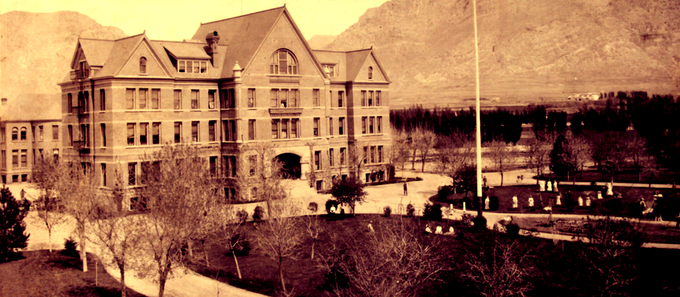

Utah School for the Deaf

The Utah School for the Deaf was established in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1884. However, unlike other state schools for the deaf, the school moved several times in the Salt Lake area before settling in Ogden in 1896, when Utah became a state. Since then, the Utah School for the Deaf has faced a long-standing debate on whether to teach using the oral or sign language method until the 1960s, when oral became more emphasized under the leadership of Dr. Grant B. Bitter, a renowned oral and mainstream education advocate. Utah's movement to mainstream all Deaf children had a significant impact, earning him the title of 'Father of Mainstreaming.' Dr. Bitter, a parent of a Deaf daughter and professor at the University of Utah teaching the Oral Teacher Training Program, championed mainstreaming for all Deaf children, leading to its widespread acceptance in 1975 with the passage of Public Law 94-142, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Dr. Bitter's advocacy for the oral and mainstreaming movements sparked a long-standing feud with the Utah Association for the Deaf, a group comprised mainly of graduates from the Utah School for the Deaf, particularly Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a prominent Deaf community leader in Utah who became deaf at the age of 11 and was a staunch supporter of sign language and state schools for the deaf. The intense animosity between these two giants was due to the ongoing dispute over oral and sign language in Utah's deaf educational system. Their struggle was akin to a chess game, with each maneuvering politically to gain the upper hand in the deaf educational system. The Utah Association for the Deaf demonstrated remarkable resilience when faced with Dr. Bitter's challenges, marking a significant turning point in our history.

In 1962, the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, introduced the dual-track program, commonly known as the "Y" system, which had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children. This system divided learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling. Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement. The 'Y' system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. This preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department. Unfortunately, the placement of the transferred students in the signing program already branded them as 'oral failures.' The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The shift in focus and the hiring of more oral teachers had a significant impact on the school's learning environment, altering its dynamics and atmosphere.

Utah also took a different approach to deaf education compared to other states, where residential schools were the norm. Instead of having children attend school on campus, Utah prioritized mainstreaming. In 1959, the Utah School for the Deaf established its Extension Division in Salt Lake City, Utah, to promote mainstreaming. Throughout the 1960s, the movement grew steadily in school districts. Since then, with the support of parents who advocated for oral education and integration into mainstream schools, the school has been a leader in mainstreaming students who are deaf or hard of hearing into local school districts all over Utah. This collective effort, along with Dr. Bitter's mission, spearheaded the mainstreaming movement and led to a significant shift in deaf education.

For nearly a decade, the Utah Association for the Deaf, in collaboration with the Parent-Teacher-Student Association, comprised supportive parents who advocated for sign language and fought against the "Y" system. However, the authorities dismissed their voices, especially after the 1962 student protests over the social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus. Another round of students' acts of resistance during the 1969 walkout protest against the continued enforcement of "Y" social segregation in the dual-track program was a defining moment in history, echoing the 1962 student protest at the Utah School for the Deaf. Following the 1969 protest and internal demonstrates of the oral and sign language students against social segregation, Ned C. Wheeler, a 1933 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf who became deaf at the age of 13 and served as chair of the Governor's Advisory Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, proposed the two-track program to eliminate the "Y" system. This new program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child, aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education. In 1970, the Utah State Board of Education approved this policy under the guidance of Dr. Jay J. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a sign language interpreter and Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, who came up with the two-track program idea and was a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community.

However, the mental trend of the 'Y' system in the two-track program, with prevalent oral bias, persisted. This biased information had a profound impact, limiting the choices parents could make for their Deaf children's education and communication. Although Dr. J. Jay Campbell tried to provide fair information in the 1970s, Dr. Bitter opposed his efforts because he believed that total communication was a concept, not a word, and also a philosophy, not a method. In 2010, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group challenged this biased approach and advocated for unbiased and equal information. Superintendent Steven W. Noyce of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, an oral advocate and former university student of Dr. Bitter, as well as a long-time teacher and school director, created the Parent Infant Program Orientation to provide parents with fair and balanced information. However, parents still had to choose an "either/or" selection between ASL/English bilingual (replaced total communication) or listening and spoken language (replace oral) options for their children's education and communication, which resulted in the expansion of the listening and spoken program because the majority of Deaf children are born to hearing parents.

In 1998, the Utah State Board of Education approved the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf as one of the state's first two charter schools. Co-founded by Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, born to a well-known Wilding Deaf family, a highly respected figure in the Deaf community and Deaf parent of three Deaf children, and Jeff Allen, a hearing parent of a Deaf daughter, the Jean Massieu School for the Deaf began operating as a public charter school in 1999.

Before the merger, the Utah School for the Deaf hesitated to include the ASL/English bilingual program. In 2005, after Joe Zeidner's legislative efforts, the Utah Legislature and the Utah State Board of Education, in a collaborative effort, approved the merger of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf with the Utah School for the Deaf. This merger brought about a significant change, offering parents and students a new ASL/English bilingual option. The 2009 amendment to the Utah Code that regulated the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind since the late 1970s also discontinued the promotion of mainstreaming, signaling a shift towards a more inclusive educational approach. The goal was to increase the number of students on the school campus, a step that promised a brighter future for deaf education.

After over fifty years of oral advocacy group dominance, starting in 1962, at the Utah School for the Deaf, Michelle Tanner, Associate Superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf, with the support of Joel Coleman, Superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, achieved a significant milestone in 2016 by introducing the hybrid program, demonstrating significant progress. The hybrid program allows the ASL/English bilingual program (replaced total communication) and the listening and spoken language (replaced oral) program to work together without bias, providing Deaf students with a more personalized educational placement. This program also eliminates the need for parents to make an 'either/or' choice between the two programs, a significant step towards providing unbiased and equal information and marking a significant milestone in pursuing an equal educational system for Deaf students in a more inclusive educational system.

Today, the bilingual deaf schools, under the Utah School for the Deaf umbrella, are named after three prominent Deaf individuals: Kenneth C. Burdett of the Deaf (Ogden), Jean Massiue School for the Deaf (Salt Lake City), and Elizabeth DeLong (Springville).

In 1962, the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah, introduced the dual-track program, commonly known as the "Y" system, which had a profound impact on the education of Deaf children. This system divided learning into two distinct channels: the oral department, which focused on speech, lipreading, amplified sound, and reading, and the simultaneous communication department, which emphasized instruction through the manual alphabet, signs, speech, and reading. Initially, all Deaf children were required to enroll in the oral program for the first six years of their schooling. Following this period, a committee would assess each child's progress and determine their placement. The 'Y' system favored the oral mechanism over the sign language approach, limiting families' choices in the school system. This preference for the oral mechanism was based on the belief that speech was crucial for Deaf children's integration into the hearing world. Parents and Deaf students did not have the freedom to choose the program until the child entered 6th or 7th grade, at which point they could either continue in the oral department or transition to the simultaneous communication department. Unfortunately, the placement of the transferred students in the signing program already branded them as 'oral failures.' The dual-track program also divided Ogden's residential campus into an oral department and a simultaneous communication department, each with its own classrooms, dining halls, dormitory facilities, recess periods, and extracurricular activities. The shift in focus and the hiring of more oral teachers had a significant impact on the school's learning environment, altering its dynamics and atmosphere.

Utah also took a different approach to deaf education compared to other states, where residential schools were the norm. Instead of having children attend school on campus, Utah prioritized mainstreaming. In 1959, the Utah School for the Deaf established its Extension Division in Salt Lake City, Utah, to promote mainstreaming. Throughout the 1960s, the movement grew steadily in school districts. Since then, with the support of parents who advocated for oral education and integration into mainstream schools, the school has been a leader in mainstreaming students who are deaf or hard of hearing into local school districts all over Utah. This collective effort, along with Dr. Bitter's mission, spearheaded the mainstreaming movement and led to a significant shift in deaf education.

For nearly a decade, the Utah Association for the Deaf, in collaboration with the Parent-Teacher-Student Association, comprised supportive parents who advocated for sign language and fought against the "Y" system. However, the authorities dismissed their voices, especially after the 1962 student protests over the social segregation between oral and sign language students on Ogden's residential campus. Another round of students' acts of resistance during the 1969 walkout protest against the continued enforcement of "Y" social segregation in the dual-track program was a defining moment in history, echoing the 1962 student protest at the Utah School for the Deaf. Following the 1969 protest and internal demonstrates of the oral and sign language students against social segregation, Ned C. Wheeler, a 1933 graduate of the Utah School for the Deaf who became deaf at the age of 13 and served as chair of the Governor's Advisory Council of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, proposed the two-track program to eliminate the "Y" system. This new program allowed parents to choose between oral and total communication methods of instruction for their deaf child, aged between 2 1/2 and 21, marking a significant shift in deaf education. In 1970, the Utah State Board of Education approved this policy under the guidance of Dr. Jay J. Campbell, the husband of Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a sign language interpreter and Deputy Superintendent of the Utah State Office of Education, who came up with the two-track program idea and was a crucial ally of the Utah Deaf community.

However, the mental trend of the 'Y' system in the two-track program, with prevalent oral bias, persisted. This biased information had a profound impact, limiting the choices parents could make for their Deaf children's education and communication. Although Dr. J. Jay Campbell tried to provide fair information in the 1970s, Dr. Bitter opposed his efforts because he believed that total communication was a concept, not a word, and also a philosophy, not a method. In 2010, the Utah Deaf Education Core Group challenged this biased approach and advocated for unbiased and equal information. Superintendent Steven W. Noyce of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, an oral advocate and former university student of Dr. Bitter, as well as a long-time teacher and school director, created the Parent Infant Program Orientation to provide parents with fair and balanced information. However, parents still had to choose an "either/or" selection between ASL/English bilingual (replaced total communication) or listening and spoken language (replace oral) options for their children's education and communication, which resulted in the expansion of the listening and spoken program because the majority of Deaf children are born to hearing parents.

In 1998, the Utah State Board of Education approved the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf as one of the state's first two charter schools. Co-founded by Minnie Mae Wilding-Diaz, born to a well-known Wilding Deaf family, a highly respected figure in the Deaf community and Deaf parent of three Deaf children, and Jeff Allen, a hearing parent of a Deaf daughter, the Jean Massieu School for the Deaf began operating as a public charter school in 1999.

Before the merger, the Utah School for the Deaf hesitated to include the ASL/English bilingual program. In 2005, after Joe Zeidner's legislative efforts, the Utah Legislature and the Utah State Board of Education, in a collaborative effort, approved the merger of the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf with the Utah School for the Deaf. This merger brought about a significant change, offering parents and students a new ASL/English bilingual option. The 2009 amendment to the Utah Code that regulated the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind since the late 1970s also discontinued the promotion of mainstreaming, signaling a shift towards a more inclusive educational approach. The goal was to increase the number of students on the school campus, a step that promised a brighter future for deaf education.

After over fifty years of oral advocacy group dominance, starting in 1962, at the Utah School for the Deaf, Michelle Tanner, Associate Superintendent of the Utah School for the Deaf, with the support of Joel Coleman, Superintendent of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, achieved a significant milestone in 2016 by introducing the hybrid program, demonstrating significant progress. The hybrid program allows the ASL/English bilingual program (replaced total communication) and the listening and spoken language (replaced oral) program to work together without bias, providing Deaf students with a more personalized educational placement. This program also eliminates the need for parents to make an 'either/or' choice between the two programs, a significant step towards providing unbiased and equal information and marking a significant milestone in pursuing an equal educational system for Deaf students in a more inclusive educational system.

Today, the bilingual deaf schools, under the Utah School for the Deaf umbrella, are named after three prominent Deaf individuals: Kenneth C. Burdett of the Deaf (Ogden), Jean Massiue School for the Deaf (Salt Lake City), and Elizabeth DeLong (Springville).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

To support the Deaf members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, they formed a Sunday School class in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1891. Laron Pratt, the son of the late Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Apostle Orson Pratt and a pioneering leader of the Utah Deaf community, taught the class. In 1896, the Utah School for the Deaf relocated to Ogden, Utah, forming another class for those members taught by Max W. Woodbury, a teacher and principal of the Utah School for the Deaf.

Established in 1917, the Ogden Branch for the Deaf served as a beacon for those Deaf members who had connections to the Utah School for the Deaf or lived in Ogden, Utah, under the leadership of Max W. Woodbury, the branch president for 51 years, and Elsie M. Christiansen, a houseparent of the Utah School for the Deaf and the branch clerk for 28 years. Max and Elsie played a significant role in building the first chapel for the Deaf members, and their unwavering commitment and collaboration with church authorities were instrumental in overseeing the construction process. Since the branch's founding in 1917, Ecclesiastical Leader Max W. Woodbury has paved the way for future branches and valleys for the deaf. The branch's closure in 1999 due to accessibility concerns was a significant loss to the community.

Lloyd H. Perkins, a carpenter, branch president, and bishop of the Salt Lake Valley for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, showed remarkable perseverance in creating a 'deaf space' that would meet the visual needs of members. His determination ultimately led to the approval of his proposal despite its initial rejection. Lloyd guided the construction of a deaf-friendly Salt Lake Valley Ward chapel in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1977, which is still in operation today. Deaf members were also involved in the design process, guiding the creation of both churches while keeping their visual accessibility needs in mind, which was a significant accomplishment for the Utah Deaf community.

Established in 1917, the Ogden Branch for the Deaf served as a beacon for those Deaf members who had connections to the Utah School for the Deaf or lived in Ogden, Utah, under the leadership of Max W. Woodbury, the branch president for 51 years, and Elsie M. Christiansen, a houseparent of the Utah School for the Deaf and the branch clerk for 28 years. Max and Elsie played a significant role in building the first chapel for the Deaf members, and their unwavering commitment and collaboration with church authorities were instrumental in overseeing the construction process. Since the branch's founding in 1917, Ecclesiastical Leader Max W. Woodbury has paved the way for future branches and valleys for the deaf. The branch's closure in 1999 due to accessibility concerns was a significant loss to the community.

Lloyd H. Perkins, a carpenter, branch president, and bishop of the Salt Lake Valley for the Deaf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, showed remarkable perseverance in creating a 'deaf space' that would meet the visual needs of members. His determination ultimately led to the approval of his proposal despite its initial rejection. Lloyd guided the construction of a deaf-friendly Salt Lake Valley Ward chapel in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1977, which is still in operation today. Deaf members were also involved in the design process, guiding the creation of both churches while keeping their visual accessibility needs in mind, which was a significant accomplishment for the Utah Deaf community.

Utah Association of the Deaf

The Utah Association of the Deaf was established in 1909 at the Utah School for the Deaf in Ogden, Utah. Elizabeth DeLong, a Deaf woman who proposed the association's formation, was the first female president, defeating two Deaf male candidates. She was an accomplished woman who served as president of the Utah Association of the Deaf from 1909 to 1915. During her second term as president, she delivered a speech at the UAD Convention in 1915 advocating for women's suffrage. This is significant because the 19th Amendment, which only applied to white women, did not grant women the right to vote for another decade until 1920. During that period, women belonging to the Deaf community could not cast their vote in the National Association of the Deaf elections until 1965. Later in the twentieth century, women of color gained the right to vote. Elizabeth DeLong was also the first Deaf woman in the United States to lead a NAD state chapter association. Notably, in 1870, Utah women made history by being the first women in modern America to exercise their voting rights. Seraph Young Ford, a schoolteacher, became the first woman to cast her vote in the United States on February 14, 1870, which marked a significant milestone in the journey toward women's suffrage. Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, a doctor, further advanced women's suffrage when she became the first female state senator in the United States 26 years later, in 1896. During her time as a legislator and serving on the board of the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind, she sponsored two bills: one to make it mandatory for Deaf and Blind students to attend the Utah Schools for the Deaf and Blind in Ogden, Utah, and the other to establish an infirmary on campus.

In 1965, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 marked a significant milestone in the fight for equality, as it allowed Deaf women to vote and gave Black Deaf individuals the opportunity to join and vote in the National Association of the Deaf. Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, the association's president and a prominent figure locally and nationally, led this historic move. These changes were a significant step towards building a more inclusive community for all Deaf people, regardless of race, gender, and sexuality, as well as a milestone in the NAD's history, marking a step towards inclusivity and equality.

Since establishing the Utah Association of the Deaf in 1909, the Utah Association of the Deaf has been a leading voice, advocating for civil rights across various areas such as auto insurance, traffic safety, telecommunications, interpreters, education, early intervention, employment, rehabilitation, and more. The Utah Association for the Deaf (it was named between 1963 and 2012) was also the driving force behind establishing the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, which is now a thriving hub for community activities. The Utah Association for the Deaf also helped establish the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, a beacon of education for Deaf children. Additionally, they championed expanding interpreting services and establishing Deaf Education at Utah State University, emphasizing ASL/English bilingual (then Total Communication), thereby promoting bilingual education for the deaf.

W. David "Dave" Mortensen, who served on the association, is the longest-serving president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, and no one has beaten his 22-year record. He played a crucial role in advancing civil and accessible rights in the Utah Deaf community. Dave took over where Dr. Sanderson left off and successfully completed the projects until the end. They supported and relied on each other to succeed. Dave could not have advocated for the community without Robert's initial work, and Robert could not have accomplished his work without Dave's support.

In 1963, the Utah Association of the Deaf took a significant step by changing its name from 'of' to 'for,' becoming the Utah Association for the Deaf. Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, the association's president, demonstrated the association's commitment to inclusivity by appointing Beth Ann Stewart Campbell and Gene Stewart, who were Children of Deaf Adults (CODAs), to the board in light of the growing oral and mainstreaming movements. Under the leadership of Philippe Montalette, the association's president, they reversed the change in 2012, marking a significant milestone in the history of deaf advocacy. After realizing that their previous name was patronizing towards the Deaf community, implying that they were second-class citizens who needed help from society, they decided to revert to the Utah Association of the Deaf. They made this change to ensure recognition of the Deaf community, equal treatment, and full participation in society.

Under the leadership of Stephen Persinger, the association's president, the Utah Association of the Deaf lobbied state legislators to pass Utah Code House Bill (HB) 60, which changed the term "hearing impaired" in state law to "deaf and hard of hearing." Utah Governor Gary Hebert signed HB 60 into law on March 17, 2017, making Utah the first state in the United States to achieve this goal. Governor Herbert signed House Bill 60 into law on April 11, 2017.

In 2019, Kim Lucas became the second woman to be president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, breaking a 110-year-long streak of men serving in the role. This is a significant milestone for the organization. Additionally, Kim is the first queer president to lead the Utah Association of the Deaf, making history in more ways than one.

In 1965, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 marked a significant milestone in the fight for equality, as it allowed Deaf women to vote and gave Black Deaf individuals the opportunity to join and vote in the National Association of the Deaf. Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, the association's president and a prominent figure locally and nationally, led this historic move. These changes were a significant step towards building a more inclusive community for all Deaf people, regardless of race, gender, and sexuality, as well as a milestone in the NAD's history, marking a step towards inclusivity and equality.

Since establishing the Utah Association of the Deaf in 1909, the Utah Association of the Deaf has been a leading voice, advocating for civil rights across various areas such as auto insurance, traffic safety, telecommunications, interpreters, education, early intervention, employment, rehabilitation, and more. The Utah Association for the Deaf (it was named between 1963 and 2012) was also the driving force behind establishing the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, which is now a thriving hub for community activities. The Utah Association for the Deaf also helped establish the Jean Massieu School of the Deaf, a beacon of education for Deaf children. Additionally, they championed expanding interpreting services and establishing Deaf Education at Utah State University, emphasizing ASL/English bilingual (then Total Communication), thereby promoting bilingual education for the deaf.

W. David "Dave" Mortensen, who served on the association, is the longest-serving president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, and no one has beaten his 22-year record. He played a crucial role in advancing civil and accessible rights in the Utah Deaf community. Dave took over where Dr. Sanderson left off and successfully completed the projects until the end. They supported and relied on each other to succeed. Dave could not have advocated for the community without Robert's initial work, and Robert could not have accomplished his work without Dave's support.

In 1963, the Utah Association of the Deaf took a significant step by changing its name from 'of' to 'for,' becoming the Utah Association for the Deaf. Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, the association's president, demonstrated the association's commitment to inclusivity by appointing Beth Ann Stewart Campbell and Gene Stewart, who were Children of Deaf Adults (CODAs), to the board in light of the growing oral and mainstreaming movements. Under the leadership of Philippe Montalette, the association's president, they reversed the change in 2012, marking a significant milestone in the history of deaf advocacy. After realizing that their previous name was patronizing towards the Deaf community, implying that they were second-class citizens who needed help from society, they decided to revert to the Utah Association of the Deaf. They made this change to ensure recognition of the Deaf community, equal treatment, and full participation in society.

Under the leadership of Stephen Persinger, the association's president, the Utah Association of the Deaf lobbied state legislators to pass Utah Code House Bill (HB) 60, which changed the term "hearing impaired" in state law to "deaf and hard of hearing." Utah Governor Gary Hebert signed HB 60 into law on March 17, 2017, making Utah the first state in the United States to achieve this goal. Governor Herbert signed House Bill 60 into law on April 11, 2017.

In 2019, Kim Lucas became the second woman to be president of the Utah Association of the Deaf, breaking a 110-year-long streak of men serving in the role. This is a significant milestone for the organization. Additionally, Kim is the first queer president to lead the Utah Association of the Deaf, making history in more ways than one.

Robert G. Sanderson Community Center

of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing

of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing

The Utah Association for the Deaf exhibited remarkable commitment for 40 years, starting in 1962 and ending in 1992, to establish a community center through legislation. Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, Eugene W. Petersen, and G. Leon Curtis, all association members, spearheaded the planning process, and W. David Mortensen completed the project. In 1992, their efforts culminated in the opening of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, a new permanent facility in Taylorsville, Utah. The state dedicated this facility, the first of its kind, to serving the Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled communities.

On October 4, 2003, under the leadership of Marilyn Tiller Call, director, the Utah Deaf community held a renaming ceremony to honor Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a former Deaf Services counselor and director of the community center. The event marked the renaming of the center to the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. This center is the only state-funded Deaf agency in the United States, providing essential accessibility and communication services. The Utah Deaf community actively participated in the construction of the Sanderson Community Center, ensuring that its design met their accessibility needs.

On October 4, 2003, under the leadership of Marilyn Tiller Call, director, the Utah Deaf community held a renaming ceremony to honor Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, a former Deaf Services counselor and director of the community center. The event marked the renaming of the center to the Robert G. Sanderson Community Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. This center is the only state-funded Deaf agency in the United States, providing essential accessibility and communication services. The Utah Deaf community actively participated in the construction of the Sanderson Community Center, ensuring that its design met their accessibility needs.

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf

Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, as the unwavering president of the National Association of the Deaf, spearheaded the expansion of interpreting services in Utah. In 1968, the Utah Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf emerged as the state's first interpreting service for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing communities. They also joined forces with the Utah Association for the Deaf to establish Utah's first interpreter training program and certification procedures. Additionally, Dr. Robert G. Sanderson, then-NAD president and one of the first participants of the newly formed Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf in 1964, inspired Beth Ann Stewart Campbell, a Utah native, Child of Deaf Adults (CODA), and former director of the Utah Community Center for the Deaf, to undertake the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf certification exam. This led to becoming the first nationally RID certified interpreter in Utah and the United States in 1965, a truly remarkable milestone. Moreover, W. David Mortensen, president of the Utah Association for the Deaf, steadfastly led Utah to pass Senate Bills (SB) 41 and 42, focusing on interpreting certification and training and recognizing American Sign Language as a foreign language in secondary and post-secondary schools, respectively. All these efforts significantly improved the lives of the Deaf community in Utah.

Sorenson Communications, Inc.

Sorenson Communications, Inc., a company based in Salt Lake City, Utah, created the first videophone designed for Deaf and hard of hearing individuals in 2003, as envisioned by Jonathan Hudson, a Utah Deaf native. Nowadays, they provide a video relay system that is "functionally equivalent," allowing users to benefit from and enjoy its ease of use.

Utah's Many Firsts

Furthermore, Utah boasts a rich history of notable firsts, and it is essential to acknowledge and remember the significant contributions made by many prominent leaders in the Deaf community. As the sole owner and operator of this website, I am committed to preserving the rich history of the Utah Deaf community.

A BIG LOSS IN DEAF HISTORY

Barry Strassler, the owner of DeafDigest, wrote about a self-taught Deaf historian he met in his article "A Big Loss in Deaf History." Despite not attending college, the historian was always fascinated by the history of the Deaf community. He conducted his studies at Gallaudet University's library and the Library of Congress and recorded his findings in notebooks. He kept several books on Deaf history, as well as his journals, at home. However, he never shared his discoveries with anyone and kept them to himself. He had no close friends or family members, so no one knew about this enormous treasure when he passed away. "A horrible waste in Deaf history," remarked Barry Strassler, DeafDigest Editor, on November 18, 2012.

Given Utah's changing demographics, it would be unfortunate if the state's Deaf heritage were lost. Thanks to digitization, anyone can now access the rich history of the Utah Deaf community for historical preservation, genealogy, and research. Virginia C. Borggaard, the author of Celebrating A Rich Heritage 1901–2001, states, "Utah has always been a forerunner in promoting the history of the state's Deaf community." For this reason, we are committed to keeping up with and preserving Utah's Deaf history.

Thank you for visiting our website; we hope you find it entertaining and informative!

Cheers!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Given Utah's changing demographics, it would be unfortunate if the state's Deaf heritage were lost. Thanks to digitization, anyone can now access the rich history of the Utah Deaf community for historical preservation, genealogy, and research. Virginia C. Borggaard, the author of Celebrating A Rich Heritage 1901–2001, states, "Utah has always been a forerunner in promoting the history of the state's Deaf community." For this reason, we are committed to keeping up with and preserving Utah's Deaf history.

Thank you for visiting our website; we hope you find it entertaining and informative!

Cheers!

Jodi Becker Kinner

Copyright © Jodi Becker Kinner, 2012 - 2024. All rights reserved. No part of this website may be reproduced or published without the express consent of the author. If you have additional information about Utah Deaf history, or photos/materials that you would like share, please contact Jodi Becker Kinner via email at jodibeckerkinner@gmail.com